Hato is a welcoming place, and a comfortable one; not least because of its shoes-off, slippers-on policy. But this isn’t a gimmick or tokenistic bid for employee “wellness”: it’s a nod to the studio’s Japanese-inspired approach, which subtly underpins its processes as well as its name and logo. Hato means pigeon in Japanese, and so the company’s mark is a dove, rendered in painterly, almost calligraphic, brush strokes.

The studio was born at the end of 2009 when cofounders Ken Kirton and Jackson Lam were fresh out of Central Saint Martins, beginning with a single risograph printer and a determination to create work from the standpoint of involving clients and the wider public as collaborators and “co-creators”. Lam now helms Hato’s outpost in Hong Kong to focus on work out there for galleries like the currently under-construction M+; while Kirton remains in London.

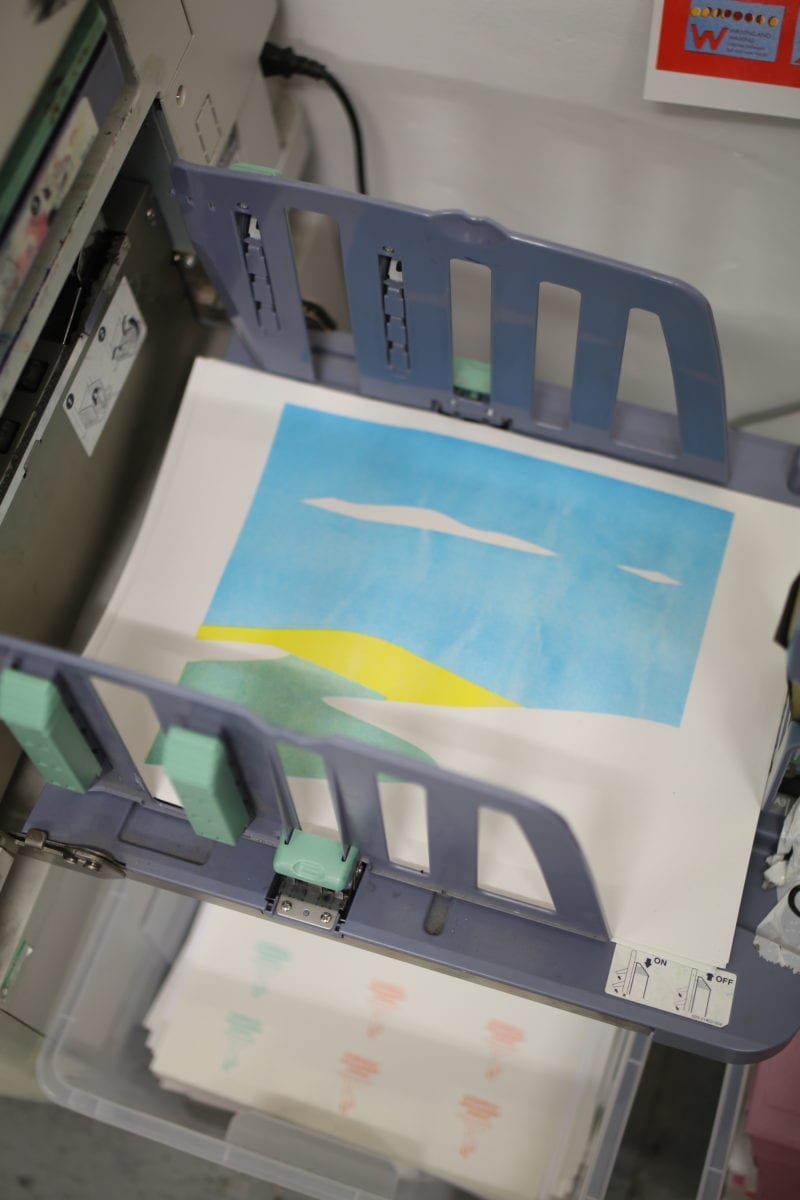

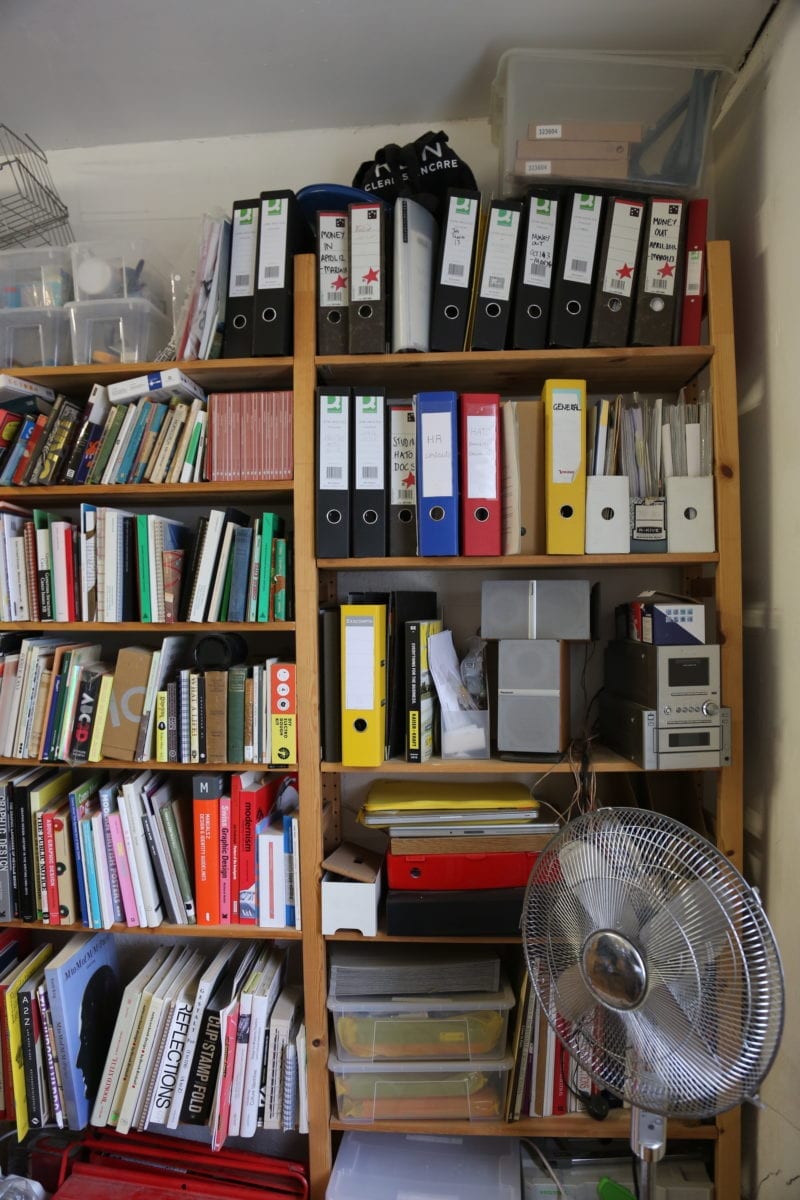

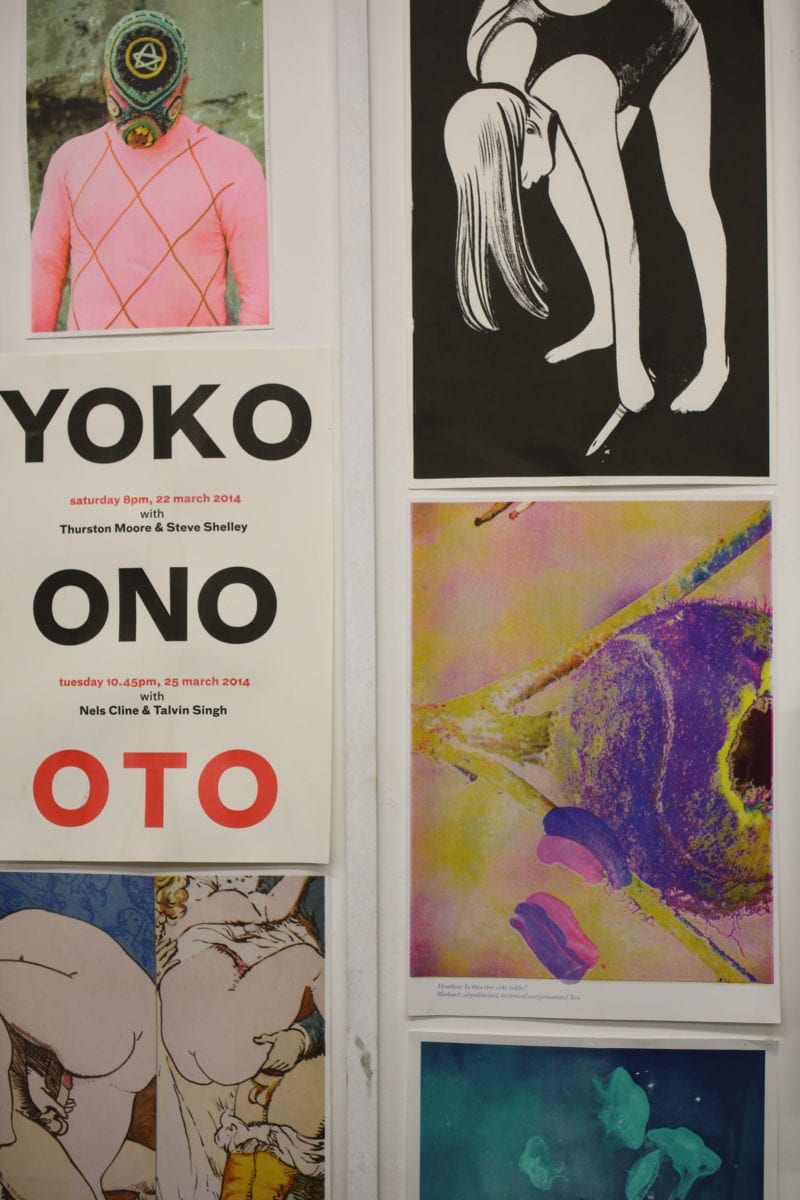

Today, Hato is a sprawling entity, though one that feels entirely united in approach and often in aesthetic: Hato Press, which is based downstairs in the studio nestled just off east London’s Hackney Road, encompasses the Risograph printing studio that sees the team print publications and posters for clients (recent projects have included artist editions for Studio Voltaire) and also run workshops.

