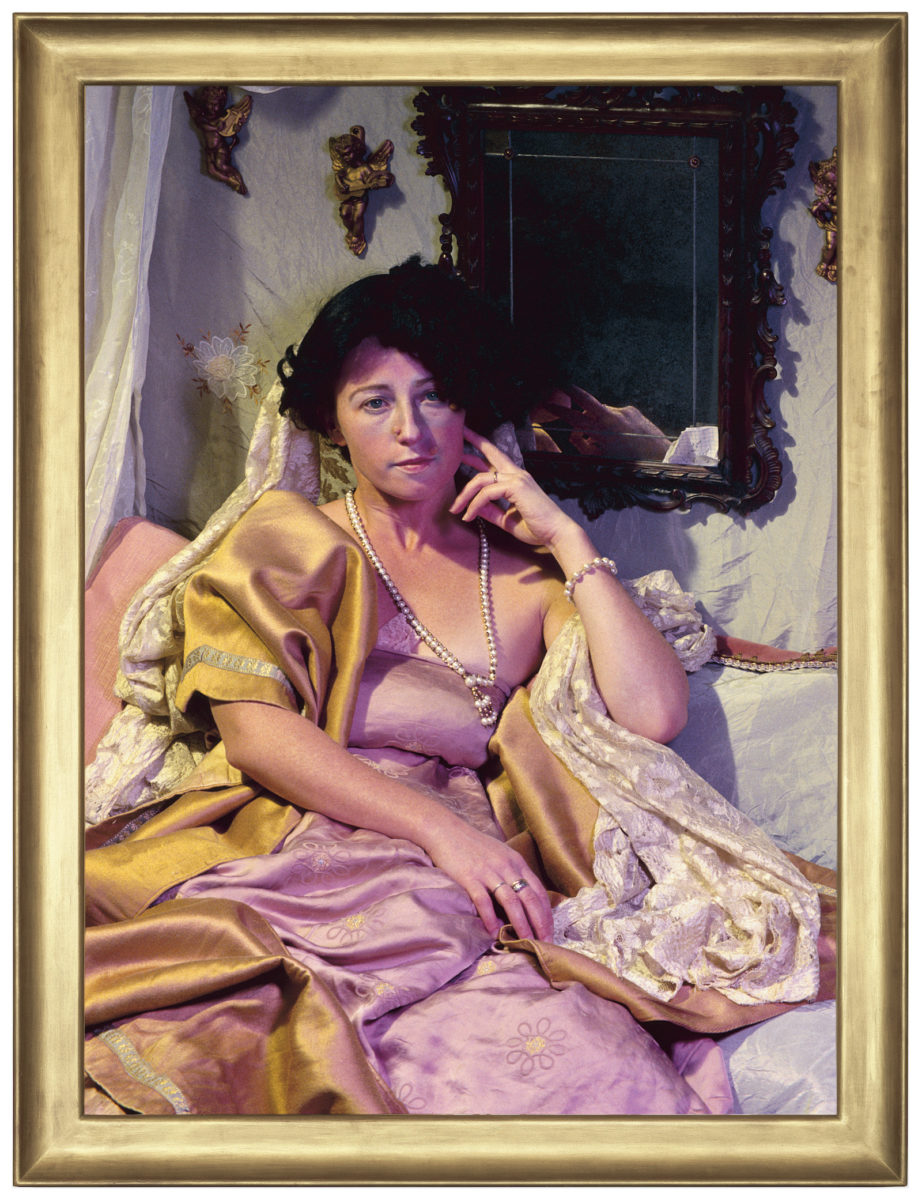

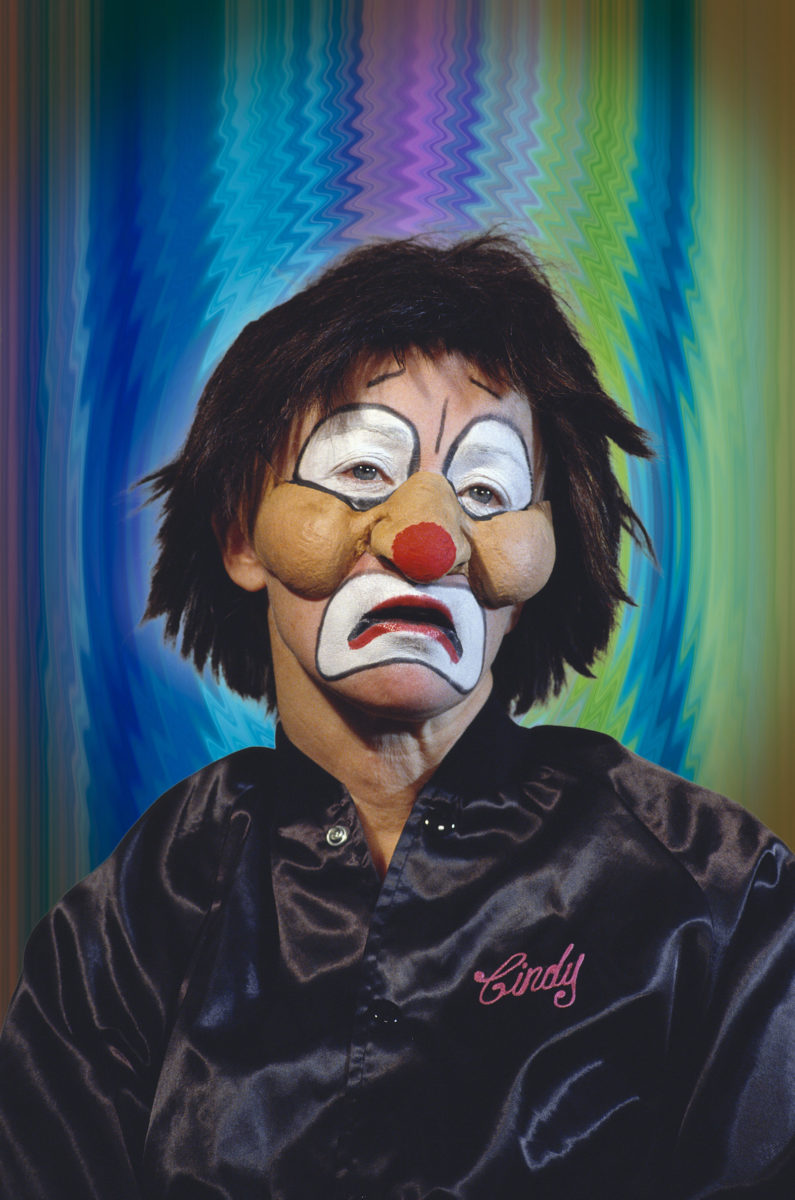

Sometimes when I look at Cindy Sherman

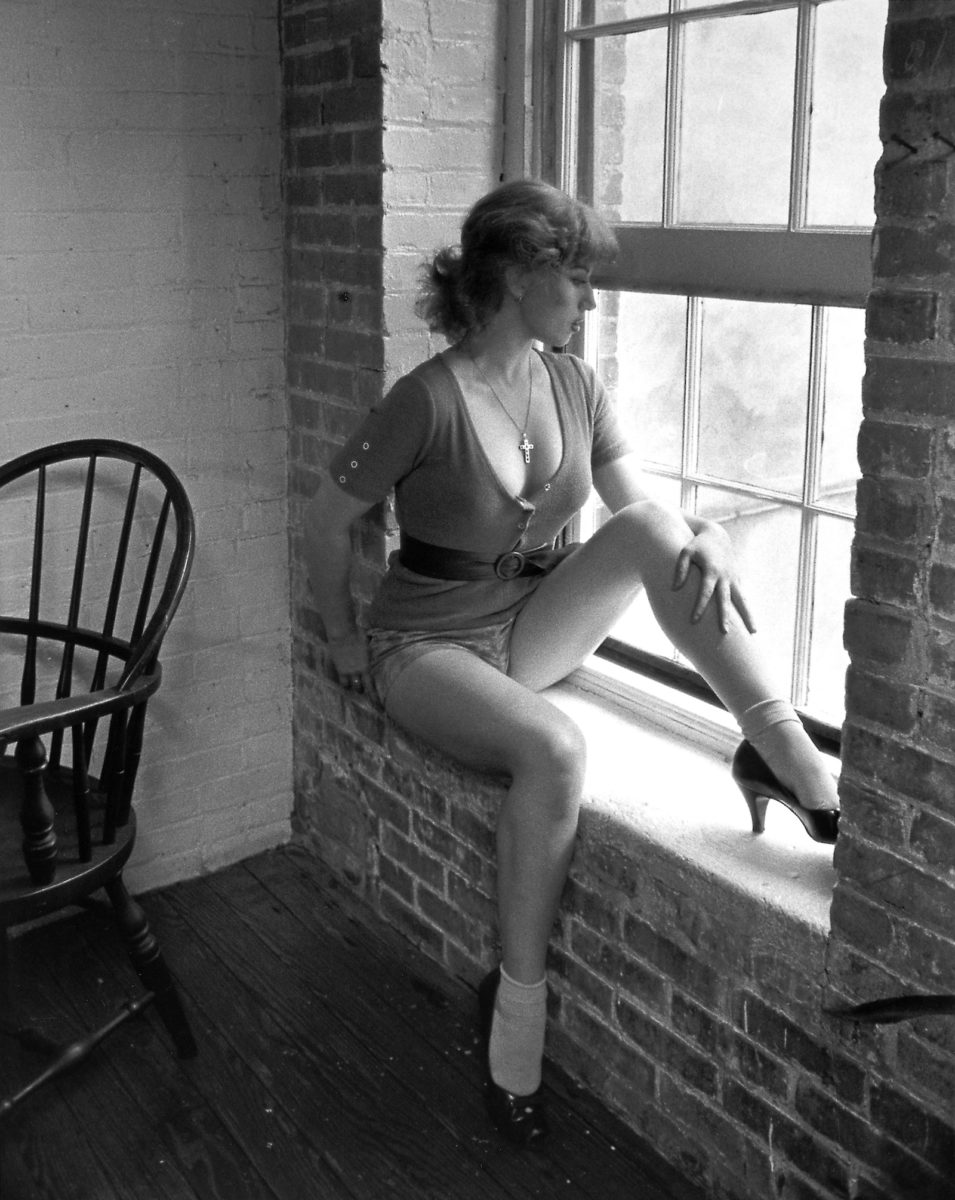

’s self-portraits as other people I wonder if she likes women, or even being a woman, at all. She is often so brutal towards her subjects—complicated by the fact that what we’re always looking at is also the artist herself. Sherman doesn’t engage in talk about her art, and when she gives interviews, the narrative is always the same: youngest child of a parochial-minded family, older parents, quiet, unconfident and obsequious until she hit her teens and eventually moved to New York, intrigued by its glamorous image. There are no titles to the images, so we have to think for ourselves.

It’s obvious why Sherman, now wealthy and in her sixties, living with her macaw in New York, has been so popular with the generation that followed her. In fact, we can probably learn more about Sherman now by looking at the artists she’s inspired, than from the artist herself. Her images are so famous that there’s little space left for new ideas about them. Sherman the ultimate anti-portrait portrait artist, whose deliberate reconstructions and pastiche make us all into grotesque and absurd puppets of consumerism. There’s humour, sure, but the overwhelming feeling in Sherman’s pictures—and the reason she’s been interpreted, for so long, as feminist—is that it’s pretty shitty to be a woman. Look at what we have to do to ourselves! Look how ugly we become! This is what society does to us! This is what the media turns us into! But we are also very much implicated in this. Sherman is as much complicit in this as the viewer-consumer.

