Shaquille Heath reflects on Amy Sherald’s mastery and her representation of the Black American experience.

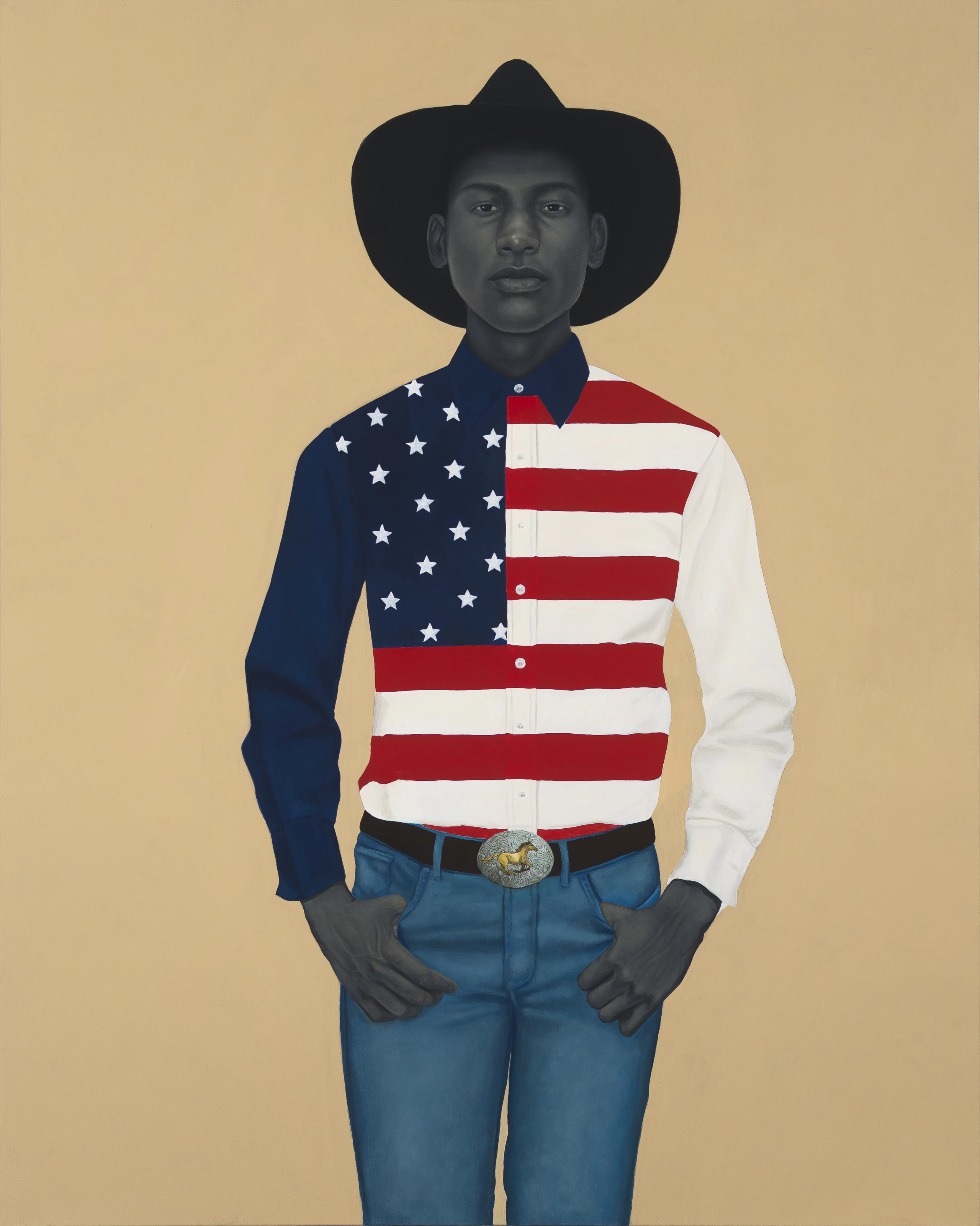

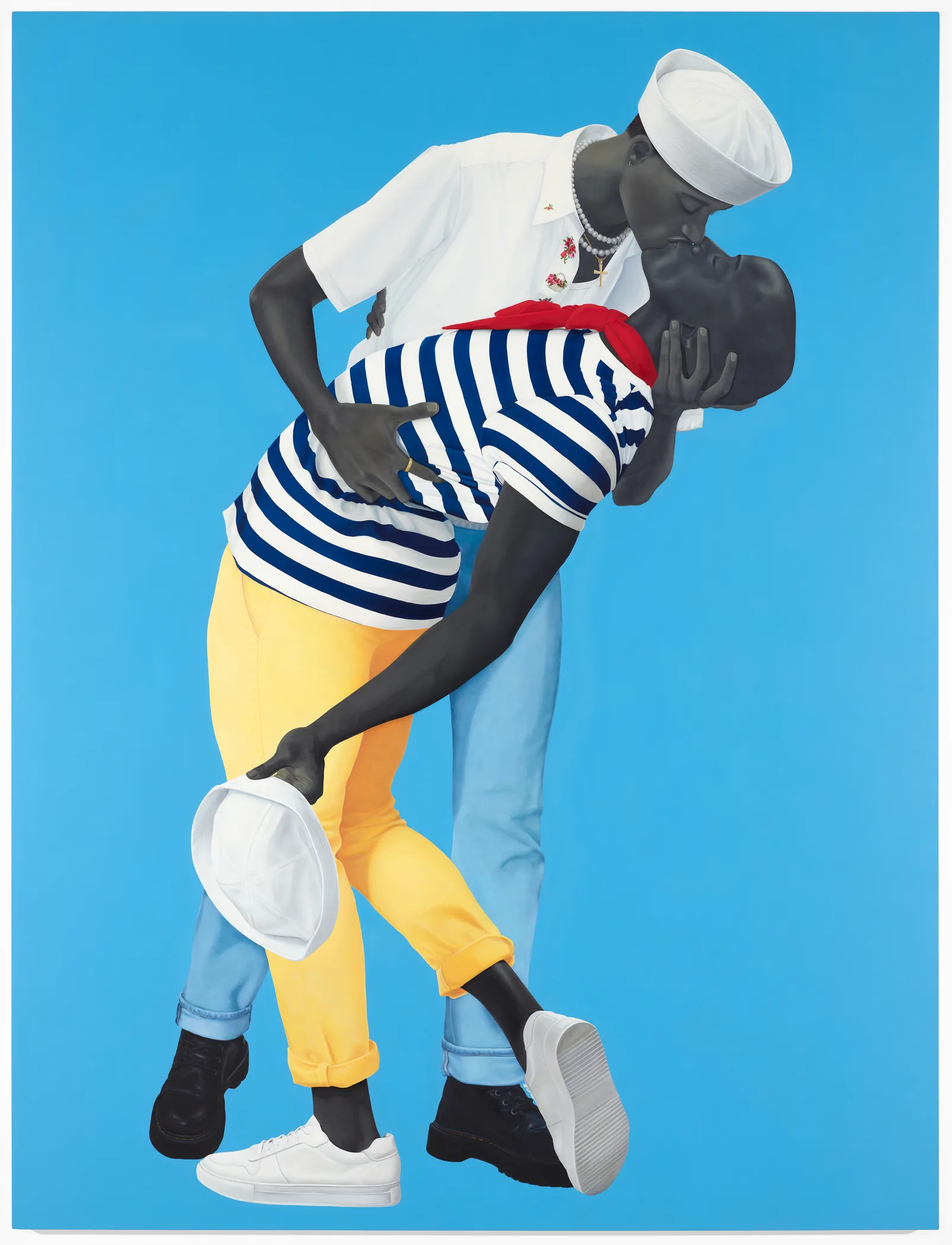

Amy Sherald’s American Sublime opened just 11 days after the U.S. election, in which the American people elected Donald Trump. It is obvious through this exhibition, and of course in Sherald’s work, that the sublime folks that she is referring to are Black folks, and other people of colour — or at least I hope that’s obvious; I’m not a fan of ostentatious art-speak that discusses work in such concrete terms, but this does seem like quite a matter-of-fact truth. That said, it’s an interesting title to give to an exhibition that straddles the line between Black people existing and Black people defiantly thriving, displayed by the spectrum of work on view: Black people doing normal things like swimming at the beach and riding bikes, in contrast to those with scopes of power, such as Michelle Obama’s portrait and the tribute to Breonna Taylor.

Breonna Taylor and I are the same age, both Geminis, our birthdays only 11 days apart — and if you are doing the maths, yes, my birthday is May 25th, the same day George Floyd was murdered. I’ve spent years thinking about the parallels between Taylor and I — how we came into the universe at the same time, how we could have easily switched lives if one of us went left instead of right when we made our way to these physical bodies. How in every moment and every room that someone has the courage to say Black Lives Matter, they are saying it for my life, one that still has a chance to find the beauty in this American sublime.

