On one of many sweltering tube journeys from the west of London (where I live and work) to the east (where the large majority of artists live and work), I found myself reading an advert for an online dating agency which rather horrified me. It claimed the company had “cracked the code of lasting love”, inviting you to sign up, pay them a fee and answer 150 questions about yourself before magically finding the love of your life…

Firstly, the thought of answering 150 questions filled me with utter horror, and secondly I was left with an uneasy feeling that there must be people (a lot of people) willing to hand such a personal and intimate part of their life over to a set of algorithms in the hands of a corporate, profit-making entity. It made me wonder: what has happened to real human connection, and why do we seem so eager to let the data giants tell us how to create it? It seems something is off-kilter in the way we are currently interacting with each other.

As we make plans for the opening programme of Elephant West, I am thinking about ways in which we can bring people together for real-time, analogue experiences that connect us to each other. In a week when Boris Johnson described burka-wearing Muslim women as “looking like letterboxes”, and a report was published claiming we are fast heading for “Hothouse Earth” status, the time to collaborate and learn from each other has never been more urgent or important.

“What has happened to real human connection, and why do we seem so eager to let the data giants tell us how to create it?”

In this spirit of cooperation, we recently held our first gathering of a group of artists who will be creating a project entitled Welcome Home next year. The project considers how we will be living in the (undefined) future—where will we live, what role will the home have in society, and who will live there? Two of the participating artists collaborate with scientists as a core element of their practice; Amanda Baum and Rose Leahy create beautiful, tactile, interactive installations that consider our micro-biology. They see the home of the future as being a place to heal, restore and rebuild our microbiomes. Their installation will encourage audiences to interact, touch, and feel the various elements within it; bringing our awareness to the visceral quality of being human.

I was recently asked to host a discussion with a wonderful artist, and winner in 2012 of the first ever Griffin Art Prize (which we are joining forces with this year for the first Elephant x Griffin Art Prize), Alzbeta Jaresova, known to her friends and colleagues as Betty. The discussion took place during her solo show at Velorose Gallery near the Barbican in east London; a moment that I was extremely proud to be a part of, having remained connected to and supported Betty for several years. These kind of connections are so important to me, and to the success of the programmes we run; they are genuine and lasting, based on real-time conversations, professional support and (perhaps most importantly) friendship. The public conversation we held at the gallery allowed that friendship to open out and invite new people into it; the audience became part of our circle for the evening.

Having spoken so strongly in favour of real-time and analogue, I am now going to flip things around a bit and tell you about an interesting virtual experience I was invited to participate in, created by the Russian artist Uliana Apatina. On her website, Uliana asserts “new art must be… immersive, site-specific, disorienting, interactive”, and the experimental piece she invited me to see certainly met these criteria. It was also in a small room tucked into the rafters of a rather airless studio building on one of the hottest days of the year, so it was an altogether bodily experience.

“These kind of connections, based on real-time conversations, professional support and (perhaps most importantly) friendship, are so important to me, and to the success of the programmes we run”

Entitled Brain AI, the project requires the participating audience member to wear various electro-receptors, on the head and hands, which measure and capture data relating to your reactions and responses, and in turn feed back into the work as it develops. The piece blends the virtual with the real, through a VR headset, immersing you in a forest of fast-moving cylindrical shapes that increasingly encase your body as you move around the space. Rather unnervingly, some of them appear as real, solid objects in the room that you can reach out and touch.

Uliana told me she is working with a coder to develop this piece into a large scale public installation, building in and working with the data she collects during these early experiments. What was interesting about it, for me, was the way this artist is immersing herself into a complex new technology and learning to use it as a tool to explore human reactions, feelings and desires. In combining the virtual and the real, albeit slightly clumsily at this early stage, she sets up a disorienting situation that ultimately asks you to consider your relationship to technology, the virtual world and the real world in which we live and breathe.

