Neil Haas and the Act of Looking by Eliel Jones, writer and curator

Speaking to him over Skype, Neil Haas (born 1971 in South Shields, UK) describes his first encounters with representations of male queer identity as being mediated by the page. “Growing up as a teenager in 1980s north-east England nobody talked about being gay […] I lived in secret, like a ghost.” Flicking through books of art history he encountered the likes of David Hockney—whom he professes as his hero—and in literature he turned to Jean Genet. “They depicted and talked about men in a very intimate way. For Hockney they sat naked, often in bedrooms and domestic spaces […] The whole thing was infused with gayness.”

But it was in the spreads of fashion magazines––which Haas perused while a student at an all-boys school––that the artist would later find the types of images of men that have become the subjects of many of his works today. After studying and working as a fashion designer for most of his adult life, Haas recently completed a masters at the Royal College of Art, following his dream of becoming an artist. After a fair stint of exhibitions in the UK and abroad, Haas is currently exhibiting work at The Approach, in London, as part of a two-person show with the late British artist Patrick Procktor.

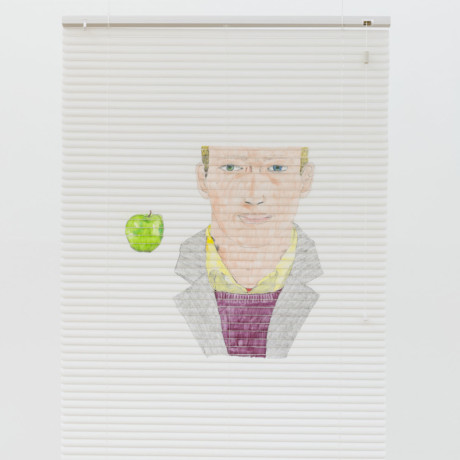

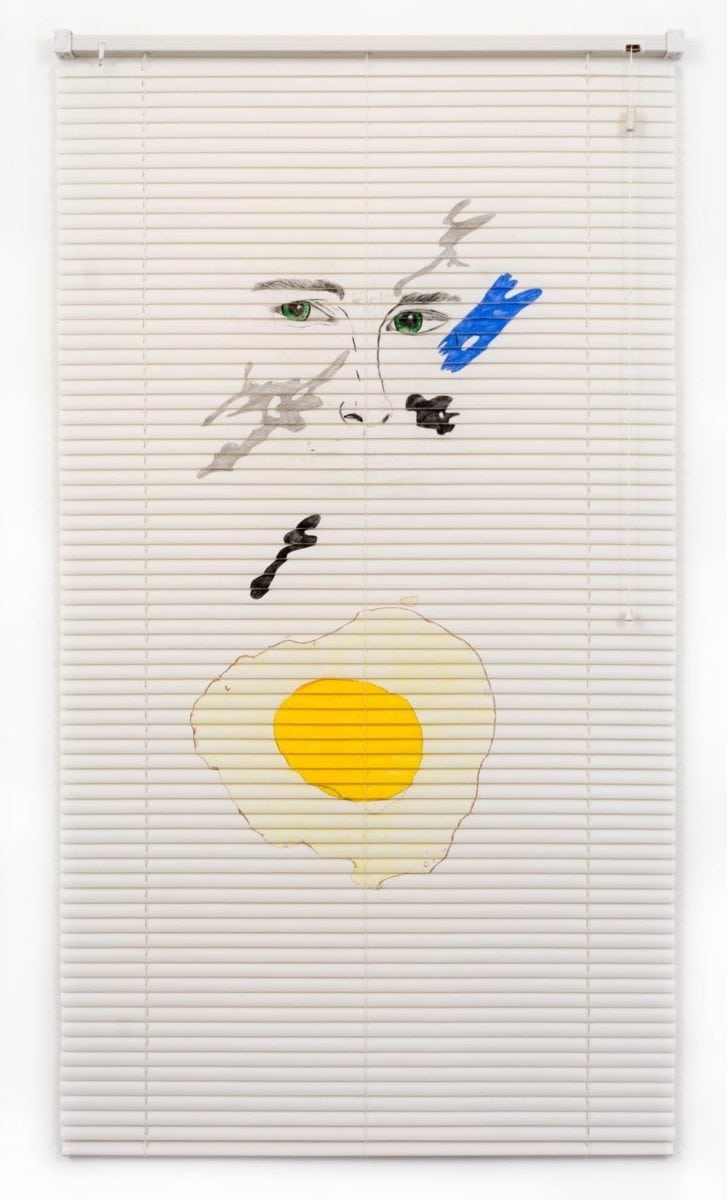

- Neil Haas, In bed, 2018

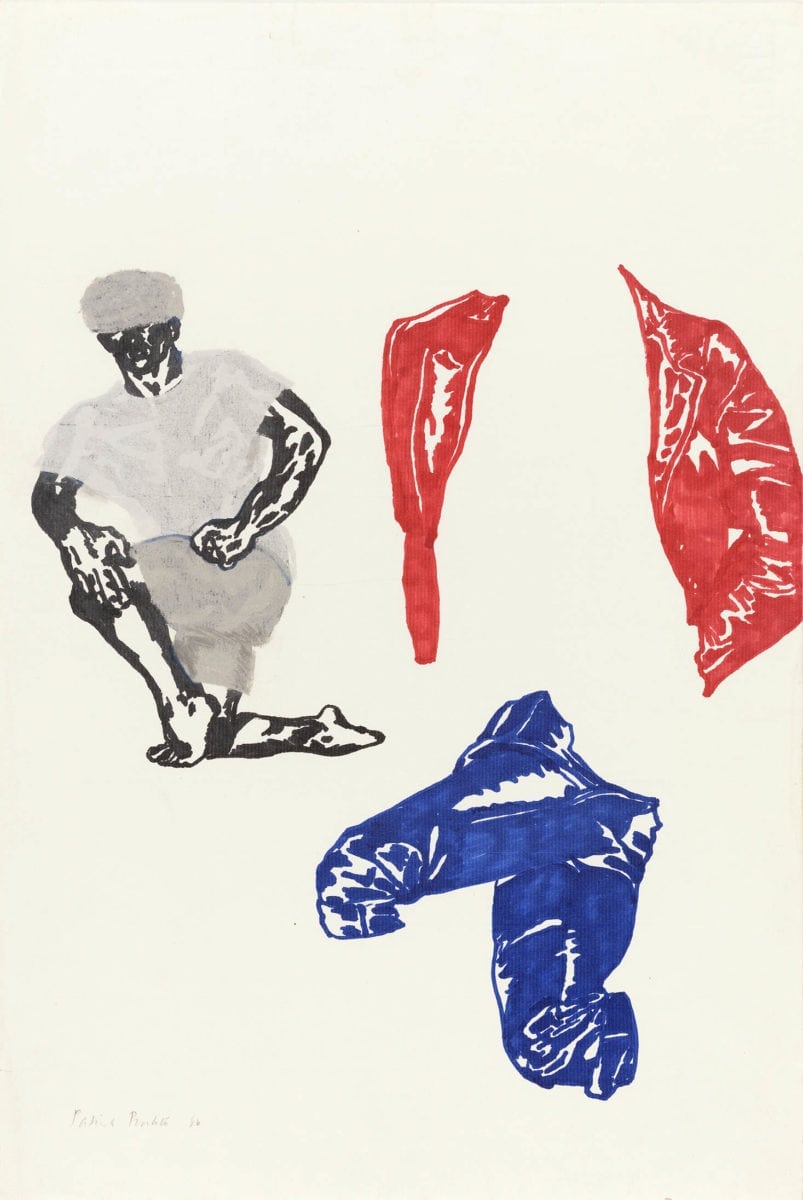

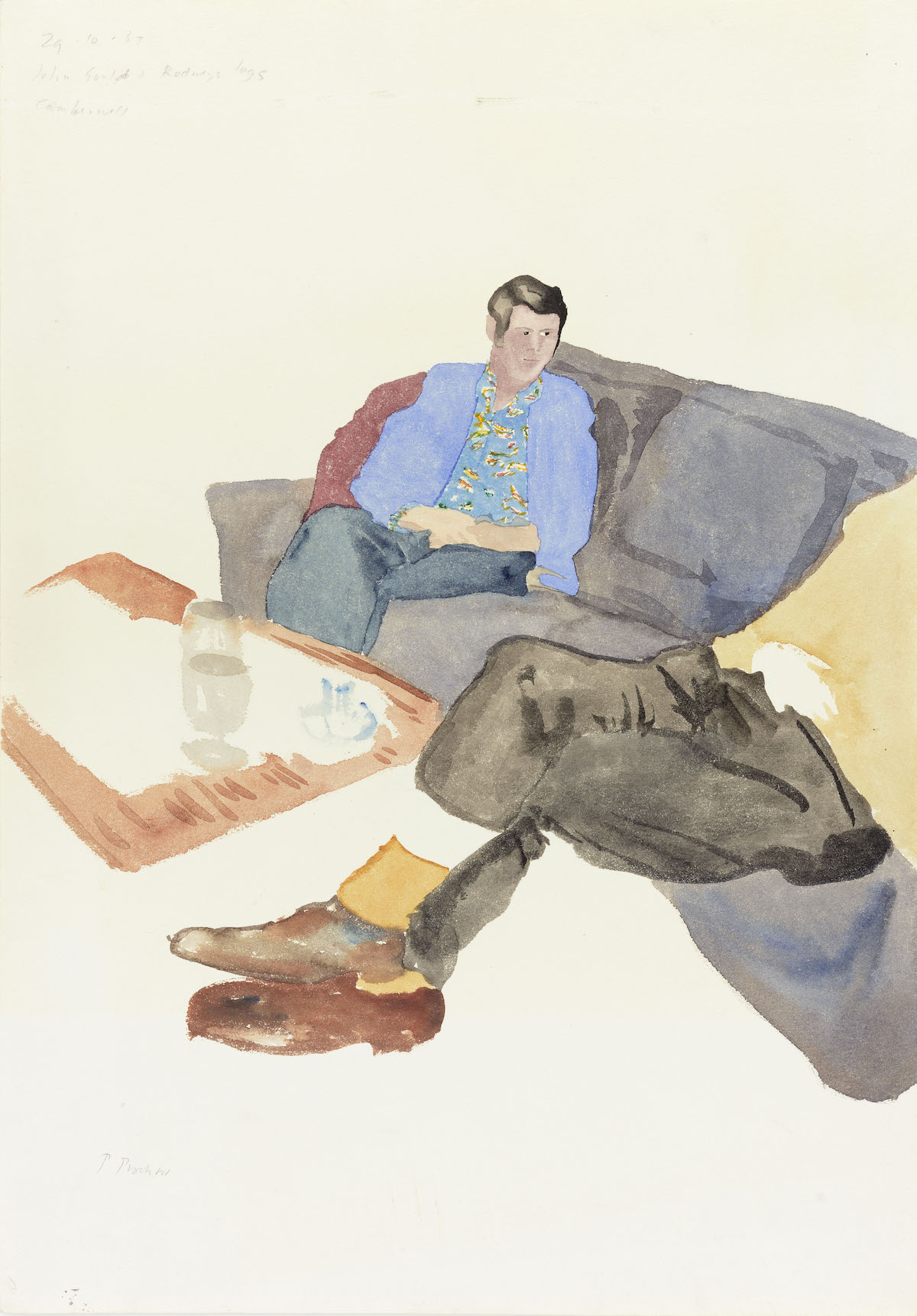

- Patrick Procktor, Untitled (Studies), 1966

“Seemingly unguarded portraits of men place the viewer as a complicit ––albeit simultaneously removed––participant in the act of looking”

Despite the fact that Procktor and Haas dovetail in their desire to look at and picture men, their voyeuristic identities move through different parameters of encounter. While Procktor rendered most of his subjects from live sittings, Haas often removes himself from real life situations and paints mostly from found imagery. The bedroom––both as conceptual form and physical site––recurs as a trope in many of his works; gazing in and out from its windows is a matter of both memory and a projection of desire. Perhaps most clearly representing this is the artist’s signature style of painting directly onto Venetian blinds. Here, seemingly unguarded portraits of men place the viewer as a complicit––albeit simultaneously removed––participant in the act of looking.