I use the word “find” for obvious reasons — and again, stay with me. I have deep apprehension about the title of the exhibition, because I can’t honestly say that Blackness and the sublime are linked in the context of American history. I have never been the person you can rely on for positivity, so if that is what you’re looking for, dear reader, you will not find it here. I have lots of positive things to say, but within the framework of Blackness and America… welp.

Trust me, I can rationalise it within the context of this exhibition. Sherald is one of the most beautiful American portraitists that has, and will ever exist — my apologies for the concrete terms, but, again, it’s pretty obvious, isn’t it? I know that Sherald’s work highlights those that are within the everyday — our neighbours, the girl next door, the farmer who grows our food. She elevates them to a place of beauty and power, without the necessity of crowns and swords. Her talent is in the ability to do so without contextual hyperbole.

Starkly outside of this controversial opinion, I have nothing further negative to say about this exhibition. I adore the selected works. It is considered and measured. I love the way the sections have been divided, and the various themes and topics in which the works are grouped. But as much as I love the visual arts, I am ultimately a word person, and I can’t just quietly rave about the exhibition without pinpointing this complexity to me. Sherald is a words person, too — that is why her works have intricate titles such as Mama Has Made the Bread (How Things Are Measured); A Bucket Full of Treasures (Papa Gave Me Sunshine to Put in My Pocket); and For Love, and for Country. She leaves little hints for us here, hoping that we, as an audience, are observant enough to clue in.

A wall text in the “Everyday Americans” section of the exhibition says, “The canvases in this gallery embody Sherald’s central concern — to create images that simultaneously affirm and demand recognition of the full texture of everyday Black life in the United States. This richness has, of course, always been a part of American society, but it has rarely been seen in paintings and museums.” Right there, the exhibition’s curators subtly allude to out the title’s pretence. Everything in Black American society as we know it — all of its richness and abundance — is soaked with the essence of American society. That society is complex, hazardously racist, unabashedly ableist, increasingly sexist, surprisingly homophobic… the list goes on. If I was defining my sublime version of America, it wouldn’t be steeped in the context of all of these things.

“These aren’t passive portraits,” Sherald said in an interview with PBS News Hour. “They are standing there ready to be gazed upon, but also to gaze back at you. And in that interaction I think we should find our humanity in each other.” Sherald wants you to feel the sublime in the everyday American person. But it is a hard moment in history to stand face-to-face with these figures, emitting such bursts of power, when I don’t feel anything but powerless in the face of our America.

And maybe that’s the capacity of this exhibition. That Sherald has created a portal to a different American universe, where everyone can clearly see the grandeur of Black American identity. Staring into the eyes of Sherald’s archetypes is an entirely different arena. Her subjects are imbued with agency, a power to look back at you while you gaze with wonder over Sherald’s techniques. But I want to make space for my belief that Sherald is a bolder painter than just relying upon the mystique of Black beauty. To limit her work to such is quite a degradation to the cleverness of her mastery.

I guess a question that Sherald’s work proffers: is can coexistence actually exist? Is it possible to separate the contemporary moment — the dissolvement of whatever American sublime does exist, particularly by our own democratically elected government — while also spending a day at the beach, finding admiration and awe in the way our skin reflects in the sunlight? Of course it is. We do it every day.

I’ve read that Sherald has been sitting with the title of this exhibition for years. And I imagine, while at least for the months leading up to the show’s opening, there was a bit of hope for the American sublime. We had the possibility of a Black woman as President. Whatever you ultimately think of Kamala, wouldn’t it have meant at least a little something to have her be representative of the American dream, over our current office holder? To me, that would have been lightyears closer to the level of excellence that should exude from such a position — but what a sublime dream that was, after all.

Maybe it is sublime that even through the continued hardships of the Black American experience, you can still take a moment to smell the flowers and drink a sweet tea when the asteroids come barrelling down from the sky. Black Americans have always chosen love in the midst of war. I’m still not convinced it is a sublime way to live — but I sure am in awe of Sherald’s ability to paint it.

Written by Shaquille Heath

Amy Sherald: American Sublime continues at SFMOMA until March 9, 2025, and runs from April 9 to August 10, 2025 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.