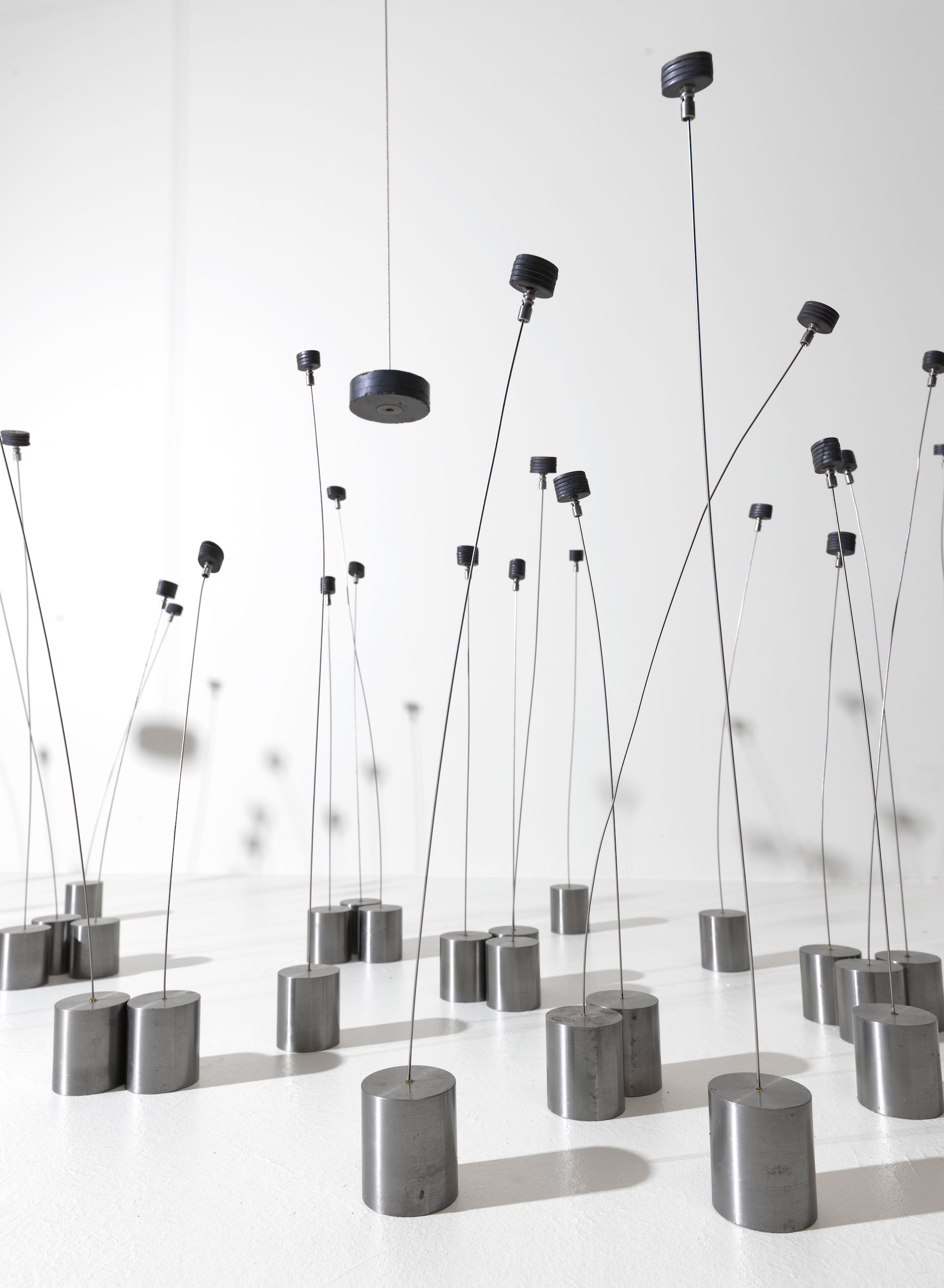

The natural world has been an inspiration for artists for centuries, through painting, sculptures, and now, in the context of video and work in virtual reality. In the case of Greek artist Takis, whose retrospective at the Tate Modern has just opened, his training as a figurative sculptor combined with his later movement into a kind of quasi-scientific practice. One of the most original artistic voices in Europe from the 1960s, he explored the creative possibilities of electromagnetism. Visitors to the show are first drawn to a swaying collection of wires, with round magnets connected to them. Swinging magnetic pendulums make those wiry sculptures sway, compelled by a seemingly imperceptible force. These works were at the cutting edge of art and technology at the time.

