As Philip Zimbardo writes in his book, Man Disconnected, the many factors of contemporary society are now causing a worldwide modern meltdown of manhood. Japan is no stranger to this phenomenon. With the threat of North Korea, earthquake, political corruption, continuous re-operations of the nuclear power plants, etc., it’s a miracle that anybody is even able to maintain sanity on this small island. But on top of that, men and boys are constantly under pressure to “act manly” in this country that ranked 111th out of the 144 countries in terms of gender equality (according to WEF’s Global Gender Gap Report 2016). Women and girls must suffer from having gender stereotypes imposed on them. Yet signs are everywhere that things are approaching a limit.

Observing the current gender roles of Japanese society, there is definitely an imbalance in between sociocultural expectations and what the actual people can provide. Men are at a standstill, and many are becoming either extremely passive and introverted, or blindly and relentlessly selfish and violent, and a surprising majority of the women are silent and succumb to social pressure. Reconstruction of social values and gender roles are indispensable for both men and women now, and we’re lucky to have an exhibit that can inspire us to seek out a new form of gender balance for our time, all the way from the early 20th Century.

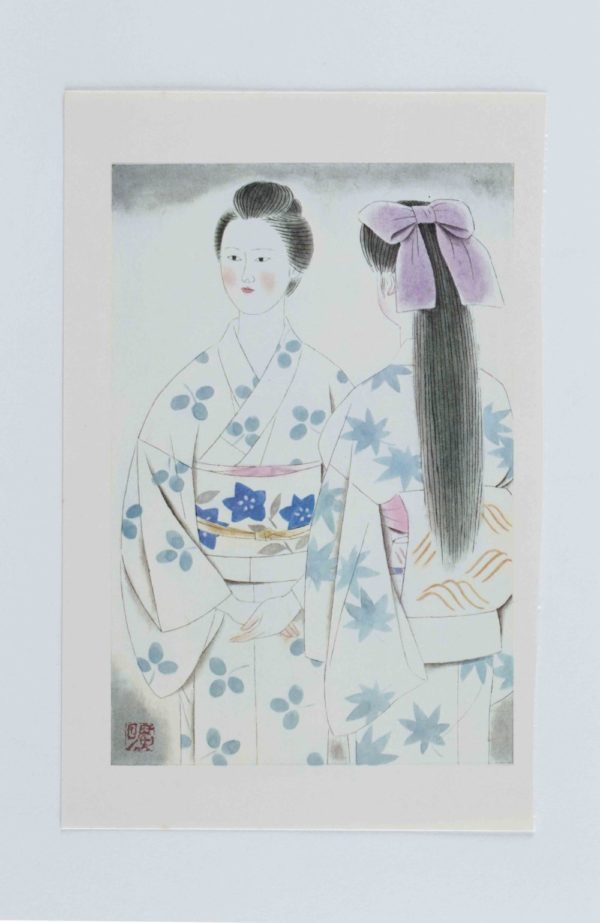

At the Yayoi Museum, Tokyo (a sanctuary for those interested in Japanese girls’ culture) the current exhibition Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May, and sheds light on the desires and love of women who did not submit to the strict gender social norms of the Taishō era (1912-26). Way before the Japanese Woman’s Liberation movement of the 1970’s and 80’s and the many forms of expression that sprung out of it (such as shojo and shonenai manga), these women artists were following their own instincts on what was genuine and true, and created beautiful writings and other forms of art which defied authority and preconceived ideas about gender roles. Some of these women are featured through displays of rare photographs, drawings, writings, and other documentation.

Observing the current gender roles of Japanese society, there is definitely an imbalance in between sociocultural expectations and what the actual people can provide.

