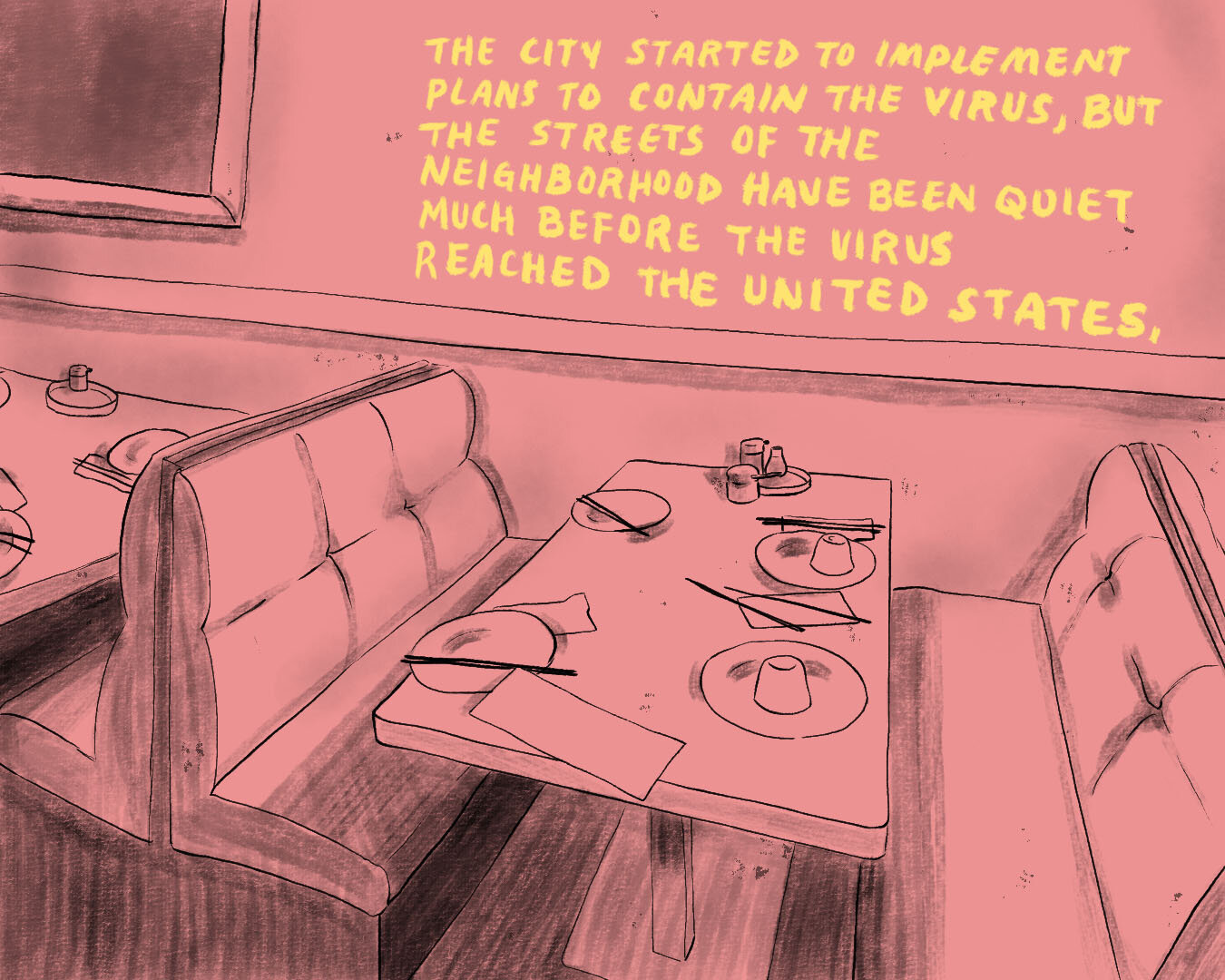

On an April afternoon in Seattle, Washington, business owners in the Chinatown–International District (CID) noticed new additions to their storefronts: stickers with the phrases “Better red than dead” and “America First”, and the name of white supremacist group Patriot Front. This is one of many instances of anti-Asian violence and xenophobia roaring through the United States and countries worldwide, in racist response to the Covid-19 crisis. When it came so close to their home in the CID, interdisciplinary artist Monyee Chau, who uses the pronouns they/them, launched a visual response.

