“Comedy is simply a funny way of being serious.”

—Peter Ustinov

Claims are that laughter will make you live longer. Suggestions are that it will improve your heart function by increasing the flow of blood and, thus—maybe—prevent a heart attack. Humour is also supposed to diminish stress and be equivalent to the time in minutes spent on an exercise bike or rowing machine. William Makepeace Thackeray knew best about wellbeing: “A good laugh is sunshine in the house.”

For the longest time—until the onset of dotage—I laughed little and cried never. These days I laugh all the time, especially at the plight of others as well as my own, and cry at the drop of a hat, including during über-sentimental movies. And also now I tell jokes. Since I am often depressed, you might think that odd. However, most comics are depressives. As Charlie Chaplin suggested: “To truly laugh, you must be able to take your pain and play with it.”

Until I was thirty, I would never speak in public, certainly not at a big public event. I can now talk to thousands with equanimity. I finally surrendered because the event about historical designers I had been invited to address was being held in the same hall—the Cooper Union in New York City—where Abraham Lincoln and Alexander Hamilton had delivered speeches. I wasn’t nervous because I already knew—from my time in an ashram—that resisting being nervous will make you shake. When you fully accept a condition, even pain, it will disappear.

In the three or more decades prior to my surrender to public speaking, I had been on stage in a number of plays during my university days. But acting is far different from being me, exposing me, standing there naked. Every actor will tell you this.

The first time in front of a crowd I played two very small parts in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Because it is a metatheatrical production, the audience is sometimes embraced within the play itself. In one role, as the Belligerent Man, I ran down the aisle from the back of the theatre in period 1910s dress, including a fedora, exclaiming: “Is there no one in town aware of social injustice and industrial inequality?”—words now embedded in my memory. I frightened the audience.

“These days I laugh all the time, especially at the plight of others as well as my own”

These were initial tiny intern-level parts in the drama ensemble. Later on, I played the lead in Philip Barry’s Hotel Universe, a drama about reunited friends on the Côte d’Azur. My dialogue seemed endless. The production is very, very long with no breaks—a single act. I made sure that I peed just before going on stage. I still have nightmares about forgetting the lines.

After the Barry play, I sought comic roles, especially ones that were small and with much less dialogue than the leads. Not that those are the ones the director chose for me. I had the most success as Beverly Carlton in Kaufman and Hart’s The Man Who Came to Dinner. At the time, I was about eighteen and always playing middle-age men, made up to have grey temples.

In The Man Who Came to Dinner, I had to sing a song and play along on the piano. I studied the piano as a child, but not for long because I didn’t like the instructor. And I also refused to learn from my mother, who, unlike my two brothers, never played well. She inherited an electric organ that she played with the vibrato full up, just like in the 1940s radio dramas that I had listened to obsessively as a child. When I visited her in Florida as an adult, she would ask: “Would you like for me to play you something?” During my adolescence I was brutal to her but now I responded: “Maybe later.” My two brothers are highly accomplished professional musicians, one favourably compared to Django Reinhardt.

