With his 80th birthday on the horizon, the polymath artist Terry Allen is grateful that so many people across so many generations celebrate the drawings, music, theatre and sculptures he’s produced over the last 55 years. But these days, Allen’s less interested in retrospectives and reissues than in what’s next.

As artists, collectors and the glitterati descended on LA for Frieze 2024, Allen and I managed to chat between his openings and concerts. Though I was interested in how his various artistic practices inform each other, our conversation took surprising turns: digging into his hardscrabble youth in West Texas, 1960s LA, and how “mystery” plays such an important role in creating art.

Despite living so many years on the West Coast and now in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Allen has never shed his warm but no-nonsense country drawl. Our meandering conversation in ways reflects the underlying premise of Allen’s kaleidoscopic output: that good art grows from following our curiosity, no matter where it may end up leading us.

Sammy Loren: You’re an artist who works across many mediums. Where does that impulse come from?

Terry Allen:

I think it’s that you make one thing and it escalates into something else. You use what’s necessary for whatever idea you have. So sometimes it’s minimal and other times it’s totally the opposite. I just let whatever happens happen, depending on what the piece is.

SL: How does your creative process differ when you’re approaching visual art versus something like songwriting or theatre?

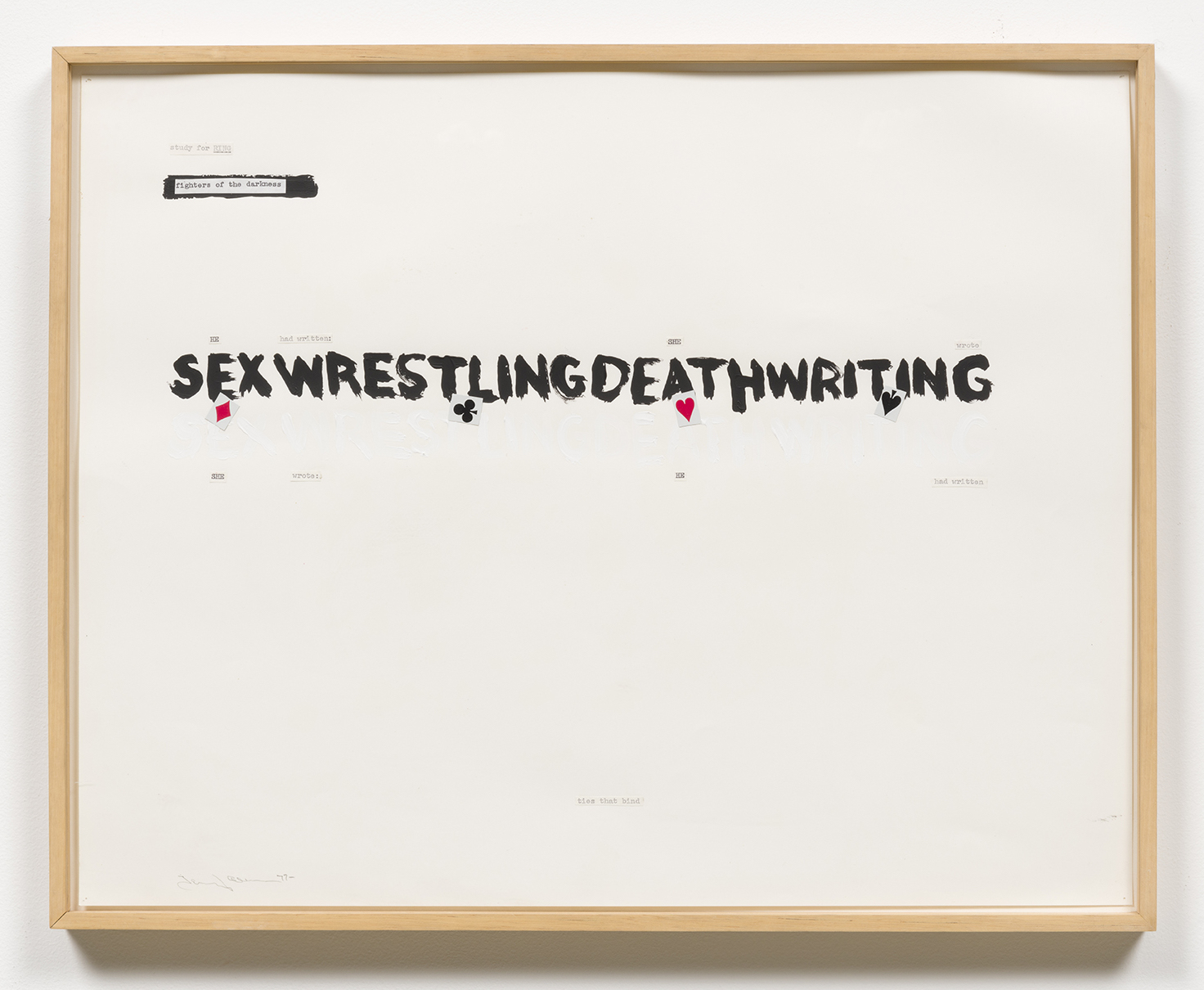

TA: I don’t think it is that different. They all inform one another so much. It’s kind of simultaneous. Juarez is a really good example because that body of work visually came about at the same time that I was writing songs. The songs informed the drawings, the drawings informed the songs, and it was built that way where the audio and the visual images fed off of each other. And that’s what the piece was about. It wasn’t about a particular drawing or a particular song but about when those two collided with one another.

SL: Talk to me about the challenges of working across mediums. Is one more challenging than the other?

TA: I think you go to whatever you need and you figure out how to do it. I’m a total digital dumbass, but I know a lot of people that aren’t, and I’ll use people to do what they do to help me make something. When you have an idea that you want to see, you figure out how to do it.

SL: The work you have up at Frieze with LA Louver is surreal and uncanny, which is different from your music, which has a distinctly Americana, Southwestern texture. Talk to me about the broader influences going into your work.