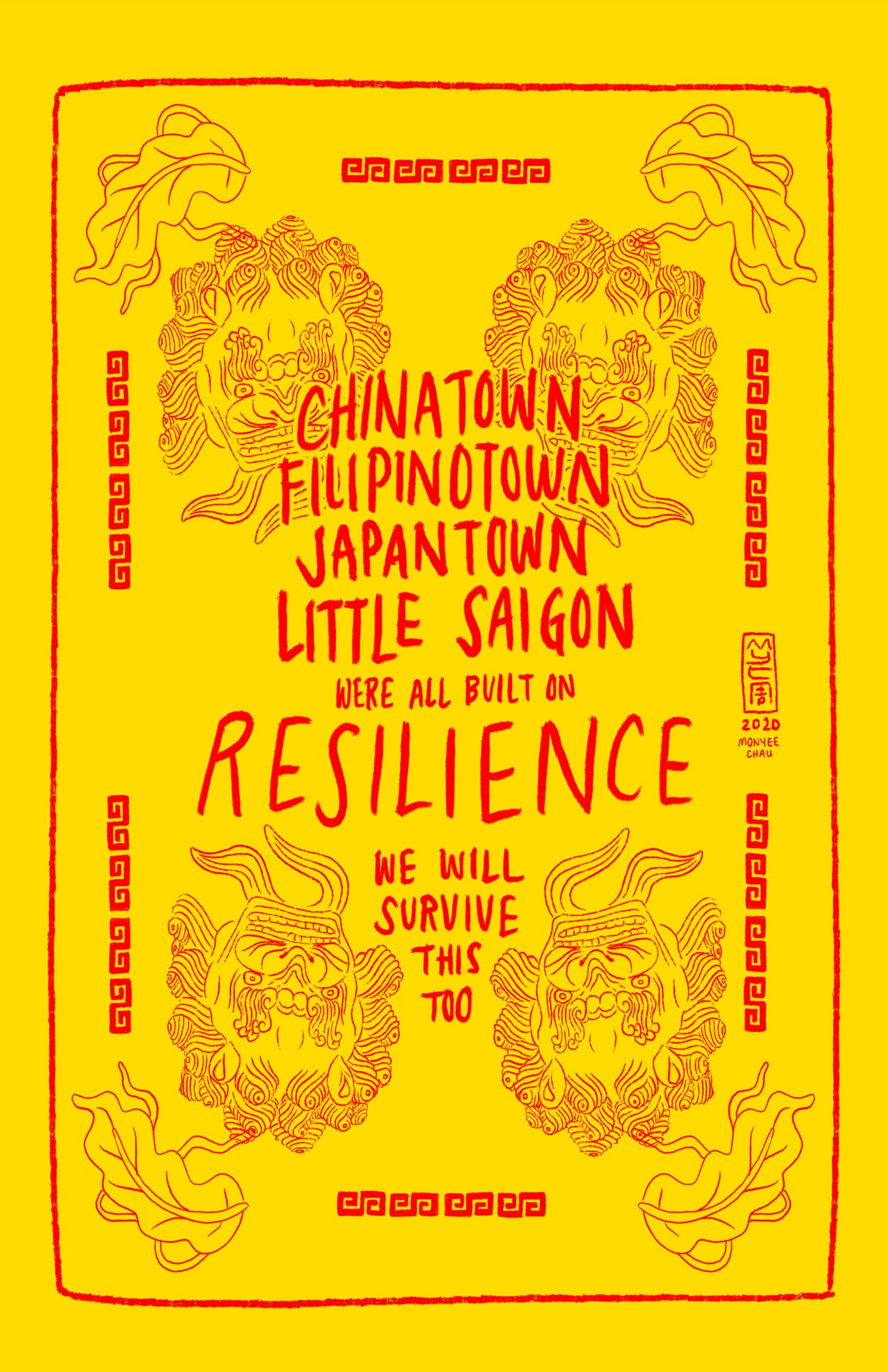

Chau’s red and gold “resiliency poster” reminds the Seattle community—Chinatown, Filipinotown, Japantown and Little Saigon—that they were built on exclusion and “yellow peril”, as Chinatowns have been safe havens from discrimination since the mid-nineteenth century. “We will survive this too”, Chau writes defiantly on the poster. On social media, the response was resounding. One individual paid for 750 posters to be printed and pasted on walls and telephone poles in the CID. The poster is available for anyone to download because, as Chau explained to me over the phone in July, propaganda is a crucial tool in any uprising.

