I’m not accustomed to waking up at sunrise. On this occasion, however, the sky provides a beautiful backdrop to my call with Silas Munro, as it nears midnight in California, where he is based. Munro identifies as a design activist, nurturing a hybrid practice that involves running his studio Polymode, teaching at Otis College of Arts and speaking about Black design histories. Today, I’m listening to him trace the lineage of his research into queer publications designed during the Harlem Renaissance.

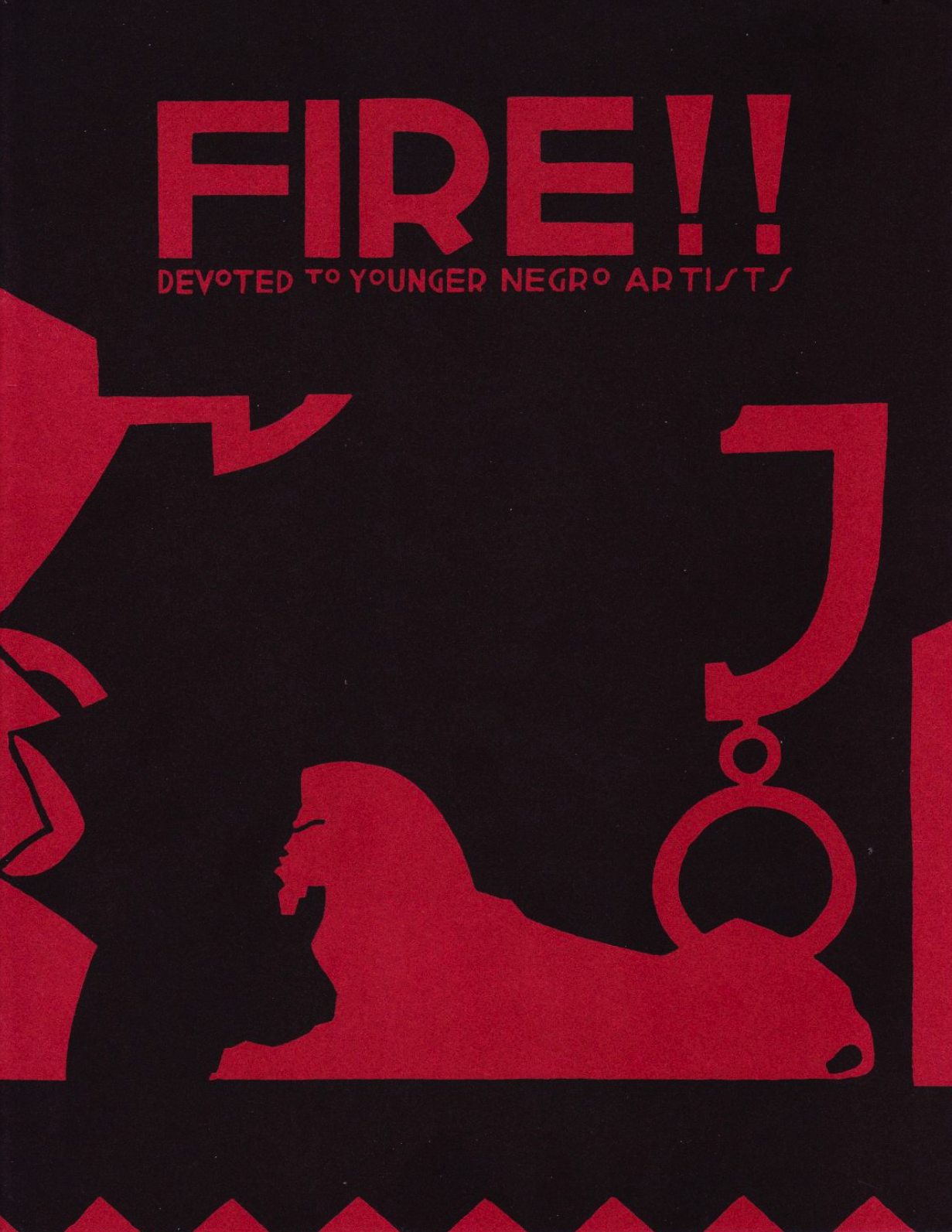

“I’ve been looking for a connection to history that makes sense for me. Being queer and Black, there aren’t a lot of models from history, particularly in terms of design.” Munro’s discovery of an ethnographic interview with Richard Bruce Nugent, one of the founders of a publication from the 1930s called Fire!! Devoted to Younger Negro Artists, prompted him to focus his research. He began to examine the conditions that allowed for Fire!!, one of the few queer Black publications of the time, to blossom. “When we think of the Harlem Renaissance, we think of Gleam of Glitz, of Black fabulosity.” It is amidst this glamorous backdrop that the story begins.

In 1925, radical thinkers like Marcus Garvey were urging the Black community to take pride in their African heritage by espousing Pan Africanism. WEB DuBois was enamoured with the concept of the “Talented Tenth”—the idea that if Black people could educate themselves and embrace sophistication, they could transcend the crisis of slavery. Amidst this cultural awakening, a professor called Alain Locke was dismissed from Howard University. As the first Black Rhodes scholar, Locke had studied at Oxford and gone on to chair the philosophy department at Howard, but was fired for working to gain equal pay for African American and white faculty at the university.

“There’s so much tension between notions of queerness and straightness and blackness and whiteness”