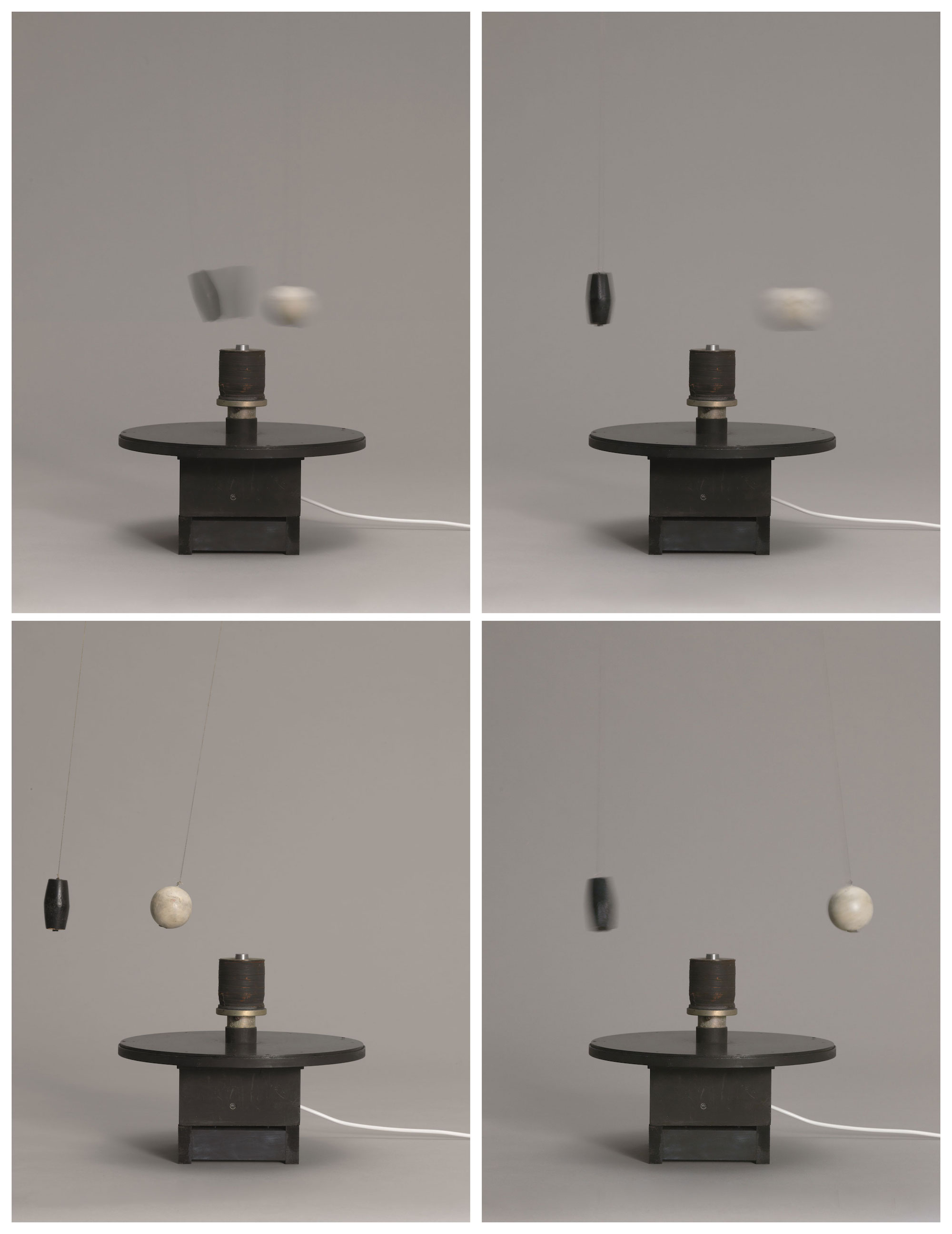

Other works in the exhibition draw on the presence of the invisible forces to create sound and movement, such as a musical sphere which generates random, cosmic sounds, and the magnetic ballet, a series of rotating balls and magnets which seem to move of their own volition. His materials themselves are sparse and immense at once, working with natural invisible forces to imbue them with life, as if working in negative space. His practice contains a kind of reverence for the natural world, and reflects an anxiety about how we come into contact with it.

