Melanie Bonajo

Intimacy and female pleasure have been at the centre of some of Melanie Bonajo’s most powerful works, and they often include the voices of those who have direct experience of sex work and activism. In spring, they will represent the Netherlands at the Venice Biennale.

Having long explored the idea of eco-feminism, their practice is becoming ever more pressing as the climate crisis heightens. They have a unique way of bringing environmental issues together with body politics and technology, and their aesthetic is instantly catchy: they combine video with installation, creating immersive environments flooded with bright hues and tactile materials. One to watch in Venice. (Emily Steer)

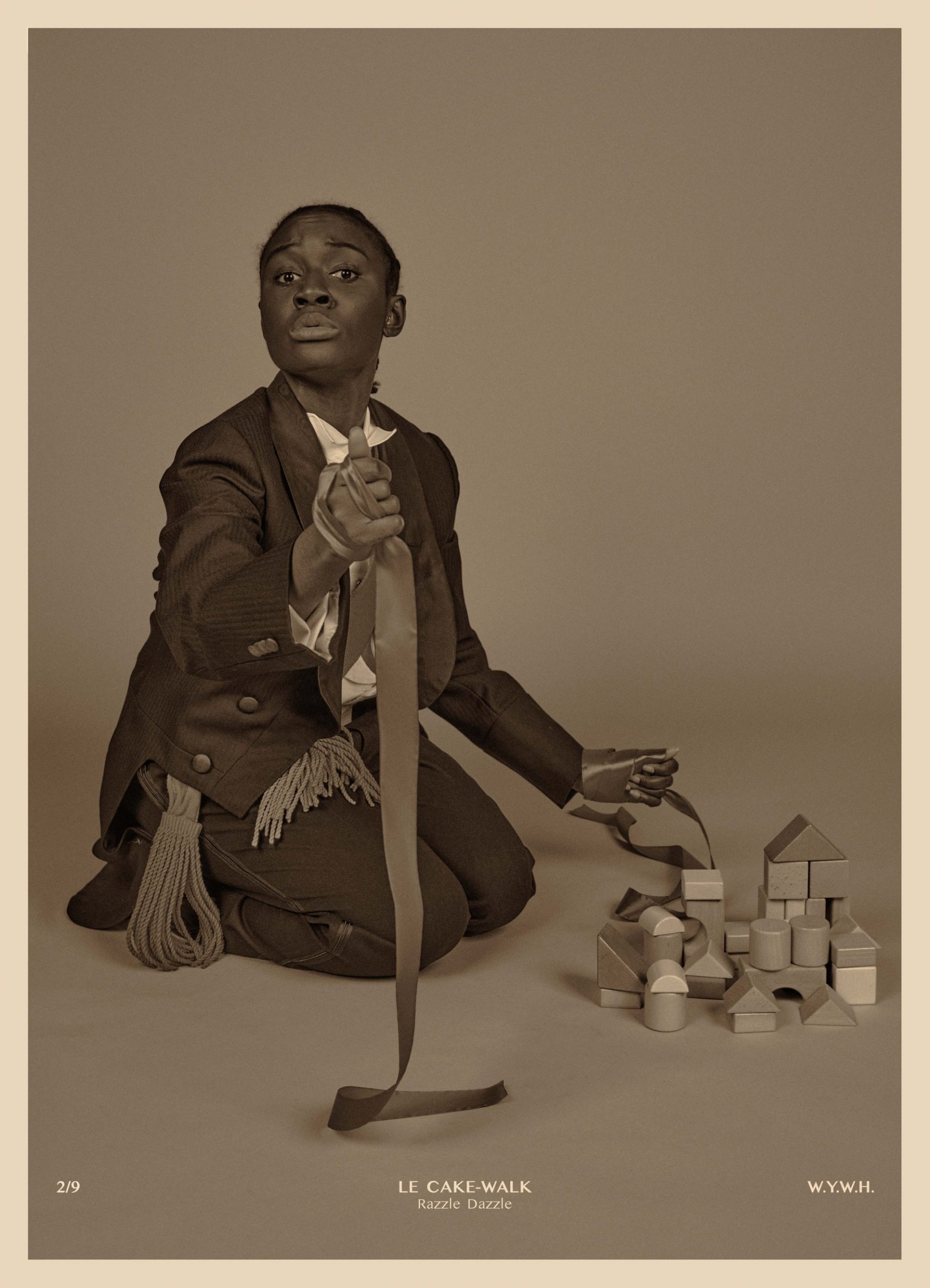

Heather Agyepong

With a practice that spans performance, acting and archiving, the London-based visual artist’s Wish You Were Here series led to widespread acclaim in 2020 (the series is available to view online as part of Foam Talent 2021 until the end of January). The work celebrates the Black community while “not wanting to be burdened by representation and identity politics,” Agyepong explains.

She instead turns to a heavily choreographed reconstruction of the life of early 20th century vaudeville performer and actor Aida Overton Walker, allowing her strength in post-Reconstruction New York City to answer the question of “What would a radical image of reclamation looks like?” Agyepong will this year work on her Jerwood/Photoworks Award project in anticipation of an autumn showcase, while also continuing projects as part of The Photographers’ Gallery’s New Talent 2021 scheme. (Ravi Ghosh)

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

In a year when lockdowns around the world forced many galleries and museums to close their doors and go virtual, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s work came into its own. The British artist uses animation, sound, performance and video games to create works that live on the internet, and which she often refers to as ‘games’. These digital experiences are guided by richly evocative speculative fictions, in which questions of identity, landscape and history frequently arise, and in which the audience is invited to actively participate.