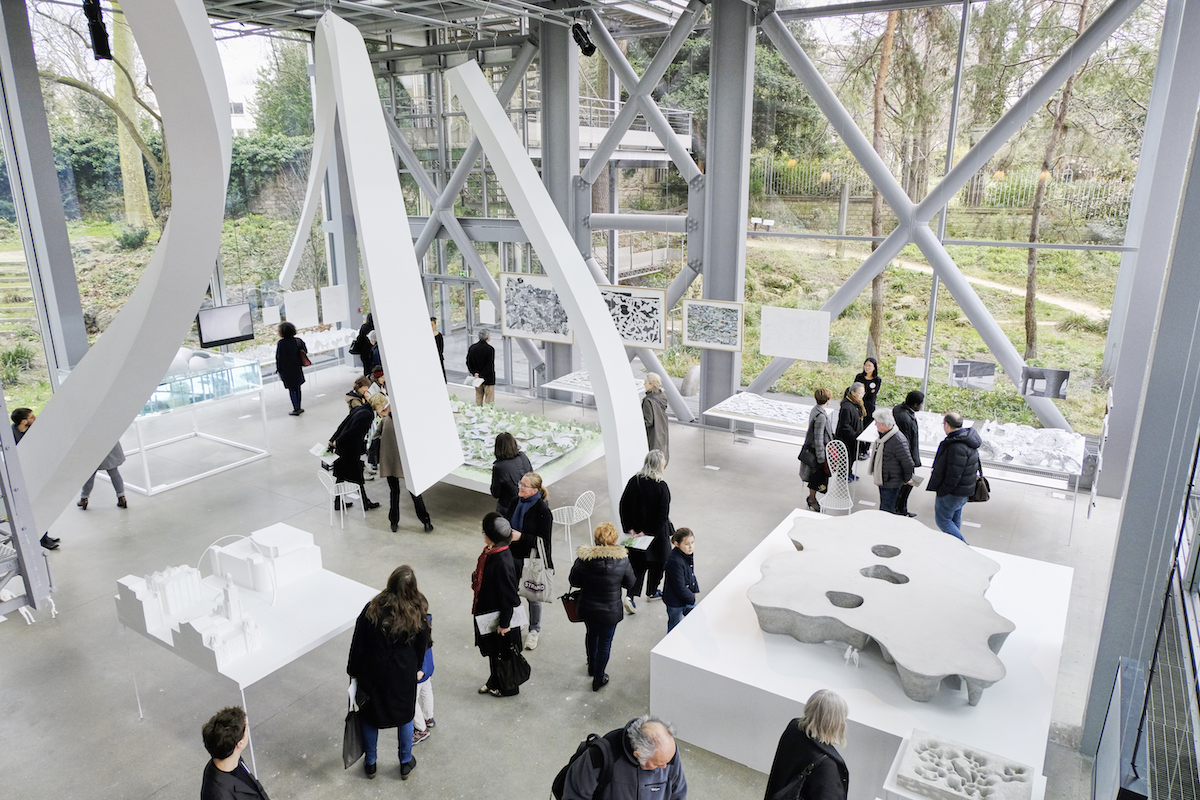

During a recent conversation with Kate Mulcahy, who runs the Makerspace at Imperial College’s Invention Rooms (which I mentioned in last month’s column), she talked about the need for young people to learn about creative thinking, hand skills and imaginative making. These things are continuously being stripped out of our education system in the UK, in favour of more “measurable” skills such as coding, science and engineering. I couldn’t agree with her more, and on a recent visit to Fondation Cartier in Paris I saw the perfect example of the importance of imaginative making in an exhibition of the Japanese architect Junya Ishigami.

“In combining the virtual and the real, she sets up a disorienting situation that ultimately asks you to consider your relationship to technology”

Whereas most architecture exhibitions involve digital renderings and blueprints, shown alongside meticulously produced 3D models, Ishigami demonstrates his extraordinary range of skills and expansive imagination through paintings, drawings, sculptures and experimental models, almost all made by hand. It was clear to see that Ishigami’s process is akin to that of an artist; three-dimensional experiments, hand-painted ideas and playful drawings often eventually lead to extraordinary pieces of architecture, but they are also beautiful and meaningful pieces of work on their own.

Summertime is festival time in the UK, and if you want to feel connected to your fellow humans, be creative, dance under the stars and run about adorned in only glitter and feathers then there is nowhere better to be than one of the thousand-plus festival events throughout the UK each year. I went to Noisily in Leicestershire and Wilderness in Oxfordshire this year, and came back from both with a renewed sense of connection to the world (and seemingly forever glittery). I would love to be able to create that kind of feeling with our audience at Elephant West; a year-round festival of creativity, fun and freedom under one roof… And I promise we won’t require you to fill in any 150-question-long surveys to be part of it.