Terence Nance traverses the wide modalities of film all while questioning the entertainment industry built into contemporary cinema culture. Nance is an actor, artist, filmmaker, musician, and writer, but above all, he’s transcending our collective understanding of cinema. His filmography includes short films such as You & I & You, Univitellin, Swimming in Your Skin Again and the HBO television series Random Acts of Flyness. With a visual lexicon that amalgamates to genre-bending abstraction, Nance is not concerned with adhering to traditional methods of seeing.

The montage led short film, Univitellin — currently on view at Nicola Vassell through April 20th — begins with a quiet, unconventional meet-cute between a man and woman on a bus in Marseille, France. Over the course of three and a half days, viewers witness a fated and fragmented love story end in poetic tragedy. From the title translating to “of one egg,” it’s implied that their narratives are destined to intertwine from the first candid moment they sit across from one another. Originally released in 2016, the film is now presented as an installation titled Swarm. The installation champions 84 hours collapsed into an eight minute film and split into two panel projection, mirroring the dual perspectives of the hero and heroine. The immersive form challenges viewers to orbit between the screens and situate themselves within the intimate halcyon between young paramours.

The show opened on an unruly windy late-March day, just a few blocks from the water of Chelsea Piers. Nicola Vassell’s main gallery space was transformed by a light blockade, separating the glass foyer from the pitch-black, red carpeted theater space where Univitellin plays on loop. Just beyond the rounded Richard Serra-esque screens, the show continues to a bright room of framed archival photos. Reverent observers lined the walls of the room while Nance stood centered, telling stories amongst the crowd — this is where we met.

Gwyneth Giller: These photos hold such significant presence in the space, can you walk me through the archive and describe how it relates to the show?

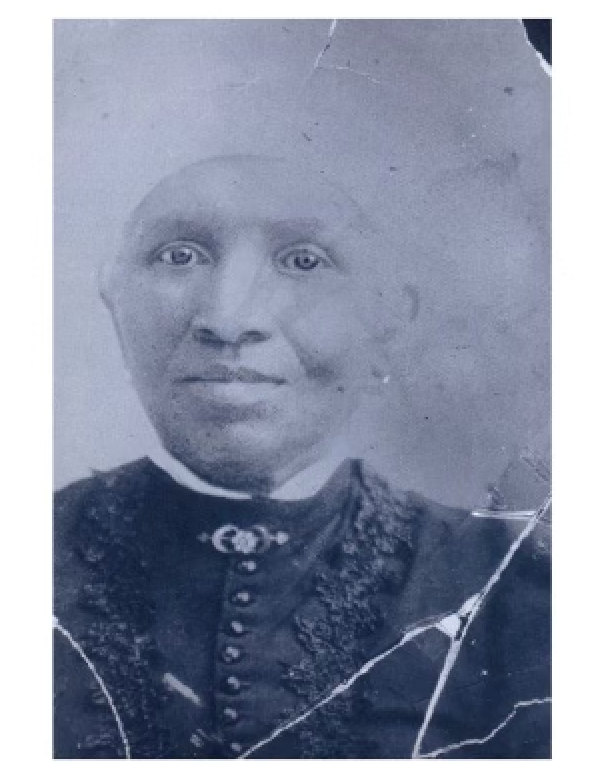

Terence Nance: There’s a photo of my mother in character as one of the three witches of MacBeth, the image was taken by my father. The second picture is my grandmother, Freddie, my father’s mother, also taken by my father. He’s a photographer, by the way [laughs]. This is an archival photo of my great great grandmother, Easter, who was a ritualist. She was born into enslavement and survived to liberation in Hays County Austin, Texas. There’s a yearbook picture of my mother’s mother, Lois Louise who was also a spiritualist. Another photo is one that I took of a person masking as Yemaya — queen of the sea and mother of all — in Recife, Brazil. The testament connecting these photos to the show is fractal, there are a few threads, one is naming the lineage of photography in my family and another is to ritualistically present them here. I’m just an expression of an assembly of people in my family.

artist and Nicola Vassell Gallery.

GG: Can you describe the trajectory that landed you here?

TN: I was born and raised in Dallas, Texas; the neighborhood I was born in was, at a time, called the State Thomas community. The Dallas of my parents’ generation was segregated. They’re from different places in Dallas, but mainly North Dallas, Hamilton Park which was a community built for black people during segregation. My mother is an actress and theater director, and my father is a musician now, but when I was growing up, he was in broadcasting and news photography. He’s always been an audiophile, a music collector, and a jazz head. I grew up being taken to Pharoah Sanders and Milton Mezzrow concerts and going to my mother’s plays, August Wilson, Shakespeare and so on. As a result, my siblings and I are artists, mostly musicians and photographers, making art was very normalized in our household.

