The artists sat down at Make Room gallery in Los Angeles, where Yuan had just closed her exhibition of paintings and Koh was preparing to open his solo show during Frieze L.A.

Yuri Yuan and Terence Koh must have been friends in another life. The two artists had met a day before they came together last month in front of a computer at Make Room to Zoom with me. Yet, they immediately clicked. What bonded them in Los Angeles was Yuan’s solo exhibition at the gallery where Koh will open his solo in late February during the art fair Frieze L.A. Despite their very immature friendship, the duo was comfortable and open with one another, holding clear but also poetic understandings of each others’ works and personalities. They even realized they had both lived in Singapore at some point in their lives.

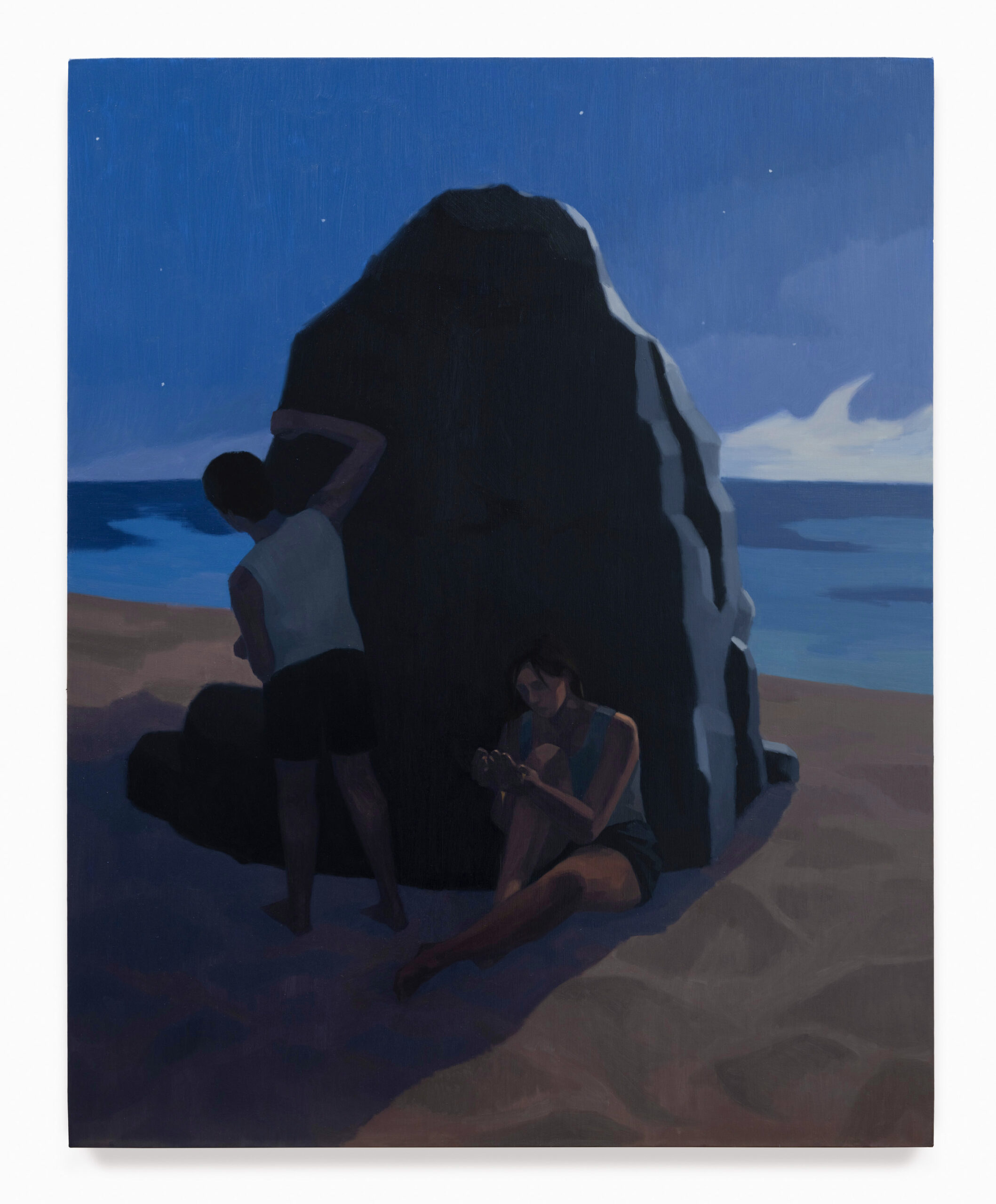

Yuan’s exhibition, A Thousand Ships, which closed in the first week of February at Make Room, included paintings of grey-hued urban contemplation. In various scales, they held sudden illuminations within the darkness. In the triptych Nothing New Under the Sun (2023), one panel was gloriously lit by a setting sun, the blindingly fiery disk above the horizon bidding the light’s final farewell for the day. This was the sun’s own swan song, washing the sea into orange on a summer day. The other panel is brightened by a street lamp, a tired flicker suspended above a metal pole in the nocturnal dimness. Nature is the common backdrop in most of the New Yorker artists’ paintings, but the city blues are instantly recognizable: a detached figure finds refuge in a dim corner, and a rain puddle reflects apartment lights unattainably far up high. In Love Affair (2023), a loft window is left ajar, conveying a sliver of the sunny day outside when the inside looks icy grey. A bunch of red roses over a pile of books yields the only source of colour.

Light and salvation have their own path for Koh. After a decade of delivering talk-of-the-town performances and installations in the 2010s, Koh had retired from the New York art scene’s see-and-be-seen energy and moved upstate. Back in the day, he had made a splash with his material-heavy performances, which he held within monochromatic, often times white, installations. Salt or beeswax were the materials he had occasionally turned to. These days, he lives in Los Angeles, where isolation has its own shape and feeling. New York’s almost palpable sense of being alone—while stuck in the sardine can-packed subway cars or