In the first week of January 1945, the New York Times Magazine published “A Teen-Age Bill of Rights”:

I. The right to let childhood be forgotten

II. The right to a “say” about his own life

III. The right to make mistakes, to find out for oneself

IV. The right to have rules explained, not imposed

V. The right to have fun and companions

VI. The right to question ideas

VII. The right to be at the romantic age

VIII. The right to a fair chance and opportunity

IX. The right to struggle toward his own philosophy in life

X. The right to professional help whenever necessary

Teenagers have long occupied a curious space between childhood and adulthood, aspirational, but not yet fully empowered by society. There is an insatiable yearning attached to our experience of teenhood, as we demand the respect afforded to “grownups”, while largely disregarding the responsibilities that come with it.

As Jon Savage puts it in Teenage: The Creation of Youth 1875-1945: “This sense of being lost is inevitably endemic to adolescence: adrift in a world made by adults, not for you.” The boldly laid-out teen commandments in the New York Times Magazine demanded something different, and were the result of a serious study by the Jewish Board of Guardians which aimed to offer practical guidance to families. They perfectly evoke the frustration that arises when parents and guardians are unable to take their children seriously. After all, the family is often the first structure that we find ourselves confined by, as we take our first steps to encounter the world on our own terms.

Of course, teen angst is more than just growing pains. Almost since its inception, the term “teenager” has been used as a marketing term by advertisers, manufacturers and brands to speak and sell directly to this newly empowered consumer group. It was in the 1940s that the shift from the term “adolescent” to “teenager” first took place, initially often hyphenated as “teen-age”.

Jon Savage explains: “The invention of the teenager coincided with America’s victory in the Second World War […] Indeed, the definition of youth as a consumer offered a golden opportunity to a devastated Europe. For the last sixty years, this post-war teen image has dominated the way that the West sees the young, and has been successfully exported around the world.” It is no surprise that teen angst has been similarly packaged over the years, from pop bands managed by much older executives to blockbusters chronicling the melodrama of the all-American high-school.

Beyond this mass-market approach, the pleasures and pains of teenhood have proved an endlessly rich subject for countless artists, writers, musicians and directors, who have sensitively reflected the nuances of what it means to grow up, and creatively expressed the true intensity of adolescence.

CLIQUES AND GANGS

“You can’t sit with us.” So goes the famous line from Mean Girls, the 2004 teen comedy which dissected the cliques that divide the high school canteen, classroom and beyond. The desire to fit in is perhaps strongest during those crucial years, when social rejection is felt most keenly and peer approval means everything. Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s film Center Jenny, part of a larger installation first shown during the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, attempts to conjure the context in which toxic group dynamics can develop. Futuristic and frenzied, it depicts a dystopian camp where all pupils are named Jenny, in a direct allusion to ultimate conformity. They scream instructions at one another, forcing a number of aspiring “Jennies” through a series of manic challenges and cruel rituals in order for them to ascend to “The University”.