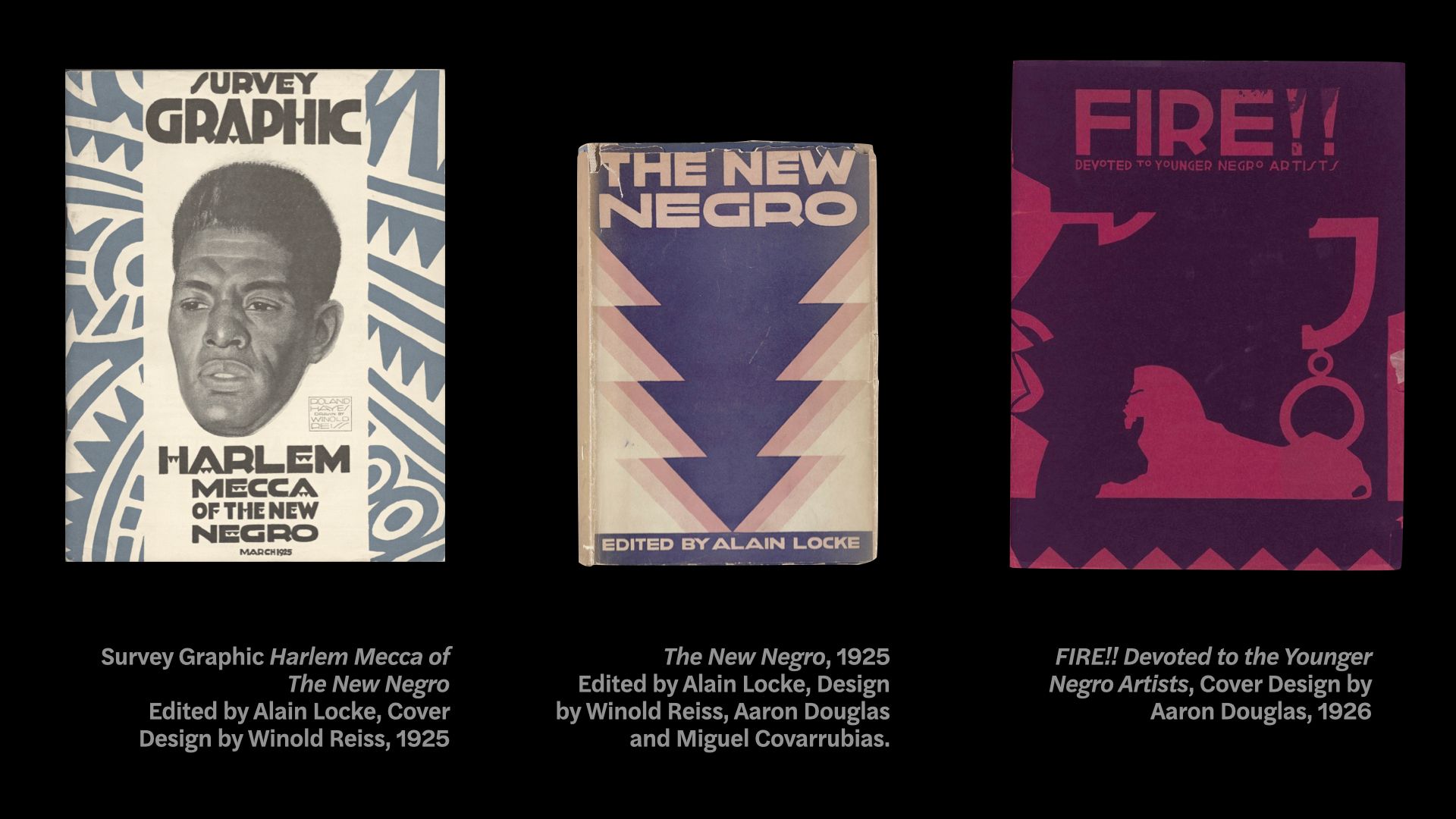

During this same year, he was guest editor of the March 1925 issue of the Survey Graphic—this special edition was titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro”. According to Munro, Locke acted as the “conceptual glue”, bringing together Black writers and artists to birth the movement that would later be known as the Harlem Renaissance. Munro explains that Locke wanted to change society and change the world, but his aspirations differed from those of Dubois or Garvey because he was afraid of being outed. “He didn’t feel safe in the activist spaces of the time. And rightly so, because a lot of that was connected to the Black churches… which were very patriarchal, very Christian, very homophobic. It is a problem that still exists to this day in Black culture and community.”

Locke’s idea for The New Negro, the second publication that created the conditions for Fire!! to emerge, was sparked after a trip with the poet Langston Hughes, where the two of them spent weeks together wandering around museums in Paris and Italy. Hughes, an attractive young poet, is believed to have been bisexual, and it is likely that the two of them embarked on an amorous relationship. Locke was enraptured, but in Venice they had a falling out. Nursing a broken heart, Locke retreated to an Italian seaside town. Here, in extension to the work he had begun with the Survey Graphic, he wrote a text outlining his concept of The New Negro, for which Hughes was very much his muse.

