What does it mean to take a photograph? For many, it is a means of recording a moment in time. It’s a way to remember, from family albums to the pictures stored on the camera roll of our phone.

However, just as it can be a form of truth-telling and documentation, it can also be an act of fiction. When the camera is turned upon the photographer in a gesture of self-portraiture, photography can become a means of questioning and performing identity as well as notions of the self.

In recent years, a growing number of photographers have used the camera not just as a passive tool for documentation but as an active intervention into their own life. These artists make use of photography as a key component within a practice that could be called performance art. For them, self-portraiture is key to this blurring of boundaries.

For Michal Iwanowski, photography is intimately connected with performance. In Go Home Polish (2018), he made the decision to travel across eight countries by foot (from his house in Cardiff to his old home in Poland) following an encounter with a piece of racist graffiti. He took the abusers at their word, and set off on a journey with his camera that he would document in a series of existential self-portraits along the way.

“Michal Iwanowski set off on a journey with his camera that he would document in a series of existential self-portraits along the way”

Far from straightforward documentation of the sights he encountered along the way, they show Iwanowski playing up to the camera. In these shots he becomes “the Polish construction worker, the plumber, the baker”. In doing so, he mocked the hateful words he’d seen, “deliberately making fun of the graffiti, and effectively stripping it of its power”. For Iwanowski, it was a way to fight back.

Photographer Haley Morris-Cafiero took a similar approach with Wait Watchers (2010-15), in which she set up a camera in a public area and photographed the scene as she performed mundane tasks while strangers passed by her. She eats an ice cream at a traffic light, and exercises on a busy street. She then examined the images to see if any of the passersby had a critical or questioning element in their face or body language. “Wait Watchers examines the body that is considered ‘grotesque’ by our beauty standards, transgressing a space where it is not wanted: the public space,” she explains.

“Haley Morris-Cafiero set up a camera in a public area and photographed the scene as she performed mundane tasks while strangers passed by her”

As she puts it, “The project is a performative form of street photography.” For Morris-Cafiero the camera helped capture interventions into social conventions, and the way those conventions are almost imperceptibly policed. But it also did something else, allowing her to insert herself into the scene and assert her right to be there.

Morris-Cafiero’s series bears similarities to performance projects such as Pope L’s series of ‘Crawls’ in New York in the 1970s, which saw him literally crawl on the street, poking fun at and prodding a culture consumed with success yet riven with social, racial, and economic conflict. More recently in White Shoes (2021)

, Nona Faustine photographed herself in New York locations associated with slavery, simultaneously delving into a hidden history and reclaiming those spaces.

Place is central to Iwanowski’s Go Home Polish. As a gay man who was born in Poland, a country now creating entire “LGBTQ-free” zones, he found himself an outsider. In the UK, rising knee-jerk nationalism means that he is still sometimes perceived as an immigrant, despite holding a British passport. Through this work he was actively seeking to claim the land via his presence in each photograph. “Not to own it, but to democratise it,” he explains.