She sets out to communicate the experiences of being a Black Trans person. The accumulation of this output is stored as a ‘Trans archive’ as Brathwaite-Shirley terms it, where the “history of trans people both living and past” is recorded for posterity. Following a standout solo show of 2021 at Focal Point Gallery, the artist will present a new interactive digital commission at Spike Island in Bristol in March 2022, in which the actions and identities of her audience will influence the evolution and structure of the game. (Louise Benson)

Dominic Chambers

Fans of Jennifer Packer and Arcmanoro Niles will gravitate towards Dominic Chambers, the Saint Louis-born painter whose figures stand tall, read or rest in his colour-drenched scenes. His solo show Progress of the Soul concluded just before the end of last year at Luce Gallery, Turin, where Chambers created large oil and drawings on paper exploring the intersection of African-American identity and magical realism, channelling the isolation felt over the pandemic months.

Last year, he featured in shows at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Florida’s Norton Museum of Art. In 2022, after representing the gallery at Art Basel Miami and Frieze New York last year, Chambers will mount a solo show at Lehmann Maupin in February. Even in his darker, more muted works, his figures lose none of their monumentality. (Ravi Ghosh)

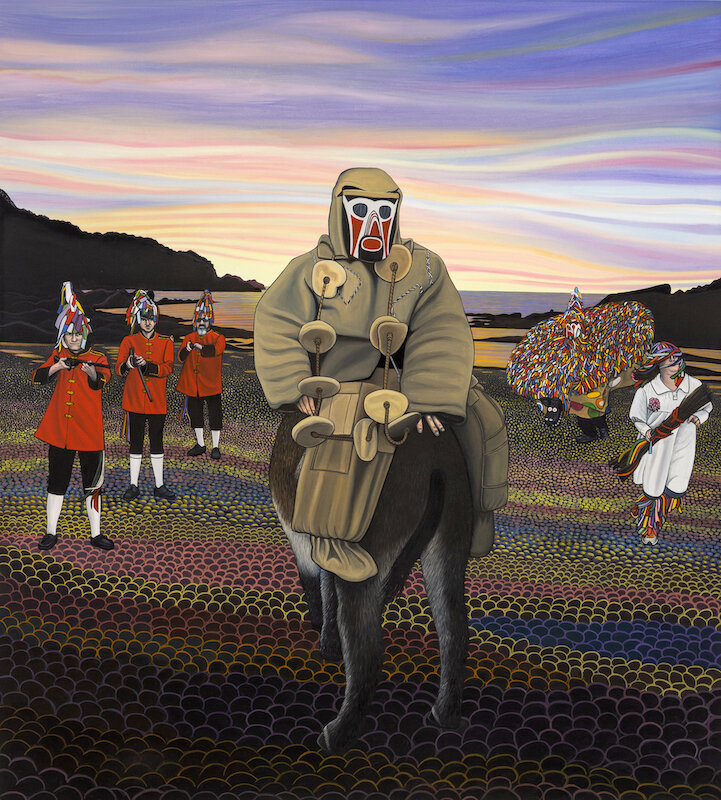

Ben Edge

An exhibition in a crypt and a night on a galleon are just a few of the more left-field ways that Ben Edge has spread his knowledge and love of British folk art during 2021. The artist has travelled across the country, seeking out monuments, ceremonies, rituals and celebrations that often go overlooked or under-appreciated, collating meticulous research.

While he previously focused solely on paintings to reveal his findings, Edge has also collated an enormous archive of photographs, film and objects, all of which informed the enormously popular Ritual Britain exhibition (in collaboration with the Museum of British Folklore) last summer. Looking ahead, another event at The Golden Hinde (a full scale reconstruction of the first English ship to sail around the world, situated near London Bridge) is on the cards for 2022, as well as the full-length film Frontline Folklore, and another that focuses on ancient stone circles. (Holly Black)

Rachel Jones

British artist Rachel Jones had an incredibly strong 2021. She was one of the stand-out artists in Hayward Gallery’s hugely popular painting show Mixing It Up and in December she opened SMIIILLLLEEEE at Ropac in London to critical acclaim. Her exhibition at Ropac continues until early February this year, followed swiftly by a solo show at Chisenhale.

Her punchy, colourful abstract works are a breath of fresh air in an art world saturated with figurative work, and her inspirations are unique: each painting depicts a row of teeth (not that you’d know it on first glance). Visceral, emotional and entirely original, her star is only going to rise this year. (Emily Steer)

Ifeyinwa Joy Chiamonwu

The Nigerian artist uses charcoal, sepia, pastels, paints and coffee to create vibrant portraits of friends as family recast as mythical figures from the narratives of her Igbo heritage. Often photographic in their detail and sharpness, Chiamonwu’s works are acts of preservation and documentation as well as expression. “My art tells a story of typical Igbo culture before Westernisation and globalisation,” she says.

That makes presentation in Western galleries especially delicate and intriguing, a task the artist will undertake with New York City’s Jack Shainman Gallery for a January 2022 show. One work depicts Anyanwu, the Igbo deity responsible for knowledge and spiritual awakening. Chiamonwu allows the stories around these characters to influence her depictions: “I came up with the idea to present the artwork as an archaeological antique painting, which was lost a long time ago but finally found and preserved for future generations,” she writes. (Ravi Ghosh)