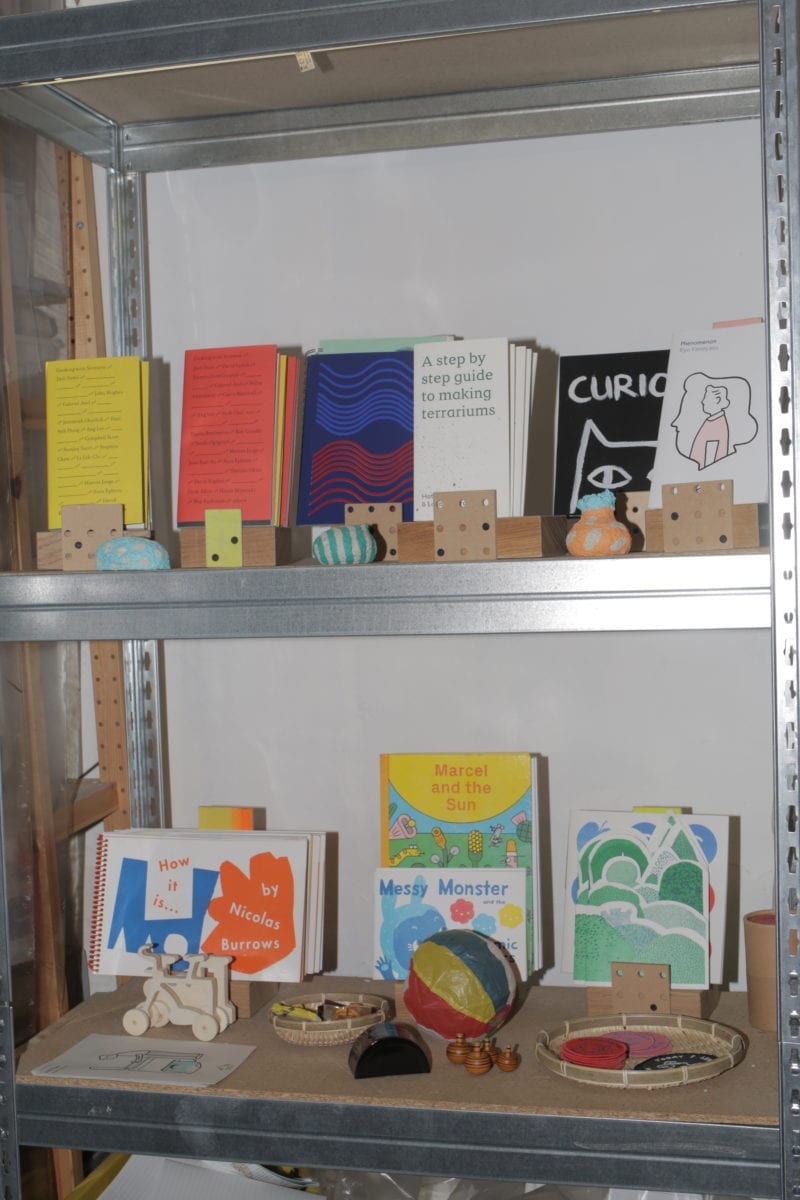

Their publishing arm is also based there, and puts out books ranging from whimsical illustrated tomes by Jean Jullien to the Cooking With Scorsese series, a recipe book of sorts that delineates meal prep through film stills rather than the tired old “200g of butter,” “gas mark 6” formula. There’s even a shop, selling products created in collaboration with illustrators and designers such as cards, stationery, and the occasional rather lovely bum-bag.

The other side of Hato—the upstairs, slipper-wearing half—is its eponymous studio, which has created work for London clients inducing the V&A, Serpentine Galleries, the Design Museum and Somerset House. “The reality of it is that everything is a part of Hato—what we do with design and what we do in terms of printing are all under the same sort of vision, the notion of reconnecting people to creativity,” says Kirton. “So in the digital studio, that’s building digital tools to help connect people to that creative space; but the workshops with the printing presses are a tool or project space in the sense it exists to allow people to have accessibility to that means of production.”

The studio’s focus on working with cultural clients is down to a couple of things: one being that the first project they landed was The Serpentine Galleries’ ongoing Edgware Road Project, which brings together artists, residents, shop-owners and other locals to the area to “investigate, activate and imagine futures for the Edgware Road” through co-creating printed publications.

The main reason, however, is Hato’s progressive, unusual and inclusive approach to design; which is underpinned by “co-creation” rather than the usual “here’s a brief, off you go, revise, sign-off” process—something that (historically at least) arts clients have had more faith and interest in than those on the commercial side.

The co-creation approach, again, partly comes down to the studio’s admiration for Japanese culture. “It’s a very community-centred society,” says Hato cofounder Ken Kirton, whose mother is Japanese. “That’s something we really respect and try to apply to our projects and the way we work with people.” That means everything from the idea of seeing clients as “collaborators”; to being encouraged to refine a particular craft or skill.

“It’s about the notion that everyone has a specific role, and we each do that to the best of our capacity,” says Kirton. “If everyone’s doing that, there’s more of a community aspect to it.” It also means Hato staff take it in turns to cook lunch for the rest of the studio every day. “Lunch is a social interaction, and there’s a sort of art or symbolic element to cooking for everyone and sharing from the middle of the table,” says Kirton.