In the autumn of 1925, Locke returned to the States. He sought out writing from Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Bruce Nugent to create The New Negro, a new anthology of Black creativity. He also commissioned Winold Reiss, a German Austrian painter and designer, who was responsible for creating the visual language of the anthology, which Munro coins as “Neo-African Art Deco”. Reiss pinched typography from the art deco movement and sutured it together with influences from African sculpture and other colonial artefacts that had been harvested from the slave trade.”

In the midst of this, a copy of the Survey Graphic found itself in the hands of Aaron Douglas in Kansas, who immediately travelled to Harlem to meet Winold Reiss (who illustrated for both Survey Graphic and The New Negro) and became his apprentice. Reiss encouraged him to look at Africa for inspiration. “There’s the colonial gaze but it’s empowering this Black American beauty at the same time. I find there’s so much tension between notions of queerness and straightness and blackness and whiteness. As someone who is biracial, who has a white father and an African mother, it makes sense to me.”

Meanwhile, Nugent and Hughes met in Washington D.C., after the long European soirée where Hughes had rejected Locke. Munro recalls Nugent’s memory of their first encounter. “[Nugent’s] meeting this sexy young guy who had written poetry and published it, who had lived on a ship and travelled the world.” They met at the house of Georgia Douglas Johnson, a wealthy writer who was known for hosting “Saturday Salons” for friends, who were often authors. “It’s like this love story—they both live blocks away from Georgia Douglas’ place, and they literally spend the night they meet just walking back and forth between their houses talking about poetry… it’s so queer.”

