There’s a fairly established way in which we hear about the lives and stories of marginalised people. In many, if not most cases, they’re mediated by someone more privileged, with greater access to resources or power or a platform. Journalists, NGO workers, or artists work to shape, direct and curate certain narratives, which are then presented as “genuine” looks into the lives and minds of people who often live far away or in very different circumstances. The stories are invariably transmitted through the lens of the outsider, whose access and views affect an audience’s impression of their subject.

These kinds of intervention may be useful: they can shed light on distant political realities, and can help make real other lives and parts of the world. Wendy Ewald’s latest book, The Devil Leaving His Cave

, treads ground both familiar and strange as the photographer navigates creating space for a community to tell a story about itself while also overseeing her own narrative.

In 1991, Detroit-born Ewald travelled to Chiapas, a state in Southern Mexico, where she taught photography classes for Tzotzil Maya and Ladino children living in neighbouring communities. Almost 30 years later, in 2020, she repeated the exercise with a (virtual) classroom full of students in Chicago’s Centro Romero, a legal aid and community organisation founded by Salvadoran immigrants.

The Devil Leaving His Cave is a collection of photographs by both sets of children, accompanied by words from the children themselves. Musings, stories, ideas or theories they have about the world and how it works are sometimes closely related to the photographs, but are sometimes only linked because they were produced by the same child.

In an essay accompanying the images, Ewald explains the meaning that photography had for the communities in Chiapas. “Mexican villagers had been seeing cameras and video camcorders for years,” she writes. “Yet photography has always spoken with the accent of the culture that claims the camera. I thought it best to not take any pictures of my own and instead work with my indigenous and non-indigenous students while they made photographs of their own.” Photography seems to be less about learning things, as the father of one of the children from Chiapas said in an interview, but rather about finding ways to tell and retell the stories they are told or they dream up.

In Chiapas, one of the things Ewald asked the children to focus on were their “dreams or fantasies.” The accompanying photos have children dressed up in masks, including the aforementioned devil coming out of his cave and spying on girls atop a tree; a woman in a chicken mask hanging her laundry out to dry; river monsters rising from the mist. The accompanying text also dwells on dreams. Children explain what happens to you when you die, when you dream, when you imagine things.

“The accompanying text also dwells on dreams. Children explain what happens to you when you die, when you dream, when you imagine things”

The photos, which are shot on Polaroid positive/negative film that Ewald describes as “so deliberate as to be awkward,” carry over some of that dreamlike quality. Many of the pictures that show everyday activities (“my sister weaving; my uncle Mariano is working in the field; my dog walking in the patio”) nevertheless have the soft-focus blur of a dreamscape. Even with the strangeness inherent to the format of film photography (the crisp foregrounds, the hazy backdrops) the photos are direct. People are often centred in the frame, facing the camera, captured in static poses. The focus is on scenes, landscapes, wide-focus vignettes as opposed to details.

