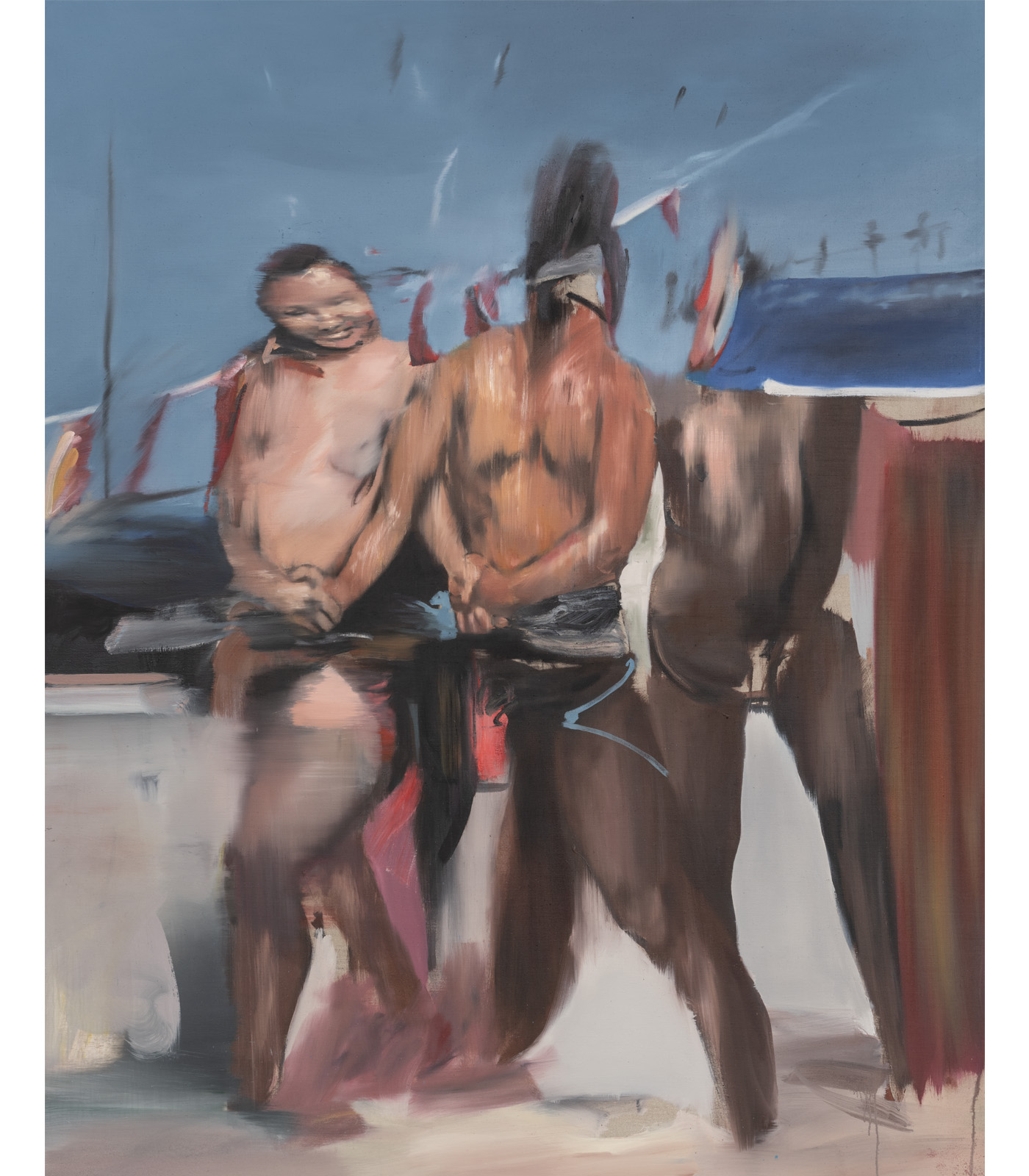

George Rouy is a fantastic painter, I think. I’m standing in front of Trauma Bond (2024), a work of his that depicts three figures in a row, their indistinct legs overlapping and blurred hands interlocked. They stand against a slate blue sky, feet sinking into the clay-coloured ground. Two faces are completely obscured and the third is distorted, as though squeegeed, Gerhard Richter-style, before it had a chance to dry. Its frenetic, dramatic strokes make me think it was painted quickly, by someone guided by the kind of rare intuition that only a great artist has. Yes, I think: George Rouy is going places, this is a painting that you can get lost in.