waiting for the never-ending red light to change to “go”—is quite different from the City of Angels-type aloofness. Distance is rather more physical on the West Coast, where the gap between houses and tables also carves a separation between the bodies. Driving is necessary, as well as the acceptance of the necessity to take things slowly. Familiarity is perhaps more exclusive in L.A., and connections are more pre-planned. Perhaps for all these reasons, making small objects currently intrigues Koh—think intimate drawings of the subconsciousness as well as objects of a mysterious whimsy.

Below, the two chat about life on different coasts, the joy of contemplating light, and the pleasures of seeing a painting in person.

Osman: Isolation runs through both of your works. I wanted to talk about different forms of isolation and loneliness: there is the chosen lonely time and loneliness, which sometimes finds someone outside of their choice.

Yuri: I think there’s a difference between solitude and loneliness. Solitude, as you said, is choosing to be by yourself, and you might be very happy with it. Loneliness is perhaps more about the absence of other people. I definitely think my work is more about the solitude of living in a large city, of witnessing so many different things and being everywhere, all at the same time yet still feel a bit away. Imagine living in a stadium and observing everything with a solitary mindset. In many of my paintings, you’ll see the figure watching something else or turning away from the viewer. You’ll see them in this quiet place, thinking about something. This is not necessarily about being sad or depressed but just going through different emotions.

Terence: I actually have the same definition of solitude and loneliness. We all, as humans, experience loneliness. That is what I see in your paintings, as well. I see solitude, but I don’t see loneliness.

Osman: Winter is probably the loneliest season after a very social December spent with friends and family.

Terence: In LA, there is a different kind of loneliness. I perhaps chose to leave New York because I was lonely. No other city in the world probably experiences the feelings of being alone or too social like New York. You step outside of your apartment, and you are immediately faced with human energy. In LA, the experience is very different. You live within your cast of people, in your own zone, but you never get that intense connection like in New York. I don’t drive, so my mobility is even more limited.