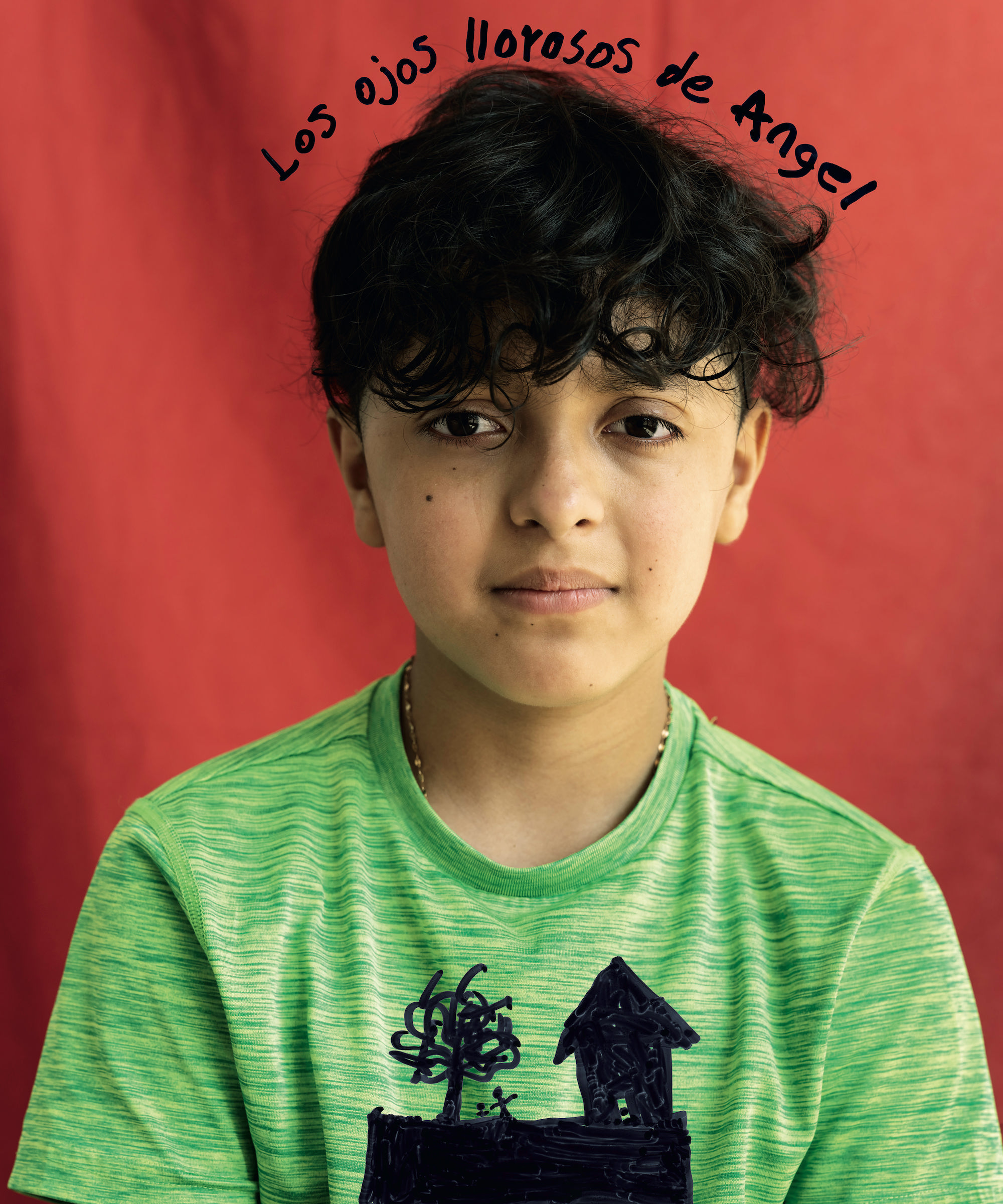

This is where the two sets of photos begin to diverge. While 30 years later, the children of Chicago are still photographing family members, pets, trees and altars, the form and format of the photos is different. Rather than free-floating text and images that occasionally (but don’t always) correspond to the speaker, the updated project consists of mini-profiles of each child in full colour. Each is anchored by a full-page headshot, doodled and decorated by each child, and some text, sometimes even directly narrating the surrounding images.

“It treads ground both familiar and strange as the photographer navigates creating space for a community to tell a story about itself while also overseeing her own narrative”

The Chicago photos are more likely to be of details as opposed to scenes: snippets of an ad, interesting shadows, a set of cards from a lotería game spread out on a tabletop. Ewald writes in the introductory essay that during the Chicago period, she was more concerned with the question of “home,” asking children to reflect on and react to a concept of home shaped by immigration.

It is in this divergence that Ewald the curator begins to emerge: not just the thematic cohesions between the two groups and their various overlaps, but in their placement alongside each other in the same book. The children involved in the project have very little in common other than having kinship ties to similar parts of Mexico.

Ewald gestures towards Chiapas’ status as a through-state for migrants from Central America, linking the 1991 Chiapas children’s dreamscapes to the everyday Chicago photographs. In this, she elides questions of art making and method in the latter group’s photos, presenting them instead as simple documentary.

“Musings, stories, ideas or theories they have about the world and how it works are sometimes closely related to the photographs”

Allowing children to present their dreams gives them a stage to collaborate and create, showing the world something that only they can: not by virtue of their social positions, or their culture, or the context in which they grew up, but simply because only they have access to the strange little landscapes inside their own heads. Asking children who know themselves to be marked by displacement to reflect on their idea of what “home” is, is to ask them to reflect on a site of their difference. It is, in a sense, to represent that difference, rather than the children themselves.

The disjuncture between these two questions might have worked with a stronger editorial or curatorial hand, one that better explained the necessity of these two projects appearing alongside each other then drew out and examined their connections and divergences more carefully. Instead, we have children grouped together across decades and a loose sense of geography, but with nothing in common except their attendance at one of Ewald’s workshops. And that accented lens creeps in.

is an essayist, embroiderer and translator. Her profile of Wangari Mathenge appeared in Elephant’s Spring Summer 2022 issue

Wendy Ewald, The Devil is Leaving his Cave, is out now (MACK)