Recently the artist has been working with a group of teenage boys on a series of one-off performances that accompany the openings of his exhibitions. At these happenings the young men wear clothing branded with the artist’s name and initials and simply sit around; they smoke, drink and talk amongst themselves and with any daring visitor. In making his name visible and desirable, Haas is reclaiming an agency to his identity. “It feels really good, after the hiding and not having a voice, to just say my name.”

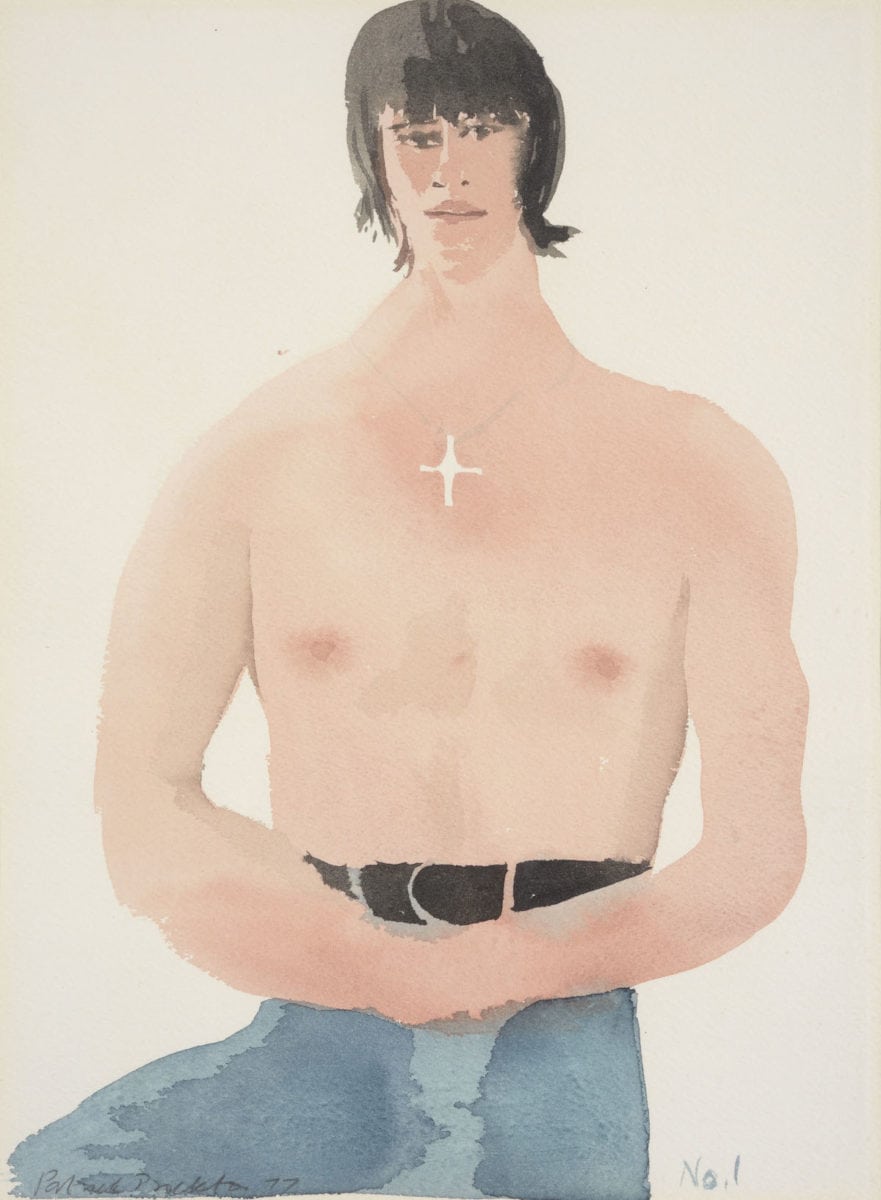

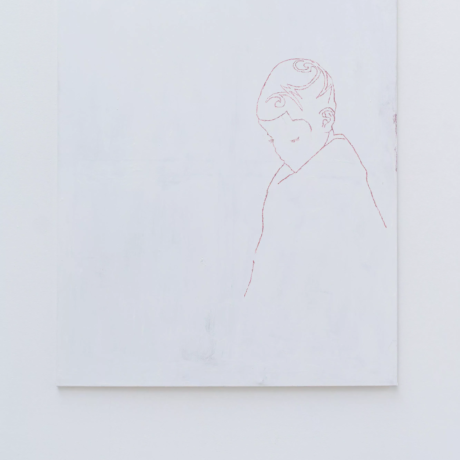

- Patrick Procktor, Marius, 1977

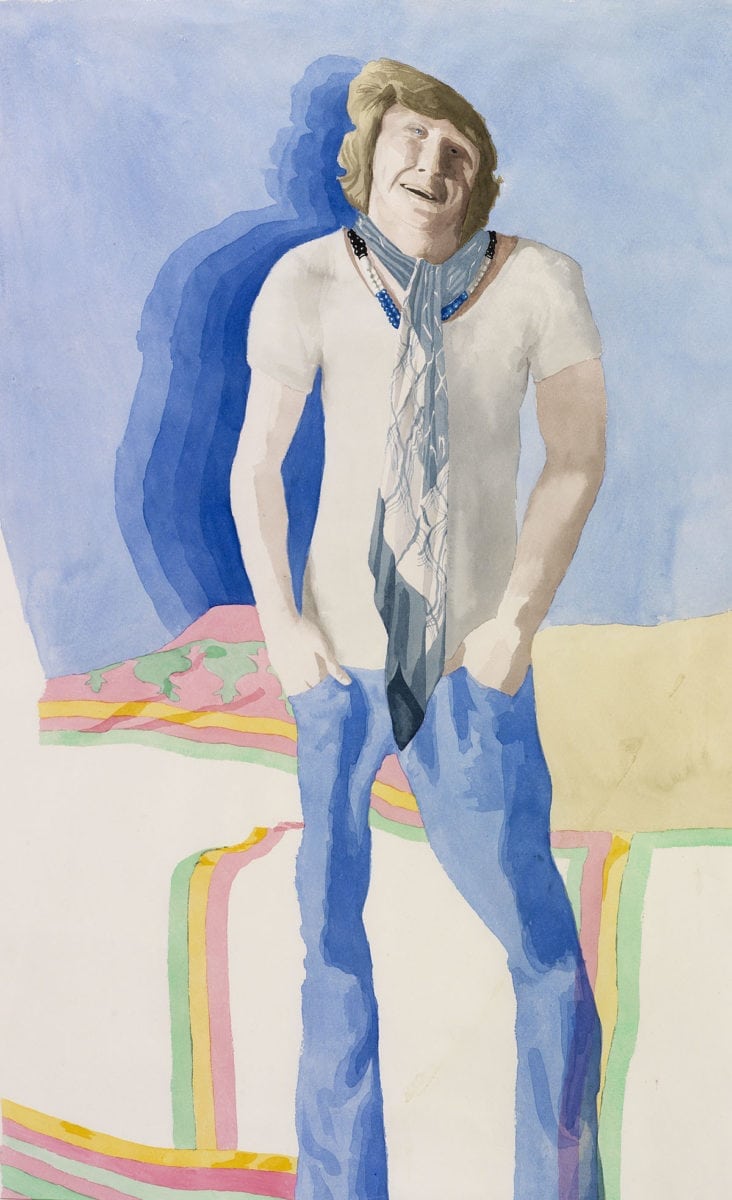

- Patrick Procktor, Nicol Williamson, 1977

Patrick Procktor’s Understated Painterly Language by Ian Massey, art historian, curator and author of Patrick Procktor: Art and Life (2010)

Patrick Procktor RA (1936-2003) is a key figure within the legendary set that epitomizes the bohemian glamour of sixties London, a set that also includes his great friends the artist David Hockney and fashion designer Ossie Clark. A star student at the Slade School of Fine Art, he graduated in 1962, and less than a year later held his first exhibition, at the Redfern Gallery in Mayfair. A near sell-out, it opened to huge critical acclaim in May 1963, immediately making Procktor one of the most sought-after artists on the contemporary scene.