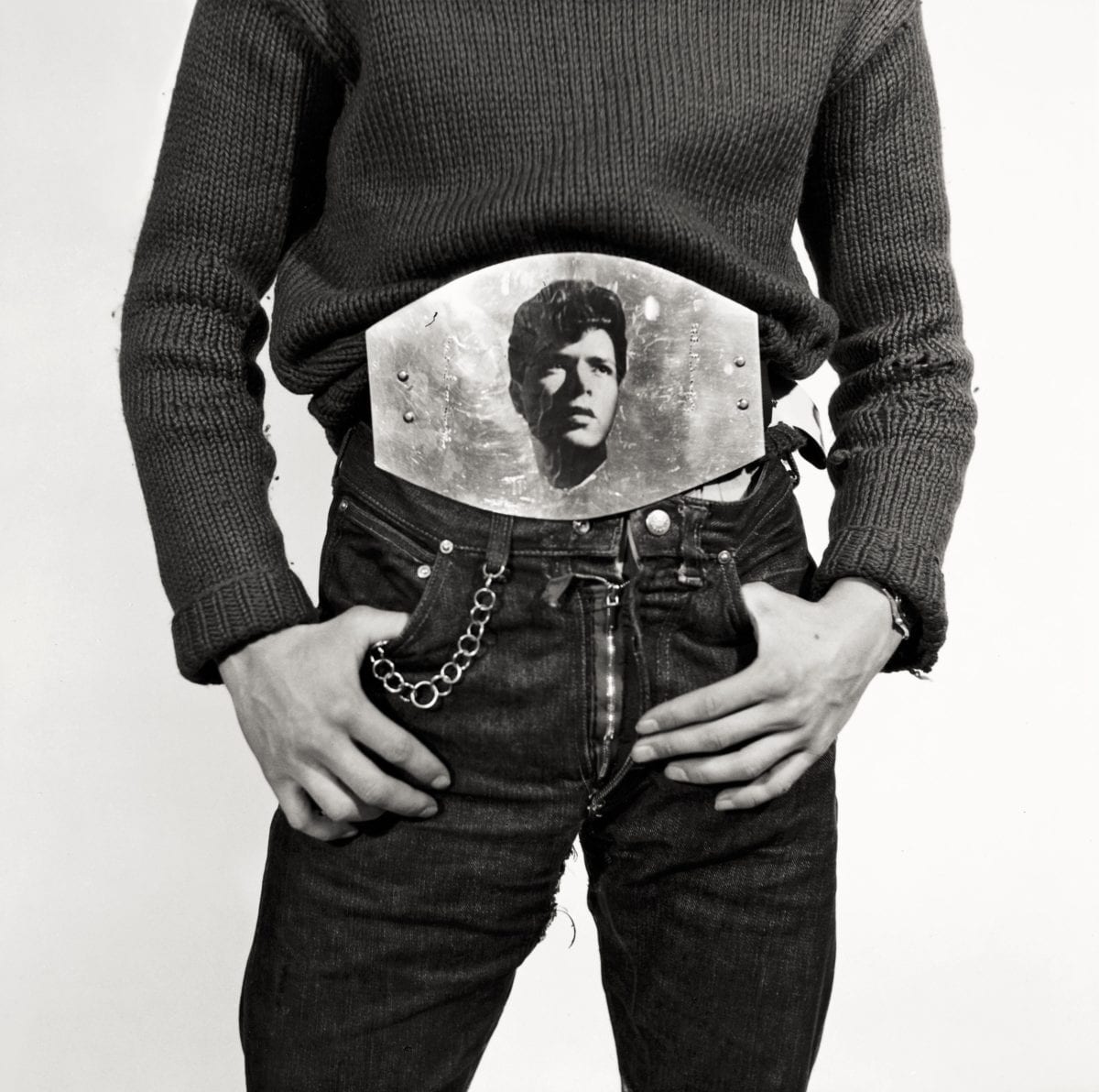

The teenage gang can be as seductive as it is threatening, and the affirmation of belonging to a distinct group is frequently expressed through visual cues. Swiss photographer Karlheinz Weinberger documented an Elvis Presley-obsessed group on the streets of Zurich from the 1950s to 1970s, in a series of remarkable, provocative images that, until recently, were lost in obscurity. His subjects pose casually and relax unguardedly together, united in their obsession with the rock’n’roll idol, who is emblazoned on their denim clothing and oversized belt buckles.

“The teenage gang can be as seductive as it is threatening, and the affirmation of belonging to a distinct group is frequently expressed through visual cues”

Ryan McGinley made a name for himself in New York in the early 2000s with his hedonistic photographs of (often nude) groups of teenagers. His first self-published book was titled The Kids Are Alright (1999), an upfront announcement of his refusal to accept the negative associations of teen subculture, from underage sex, to drugs and parties. Instead, his hazy, lo-fi snaps celebrate the freedom to be found in youthful experimentation.

Celine Sciamma takes a more balanced view in her 2014 film Girlhood, in which a young black girl gang based in the outskirts of Paris grow in confidence through their collective friendship. It is memorably conveyed in a scene in a hotel room where they lip-sync their way through Rihanna’s “Diamonds”. It captures the fleeting escapism that a group can offer from the often difficult reality of teen life.

THE BEDROOM

The teenage bedroom is an inner sanctuary which offers solace in our troubled teenage years. Assailed on all sides by the wilful demands of parents and siblings, the bedroom offers a moment of solitude and privacy within the family house. The use of a door lock to cement this privacy can be considered controversial, so those with their own room often claim their territory in a more creative fashion.