But I’m not really in the mood to get lost this afternoon. A painting can, like Rouy’s, be a beautiful, troubling, thought-provoking thing. Art can be transportive; you can get lost in it. But it is also subject to a market — the biggest unregulated one in the world, aside from illegal drugs — and, as in all markets, there are winners and losers. As I walk around Present Tense, the current exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, I am busy wondering about how a show like this one contributes to that dynamic.

I may not be lost, but I am not near home either. Hauser & Wirth Somerset is set on Durslade Farm in the well-heeled village of Bruton. Present Tense features 23 artists, none currently represented by Hauser, and claims to showcase “the next generation of artists living and working in the UK”. I first read about the gallery in Boom, a book by American journalist Michael Shnayerson about the art world’s most powerful dealers. In the book, Iwan Wirth, one of the gallery’s directors, describes himself and his wife and co-founder Manuela as “the art farmers.” If Hauser is an art farm, these artists are saplings with every chance of one day yielding a good crop.

But who gets to do the harvesting? Some of the country’s hottest emerging artists — or as spittle, my favourite plain-talking art world newsletter, puts it, “pretty much all the painters coming to commercial/Instagram prominence from the lockdown period to the present” — are here. Twelve of their galleries are too, listed as collaborators on the exhibition. Most are small operations based in London and my guess is that, for them, a show like this is a mixed blessing. In her review for the Guardian, Hettie Judah imagines that their experience “has a swimming-with-sharks quality,” Hauser being a formidable partner that might just also be a predator.

In art, like in any creative field that involves talent and representation, said talent is liable to outgrow said representation, upgrading to a new representative — in this case, a better-established gallery — that can offer new opportunities. Within this dynamic, Hauser sits at the top. It has museum-scale spaces, links to institutional collectors, an in-house publishing company and residency sites around the world. If there’s something that they don’t offer their artists, it’s probably not something that many artists want.

I first saw Rouy’s work six years ago. I was new to the art world, and still wrapping my head around the Wild West economy that I had read about in Boom. I was also new to London, and keen to visit Hannah Barry Gallery, a space I had heard about a short walk from my flat. The eponymous Hannah is a stalwart of London’s emerging art scene. As well as Bold Tendencies, a not-for-profit public sculpture programme based on the roof of Peckham’s Bussey Building, she runs the gallery, which has been in business for more than sixteen years. Here, I saw Rouy’s solo exhibition Squeeze Hard Enough It Might Just Pop!.

When Barry first showed his work, Rouy was a promising recent graduate. He was painting differently — his figures blobbier, rendered in less naturalistic shades of pink and blue and with more precision — and he wasn’t yet enjoying the level of recognition that he does today. He has since been the subject of museum exhibitions, and shows regularly with Almine Rech, a major French gallery with locations around the world. Luckily, he still seems to have paintings for Barry— his last solo exhibition at her Peckham gallery was just last year.

The artist-gallerist relationship is vaguely defined and ‘representation’ is a slippery term. Exclusive contracts are rarely signed, meaning that an artist might be represented by multiple galleries at once; or be represented by nobody, making a decision on each opportunity as it comes up. An outcome of this is that they can, like Rouy, climb the ranks of the art world without leaving their early backers in the dust. But there is no guarantee of this. Making work takes time, and an invitation to show with Hauser, with all of its attendant opportunities, might outweigh an artist’s sense of loyalty to the gallerists who first nurtured them.