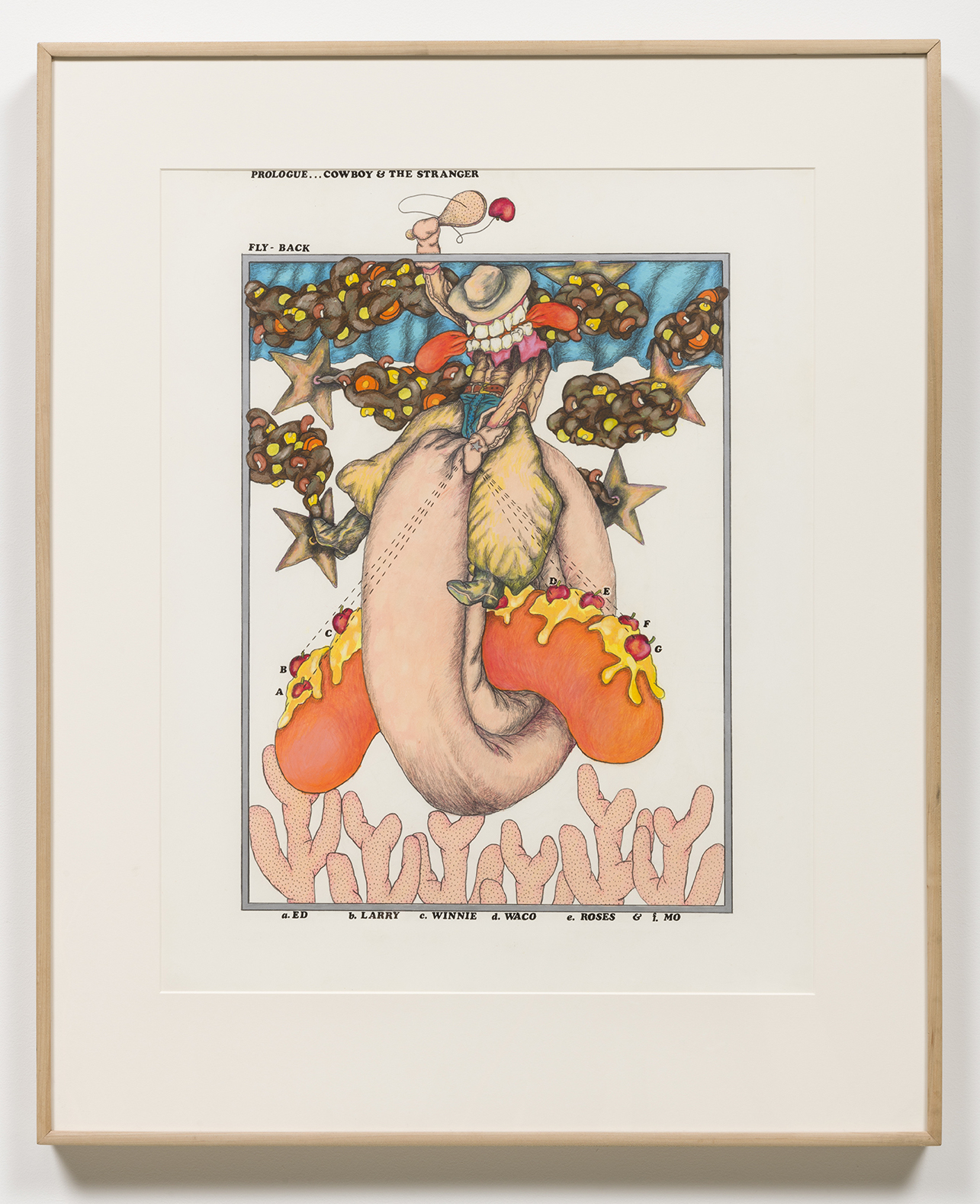

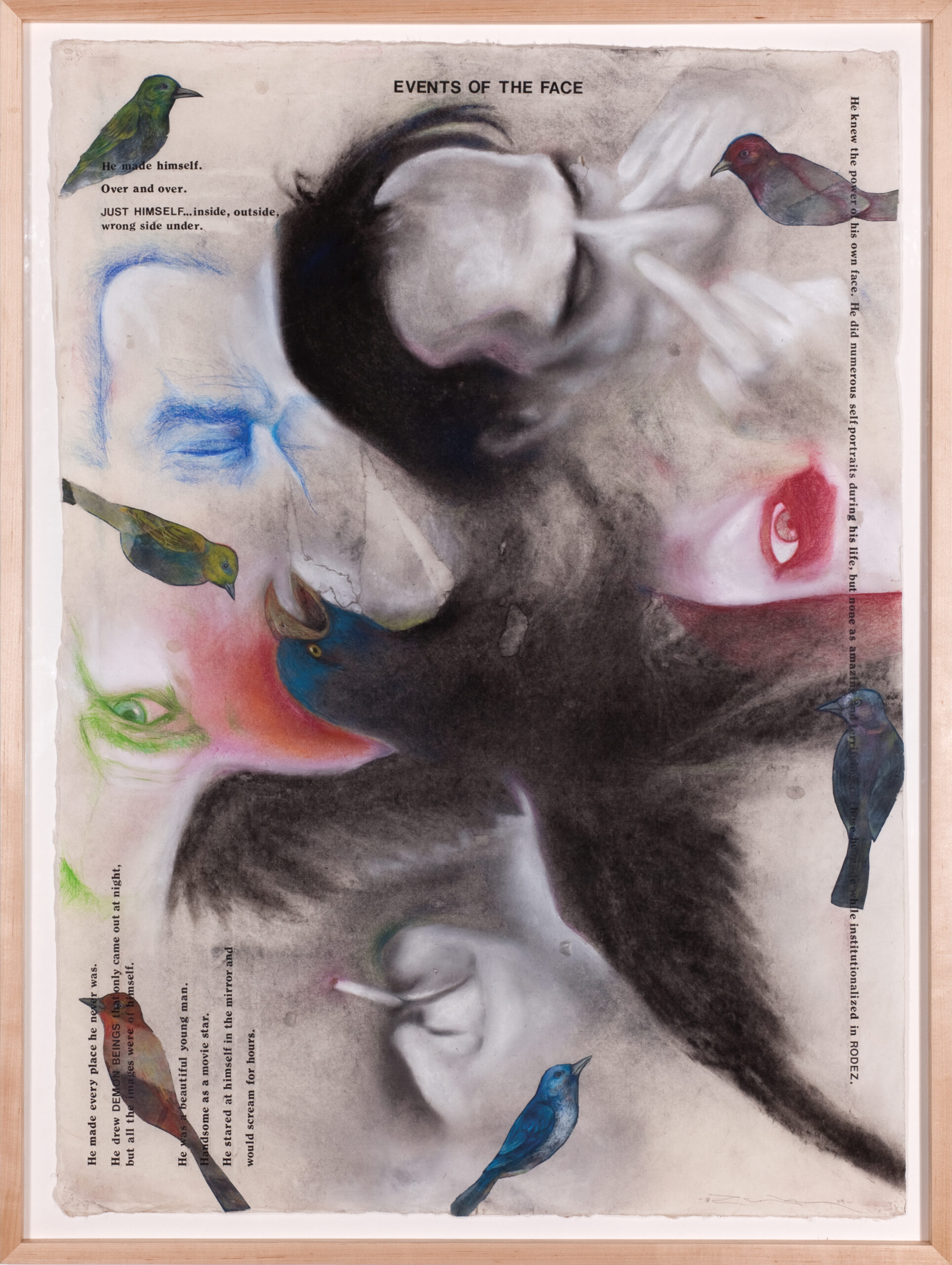

TA: The story is really important to me. This came from doing the whole Juarez body of work. I never actually made an image of a person. It was always geography or a room or a place of some sort, things that were happening in the air; it’s kind of unspoken and unseen, but there. The pieces at Frieze are from larger bodies of work, so it’s a little deceptive in the sense of juxtaposing how they work with one another. They’re separate pieces. I did a whole body of work on Antonin Artaud called Ghost Ship Rodeo, and there are several drawings and pieces in it. But it was a theatre piece and installation. I did a body of work called Dugout, which was built on stories that my folks told me when I was a kid that started out as a radio show I did for NPR. I’d always wanted to put these stories together cause my father was a pro baseball player born in 1886. My mother was a professional piano player and was born in 1905 in a dugout. When I had the chance to do this radio show, I organized those stories into narratives with this man and this woman. And while I was working on that, I started to get ideas for images. Five years later, I started making a group of drawings, and there are a couple of those pieces in the Frieze show, too. So it was all of those things happening at once, but they weren’t planned initially to happen at once. It just came.

SL: It’s interesting to hear you talk about your folks. You grew up in West Texas, right?

TA: Yes. I grew up in Lubbock. I’ve always lived in the West. I lived in LA all the ’60s and then the Bay Area for a good part of the ’70s. We were in Fresno for a long time in the San Joaquin.