Adrienne Salinger’s series of photographs In My Room, taken in the bedrooms of strangers who she met in malls and through friends in the early 1990s, reveals this act of deliberate personalization; Blu-tacked posters, cluttered surfaces and all. “Teenagers are on the edge of rapid change,” she writes in her introduction. “Their rooms contain all of their possessions, and yet these are the last moments that they will be living in their parents’ homes. The past is cramped together on the same shelf as the future.”

“Assailed on all sides by the wilful demands of parents and siblings, the bedroom offers a moment of solitude and privacy within the family house”

American photographer Charlie White explores this adolescent transformation in The Cyrilla Strothers Project. He worked with the teenage Cyrilla from 2004 to 2007, documenting her life between the ages of sixteen and eighteen. White did not photograph her himself, but placed cameras into her familiar personal environment. Her parents, siblings and friends were asked to take pictures of her on a daily basis, resulting in an archive of more than 10,000 images. The most revealing portraits are taken candidly as she sleeps, while still lifes of details within the bedroom build a portrait of her desires and aspirations as she comes of age.

Jeremy Deller went one step further with Open Bedroom (1993) and actually invited people into his own teenage bedroom while his parents were away, presenting his interior life as art. Joy in People, his 2012 retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in London, mounted an extended reconstruction of that bedroom, filled with Polaroids and band posters. The parental voice lingers in large letters that read “You Treat This Place Like a Hotel”, while “I ♥ Melancholy” stands out in gloss on a black-painted wall, evoking the introspection of teen angst that is as personal as it is universal.

TEEN IDOLS

School notebooks have long been the canvas for teenage outpourings of hopes, fears and, of course, lusty daydreams. Idle fantasies of imagined lovers inevitably alight upon the stars of stage and screen. Glossier, older and so much cooler than fellow schoolmates, they are all charted in impassioned doodles and intricately sketched-out romantic scenes. Of course, no one is immune to the seductive charm of celebrity, but teenage longing is felt in its own extremes, with little room for nuance or reflection.