Increasingly, contemporary artists working in new technology today often look to the natural world as the site of enquiry and extraction, partially to catalogue how the forces of nature and the world may shift as we plunge into deeper crises. In some ways, their predecessors were the works of artists like Joan Jonas, whose mixed media installations dabbled in several mediums and create an emotional connection with the viewer. All raise questions about the way we understand and rationalize what we know about our world, whether that’s in the greenery we fawn over, or radiation we can’t perceive.

“Takis’s practice contains a kind of reverence for the natural world, and reflects an anxiety about how we come into contact with it”

One of Takis’s works on display at the Tate Modern is an immense gong, rung every ten minutes by an assistant, which reverberates across the room. This is a reference to the music of the spheres, a concept Takis was fascinated by—the sounds and harmonies created by celestial bodies as they moved around each other. Audiences may come even closer to comprehending the music of the spheres in an encounter Polish sculptor Alicja Kwade’s Parapivot intervention, a site-specific installation currently exhibited in New York on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s roof.

It consists of nine spheres of varying sizes, made of fascinating marble from around the world, each of which represents one of the planets of our solar system. Kwade’s calling card has always been a playfulness with the laws of physics, such as her previous copper sculptures—here, she balances these spheres precariously on top of steel frames at angles with each other, with some of the spheres even seemingly balanced in mid-air. Their delicate balancing act transforms the expanse of a roof into a reflection on the cosmos.