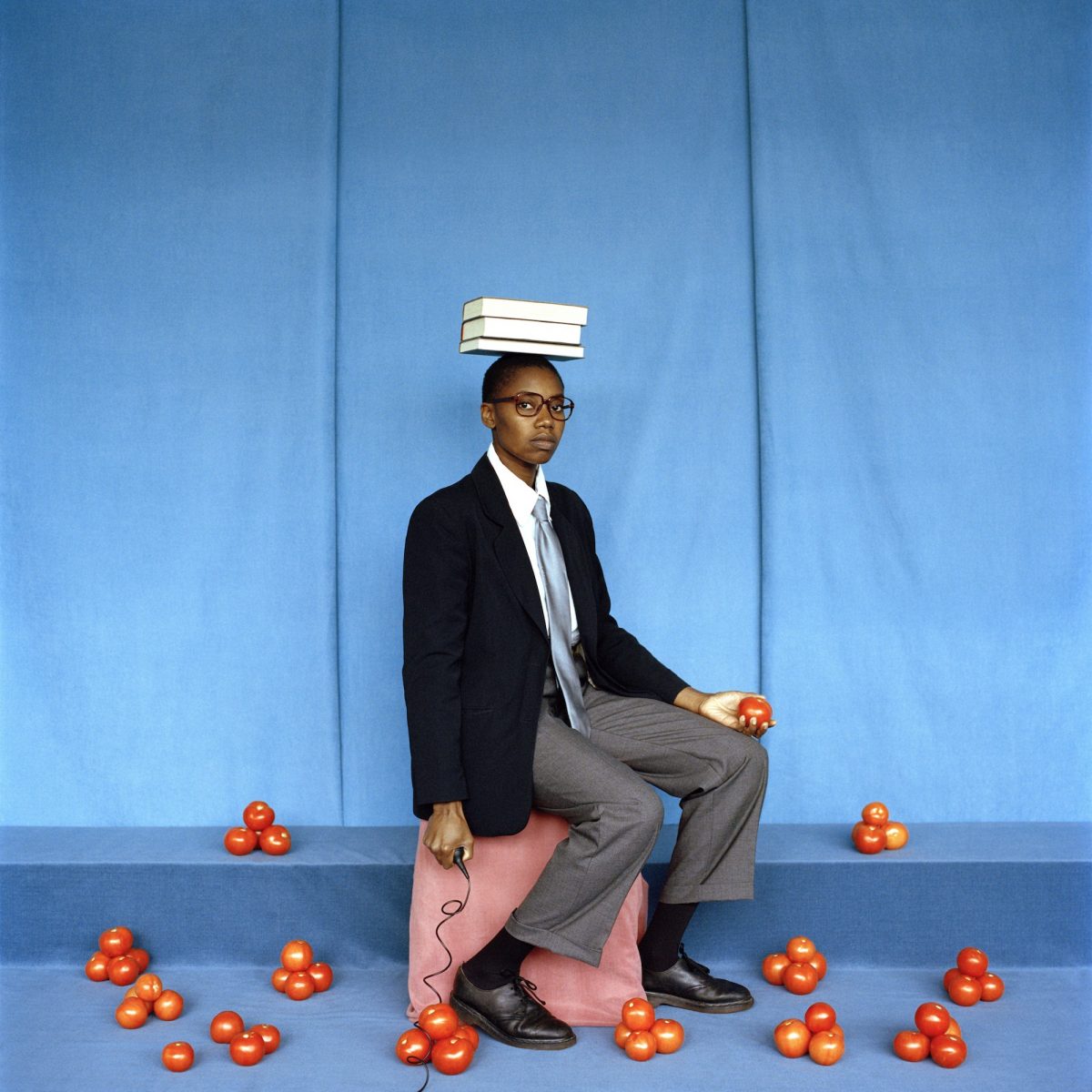

- Left: Silvia Rossi, Self Portrait as my Mother, 2019

- Right: Silvia Rossi, Self Portrait as my Father, 2019

The push-pull between the public and private, personal and shared runs through photographer Silvia Rosi’s images. Her series Encounter (2019, made for the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards), drew upon her own family history, in particular a photograph showing her mother when she worked as a market trader in Lome, Togo.

Inspired by the tradition of West African studio portraits, Rosi created a fictional representation of her family’s migration from Togo to Italy, using backdrops and props. Many of these images pick out the act of head carrying, a skill traditionally passed on from mother to daughter but in Rosi’s case lost through migration and her position as a European. Rosi’s work shows how even the way we move our own bodies is partly shaped by society.