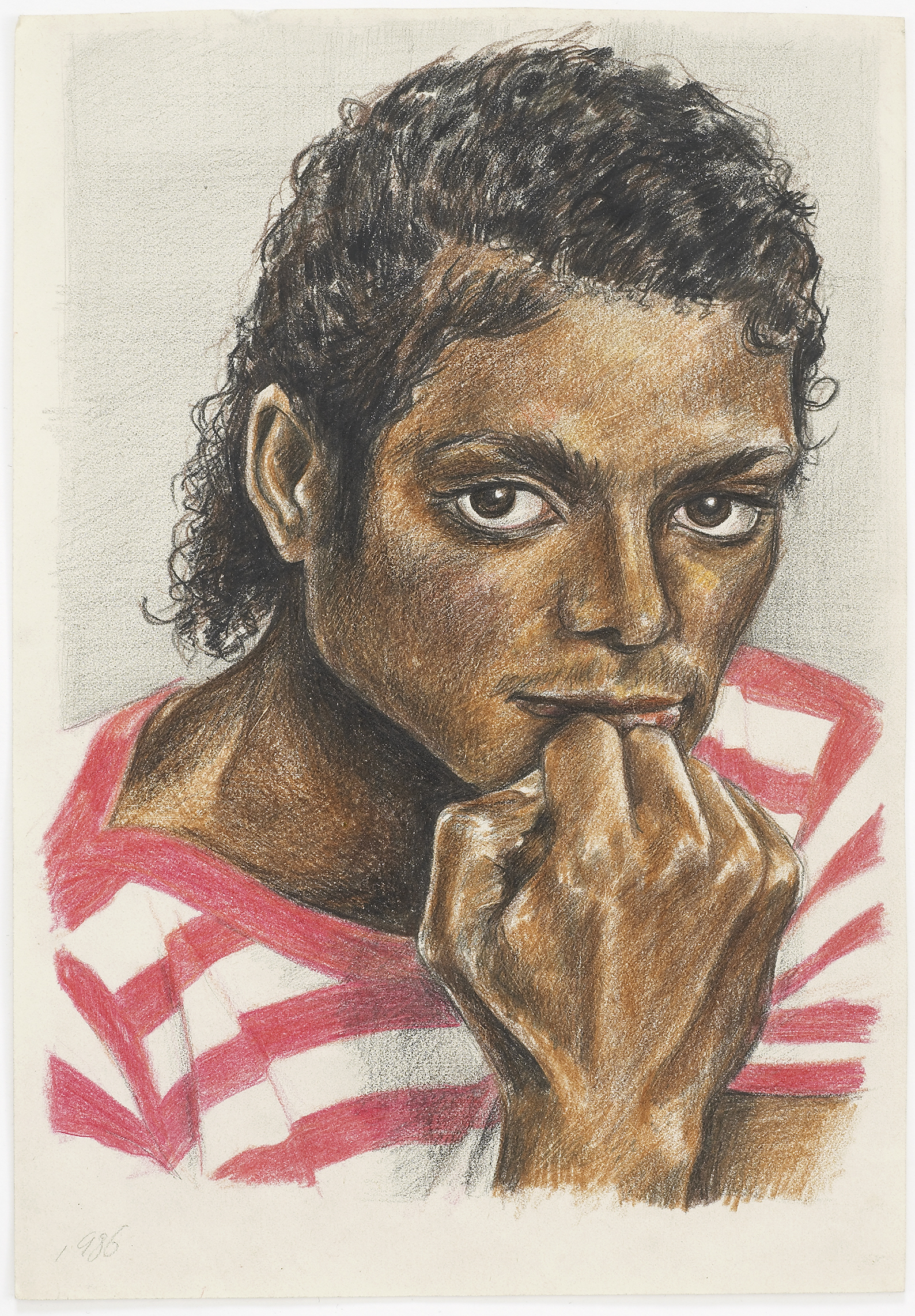

British artist Dawn Mellor knows this well, having spent her adolescent years in Manchester in the 1980s obsessively producing drawings and paintings of Michael Jackson. Drawn in detailed graphite and coloured pencil, they linger upon glamorous press shots, posters and party pictures of the star. A collection of these teenage drawings was published in 2012, as a book titled Michael Jackson and Other Men, which offers an insight into her better-known, often violent and grotesque paintings of figures such as Britney Spears and Judy Garland. As Joe Scotland writes in his introduction, “There is something endearing, and somewhat pathetic, about the Jackson drawings—both as a reminder of a tragic cultural icon and the indication of the burgeoning sexuality and artistic ambition of the young artist.”

“No one is immune to the seductive charm of celebrity, but teenage longing is felt in its own extremes”

Another artist well-known for her fascination with the famous is Elizabeth Peyton, whose intimate, small-scale portraits of rock stars, literary figures and artists conjure the sensuous mystery of the celebrity. John Lydon, Jarvis Cocker, Stephen Malkmus and others are lightly sketched from newspaper clippings and photographs in coloured pencil or watercolour on paper. The blankness of the page can be seen between her tentative strokes, suggestive of that first school notebook of teen crushes. Her tender pictures capture the unattainability of her subjects, even when depicted in unguarded moments, and reveal that this elusiveness is integral to the timeless allure of stardom.

ON THE STREETS

When you’re a teenager, places to socialize can be scarce. You are below the legal drinking age and have little money (beyond parental handouts and Saturday job income), so restaurants, shops, bars and clubs are off-limits, and even trips to the cinema or bowling alley are a rare occurrence. As a result, the streets and other transitory outdoor spaces have always been the teenage stomping ground, and it is not uncommon to see groups gathering in supermarket car parks, bus stops or the entrances to housing estates.

German photographer Tobias Zielony has documented working class juvenile minorities in suburban areas for almost twenty years. His series Car Park (2000), Curfew (2001) and Quartiers Nord (2003), shot in Bristol, Liverpool and Marseilles respectively, follow listless teenagers as they congregate on benches and gather under the artificial glow of street lamps. In one image, a young group crouch beside a makeshift bonfire in a dustbin; disillusioned and disenfranchized, slouched with hands in pockets, they are resigned to their largely invisible status on the margins.