“A printing press isn’t just a space where you get something printed—it can a way of engaging a community”

Hato is now beginning to work with brands as well as cultural institutions: a recent standout project is their website design for London restaurant Sketch. It’s a bonkers yet brilliant platform that mirrors the eatery in its intricately detailed and high-end loopiness, and in the individual spaces: the section for the Gallery (the part of the restaurant that serves afternoon tea) lives digitally as a surreal game of food Tetris, for instance; while The Glade encourages visitors to make a digital grass rug grow.

“Some commercial clients are becoming just as brave as cultural ones,” says Kirton. “Our clients have to have a lot of trust in us, as often we don’t have a clearly defined outcome—they sign off on a process, and a visualization of what that might look like, then we go backwards and build everything.”

A project that exemplifies this joyfully playful, unpredictable approach is Hato’s 2018 Start With a Mark campaign for D&AD. The studio developed a 3D digital tool and invited the public to submit their doodles, in doing so co-creating the visual identity for D&AD’s 2018 activities. Marks were first displayed in an online gallery, with a selection of those submitted going on to be used across the organisation’s collateral, including 3D animations and environmental graphics for April’s D&AD Festival.

Hato’s emphasis on co-creation is also informed by the idea of “experimenting with what could a printing press could be,” says Kirton. “It isn’t just a space where you get something printed—it can a way of engaging a community.” That methodology is in part inspired by pedagogue Célestin Freinet, who would often take children on exploratory walks in which they’d choose a subject (a certain tree, perhaps), research it, then typeset and design a printed publication around it. “That became a really nice eye opener in terms of what we could do with the risograph printer”, says Kirton.

The cofounders’ love of the Arts + Craft movement has also had a huge impact: “The movement was inspired directly in relationship to the industrial revolution, and when we graduated it was very much the digital revolution,” says Kirton. “In utopian texts like William Morris’s News from Nowhere, craft is seen in terms of the human element.”

Words: Emily Gosling

Photography: Louise Benson