Osman: There is the common notion of feeling even lonelier in larger crowds. How do you see social media affecting this sense of isolation, both stemming from being too close to our devices but also from observing others’ supposedly very full lives?

Yuri: Another thing Terence and I have in common is that we are not from here. I was born in China and grew up in Singapore, so I do not have family here. I rely a lot on social media to be in touch with my family and friends back home. I feel that type of loneliness, especially during the holiday season. I’m usually by myself working in the studio—for example, this holiday season, I was making these paintings. I think social media can be helpful in that way. I can keep track of other people’s lives and vice versa.

Terence: That is exactly why I quit social media two years ago. They’re just instruments. Social media is just another channel of communication, the same as when cavemen used to sit around and draw their stories. The problem is that we humans are not capable of balancing ourselves and our relationship to the machine. We are sucked into it. That said, I use my boyfriend’s Instagram to check my friends’ posts, though [laughs].

Osman: So you mess up his algorithm.

Terence: Exactly. But another reason I quit social media was because I didn’t want to be a part of the same art world algorithm, everyone looking at the same paintings on Instagram. When I see Yuri’s paintings standing physically at the gallery, I feel touched. The living human energy goes through the two-dimensional level. So, there is a way to break away from the device experience.

Yuri: When I make a painting, I think about it as an object that exists in space, not as a JPG, not as a PDF. I really appreciate when people can see the paintings in person and find small details that I left that might not be visible on their phones.

Osman: Going back to you both not being from here, how do you see home as a place of belonging as well as dwelling, as a safety shelter? What are the parallels or differences you see between each other’s works in terms of your approach to home?

Yuri: I’ve lived in so many different places. I grew up in China and moved to Singapore. Then, I lived in Chicago and came to New York for my undergraduate education. Home has become a lot more abstract than it was when I was a kid. It’s no longer a physical space. Sometimes home is my studio, where I feel the most comfortable and safe, or sometimes home is being with friends with whom I don’t have to put on a facade to perform a certain role. A lot of these paintings is about living in that ambiguity.

Terence: I like that we both lived in Singapore at some point. I totally hear what you’re saying. I’ve moved so many times as well, from Singapore to Canada and then to the U.S. When I do my installations, I always think of them as homes that I’m building for myself. The gallery is like being in a spaceship. Also, not just us but everyone in big cities is constantly moving because of things like rent increases or changes in personal lives.

Osman: The body is another mutual element in your practices. Terence, of course, you come from performance, but your installations also deal with another skin. And Yuri’s paintings put the bodies in surreal but also mundane, everyday settings.

Yuri: For sure. We are approaching the body through different mediums and discovering the relations of those mediums to the human body. When I made this body of work, I thought about the physicality of the gallery. In terms of size, this gallery is much larger than my New York gallery. How should I make use of this space? How can I bring a different bodily sensation through my paintings? Some of my paintings have these close-ups of the body, and others are removed from the viewer. Your point of view is in and out. You’re either peeking into someone else’s life, or a figure is right in front of your face. This experience is very different from installations where you are physically surrounded by a feeling.

Terence: I totally felt that when I walked into your show because my sense of a painting is always like peeking through it. I actually sense my physical body more when I see a painting, based on how I frame the view of the painting for myself. I’m reading a collection of short stories from the 1960s called Points of View. The book is edited to provide different points of view. That is how I see the body’s relationship with a painting, each being a point of view of the work. I, of course, use the body in my work too, but maybe more as a vessel, and it is still the viewer’s point of view to understand it.

Osman: Yuri, let’s talk about how you depict the every day but through somewhat of a surreal lens. Your previous show with Make Room was inspired by an unpublished Kafka text, so you seem to be interested in the absurd.