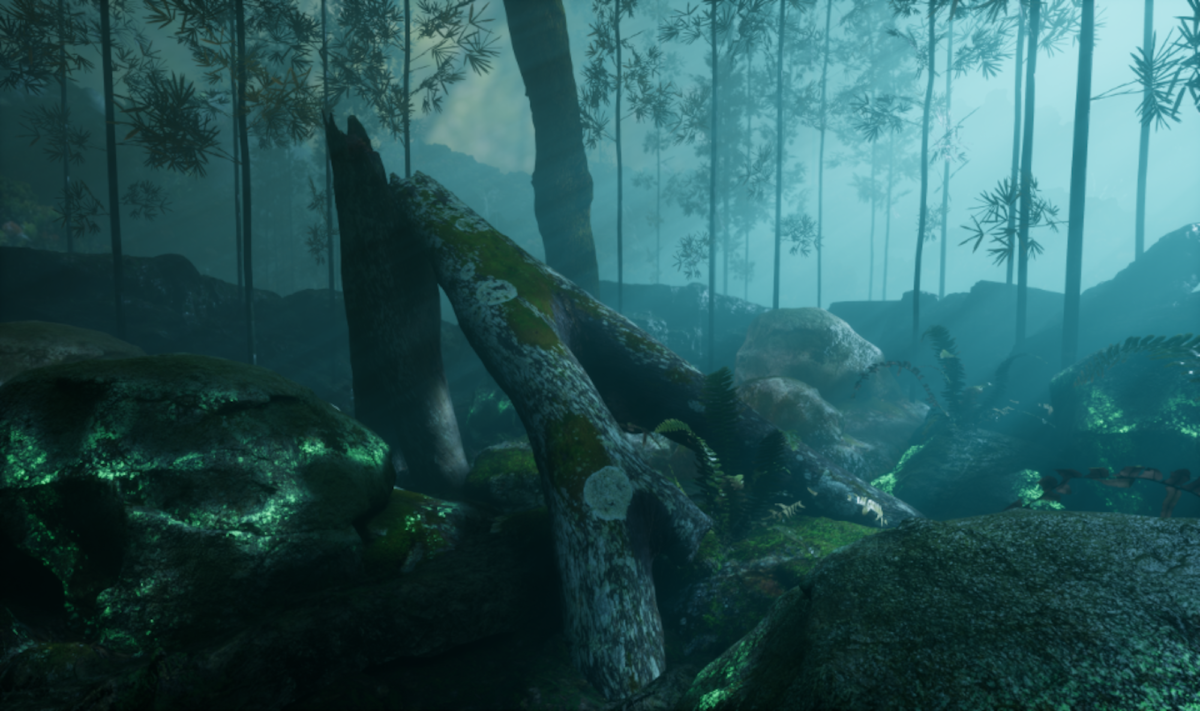

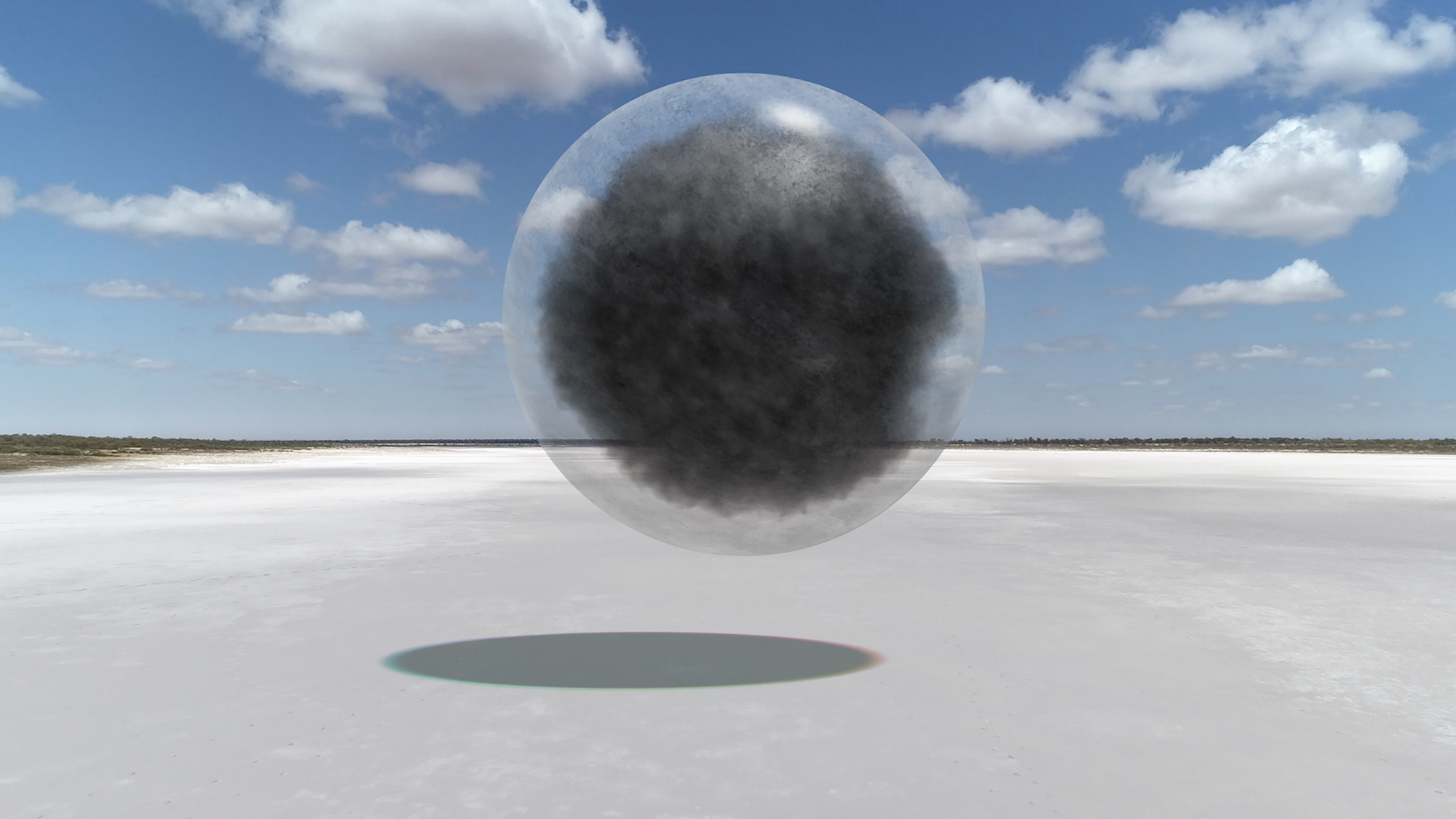

Meanwhile, glowing spheres float across the vast Australian landscape in the work of Laurent Grosso, whose multimedia exhibition OttO was on display at Perrotin in 2018. OttO is concerned, much like Takis’s work, with the imperceptible but very real forces of nature such as radiation, and the site of the installation becomes a space for visitors to come into contact with them too, through the placement of a Steiner machine and measuring devices around the gallery.