SL: What was it like growing up in West Texas? How did you initially find your artistic voice in a place not known for the arts?

TA: Well, Lubbock is pretty well known for producing musicians Buddy Holly, Waylon Jennings, and Joe Ely. There are a lot of people that come out of that part of the country music-wise, but when I was a kid there, it was a very conservative town. My dad was a pro ball player up until he got too old to play ball. He had an arena where he put on dances and brought in great touring bands at the time. Friday nights were all Black dances, and Saturdays were all country dances, and there were great people touring like Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, T-Bone Walker, and B.B. King. I grew up working at the arena and selling buckets of ice with lemons so people could mix their drinks under the table because it was a dry town. But the first real thing that moved me was rock’ n’ roll. It opened the door to the outside world.

SL: How did you wind up in LA?

TA: The choice was between going east or going west, but I never thought about going east. When I came to LA, it was the first time I left Texas. The 60s were a great time to be in LA because everything was changing and in a state of flux, especially in the arts and music. All of the diehard ‘-isms’ were falling apart. New things were happening, people were merging with one another and making weird hybrid pieces.

SL: What was your scene like in LA back then?

TA: We lived all over LA and moved many times in the middle of the night, you know, that kind of deal. We didn’t have any money and couldn’t pay rent. We’d split and go somewhere else. It was when I got to art school that I met like-minded people for the first time in my life. I wanted to make something. To either play music, make objects, or write stories. There were other people who wanted to do the same things, and that was a huge encouragement. You felt like you became a part of a family that you didn’t know existed. It was a very fertile fertile time. Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable came to the Crescendo Club, and the Velvet Underground was a house band. The Living Theatre came to USC, and I remember my wife and I went to see that. It had a huge effect on us because of our courage and nerve. Things were exploding, and everything was new.

SL: Many artists who’ve been around a long time are often nostalgic and fetishize the past. Your work, by contrast, has a very forward-feeling spirit. What interests you in the future?

TA: I’m more curious about what I don’t know about than what I’ve already done. You wanna go into those areas that are mysterious to you because that’s where work happens. That’s been a constant with me. There’s this book coming out, which is a biography. There are a lot of reissues of my old records, a retrospective, and things that deal with the past. I’m very appreciative of it, but at the same time, I want to concentrate my time on getting back in my studio and working on some new ideas that I have. It’s that way for a lot of artists, the ones that I know anyway. They all seem to be chomping at the bit to face the future.

Written by Sammy Loren