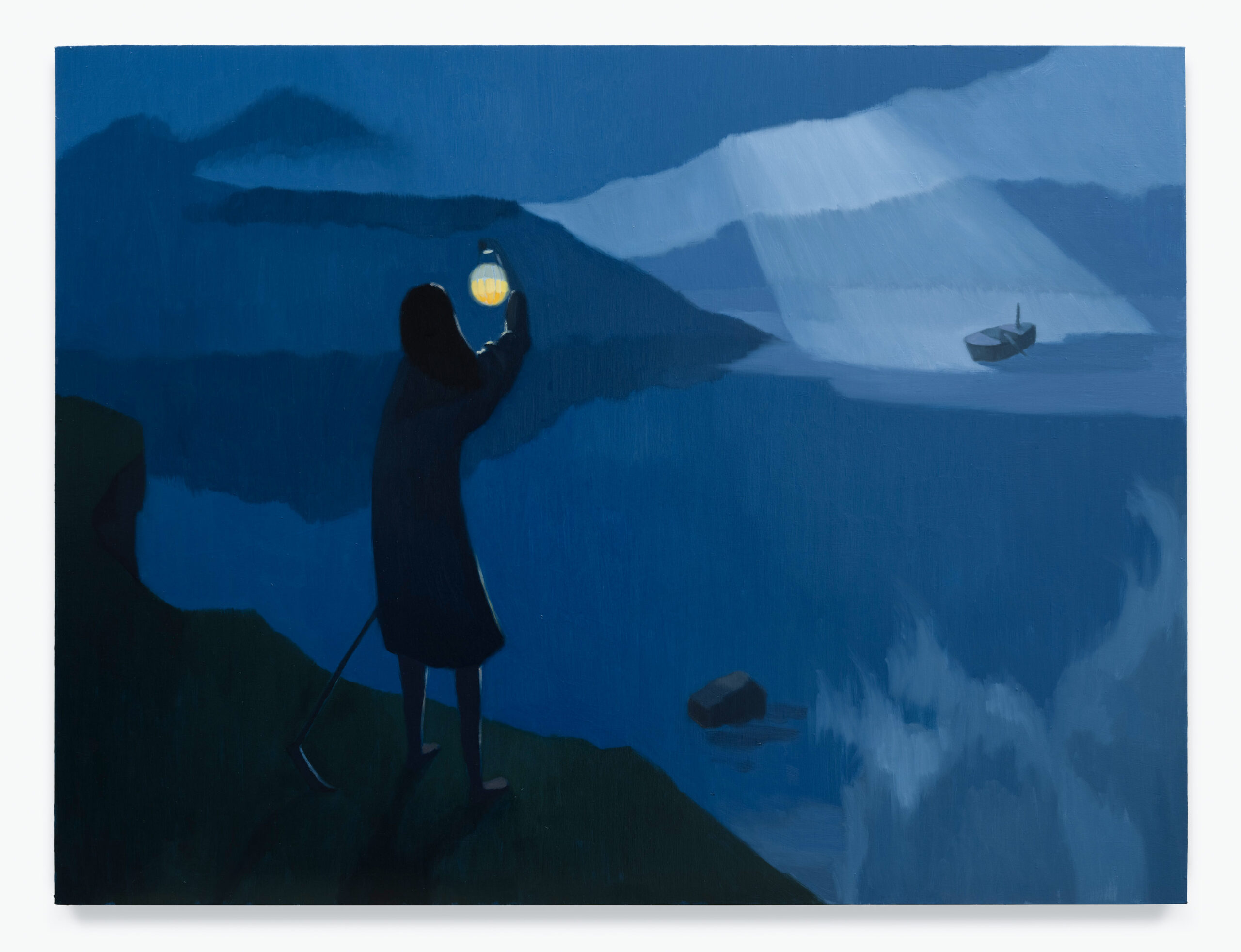

Yuri: There is a work in this show influenced by a Turner painting about pirates who operate by the coast. They pretend to be a lighthouse and hold a false light to attract the ships. I like this idea of something you thought could be your savior, actually being your doom. This is one of the few images that doesn’t come from a photographic reference in the show, and it is completely my imagination. Absurdity comes in here. I always encourage the viewer to spend more time with the paintings to discover these narrative layers.