“The streets and other transitory outdoor spaces have always been the teenage stomping ground”

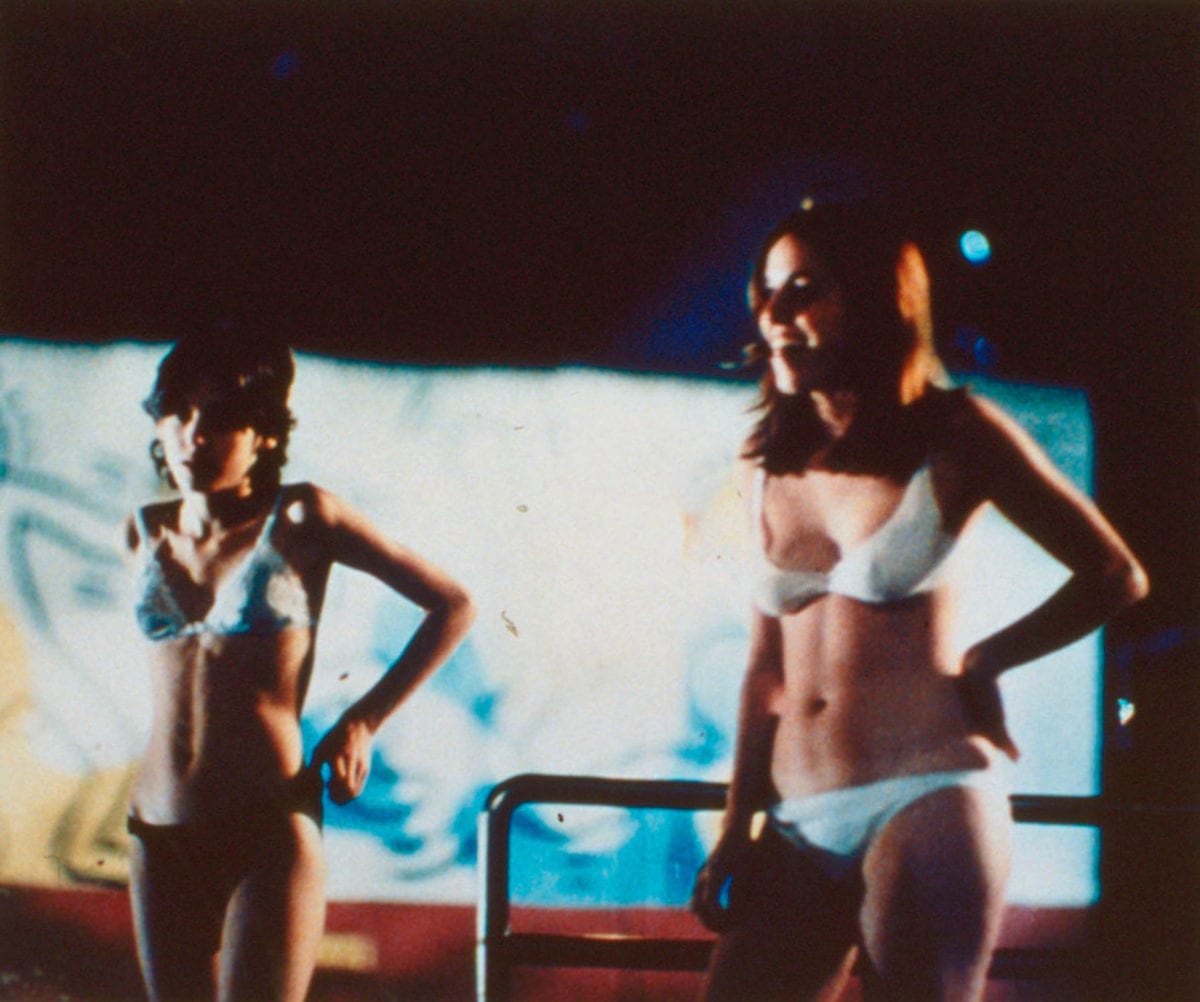

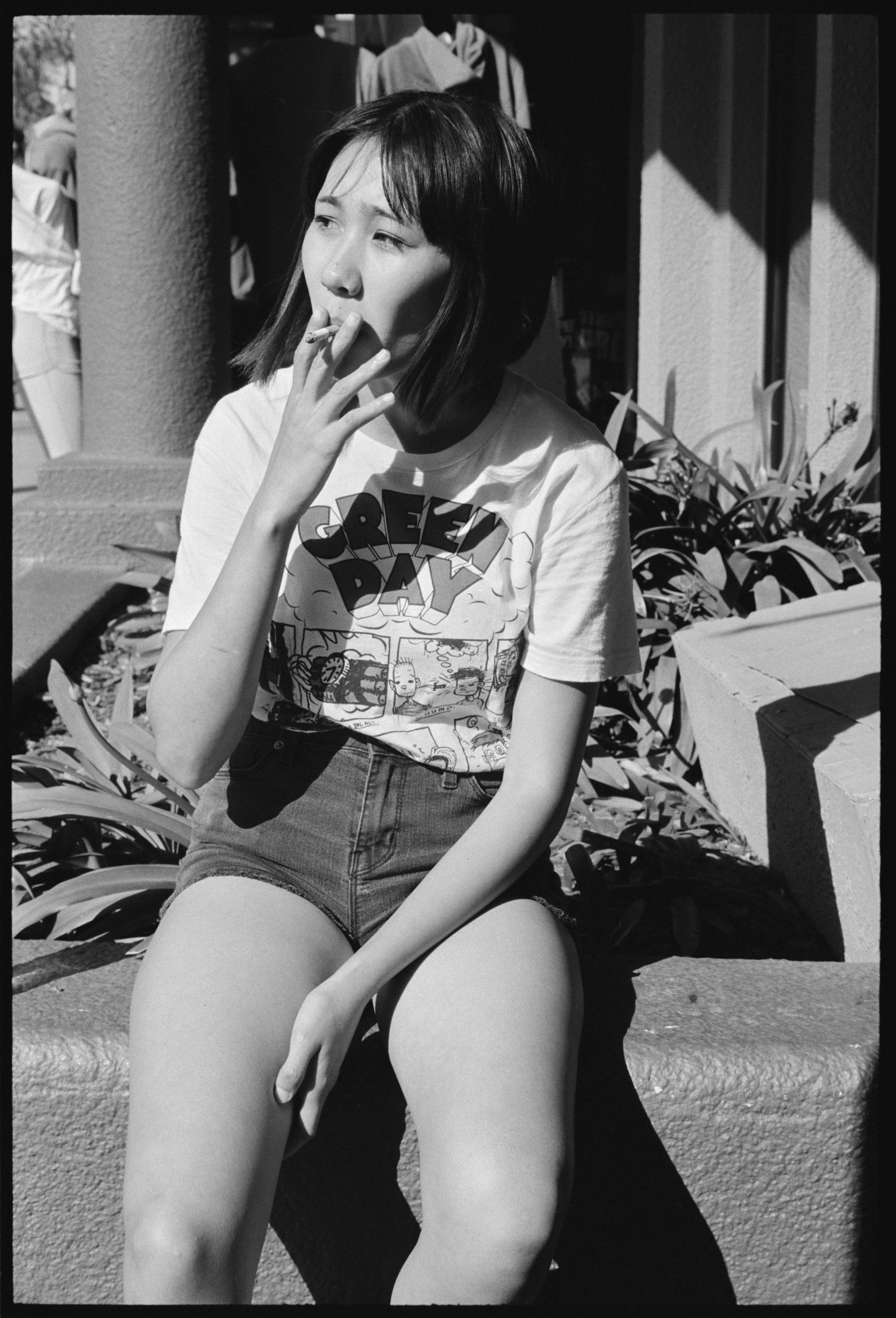

- Both images Larry Clark, Kids, 1994. C-prints from portfolio of 15 © Larry Clark; courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

In his cult photo book Teenage Smokers (1999), Ed Templeton captures some of this frustration, presenting candid portraits of local teenagers lighting up in the skate parks of southern California. Fresh-faced boys and girls inhale with their cheeks sucked in, squinting and smiling at the camera, embodying all the posturing of adolescence. Both Zielony and Templeton critically engage with the inevitable fictions present in documentary photography, as even a casual gesture is made deliberate in front of the camera lens, and the street becomes a stage for these teenagers to strike a pose.

The characters of Kids, Larry Clark and Harmony Korine’s now-iconic 1995 film, also assume personas older than their years. They roam the streets of New York in pursuit of alcohol, drugs and (notably unsafe) sex, with a powerful naivety influenced at least in part by their inexperience as actors: the cast, as well as Clark and Korine, had never worked on a film before. When Jennie, the protagonist, discovers that she is HIV positive, it sets a darker tone that infuses with the wild rebellion of the film. Kids captures the painful realizations of teenage years, as the harsh realities of the world begin to come into focus. The longed-for freedoms of adulthood are revealed to be anything but liberating. Coming of age is shown ultimately to be both a loss and gain, from the pleasures and pains of innocence, to those of experience.

- Both images Larry Clark, Kids, 1994. C-prints from portfolio of 15 © Larry Clark; courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

This feature originally appeared in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 35