In a tall-ceilinged dining room in an airy Berlin apartment is a rail hung with multicoloured shirts—each similar in shape, yet curiously different from the others. Waves of green and white grace one, followed by a flash of zig-zagging red, followed by another dotted with lime green threads. What each of these vibrant sleeves have in common is that they are punctuated by an impeccably cut cuff, making its final statement like an exclamation point.

The designer stands in front of the rack, gently removing the shirts from their hangers and modelling them one by one. When the fabrics are draped over his body and set against his dramatic white beard, their wonders are instantly revealed. Inspecting a shirt made out of a patchwork of striped blue rectangles, my eyes dart to try to make sense of the irregular patterns, but never quite find respite. New worlds seem to emerge from these broken arrangements. I learn that the shirt has been constructed by sewing together nearly 100 different rectangles, which are then wrapped to form a whole, rather than front and back panels sewn together with a side seam, which is how a shirt is traditionally made.

“A sense of wonder is important to me—I want people to stay in that moment of perceiving, of being open, and not judging,” says the shirts’ designer (and model) Mark Jan Krayenhoff van de Leur. To prolong that moment of optical suspense, the designer rarely allows patterns to repeat in his work. “Once you ‘get’ an idea, you’re no longer perceiving or experiencing it anymore,” he explains.

“His philosophy stems from architectural thinking: a drive for the tectonic, for organic wholeness, and for total formal integration”

Mark is self-taught in all things sewing; originally from Canada, he only began creating his conceptual couture after emigrating to the German capital in 2013. Before that, Mark and his husband—the artist AA Bronson—had been living together in New York City for many years, and Mark practised his long-term profession of architecture, trained in the 1970s following the modernist dictum of “form follows function”.

In Manhattan, he worked primarily on apartment renovations (Lou Reed referred to him as the “Markitect” after he’d finished the musician’s office). And while Bronson was director of the legendary artists’ bookstore Printed Matter, Mark designed the interior, including its fluid, shapeshifting shop counter—a steel, plexiglass, and bright orange construction of sharp lines and organic edges. Like the patchwork shirt, no part of its neon surface repeats itself, continually drawing the eye across its complexity. And also like the shirt, it lays bare its own construction process—reflecting a modernist ethos while twisting it into the personal and idiosyncratic.

“When the fabrics are draped over his body and set against his dramatic white beard, their wonders are instantly revealed”

Highly systematic and rule-driven, Mark’s practise as a clothing designer is inextricably bound to his training as an architect. His shirt patterns first take shape through AutoCAD—the architecture software he’s been using for over twenty years. Manipulating line and volume as if he were constructing an interior, his philosophy also stems from a kind of architectural thinking: from a drive for the tectonic, for organic wholeness, and for total formal integration.

“Being an architect was a good job for me, it was a pretty good fit. And really, the only downside to it was that, for the most part, you’re working for clients and you have to suit their taste, and most of my clients have more conservative tastes than I do,” he says. Shifting his vision to cotton, buttons, threads, leather, wool and ties opened up new possibilities of unrestricted, pattern-seeking play.

Growing up with a love for fashion, Mark always had a vague sense he’d perhaps one day make clothes. It wasn’t until his husband’s year-long Berlin residency, and Mark’s own corresponding break from work, that he found the space to try his hand. Unexpectedly, both the relocation and the medium change became enduring ones. “I didn’t know whether the shirts would lead anywhere, but here I am, six years later,” says Mark in his dining room of intricate wooden furniture where his garments are currently displayed.

Years of idle musing—looking at clothes and imagining them as something else—and an examination of his own wardrobe became points of critical departure, so it wasn’t long before his architectural intuition located a structural problem of sorts. “If you look at a normal shirt pattern, the pieces relate to each other functionally but there is no aesthetic or formal relationship between them—between a sleeve and a body panel, for instance,” he says. Mark then made this discrepancy a central concern and engine of his experimentation: learning through looking, then learning by doing, all the while aided by YouTube tutorials and one “very simple” sewing machine.

