I have trouble reaching Mexican sculptor Tania Pérez Córdova as her phone isn’t updating with new emails. It’s ironic because this glitch could almost have been (but wasn’t) a function of a sculpture from her Things in Pause series, which interrupt the flow of people’s existence. Her 2013 work Call Forwarding, for instance, comprised a porcelain slab embedded with a SIM card; while the piece was exhibited, the owner of the card had to arrange for calls to be forwarded to a new card. Pérez Córdova layers different technologies, time periods and materials—gunpowder, cigarette ash, makeup, foam, bronze poured into sand, jewellery—to present poetic snapshots of a narrative that has already happened or might yet take place. Her elegant sculptures are questions hanging in the air, a feeling unarticulated.

In her intimate creations, vestiges of human presence can be discerned as objects are given new purposes; a medallion of melted beer cans trapped between reused window glass, a bronze cast of someone’s pocket, a coloured contact lens on marble. She often activates her sculptures through a playfully performative element such as having a person in the gallery wear the partner contact lens or earring to one in a sculpture. Driven by a fascination with materiality, her recent body of work for her solo show at Kunsthalle Basel last October explored the slippage between original and copy, juxtaposing everyday items like a chain-link fence and a copper saucepan with their hand-cast replicas.

- We Focus on a Woman Facing Sideways, 2013–17. Bronze, Swarovski Crystal Drop earring, and a woman wearing the other earring

Pérez Córdova studied at the Mexican art school Esmeralda and then at Goldsmiths in London. Since then her star has steadily risen. She took part in the 2015 New Museum Triennial in New York, had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 2017 and will take part in the Aichi Triennale, Japan, this year. We finally caught up in a cafe in the leafy Condesa district and discussed her practice, the Basel show and gender equality in notoriously macho Mexico.

Time seems to be an intrinsic element of your work.

I like to think of sculptures as events, as a thing that happens either by the way something is made or by the way it exists when displayed. So this always has a relationship with a temporality, a beginning and an end, a narrative. For my Things in Pause series I thought I would make sculptures that by existing would make a pause elsewhere. The most obvious example was the SIM card. I would borrow someone’s telephone, the phone would be suspended for the show and the SIM card would later be returned. I had the idea that by seeing these sculptures you would almost imagine a cinematic image of another situation that has stopped for this one to exist. But then technology changed so fast and the first sculptures had these big SIM cards, so that sculpture feels like it aged really quickly and was implying other things, like that the person who lent this card could not afford the latest phone.

Your sculptures feel like artefacts of our age, offering fragmentary clues to future civilizations about our lives and rituals, such as smoking or wearing contact lenses.

As you say this I’m thinking it’s almost as if the objects in that series were left over from a human action, like the remains of a human presence.

It’s funny because some time ago I found out there’s this process called “accelerated ageing” and companies test different materials to see how they will age in the future. They have machines that really are like time machines that recreate weather conditions. I aged this black fabric for my piece How to Use Reversed Psychology with Pictures (2012/13) and it’s like a fast-forwarded object. We are in this present time but this object is now effectively in the future.

You seem to personify objects or give them some agency.

I always liked to think that objects were more than objects, they also included a person or an action or a movement. They’re there like an active object to set up an event or they’re the memory of one. Maybe it’s a nostalgia for it to be something else than a sculpture, and at the same time I consider myself very much a sculptor.

“We are in this present time but this object is now effectively in the future”

How important is language in your work? In contrast with the minimal aesthetic of the sculptures, your captions include enormous detail such as “glass from a window facing south”, while titles sometimes feel like clauses.

I think a lot about the way things are described. For instance, with my caption “bronze, Swarovski crystal drop earring, and a woman wearing the other earring”, it’s as if the description of the materials goes beyond materiality to the condition of something. With the title of that work We Focus on a Woman Facing Sideways, I was reading a film script and that was a note describing things the camera would focus on. I liked the idea that while seeing the sculpture you’d think of the woman wearing the other earring rather than just seeing the sculpture.