The film OttO was shot in the Australian desert, and Grasso worked with indigenous groups and arts organizations, using thermal cameras to reproduce and demonstrate the electromagnetic waves and radiation emitted from these lands. Ordinary visual references—the mossy boulders dotted around the land, or the familiar arid and orange hue of a desert—are made unnerving by the levitating spheres above them.

“As the materials available to artists shift, that overlap between technology and the natural world can also take on new, speculative forms”

Grasso uses digital technology to create the otherworldly spheres and superimpose them into a “true” natural landscape. In OttO, the camera itself—the technology used to document the work—becomes a kind of entity, like a measuring device which can expose new aspects of seemingly familiar landscapes, in some way different from just looking at it with naked eyes. As the materials available to artists shift and change, that overlap between technology and the natural world can also take on new, speculative forms.

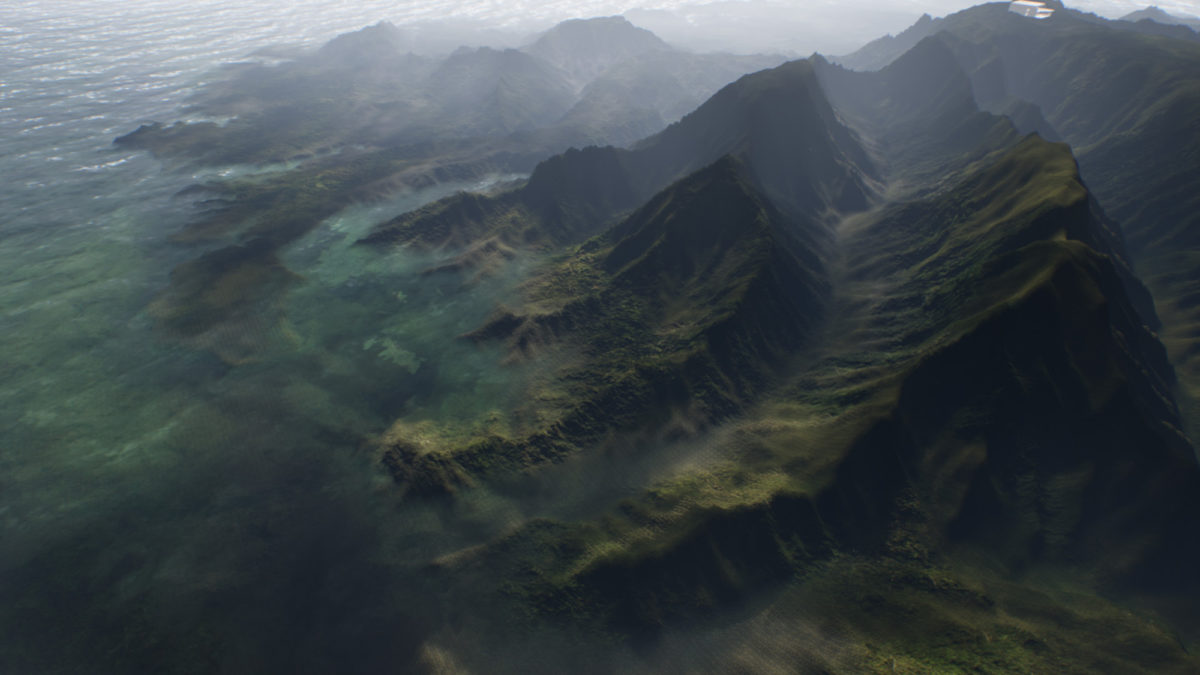

Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s work sits in that same intersection between technology, the environment and imagination, too. One of his most recent works, RE-ANIMATED, is based around the mating call of a bird which became extinct in 1987. Kudsk Steensen interviewed ornithologists and undertook what he terms “digital gardening”, collecting and planting various species of plants and nurturing animals in a virtual land that Steensen designed with algorithms.