“My ideas are maybe not the most practical, but they are really a different way of solving the problem”

Each of Mark’s garments begins with one core concept, although the outcomes are anything but simple. In his dining room, he models a forest green shirt speckled with orange threads that seem to glow from the deep fabric like constellations. The design was driven by a guiding question: how do you make a shirt’s body from one piece?

The body is indeed one rectangle of fabric, as are the two sleeves: to produce the garment’s shape, Mark scrunched the material into wrinkles, and then sewed those wrinkles into place with the orange thread. “You can see, if you start here, it’s just one piece. And also, the body is one piece. There’s no side seams,” he says, turning to show me. He holds up his arm: while a normal sleeve is tapered from the shoulder to the wrist, here the sleeve is a cylinder of the same width all the way down to his hand—but it’s been scrunched to create the cone shape, with the wrinkles dramatised by the fluorescent thread, literally highlighting the making process itself. One simple idea, but a complex, visually distinctive outcome.

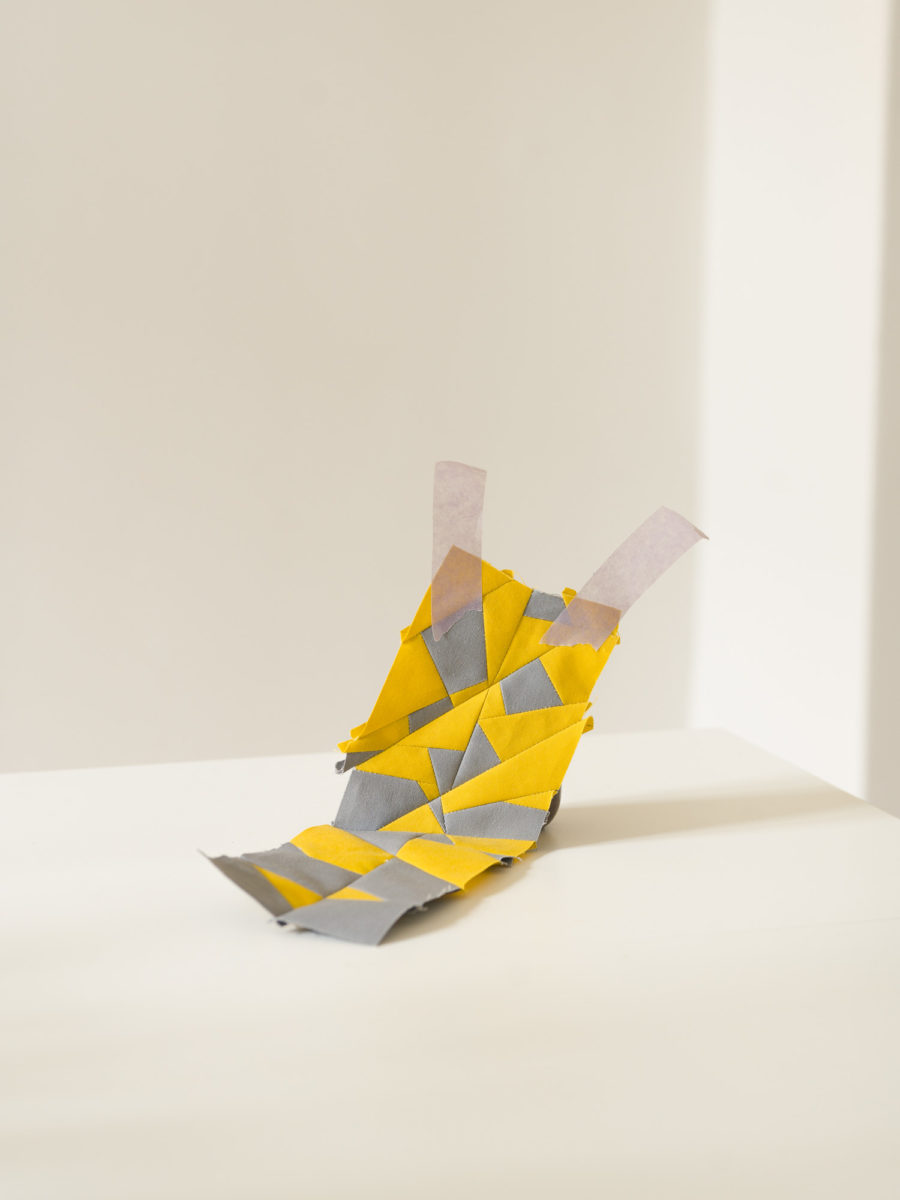

“My ideas are maybe not the most practical, but they are really a different way of solving the problem,” Mark says, referring to his often puzzling and lengthy processes. He credits the mediums, minds and material manipulation of Japanese pioneers Comme des Garçons, Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake for shaping his approach—one committed to the simple idea that garments take their forms through flat pieces of cloth. This formal sensibility also encouraged Mark to design jackets, t-shirts, vests, and knitwear, adapting to their distinct shapes and challenges. He holds one jersey tee to the light, which features a bold array of red hand stitching. It’s been made from one continuous and elegant spiral of fabric, energetically sewn together using one emphatic thread.

Next is a tank top made of a patchwork of Etsy crochet finds—there’s square motifs, doilies, hand sewn bookmarks, and a few 1:12 dollhouse blankets—carefully assembled to take a vest form. Seen in this arrangement, the most mundane (and often culturally trivialised) craft medium takes on newfound beauty. He then models a green, blue, and white dotted coat; the concept for this one was to construct its shape lengthwise from vertical slices of alternating stripes.

“I solve so many problems and I design so many things in that dreamy, half-awake state”

All of this highlights a particular strength of Mark’s: to rethink the most fundamental things, be it a doily or the basic cut and shape of a garment, and to turn them entirely on their heads, always without the result appearing too studied. “Whenever I hear, ‘It’s always been done this way, or has to be done this way,’ I know it’s fertile territory,” he says. “Why does it have to be done that way?”