“Chinatowns have a really unique perspective in the way that they’re experiencing Covid. We’re also so vulnerable to gentrification”

“Chinatowns have a really unique perspective in the way that they’re experiencing Covid. We’re also so vulnerable to gentrification during this time as private developers are trying to use this global pandemic to their advantage,” Chau, who is 24 years old, says. “And this place means everything to me.”

Chau’s family, immigrants of Taiwan and China, owned a seafood restaurant in the CID’s central nexus. Chau grew up sitting on the counter, watching over tanks of squirming lobsters and their grandmother peeling garlic cloves. A drugstore chain now sits in that lot, but Uwajimaya, the popular Asian supermarket, remains one block down. Around the corner is Chau’s apartment, and the former Louisa Hotel, where Jimi Hendrix’s mother was a Prohibition-era bartender and racial integration was encouraged.

The Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience is up the hill, named for the first Asian American elected into state government, who passed instrumental anti-discrimination housing laws; last year, Chau made a resiliency comic as a fundraiser for them. As Seattle goes the way of San Francisco—extreme gentrification ushered in by the tech boom—this neighbourhood is a final vestige of visible (minority) history.

It was the restaurant, which closed in 2004, that inspired Chau to address identity in their art practice for the first time. Chau’s aesthetic style, from their tattoos to their labour-intensive embroidery, stem from the same familial source. “The gimmicky burden of being a Chinese restaurant, as the introduction to the ethnic ‘other’ for a lot of Americans—there’s so much weight to it. So I think that imagery is beautiful,” Chau says. “We [Asian Americans] live in such a liminal space. I went to Chinese school for, like, six years but I was embarrassingly bad at it. So the Chinese is often really broken in my art because it’s from my dad or from Google Translate. And I’m not going to be ashamed of that anymore because, as an Asian American, that’s very literally my experience.”

It didn’t matter that the material artefacts were hard to find; the filter of half-remembered stories and reconstructed images from stock photos became the work itself. “Asian families tend to not talk about stuff as a means of dealing with their trauma and not wanting to share how hard things were,” Chau says. “I have to pry it out of them but in a way that’s safe, an environment where they feel like they can share.”

In the conceptual piece A Day’s Work of Labor and Love (2017), Chau constructed pale pink dumplings out of hot glass, because glass is strong and can be permanent, but fragile if you don’t take proper care. The same can be said of heritage.

“Chinese blood runs through my veins first,” Chau says, on why they understood themselves as Chinese-born American rather than American-born Chinese, an identity that is “a whole new experience” instead of “an in-between.” “I learned a native saying from the [two-spirit artist and educator] Storme Webber: ‘When you heal yourself, you heal seven generations forward and seven generations back.’ That’s about collectivism, which I think people in America have really lost… There’s a lot of broken things inside of me that this work definitely helps heal. I’ll be able to share that process with my future generations and I hope that my past generations are proud of me for learning to love myself, which is a revolutionary act for queer folks to do.”