Terence: I love this painting because I am obsessed with lamps, but I also see a Caspar David Friedrich influence, too. I get touched by so many things in this painting, and it reminds me of the whole reason I make art, which is to break time in space. When you introduce surreality into the work, it just shatters the reality itself.

Osman: Yuri’s exhibition is called A Thousand Ships and, Terence, in the past, you had a show called Empty Boat a few years ago. It is interesting that you both had shows with titles related to vessels, water, floating, and departure. Where does this mutual interest come from?

Yuri: My title is taken from Natalie Haynes’ book called A Thousand Ships, and she writes about the Trojan War from the women’s perspective. She talks about how these women were waiting for their husbands to come home and how every time the husbands were close to returning, something would happen along the way, and a few more years would be added. The expression a thousand ships is the metaphorical distance between them, which is not necessarily a physical gap. It can also be time, such as when we have relatives who live far away. Also, ships today are such a slow way of travel, but they still represent this ideal imagery of a journey as well as the anxiety of coming back home.

Terence: Maybe that is why we use boats and ships a lot because ships and boats are these homes that are always moving. Even though everything is chaotic around you, we are almost in a boat, in the ship that we created for us.

Yuri: But your boats are always empty—why is that?

Terence: I think it’s for the viewer to fill them.

Osman: Movement also has to do with adapting to a new life. As two people who lived in many places, how do you see the ship figure in terms of creating a new life in a new place?

Yuri: Every time I am in a different place, a part of me changes, including how I speak. When I’m talking to my mom in Mandarin, I sound a little bit more gossipy. When I’m chatting with my colleagues in English, or when I’m in New York, especially, I act in a much more professional way. In New York, I’m always in the mode of getting things done. Different places and different people bring out a different side of you. I see myself being assimilated into that environment. I think some people might be more resistant to that change. I easily adapt to change, but I also have the question of whether I am losing my original self. The fact is that so much has changed, and my personality has changed, so my taste has changed. Moving around different places brings a lot of existential questions.

Terence: Don’t we do what we do for all these crazy questions?!

Osman: Yuri, did you make the paintings for this show, knowing you will show them within an L.A. context? New York and L.A. have such different social landscapes that the audience here and there have different takes.

Yuri: I was aware that I was going to show in this space, so I definitely had more of the physicality of the gallery in mind, rather than L.A. as a city. Solo show is a great opportunity for you to present your work not just as a painting next to a painting next to another painting but rather as a full story, like making a film with an intro, climax, and an ending. My work is still very “New York” as far as I’m concerned. I observe people commuting everyday and carrying things around with tiredness on their faces—they are very much “New York struggles.”

Terence: Now that I have lived here and in New York, I know visiting galleries here and there are such different experiences. When you visit a gallery here, you probably won’t find any other galleries around, or at least within walking distance. Make Room is located within a bit of a cluster with Marian Goodman, Jeffrey Deitch, and David Zwirner, but they’re still around a 15-minute walk from one another. I also think that I became a studio artist for the first time when I moved to L.A. I always did installations, but when I moved here, I entered my own zone and realized I like being with myself and making tiny things.

Osman: Terence, could you talk about the new show?

Terence: After a year and a half of making tiny things, it will be an installation. I think it is just the vibration of the year that makes you say, “This is what I want to do.” I sense that this time, it will be about light and a tree.

Osman: Has Yuri’s show inspired you about what you want to show?

Terence: Definitely, because it has opened my eyes to different possibilities of existence.

Yuri: I think something we have in common in our works is the element of light. They’re not there as something given, but they are there as a metaphor. Sometimes, light in my work represents hope, or sometimes I subvert it for danger. I am curious how light will appear in your work.

Terence: I see so many versions of light in your paintings. Sometimes, it is a direct representation with a direct line of a sunset or a very subtle line just after the rain. For both of us, light is not just a physical light—it is a spiritual light, as well. Artists are like vessels which hold the possibility of giving out different ideas of light, whether it is a sunset or an understanding of God.

Written by Osman Can Yerebakan