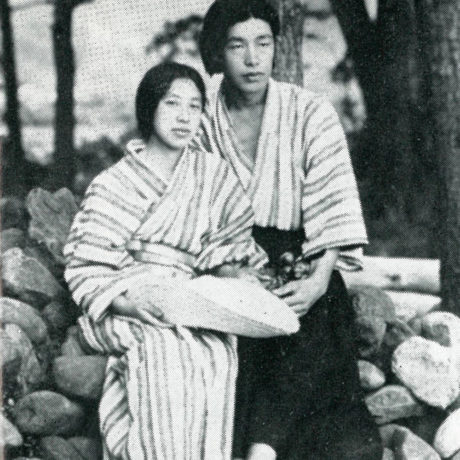

Contrary to her reputation as the pioneer of feminist activists, Raichō Hiratsuka is known to have had a very introverted and shy personality, which even caused her to become voiceless at times. Both her elopement at the age of 21, and her non-marital relationship with a younger man Hiroshi Okumura (who became her life-long partner) socially labeled her as a scandalous woman, and she received severe criticism, but by observing the exhibit, her actions seem to have only sprung from her genuine sincerity towards life, transcending any kind of cheap romantic melodrama. Describing the unique traits of Okumura in her writings, she called him “an odd being, almost like a gigantic baby” “he was 50% child, 30% woman, and 20% man.” Raichō founded the feminist magazine, Seitō (Blue Stocking), which bombarded the Meiji/Taisho patriarchal society with many innovative writings about women and their rights, and was an energetic writer and feminist activist until her death at 85. She is the famous one now, but one should never forget Okumura, a rare gem for someone like Raichō in that time and age: a man who was able to feel comfortable in his progressive gender role, understanding and supporting her over the years.

Toshiko Tamura, a popular writer most active in between 1910 and 1916, first received attention when her husband entered her work in a competition for prize novels for one of the major newspapers of the times, and won. She was bisexual and engaged in many affairs with women writers and artists (she wrote for Raicho’s magazine, Seitō, and got involved in an affair with fellow contributor, Chieko Naganuma, wife to be of renowned poet, Kotarō Takamura), and her sensual and decadent novels about independent women who lived passionately, defying gender roles, created a new chapter to women’s desires. Also, known as an actress, she was wild and elusive, always longing for the unseen land, and spent 18 years living in Vancouver, Canada, and died in China where she established a Chinese feminist magazine.

Akiko Yosano, poet and social reformer, was an energetic fireball that seemed to hold a yin and yang of both the male and female gender. She is known for her relationship with author and poet, Tekkan Yosano which started when he was still married to another woman, and is famous for her volume of tanka poems, Midaregami which came out in 1901, when she was 23 years old. The collection of love poems expressed individualism and passion in a way that no women had done until then and set the stage for women to open up not only about their sexuality and bodies, but to be confident about themselves being navigators to their own lives. Akiko was an extremely talented and prolific writer, and as she gave birth to and took care of twelve of Tekkan’s children, she also became the main breadwinner with her writings, as Tekkan fell into a slump as a writer. But throughout her life, Akiko loved him passionately, supporting his career, and they managed to form a lasting partnership, establishing the first co-ed university in Japan together.

It was a blazing hot August day, that I visited this exhibit, and although I really wanted to take care of some work errands, I rushed to my partner’s home as it was the first day of obon festival (Japanese Buddhist custom to honor the spirits of one’s ancestors). Quite contrary to my own upbringing, within many traditional families here, obon is still treated as one of the most important events of the year. And it is often the women of the family that handle almost all of the preparation, from cleaning the house, preparing the altar, to cooking, and so on. There was an unspoken rule that prevailed, despite the fact that we were living in the 21st Century. It was just the way things were. So rather than protest and waste energy, women choose to follow and carry out the ceremony in a duly manner. Get it over with. And so the deep-rooted cycle to succumb.

I wonder if Raichō, Toshiko, or Akiko would have done the preparations for obon, too? I’m sure they all did. But in their writings, they would never “give in,” and it is through the accumulations of these individual resistances, that women in Japan have gained the rights they have now (well, at least we’re not ranked 144th….). The three women’s determinations were supported by their partners with flexible, gender fluid minds who were able to waltz along with such strong forces beyond the scope of the female sex. Virginia Woolf and Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote that great minds are androgynous and all people hold both female and male sex inside, and by maintaining their perfect balance, one is able to gain harmony. Today, in Japanese sociocultural system and beyond, there is a strong necessity to subvert and negate the construction of a singular strong masculine or feminine ego. Instead, we should all start learning the art of the “in-between.”