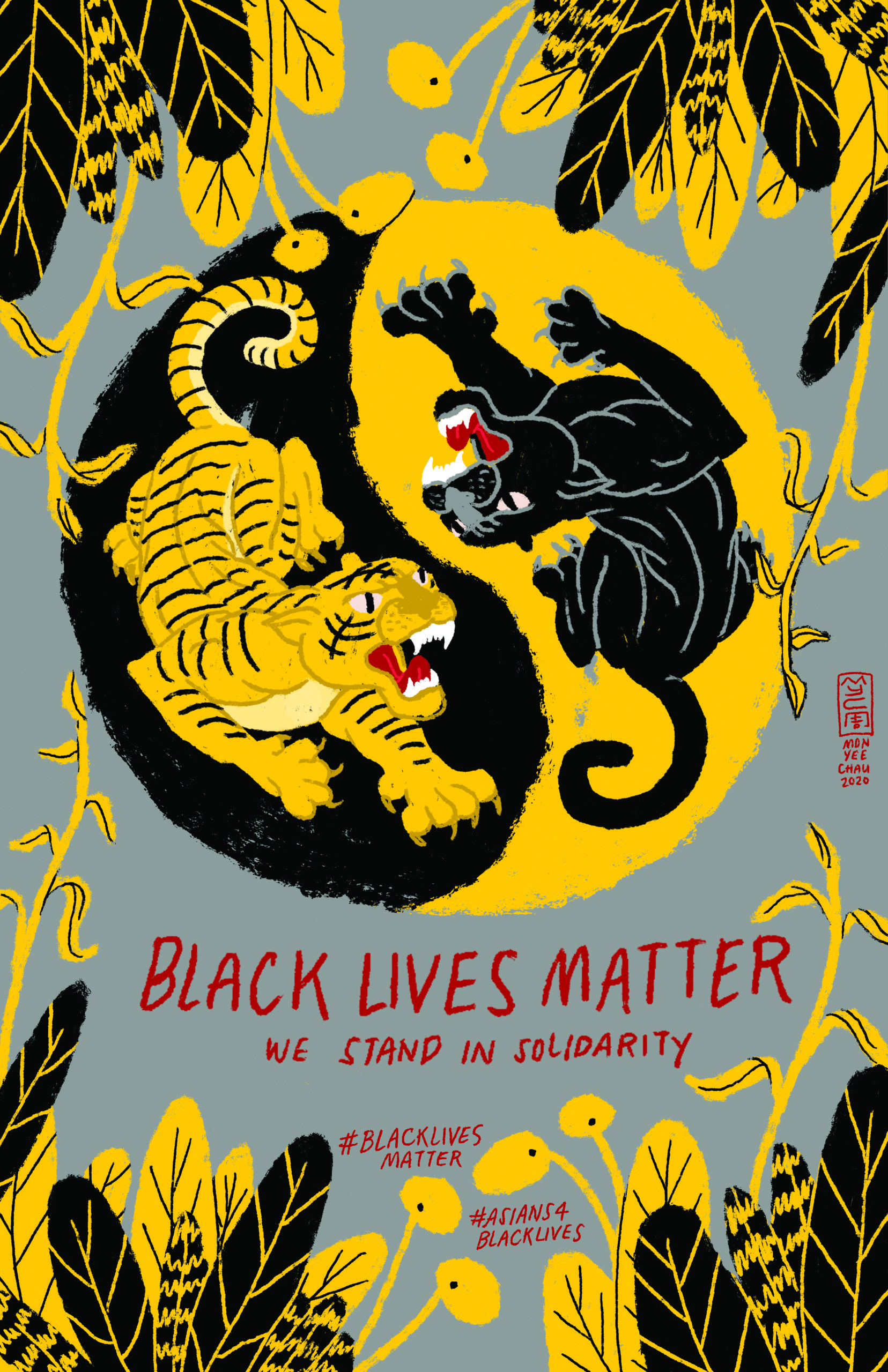

The revolution of this moment is Black Lives Matter, the largest protest movement that many have ever witnessed. Directly north of the CID is Capitol Hill, which made headlines for the establishment of an occupied protest or police-free “autonomous zone” after a week of stand-offs and tear gas. In the days after George Floyd’s murder on 25 May, Chau channeled their grief into a poster inspired by Asian supporters of the Civil Rights movement, with the slogan “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power.” The phrase appeared on placards at protests during the 1960s, when Asian Americans tried to reclaim the racist “yellow” term and their histories. Chau posted the design on Instagram, where it garnered more than 50,000 likes; they also made the artwork available to download so others could use it on posters and signs.

“I made that piece out of wanting to be of support and to encourage folks to feel empowered to be in the streets, to show our solidarity,” Chau says. “I believe Black liberation is intertwined with liberation of all colonized peoples. But there was a lot of controversy. Some folks reached out to me who thought that I was centring Asian struggle over Black struggle. It was incredibly conflicting because even though I’m an internationalist, I understand that [the slogan] can perpetuate harm and can give Asians an excuse to not be in the streets and to just post this image on Instagram. But that’s sort of what happens with art any time, right?”

Chau themselves went from 4,000 followers on the app to more than 20,000. They have since altered the text on the poster, and the design is now being sold on a shirt, with the proceeds going to Equal Justice Initiative. Several of Chau’s lifelong Asian Pacific Islander role models, from restaurateur David Chang to actor Ken Jeong, reposted the image. It was displayed in windows on London’s Oxford Street, as selected by W1 Curates.

“I’ve learned how to be quick and funny but educational, and how that can translate to spreading political information for the masses”

“With the reach of social media, I get to watch other Asian artists do such amazing work,” Chau says. “Our schools don’t teach us anything like that. [I’ve learned] how to be quick and funny but educational, and how that can translate to spreading political information for the masses.”

