With the growing popularity of American TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race, the art of gender performance has been steadily gaining greater prominence on the radar of mainstream consciousness. However, there’s more to drag than queens—drag kings are just as worthy of our attention.

According to American photographer Del LaGrace Volcano, the drag king scene really got going in the mid-1990s when the first drag king contest was held at the London Lesbian and Gay Film festival in 1996. Through competing in this contest, Volcano met gender studies academic Judith Jack Halberstam and the pair went on to produce The Drag King Book in 1999, featuring over one hundred photos of drag kings from across the globe, who demonstrated that performing masculinity is just as compelling as performing femininity.

These days a new generation of drag kings are continuing Volcano’s work, showing that performing drag is not just playing dress-up. Vincent Honoré’s 2018 Hayward Gallery exhibition Drag: Self Portraits and Body Politics explored drag as a political performance, with the curator explaining his belief that “drag goes beyond gender to approach something that is a different way to be human”.

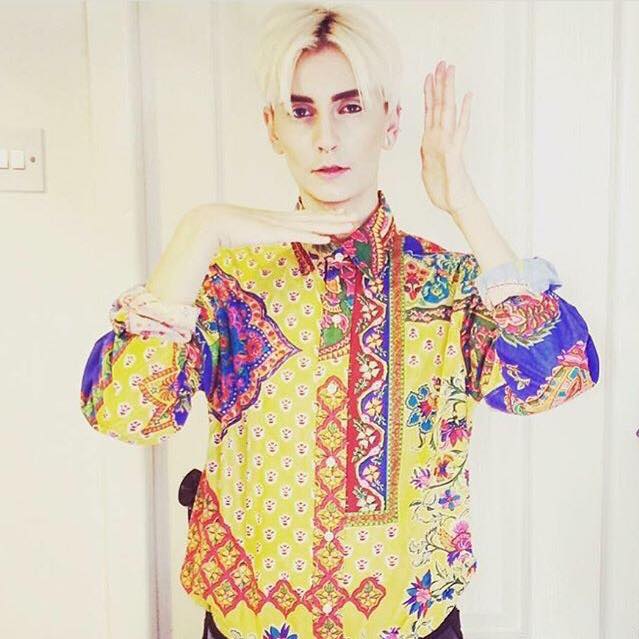

- Left: The Pecs: Victor Victorious, Cesar Jentley, Thrustin Limbersnake; Right: The Pecs: Mr Goldenballs, Drag King Cole, John Travulva Photos by Rah Petherbridge

“Drag is not just about gender, but about a different and more inclusive way to be human”

Many drag performers recognize this belief; while their exaggerated performance of gender may not mirror where they fall on the gender spectrum, their alter-egos greatly reflect—and indeed sometimes help them to discover—who they are as people. In fact, numerous drag performers have stated that traditional gender roles have very little to do with who they are, with many (although not all) identifying as non-binary or gender-queer and going by they/them pronouns. As Honoré explains, drag is not just about gender, but about a different and more inclusive way to be human.

Jen Powell, founder of Boi Box (a monthly London space for drag kings) performs as Adam All. Speaking of All, Powell says, “He has different mannerisms, a different energy and a completely different backstory to me, but we have similar goals and beliefs. He’s such a constant in my life, he can’t be that different from me really.”

Kit Griffiths, who performs as host Cesar Jentley in drag king collective Pecs, agrees. They believe that despite Cesar’s New York accent and turbulent origins, his personality is nonetheless a part of them, saying “My ‘character’ of Cesar hugely relates to who I am as Kit out of drag—confident, conflicted, loving, flawed—all of it is real.”

Anyone wanting cabaret, camp and crooners will find what they’re looking for at Boi Box, King of Clubs or Pecs’s nights at The Yard. And for some drag performers, that’s what it’s all about—the audience is looking for a good night out and drag kings offer it to them in a myriad of theatrical performances. Karen Fisher, who performs as King Frankie Sinatra, argues, “Drag kings definitely have a political role to play but for me it is primarily about being entertaining.”

You just have to look at some of the drag king names—among them Thrustin Limbersnake and John Travulva—to see that entertainment is an essential intention of drag. However, it also offers performer and audience alike the liberating opportunity to confront and question society’s accepted gender roles even while maintaining the feeling of fun.

“Drag kings don’t just interrogate masculinity, we celebrate it, too—and the world at large needs to do both”

Powell says, “At the root of my drag is a battle with misogyny. I’m aiming to literally demonstrate that we are all capable of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ and that placing these concepts as opposites is part of a flawed and oppressive power dynamic. But I’m doing it with a light-hearted humour nonetheless.”

Griffiths believes that this light-hearted humour is in fact conducive to drag’s political message. They say, “Play is the first way we learn in life, and the best—the fact that our drag performance is fun is directly linked to how much we and our audiences are learning at the same time.”

Ben, who performs as Benjamin Butch, believes that drag king culture is about celebrating versatile masculinity as an important and universal aspect of identity. He says, “Masculinity is felt and explored and expressed differently in each person and it’s nice to see masculinity from different perspectives.”

Griffiths argues “Drag kings don’t just interrogate masculinity, we celebrate it, too—and the world at large needs to do both, to interrogate what is toxic behaviour and separate that from more neutral or positive gender performance, so that we can all start to enjoy and respect ourselves, and therefore enjoy and respect one another.”

The countless ways that drag kings perform masculinity are a celebration of its fluidity and diversity. Ultimately, they draw attention to gender to point out that it is far from the most important thing about being human.

Powell believes that this is the crucial thing to take from drag king performances, saying, “I would like to think that we are a part of a wave of change that helps us all move past our preconceptions of gender roles in society. It would be wonderful to conceive of a world where someone’s gender is not a constant influence on how we treat each other, that kindness and respect come first.”