“Design is such a sensuous act. To make it and consume it involves all your senses”

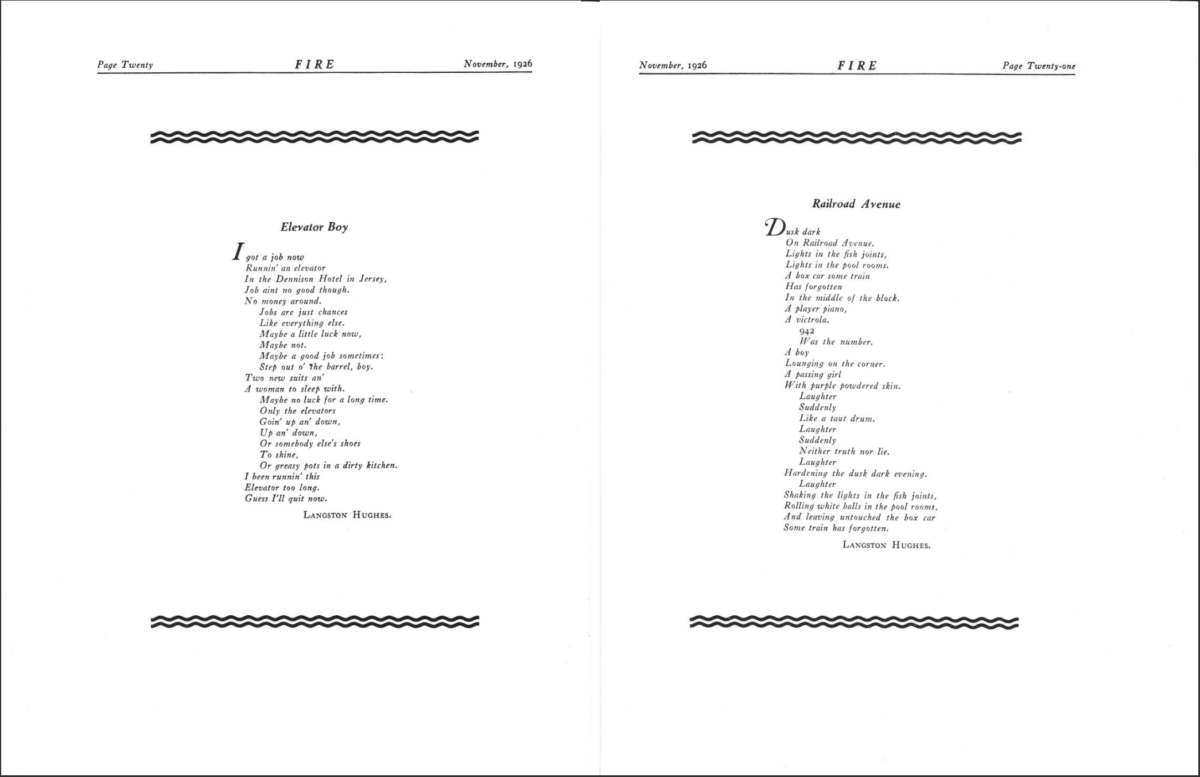

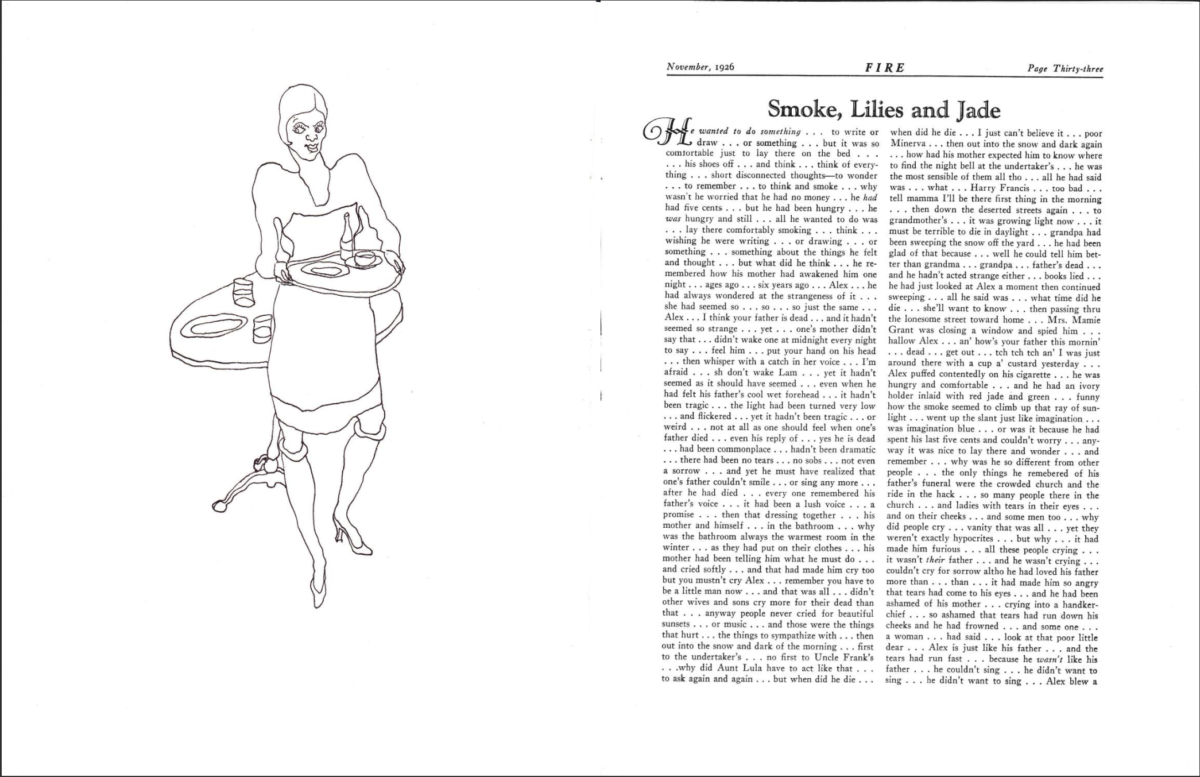

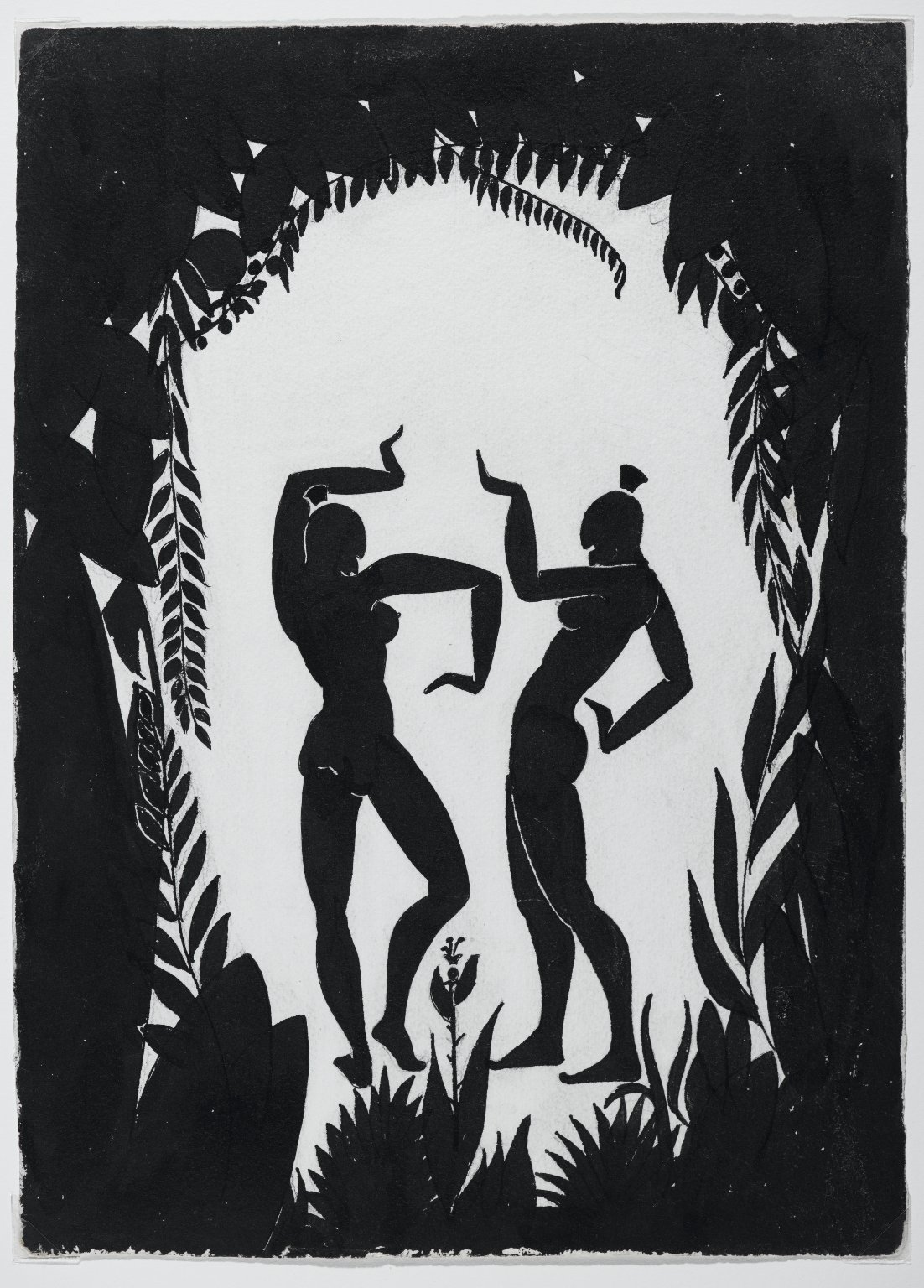

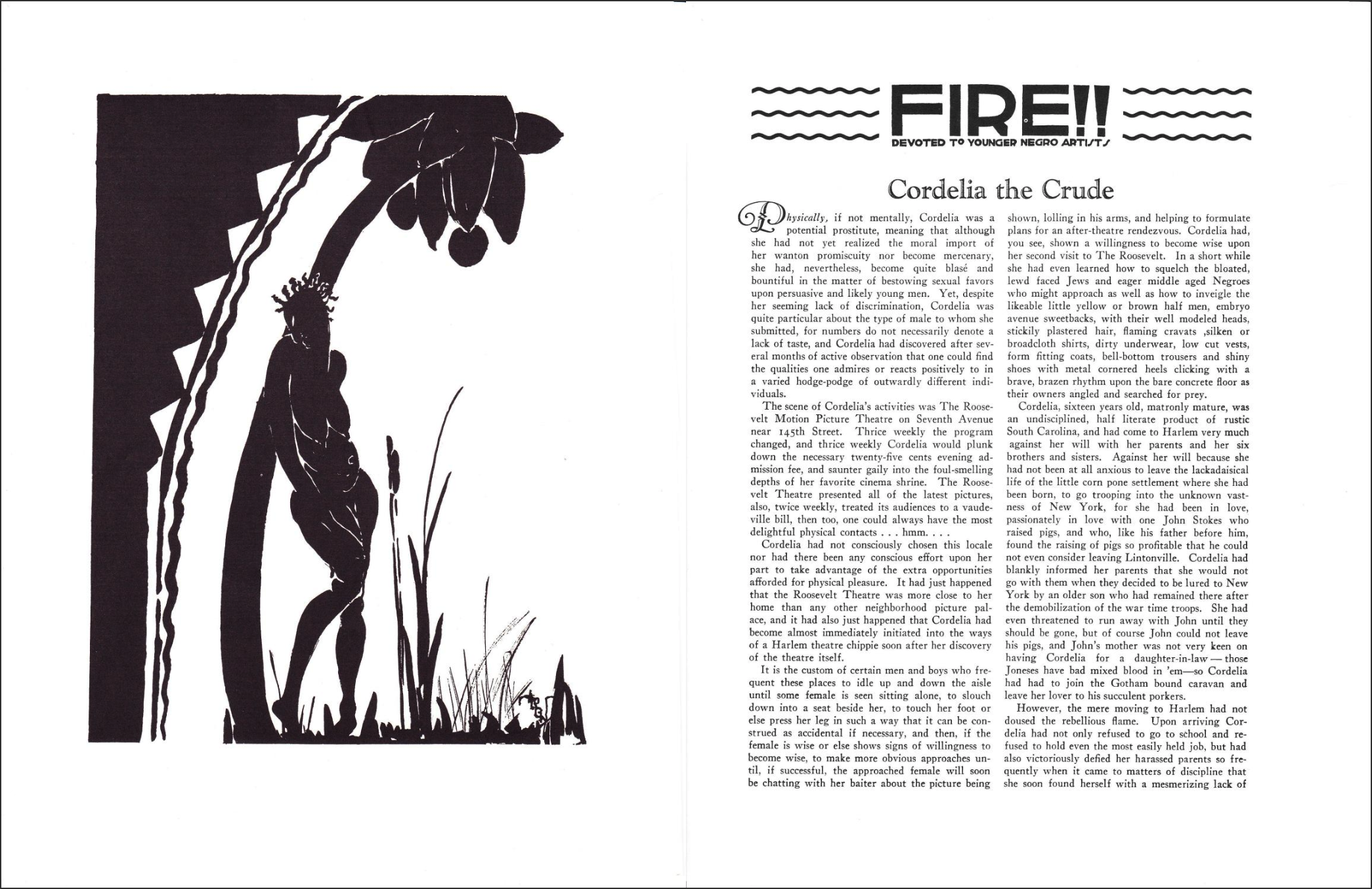

Nugent, Hughes and Douglas came together to create Fire!! Devoted to Younger Negro Artists in 1926. The publication reads as a love letter to the young queer Black community, replete with poetry, plays and short stories. Douglas evolved the style that Reiss had pioneered, including ornate Victorian detail in the typesetting, juxtaposed by bold, graphic imagery. The unashamedly erotic publication was very controversial. Nugent made the decision with