The RE-ANIMATED landscape reacts to the stimuli that each individual visitor brings in—even imperceptible details, such as how they breathe and shift the virtual atmosphere. Everything seems familiar enough, but it isn’t quite right. Steensen draws on slight modifications in what we can know from our world—such as the texture of water, the movement of light—to draw attention to the way we understand and alternatively ignore the changes in our ecosystem.

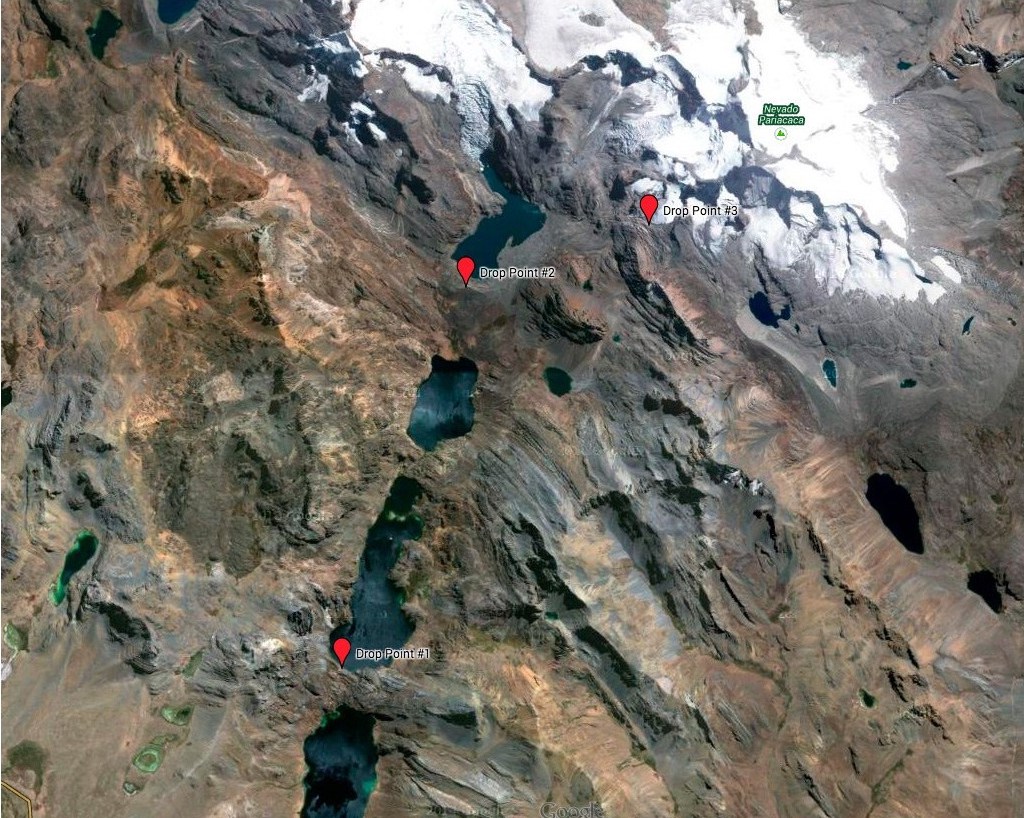

While Steensen documents the natural world as the basis for digital textures in his installations, other parts of the world cannot be so easily documented. Glaciers recede and melt, releasing long-dead organisms or plant matter which provides clues about the ecosystem the glaciers are a part of. In effect, they erase their own history. Digital artist Mark Dorf sought to document a specific glacial range, the Pariacaca in the Peruvian Andes, through photographing them at specific locations and placing these images on separate USB drives. Following this, the USB drivers were cast in concrete and made waterproof, and then placed at the exact location the photographs on them were taken at.

If you want to see the photographs, you must physically visit those coordinates. What those glaciers looked like, at that point in time, is only available in that physical space itself—no version exists in a virtual reality or online. But those USB drives are not being maintained by Dorf; it’s up to visitors if they want to repair or maintain them, or in some way even alter the process that Dorf started. In doing so, the USBs become a part of the very ecosystem that is under threat. While we may pay greater attention to the world that we are laying waste to, we inevitably watch it lose some of the elements which made it so compelling.