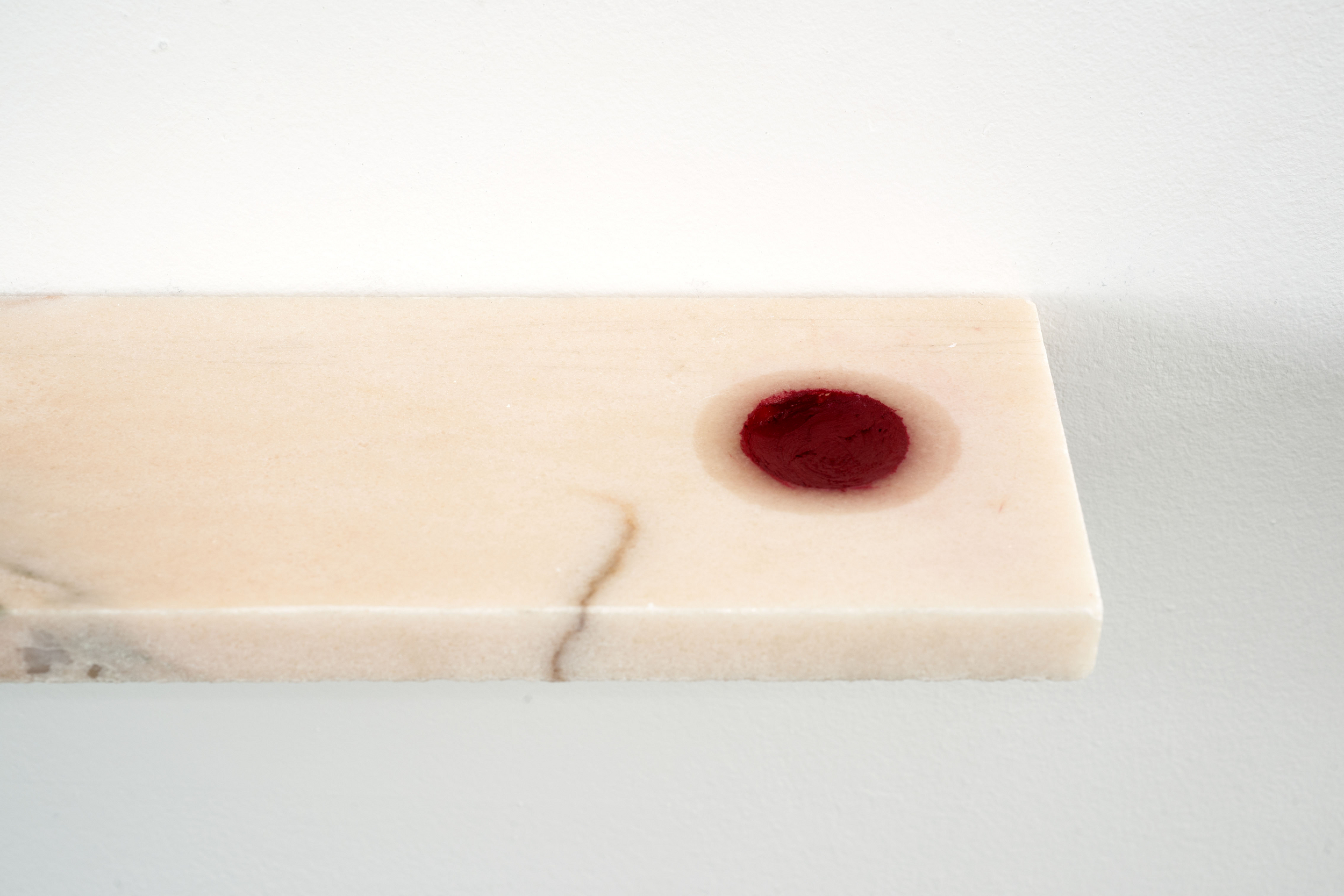

Something Separated by Commas, 2014. Marble, green contact lens, red lipstick

Do your works start with the idea?

I feel like there’s two things happening at the same time. First, I’m truly just interested in the material or the way something is made. I’m physically involved in the making of all my works and that’s important to me. And secondly, I usually have this completely abstract idea of what I would like, almost like a feeling, an echo of a situation. I never sketch because I never have an idea formally of how I would like it to look and then fight for it. The final shape of things is always quite accidental on purpose. It’s as if I need to find a point of view to describe something and then I can call it a work.

Your sculptures have an intimacy that is perhaps absent from the work of the previous generation.

I would not like my work to be seen as biographical but I think it’s to do with a more personal process. I was trying to honestly think what feels more like my personal reality in terms of materials or references. I never felt the need for my works to look Mexican because the artists I’m interested in aren’t representations of cultures or movements, it’s their individuality that interests me.

“The art world here is completely run by men. There’s a handful of women in power and I’m not sure how committed to the cause they are, or if they’re enablers of dynamics of male power”

- Installation view, Daylength of a Room, Kunsthalle Basel, 2018. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

How is it being a female artist here?

In some way you could say it’s a privilege because we’re not that many. But culturally Mexico is very behind in terms of gender equality. Really, really behind. There’s not a lot of politics of gender equality in jobs or even the way people are educated. The art world here is completely run by men. There’s a handful of women in power and I’m not sure how committed to the cause they are, or if they’re enablers of dynamics of male power. It’s always uncomfortable to bring it into the conversation, with men and women.

Your Kunsthalle Basel show Daylength of a Room returned to the theme of time, featuring an installation of a plant with a degenerative disease and sculptures made of lava and of baked bread. Why did you choose that title and what exactly is a “daylength”?

It’s a word used in biology to talk about Circadian rhythms of plants and animals. The idea is that a single day has different lengths for different living beings and I wanted to give each individual sculpture a unique presence in time. For example, a work in the show called Woman Next to a Still-Life was inspired by encountering a note in the Egyptian Museum of Turin describing how sculptures and sphinx were reused by subsequent dynasties, who slightly altered the facial expressions of the carvings when they ruled.

I love the idea of a stone as transformative and also to think that it points toward its own future rather than its past. The form is rather unstable like other pieces in the show, as if it’s about their potential change, not their present form.