Long story short, my family and going to school at NYU to study studio art have brought me to where I am now. I was also really influenced by my thesis professor, Luis Gispert, he understood cinema as art practice and massively informed my own view of cinema. To me, cinema is a deindustrialised art form, not an entertainment industry — it’s the act of merging audio and visual entities that invite transcendent experience.

GG: Do you often feature your family in your work?

TN: Yes, Random Acts of Flyness is written, coded and scored by my younger brother who goes by the name Nelson Mandela. My older brother Djore Nanceis a singer and actor featured in the first season of Random Acts of Flyness. My mother is pretty much present in all of my work as an actress. It’s a family situation.

GG: We don’t typically see short films screened in the white cube, how do you juggle the identities of filmmaker and fine artist?

TN: When I was in the MFA program, one of my advisors, Sue de Beer, saw something I was cutting together and she turned to me and said, “You need to decide if you want to be a filmmaker or an artist.” Initially, I was really offended and it’s taken me almost 20 years to understand the wisdom of the question. I’m not concerned with titles, I want to be in the practice of withdrawing energy from making a decision about my identity as an artist based on medium or media affiliation. I want to be in the present with whatever is coming through on a project and make a decision essentially based on geography — it’s a matter of where people will find themselves and how people will experience it.

Ultimately, that’s a naive thing to say because of the deep industrial system that impacts the arts, specifically cinema. One thing I’ve found is that it helps to be in a relationship with continuous practice so that you feel a facility that brings about ease. It’s an infinite question and I don’t think there’s an answer or resolve, but there’s definitely a balance. I think of the image of a tightrope walker oscillating, that’s what’s happening — an oscillation between day to day practice.

GG: Speaking of an infinite question, do you feel as though mysticism informs your work at all?

TN: Well, what’s your definition of mysticism?

GG: I want to avoid falling into the territory of any specific spiritual practice, so lets say: something all encompassing or evergreen.

TN: I actually haven’t used the word too much but what it’s bringing me to is the idea of a person called a “mystic,” someone who has a regular practice of going outside of a modernist, material-centric world and goes to an opaquely errant, mysterious and elemental based mindset; someone in conversation with the ethereal realms. I want to conceive of myself as a mystic in my day to day practice, but that’s very difficult because it’s not a typical industrial archetype.

GG: In Univitellin, there’s a moment when your characters reference certain things which shouldn’t be filmed or rather, can’t be documented properly — do you personally align with this idea?

TN: I do. I think there are images that shouldn’t be made. I don’t know if anything can’t be filmed. I think most centuries of experience came to be expressed by film but the question is: how accurately did they depict the embodied experience they’re referencing?

GG: In the film, you write that Hip-hop is one of those phenomena that can’t be properly expressed through cinema, can you explain?

TN: I think pretty across the board, the expressive feeling of Hip-hop and how we experience Hip-hop, in whatever way you understand it, is untapped. Cinema hasn’t figured out how to translate certain modalities of expression that Hip-hop possesses.

GG: Interesting point, so what’s your relationship to realism in your practice?

TN: I think the meta-quality of French New Wave Realism and its habit of reminding you, at some point in the movie, that you are watching a movie is an effective method for bringing an audience to awareness of the material. That’s something I use in my work because it’s a hypnosis trick. It’s the moment in the magic show that the magician tells you, “you’re safe now, but at one point I’m going to lie to you,” and then they can easily lie to you because they’ve positioned themselves as honest enough to tell you that they’ll manipulate the viewer at some point.

Thinking about ethnographic propaganda, there’s an intense distrust of camera and cinema as a colonial practice and fascist product so I think it’s really important to have disclaimers. There should be a disclaimer before Mission Impossible that says, “This is going to frame espionage as a heroic endeavor to further American Imperialism.”

GG: Most of your films present time through a distortion of sorts, why do you reject chronology and what does multiplicity have to do with it?

TN: I mean, who made time up? Sylvia Windsor talks about cosmology and astronomy being a universally orienting field in the sense that all earthbound beings observe the stars and the stars are all doing the same thing in synchrony. The sun is coming up and going down for everyone. So the best way for me to understand the thing called time, is through astrological movement.

GG: Okay, one last simple question, how do you make a film?

TN: You don’t make a film, you receive an offering.

Written by Gwyneth Giller