Wallace Thurman (who guest-edited the issue) to try and get it banned in Boston in order to gain more attention. He wrote a story called Smoke, Lilies and Jade about two Black women who have a tryst, pairing it with stark, sensuous illustrations.

- Spreads from Fire!!, Courtesy of POC Zine Project

“It’s the first time anyone has published a story about two queer POC people having a sexual relationship, and it’s just really fucking groundbreaking,” Munro emphasises. What is the significance of archiving those stories in print? “It’s about taking a stand against shame—the equivalent of the sex positivity that we have right now. [They’re] speaking their truth and making it tangible. I think that design is such a sensuous act. To make it and consume it uses all your senses.”

Only one issue of Fire!! was ever produced, and a heavy dose of irony was doled out when the publication’s headquarters burned down. “It’s such a painful, physical form of destruction of the archive where that moment in time really could have been lost.” The only reason it survived was because Nugent lived until 1987, and found other younger collectives of Black queer creatives who could keep the history alive. “The fact that it’s in print means that we then get this account of something that is usually erased or imprisoned or beaten or harassed, so the magazine is literally a safe space for other likeminded Black artists. The significance that a publication can have to capture a moment of culture, to give form to things that are unconnected or intangible, that’s what makes them so interesting.”

So how do these queer, Black lineages fit within the Eurocentric, Bauhaus-loving design canon? “What comes with that white male European perspective is this [idea] of design as science, as something that’s analytical… Even though I do use some of the analytical tools like sequencing and textual research and going through archives, there is something very much that’s trying to keep this story alive, and that’s why I like the gossip! It’s that human emoting; it is storytelling. That’s the most interesting part of history to me.”