“There’s humour, sure, but the overwhelming feeling in Sherman’s pictures is that it’s pretty shitty to be a woman”

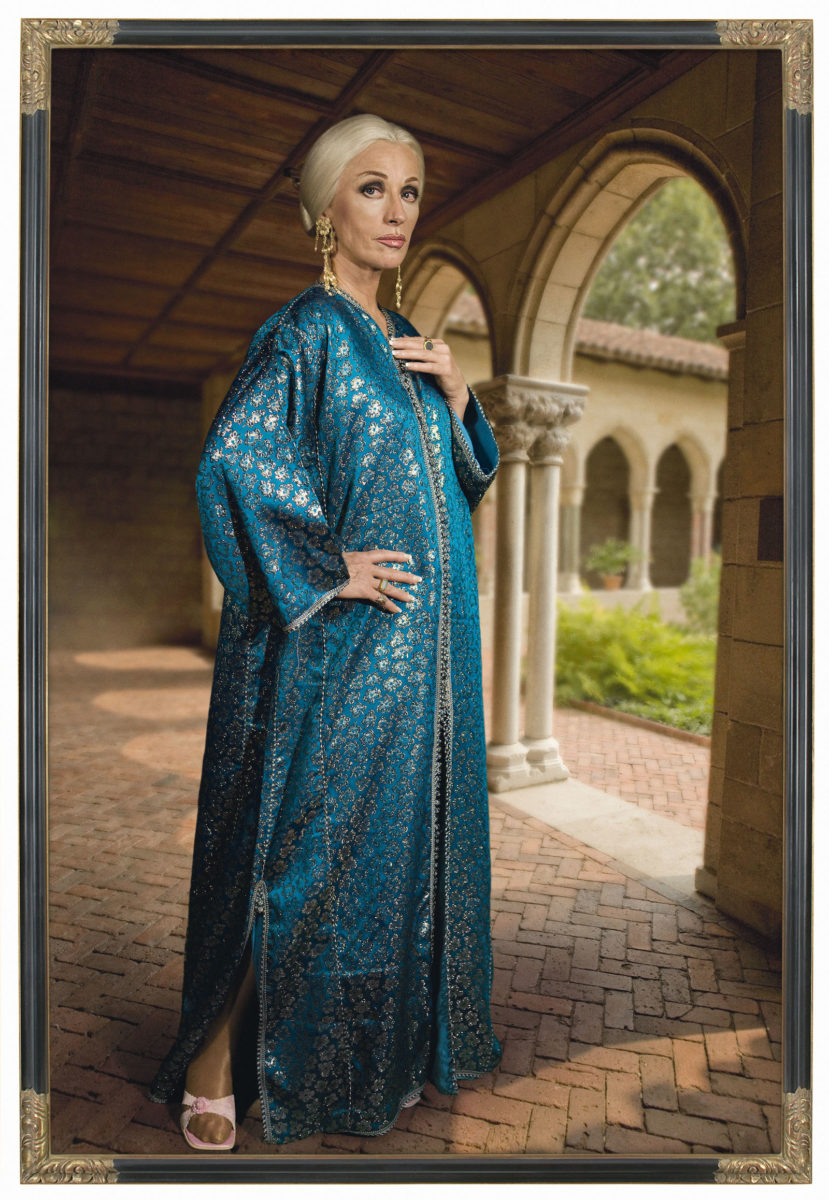

In her most recent works, including some of her Instagram portraits, Sherman has addressed the question of ageing directly: she’s cast herself again as stars from the Golden Age of Hollywood, but imagined decades on: Sherman has admitted that she has struggled with ageing herself—both in terms of health, and in her appearance—the physical changes all the more obvious as she’s so used to seeing herself up close, on a daily basis. She’s spoken openly about the cosmetic surgery she’s had. All of this has undoubtedly had an effect on her work: “What is disturbing is not seeing more lines of my face but seeing that the range of possibilities of what I can do is much more limited.”

Sherman’s source material has always been the mainstream media, and their portrayals of women and stereotypes of femininity—enlarging them to an absurd degree. They have to work because we know those sources, and the work makes us feel awkward about them. In an age-obsessed culture, Sherman was still able to infiltrate images that mythologized youth and beauty. As Sherman has got older, though, there are fewer references for her to draw on—given the lack of representation of women over fifty in film, advertising and in visual culture. Society wants to forget women when they hit the menopause, and just as it’s harder for Sherman to be against the establishment when she is now so much a part of the canon, it’s difficult for her to critique age when there’s no image to deconstruct. Perhaps what makes her recent work even more frightening is exactly this antipathy towards ageing, from within.