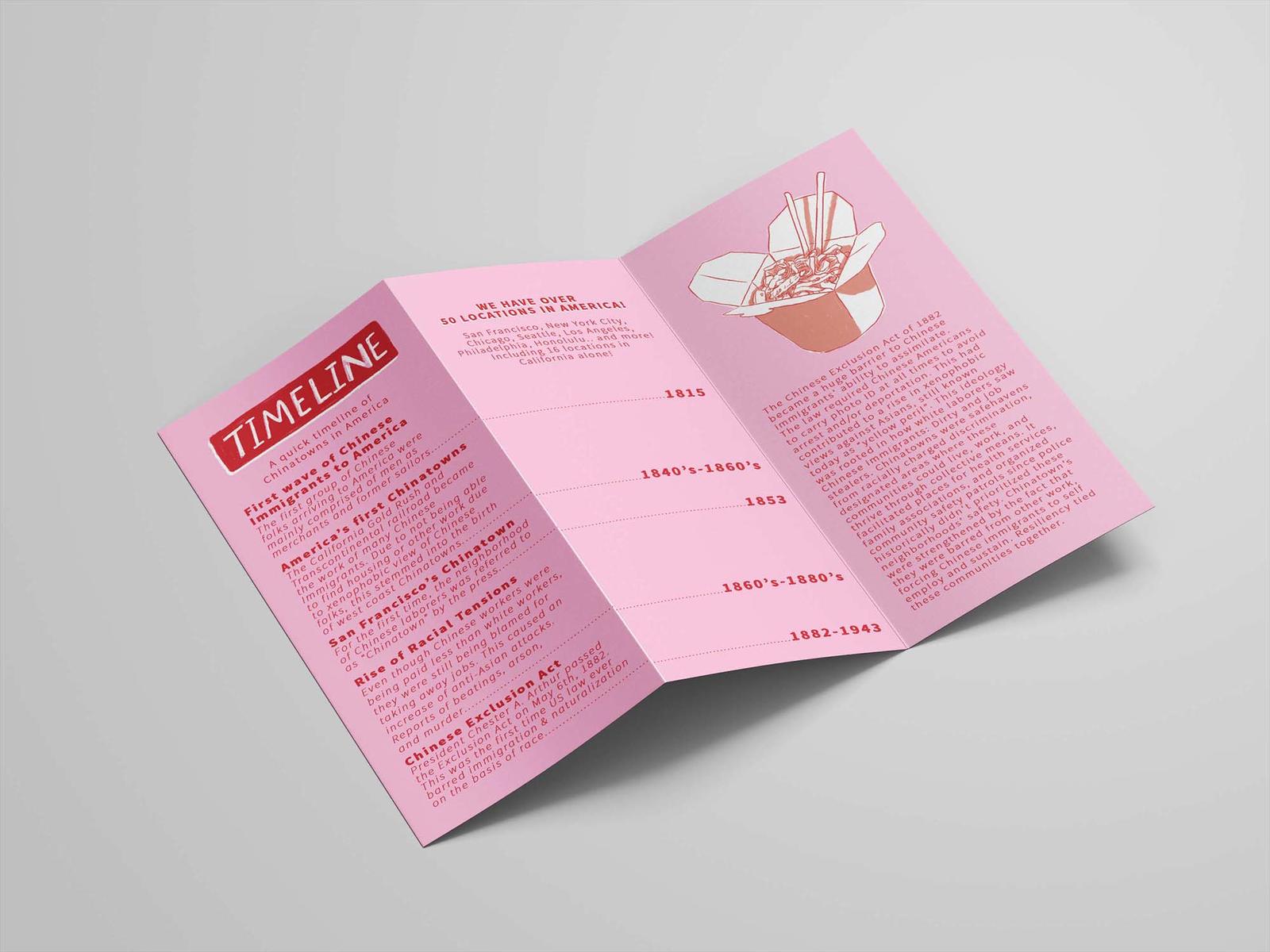

Chau used the quirky format of a take-out menu to debut another resiliency artwork, a history of Chinatowns across America and the racism that built them. This too is available to freely read, download and print. Accessibility, they explain, is the logical next step in a decolonial art practice. Last year, they made a colouring book zine about the Chinese zodiac, with the story of the great race that was historically told on Chinese restaurant placemats. Their next major project will see them move to Los Angeles to explore the anti-gentrification work in a Chinatown that is unfamiliar to them.

“One of my dream art projects is to travel to America’s Chinatowns and make art informed by all of it,” Chau says. “My work doesn’t encompass all Asian American experiences but it does encompass mine.”