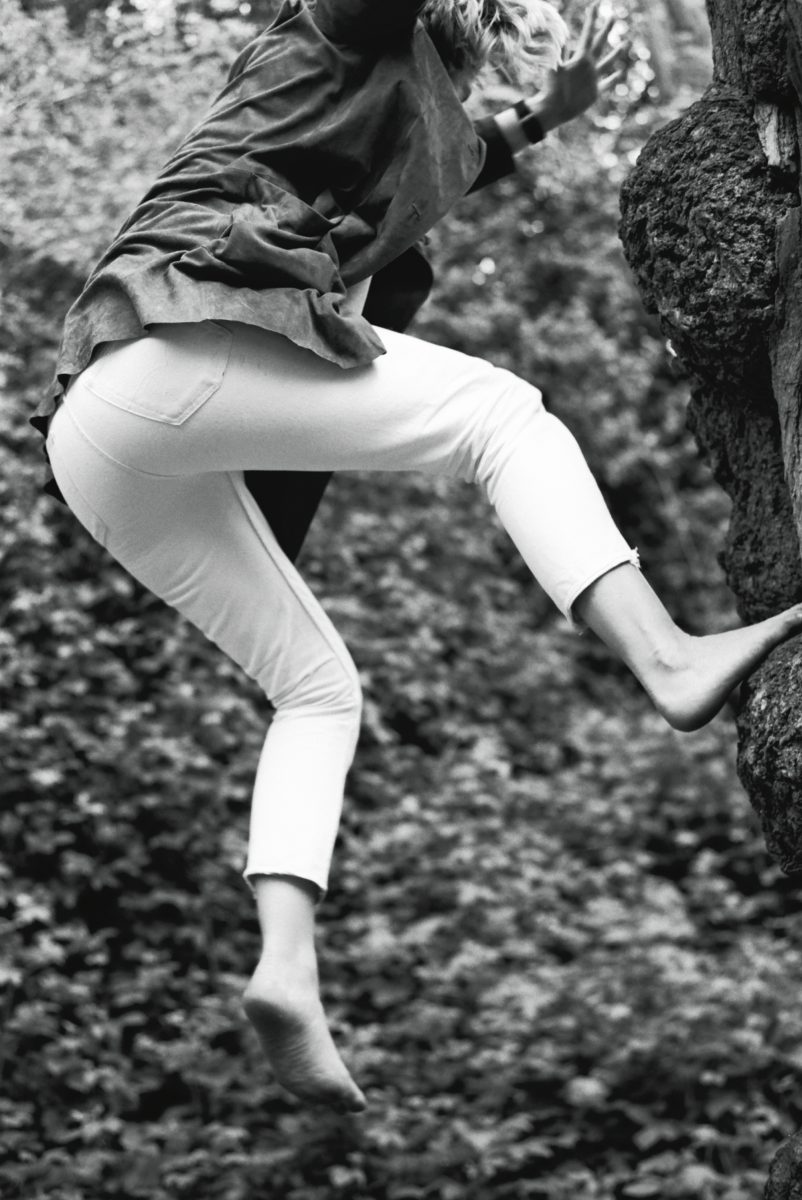

Gesture and motion also underpin Gabby Laurent’s series Falling, which was published as a book last year. Its title hints at gender-specific terms such as the ‘fallen woman’ or ‘falling pregnant’. Laurent is shown mid-tumble everywhere from the public park to her stairs at home. Laurent started the project while experiencing grief, and was later inspired by seeing her baby giving full reign to their emotions. Falling draws on feelings beyond society’s usual strictures, emotions clashing with social norms.

For Laurent, only photography’s ability to capture split seconds in time made the series possible. “I don’t think it could have been conveyed with a different medium,” she says. “The fall is not controlled. It’s messy and more suited to a photographic document.”

“Photography’s ability to capture split seconds in time made the series possible. ‘I don’t think it could have been conveyed with a different medium’”

Laurent felt a photobook also fitted this work, the successive pages lending a repetition that tapped into the humour and absurdity of repeatedly hitting the floor. She created the book with Loose Joints, a Marseille-based publisher founded by Lewis Chaplin and Sarah Piegay Espenon. The pair have published numerous photobooks that engage with performance and the self, from Laurent’s Falling to the staged scenes of Mohamed Bourouissa’s Périphérique to the choreography of Luis Alberto Rodriguez

’ People of the Mud

(both of which use third parties to perform).

- Both: Gabby Laurent, Falling, 2021

Chaplin and Piegay Espenon have now teamed up with Maher & LeWitt Studios to launch an award called Publishing Performance, which will see one artist take up a residency at Mahler & LeWitt Studios in Spoleto, Italy, to create work that Loose Joints will help publish as a book (alongside an exhibition at their Ensemble space in Marseilles, and at London’s Webber Gallery).

The award takes an open-minded approach, encouraging entries from both visual artists playing with gesture and staging, and those who come from choreography and performance and are interested in incorporating visual techniques.

“One can consider all forms of photographic practice as being performative”

“Sarah and I have always been really interested in how performative gestures intersect with photography, and indeed how one can consider all forms of photographic practice as being somewhat performative,” says Chaplin. “Perhaps it is a realisation and engagement with the latter idea that leads certain artists to consider how incorporating idea of performance into their work can help to realise complex social, political or conceptual messages.”

The camera never lies? Perhaps not, but through fiction and performance it might just find its way towards deeper truths.

Diane Smyth is a freelance journalist who has written for The Guardian, FT Weekend Magazine, Creative Review, the British Journal of Photography, and many more

Gabby Laurent images © the artist, 2021. Courtesy Loose Joints

Publishing Performance

A new residency and publishing award by Loose Joints Publishing and Mahler & LeWitt Studios. Applications close 1 March

EXPLORE NOW