Along with his obvious talent, he was fiercely intelligent and, at six–foot–five, physically imposing. He was also a charismatic dandy, renowned for his Wildean theatricality and wit, very much at home within the heady milieu of art, theatre, fashion and rock music that he inhabited. The subjects of his watercolour portraits of the sixties and early seventies—often painted from life in Procktor’s Marylebone flat—are mostly from this world, taken from the artist’s wide circle of friends and acquaintances. Many are gay, and include both establishment figures and those associated with the counterculture. Some are famous, whilst others are footnotes within the period’s histories.

“Taken together the portraits serve as a social document, of an era in which accepted norms of behaviour, sexual and otherwise, were jettisoned in a new age of social freedoms”

Procktor first took up watercolour seriously in the summer of 1967, finding it ideal in translating the transient effects of light and colour that so beguiled him, and gradually achieving great mastery in the medium. He very rarely made any preliminary drawings, but instead began with washes put down with a fully loaded brush, in a carefully judged process involving great fluency and lightness of touch. In a telling phrase, the artist John Craxton described Procktor’s gift as that of “the chic of facility”. His portraits arise from a highly idiosyncratic brand of stylised artifice, in which extraneous detail is often edited out, the figure carefully poised within the white space of the paper. The subject is often depicted with some kind of distortion, of limbs and/or visage—in results that are both mannerist and psychologically acute.

Taken together the portraits serve as a social document, of an era in which accepted norms of behaviour, sexual and otherwise, were jettisoned in a new age of social freedoms. The revolution didn’t last, but reverberates still: as does Procktor’s understated painterly language, which now looks conspicuously relevant, wholly at one with much of what contemporary figurative painters seek to emulate.

- Patrick Procktor, Christopher Gibbs, 1967

- Neil Haas, Breakfast choices, 2018

Patrick Procktor, Tender and True by Louise Benson, deputy editor of Elephant

For years I knew Patrick Procktor the man, rather than Procktor the artist. As the step-father of my dad since childhood, he became my only paternal grandfather, and his loud, flamboyant and at-times demanding presence would come and go in my life as I grew up. I remember the fabulous, decadent interior of his home, where custom-made caryatids held up a marble fireplace and heavy velvet curtains draped on to worn sofas, filled with the heavy smoke of the cigarettes he lit up endlessly. Lunches would be long, and I rarely understood his wry jokes or performative manners. Famous friends and artist names mean nothing to a child, and I paid little attention to the circles that he moved in or the wild stories he would tell.

Years later, I have found myself returning to these memories, as I encounter Procktor’s work from a new perspective. His portraits are honest reflections of everyday encounters, and seem to carry with them the pleasure of casual conversation between friends or lovers, intimate in their immediacy. Most were done at home, where he enjoyed receiving guests freely, and the markers of that easy welcome—a glass tumbler of water, an extra cushion, a wine glass—are present in his paintings.

“Far from acting as a time-capsule, his watercolours from the sixties and seventies resonate with our modern-day documentation of life in the digital age”

He offers a non-hierarchical way of seeing, and surprising details that others might instinctively choose to omit are left in—stark for their selection amidst the white of the page. One of my favourite paintings by him, which he gave to me soon before he died, shows a punnet of supermarket peaches, unwrapped and still covered in ugly red protective netting. Likewise, the focus of an early work, John Gould and Rodney’s Legs (1965), inevitably becomes the mustard sock in the foreground. In choosing to include these contemporary markers, his paintings become truer to life.

Far from acting as a time-capsule, his watercolours from the sixties and seventies resonate with our modern-day documentation of life in the digital age, when social media updates will capture anything from a quiet dinner to a late-night drink. It is also intriguing to observe how Procktor’s own paintings now circulate online, garnering hundreds of likes on Instagram. His pairing with Haas at The Approach feels timely and important, and reflects the two artists’ shared, highly contemporary interest in the personal psychology of their immediate surroundings. I realise now that for Procktor, the grandfather who I grew up with, there was no separation between art and life. The home that I used to visit was his studio—at the dining table, on the sofa, in the hallway—and what I remember of him can be found by all who look at his paintings, as tender as they are true.

Images courtesy The Approach, London and The Redfern Gallery, London. Photographs by Damian Griffiths