This open questioning of norms, commitment to materials, and holistic thinking combines to form Mark’s singular queering of modernism, at once true to its egalitarian mission and resistant to prescription. Like the architectural giants he studied years ago, the decorative quality of his design emerges out of a deeply systematic approach, rather than something applied on the surface. Patterns and abstract forms offer a kind of freedom to experiment and for Mark, it’s important that nothing is hidden—hence the bold threads to highlight seams, or the vibrant patterns that emphasise the shapes underlying a garment’s construction. It’s a motivation he sees connected to “being a gay man, being queer, and so wanting to let everything be what it is and be the best of what it is naturally.”

The dining room of Mark’s apartment leads, in a wonderfully open, wrap-around style, to his and AA’s studio. On one huge surface stand stacks of books, and, in Mark’s section of the room, a table overflows with fabric samples, chunky knitwear, bright threads, and tangles of wool. It’s a light-flooded room brimming with ideas from every direction. It’s easy to imagine the designer working here, structuring his thought patterns, though he tells me that it’s actually in the early hours of the morning and during the hush of night—in nightgown and slippers—that he finds his ideas take their shape. As he gets older, Mark sleeps less, yet finds new use for this liminal time. “Your brain is in a different frame of mind, and all my great ideas come then,” he says. “I solve so many problems and I design so many things in that dreamy, half-awake state.”

Making, stitching, constructing, designing, wearing—these acts have the power to make fashion an intensely personal undertaking, one that goes far beyond trends and labels into something more meaningful, serious, and self-defining. For Mark, coming to terms with his own identity was a challenging process, involving a difficult youth of repressed feelings and a long path to self-acceptance. And now, years later, he still finds an expression of this process deeply informing his making.

“It’s where the whole drive towards wholeness and integration comes from, too. It’s from not feeling whole,” he says, wearing his lavender and poppy-red striped shirt. Constructed by delicately sewing together and overlaying stripes of the two fabrics, the design is unique, formally complete, and entirely perfect: beautiful because of its form, a form that queers the norms of construction, and which looks the way it does by keeping true to its guiding principle.

All photographs by Rick Pushinsky from the book MJKVDL 2021. This essay is republished with permission from MJKVDL 2021 © Chateau International 2021