Who can blame them? In many ways, the grass is greener on the other side. Allison Katz, one of my favourite painters, had a great year in 2022: her witty solo exhibition Artery opened at Camden Art Centre, her work was included in the 59th Venice Biennale and, perhaps inevitably, late that summer, she announced new representation with Hauser & Wirth. She stayed with three of the small galleries that represented her around the world, but left behind her New York gallery, Luhring Augustine. With the art farm calling, something had to give. So far, she has been rewarded with a residency on Durslade Farm and a solo exhibition at the gallery’s 6,000 square-foot West Hollywood space.

I find the shark-infested-waters analogy for the art ecosystem very tempting. I imagine the Hausers of the world threatening to tear an artist away from their existing gallery like a limb from a swimmer. The reality, though, is different. Unlike limbs, artists have agency. They are not an extension of the galleries that showed them early support, and they certainly don’t belong to them. Furthermore, Hauser doesn’t necessarily want to completely sever its new artists’ relationships with their existing galleries. Last year, it announced a new model for collective representation with small galleries which, though its exact details remain fuzzy, promises to involve “intensive resource sharing”. If executed properly, and if executed in good faith — two big ifs — such a model could replace david-and-goliath competition between galleries with joint efforts to serve artists better.

My amateur market punditry might have led me to lose sight of the most important part of the system: the artists and their work. When I speak with Isabella Bornholt, the Associate Director at Hauser who curated Present Tense, she is interested in talking about the pictures on the walls. She’s excited by what she calls a “return to skill” in the show: the artists are all conceptually rigorous, but they also know how to paint. Asked who my favourite one in the exhibition is, I tell her that, for just that reason, it’s Rouy. “It truly came from a place of wanting to give these artists a platform,” she tells me, and I leave the call feeling like I have been overly paranoid about her intentions.

Who should the art world function for, anyway? In focusing on the imagined plight of small gallery owners, I hadn’t considered how wonderful this platform must be for the 23 artists selected, and how exciting the prospect of joining Hauser’s roster might be for them. And what about the public? Durslade Farm receives thousands of visitors each month, many of whom will likely never visit an independent London gallery — isn’t it a good thing that some of the best art coming out of the UK is somewhere that people will see it?

“There is definitely an important place for small and midsize galleries. But they will need to be very smart business people, which a lot of them are not,” Marc Payot, another of Hauser’s presidents said in an interview in 2019. He’s speaking from his place in the winners-and-losers dynamic that preoccupied me during my visit to Bruton. The subtext is clear: if you’re not smart, you might lose your best artist to his gallery.

Maybe that’s the beauty of this world: It’s a free market where brilliance is rewarded. Or maybe it’s just a fact of life. As a gallerist, surrounded by competition, you can’t expect to rest on your laurels— a reality that Hannah Barry is aware of. Asked in an interview how the arts landscape has changed since she opened her gallery, she said “one starts in a moment of change and progress, and continues on in a moment of change and progress.” This attitude might be what has helped her to keep Rouy on her roster.

Ye Wenjie, a character in Cixin Liu’s novel The Three Body Problem, wonders about the relationship between humanity and evil. Is it a necessary aspect of being human, baked into us, or something that we might cleanse ourselves of? She decides on the former: “it was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair.”

I don’t think that evil is an intrinsic part of the art world but I do think that the type of competition I have been talking about is inevitable. It’s part of the gallery system’s DNA, just as Ye thinks that evil is part of ours. Good or bad, the brilliant artists will gravitate towards the biggest galleries. That’s just how the ecosystem is structured.

I’m still not sure whether this should be celebrated as a reward for the best artists and gallerists (perhaps the “smart business people”) or criticised as a vampiric outcome of an unregulated marketplace. But I am sure that it isn’t going anywhere, so I may as well try my best to enjoy the paintings.

Written by Phin Jennings