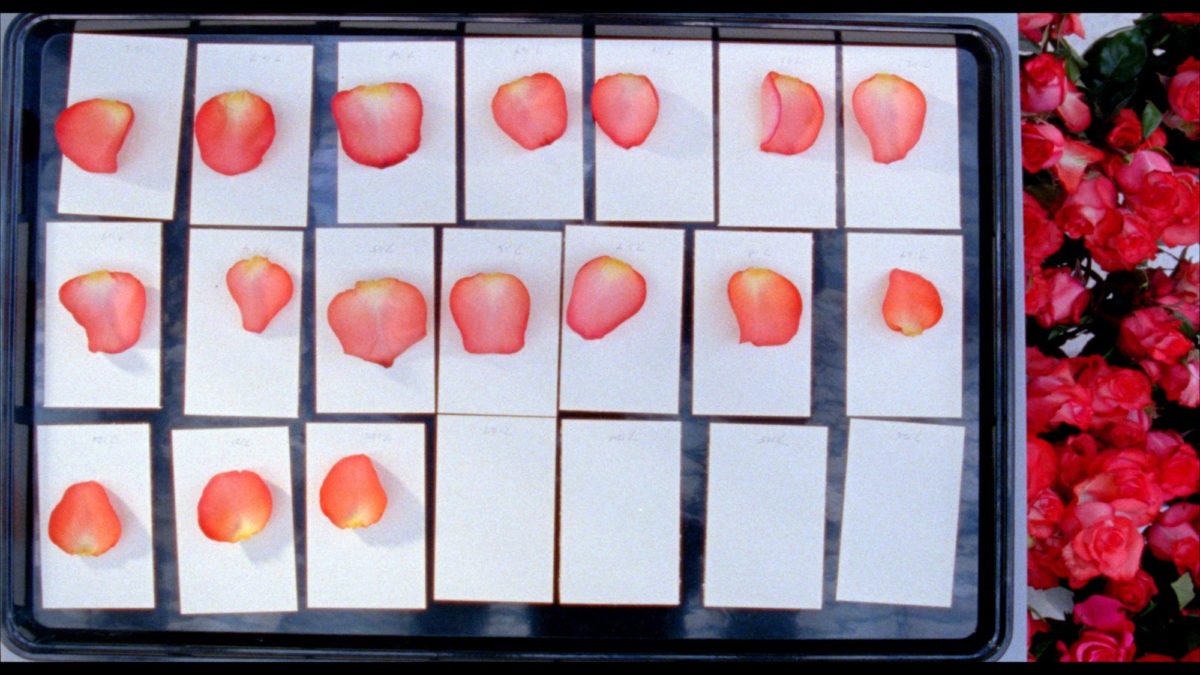

- Cloud of Petals, 2017. Images courtesy of the artist

The subjective nature of cataloging the natural world is a key preoccupation of the work of Sarah Meyohas, whose installation Cloud of Many Petals used technology from the now defunct Bell Labs to catalogue and generate rose petals. Just as technology opens the door to a closer understanding of the world which we already exist in, it proposes new challenges for how we categorize it. A team of sixteen male workers, assembled from temporary work agencies, individually selected 10,000 rose petals which they were drawn to, and painstakingly preserved them in a massive archive.

“Just as technology opens the door to a closer understanding of the world, it proposes new challenges for how we categorize it”

Those images then became the dataset to train an algorithm; it was taught to generate new, simulated rose petals, as part of a VR installation, where human involvement dictates how they move and what they do. But they’re virtual, and they can never possess the sensory qualities of the real thing. Hito Steyerl’s GAN generated flora at the Serpentine uses the same sense of imperceptible distance between the real and derivative versions of a phenomenon to demonstrate how much more of our reality is fabricated, and what role new technologies can play in that.

These pieces, installations, ideas operate across multiple fields. They’re unnerving even if they’re not classically beautiful, and you recognize scenes in them even if you don’t expect to. In the 1970s, the French surrealist theorist Roger Caillois wrote about diagonal sciences, arguing that the way in which we split knowledge up into arbitrary, tiny channels of meaning leads us to miss out on important, if random, connections.

Takis re-purposed what he saw as technologies of war, such as gauges, radar, antennae, into creations which were far more liberating. He wanted to create work which was at once an investigation and escape into the everyday. New works across video and virtual reality exemplify these ideas too—as we know more about the world, we are supposed to feel closer to it. But in times of crisis, we often turn to anything outside ourselves for meaning, and these works cut to the core of what it means to be curious about the universe we live in.