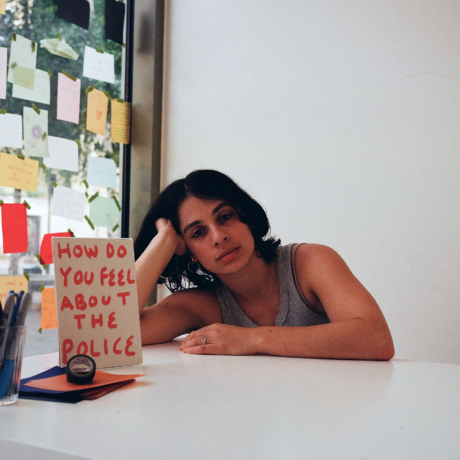

Confessions is a monthly column by Emily Pope. This month she speaks to British-Nigerian artist Onyeka Igwe about collective living.

Everything has been quite wet and slow, and not in an exciting way. I had a soggy beginning to the summer, lacking imagination, writing applications for things I didn’t get last year and wishing I had more time in the studio. This had compounded into a helpless, bitter, competitive depression—the worst kind. Then I decided to try and get over myself, intensified by someone saying to me in passing—for fucks sake Emily, you’re such a critic. I went to Glastonbury with friends, I went twice to a night called ‘Reject All’ (run by Ruth Angel Edwards and Adam Gallagher—the place to go if you want to see the best subcultural offerings from multigenerational artists), I enjoyed the dyke bars popping up all over London, and realised that it’s fine if I lament the Joiners Arms and Power Lunches—younger queer friends will too lament something at some point when everything starts to look new to them. Londoners, despite everything and as cliché as it may sound, have a lot of tenacity.

Given this, I was interested to talk to Onyeka Igwe about her solo presentation, The Miracle on George Green at Arcadia Missa in Soho, bringing together letters, film and sculpture to look at the UK’s tradition of the common—spaces collectively owned and utilised for community engagement, gathering, playing and debating, landing on the George Green treehouse in East London as its focal point. Onyeka’s work delves into both oral and written histories, conventional and non conventional archives, and often overlaps narratives and perspectives with a panopticon approach to deeply political and moving subject matter. Broadly, I felt The Miracle on George Green spoke directly to my mood, imaginatively addressing the complicated collective and personal frustration/hope that the left wing has for the UK.

EP: Are you happy to start off with telling me a story?

OI: Well, it’s been a turning-point week. I’ve been feeling extremely alienated from the world. I’m starting a new job in September and I have anxiety about that. I’m moving into a new phase of life and questioning how that’s going to work with my practice. So I’ve been feeling, yeah, anxious about how I’m going to make work and who I am, fundamentally, as a person (laughs). I had a bit of a strange weekend. I have been doing analysis for a long time, like six, seven years. I started the session and I started it in a completely different way. Every time I go, I usually prepare what I want to talk about on my way to the appointment, and plan to start with this very organized –

EP: Virgo!

OI: Exactly. So I told the therapist that I normally do this and I said, maybe I’m doing it wrong. And she was like, Nothing’s wrong. Do you have a notion of why you do that? And I was just like, because I feel like I have to come prepared. And then she was like, would you like to lie on the sofa? I’m like, yeah, I’ve been thinking about this for ages. I’ve never once laid on the sofa—all my friends do. I thought it would be strange to do that, kind of ridiculous, and so when she asked me, I felt my body wanted to say no. And I laughed, and she said you don’t have to. And I was like but I do. And so I had analysis in the way that you’re supposed to have it. It was about this open and closed thing. That’s been on my mind all this week, how maybe I’ve been very closed and contained as a protective kind of defensive way of being. I’m about to start working on a new show for next year. I think that in analysis the therapist is comparing the openness that I have with making, to the openness I have in life. I have to let people in in social situations too. I think if I would describe my practice, it’s about being open to possibilities of what comes in, like just releasing some control. And I didn’t realize that there’s such a dichotomy between how I make work and how I live. So I guess it’s a story about how I want to change.

EP: I think that’s a great story! Ok, so, you describe, or someone else has described, a lot of your work as counter hegemonic, and your work looks at traditional and contemporary archiving from multiple standpoints. So I wanted to know—what’s your favourite archive?

OI: I had a zine archive, which was basically an archive of surprising stuff that people made when they were kids, when they were teenagers, typically from the nineties. I don’t really have a favourite—I love the feeling you get from zines, of time travel, being next to or in someone’s clothes, it feels kind of amazing—the weird things people keep—so strange!