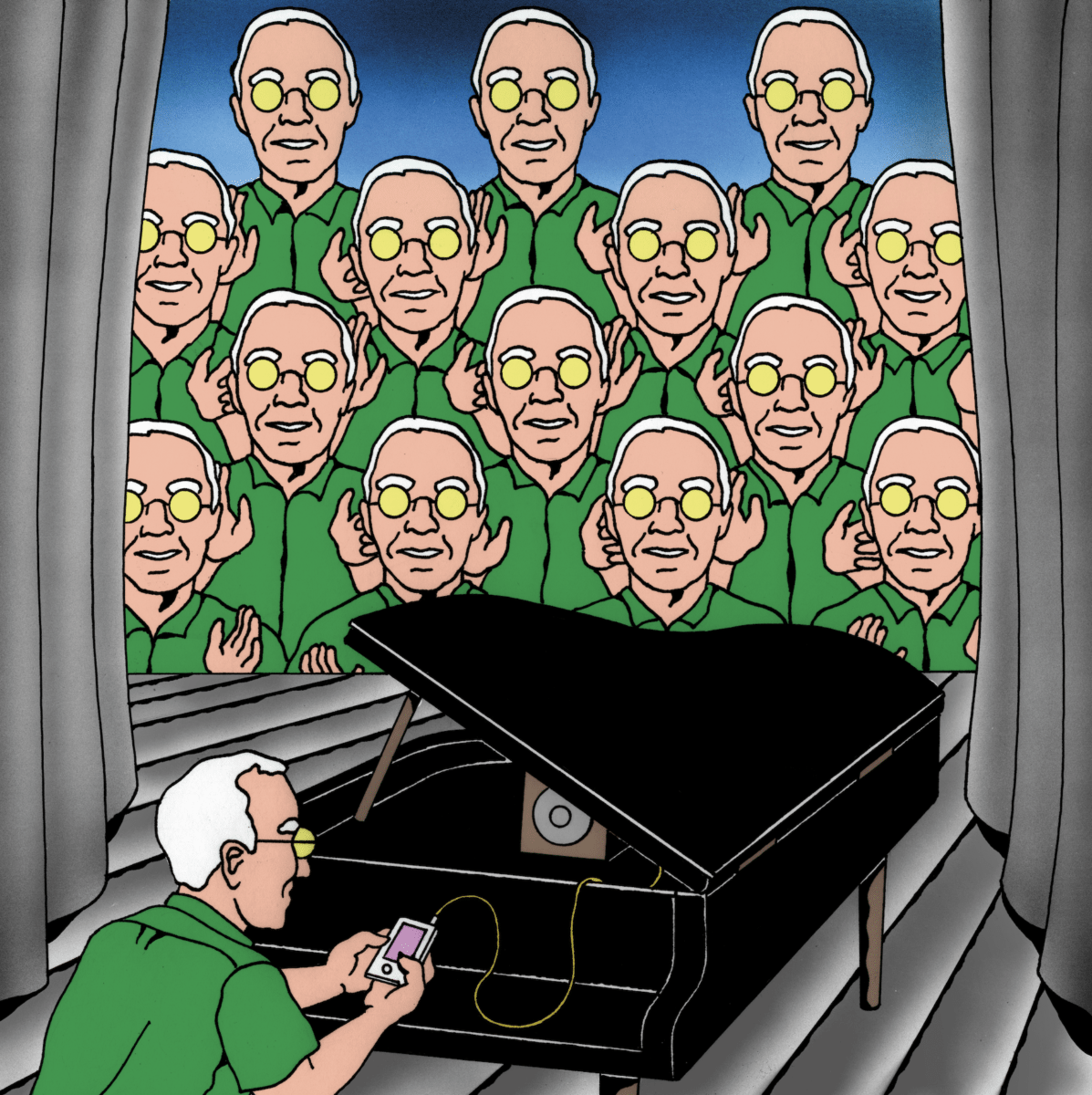

I enlisted a friend at university to play the piano for me in The Man Who Came to Dinner. It was located offstage and the sound emanated through a stage-set window. The piano that I faked playing was placed onstage so that I faced the audience who had no view of my hands. I did a number of flourishes, visibly raising and lowering my hands. My performance was so outrageous that I drew attention away from my pedal action, which was not accurate. The audience was invited onstage to meet the actors at the play’s end; a woman came up to me and told me how good my playing was. I met her with the words: “Thank you, ma’am.” I sang-talked like Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady. Neither I nor Harrison could sing well, but speaking the each word of the lyrics on the note of the music creates the illusion of singing.

When I was speaking in Miami a couple of decades ago about a new book I had written, I diverged from my script and reproached President Bush, causing some people in the back row to walk out. I thought what I had said was funny. I learned two lessons: (1) don’t try to be funny, and (2) address politics only in private.

I don’t remember most of the funny things I have said. At one job, my assistant kept a record of them; I refused to take a copy. On another occasion I violated my rule about trying to be funny during a speech at the design academy in Jerusalem. The government did not provide a fund for promoting industrial design, which is absurd because the academy and other schools there train thousands of designers. An array of governmental and military people was in the audience, so I thought I would make a joke about the circumstances. Unfortunately there was no voice in my head screaming: “No, Mel, no! Do not do this! What are you thinking?”

Possibly if I had omitted any reference to the Palestinians or to former Vogue editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland’s vapid observation about pink’s being the navy blue of India, it would have gone down better. Actually, I should have made no jokes at all, especially ones that referred to tanks and the military.

“Unfortunately there was no voice in my head screaming: ‘No, Mel, no! Do not do this! What are you thinking?'”

It was stupid of me because I already knew that humour and worldviews are local. And I wasn’t a local. However, I made up for it when I wrote: “Israeli design is the world’s best-kept secret.” The design community embraced it and also me because my comment was understood to mean that Israeli aesthetics and ideas are imaginative and unique but regrettably unknown. To the contrary, I made an observation about contemporary French design in Graphis, a publication that frequently got me in trouble for my claims. I said that there are few contemporary French designers who are widely known and that the country is stuck in the eighteenth century.

If I have learned anything about the French and probably every other nation it is that they can make fun of themselves and of everyone else but we—uncultured clods—are banned from making fun of them. Of course, there is a difference between “laughing at” and “laughing with” someone. And there are jokes as art or art as jokes, such as political cartoons. One of my favourites features Saddam Hussein. He leans forward and enquires: “Hey, America, miss me yet?”, suggesting that, when he was in charge, Iraq was stable and that regime change was folly. The original cartoon has been reinterpreted over and over, on T-shirts and, of course, in memes. The subject matter is dire but the cartoon is hilarious.

He who laughs last laughs best.