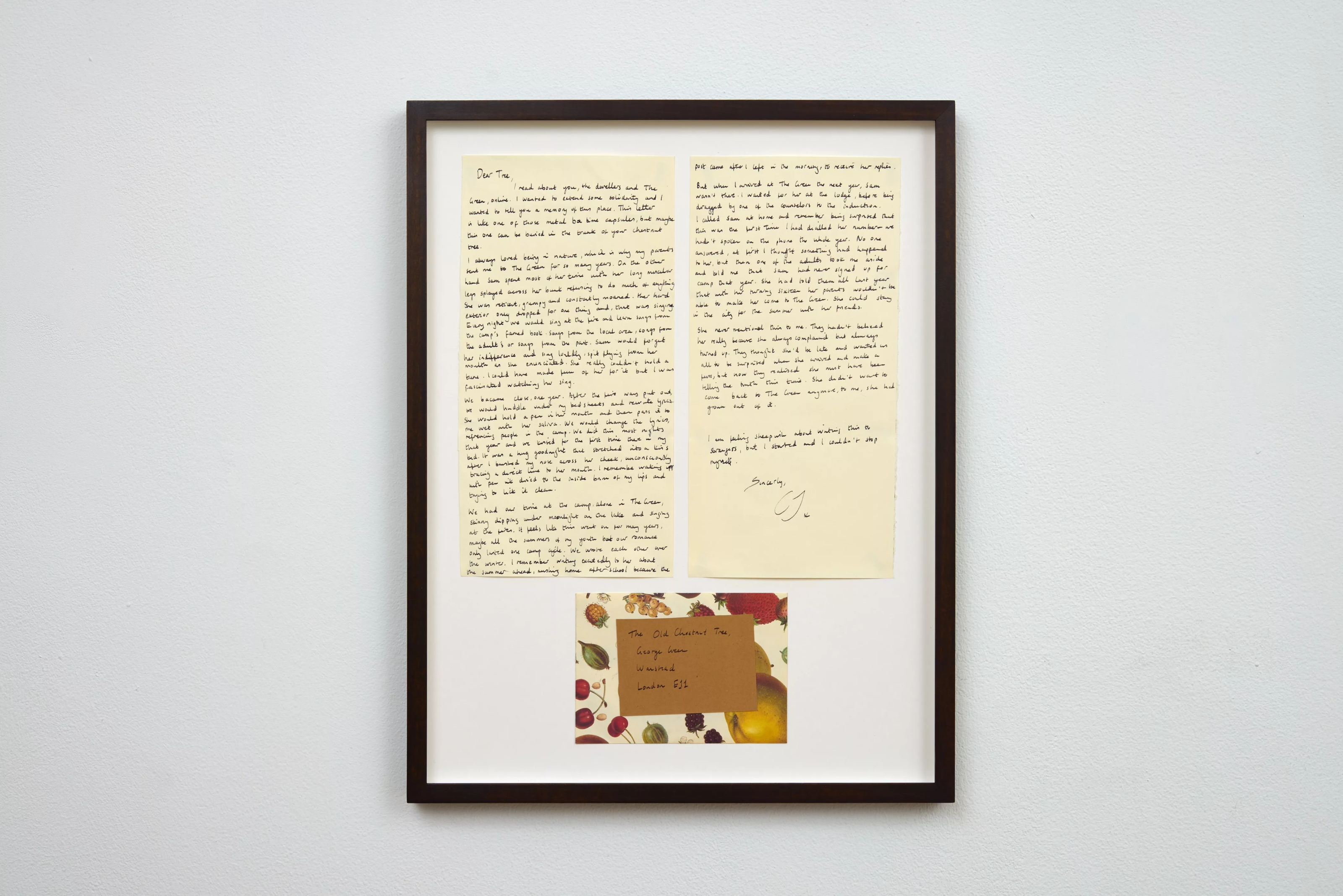

EP: Are the letters in the show real? Can you tell me?

OI: I think it’s fine! I wrote them all! I was researching, what is ‘the commons’ today? What does it mean? I was obsessed with learning about it at school in the English Civil War, wow, we had this kind of, like, proto communist idea, the diggers, all that kind of stuff and I was thinking about how London operates and about how people become politically active. I interviewed people about that—people involved in the George Green Protests, I also interviewed Samuel Delaney because he had this amazing story about coming out, and this really amazing communist camp that he went to when he was very young. So, the letters were kind of drawn from that research and my own experiences, they’re supposed to be the past, present and future of the commons.

EP: There’s another line in your film about this first kiss, this kiss goodnight, and it made me think a lot about squatting communities, left wing communities and the first time you really become active in the left wing community and you have a romance. And that was a departure for me in the film, a totally different space. I was like, oh, that’s really sexy. And I just wondered if there were going to be further works looking at that as a subject?

OI: I’m really glad that it came across as sexy because, I was really worried because, you know, you always read about the worst sex scenes ever…and yeah, I think there is something extra erotic about the meeting of attraction and intellectual and political engagement. There’s always something extra spicy in that. I had two break ups whilst making the film, one of them was from a relationship I had started when I was in the warehouse in this communal living situation and, and he’s actually in the film! I think you’re right. Oh, I never thought about pursuing this, but I think I would like to!

EP: There is another line in the film that really resonated, which was ‘everyone was beaten down and had become strangers to one another’, which exemplifies how I feel right now in terms of what it’s like to try and be a socialist, what it’s like to try and have a common. I wondered what your relationship is to the common now?

OI: That line is reflective of what I was feeling when I made the film, or around the time the film was percolating–2020-22. I was heartbroken about several different things and one of them was this dream of collective living. When I was little I lived in Beckton in a cul de sac and we’d have this incredible street party every year, and once I left that street the memory got sort of frozen in amber as this utopian way of living. Since then, I lived in warehouses and that kind of stuff for a little while and I always thought my future would be in a collective, in a communal house. I was involved in co-op projects for a while, and they always failed. In 2020, a very dear friend of mine who shared this dream with me, left London and moved to Dover and started her own version of it with her partner. I was heartbroken from that. I think that line is about that feeling like this disappointment that this dream that you had isn’t going to be fulfilled. I felt naive. It’s a very sensitive kind of place, but recently I’ve been trying to not be so negative about it and be so binary, yeah, it failed…but that doesn’t mean it could never happen. I want to be a bit more open to the possibility that it could take a different shape from what I imagined. So I mean that’s one way I think about the commons, and I do definitely agree and sympathize with this feeling that certain kind of positions just don’t have a lot of space, but I would say that around Palestine it feels like there is an anti-imperialist internationalist politics re-emerging, and that there is a momentum behind it.

EP: Yeah, definitely.

OI: And I have been feeling buoyed by the many creative and amazing and radical things that people have been doing around that for a sustained amount of time.

Miracle on George Green is on view at Arcadia Missa, London 6 June – 31 July 2024

Word by Emily Pope