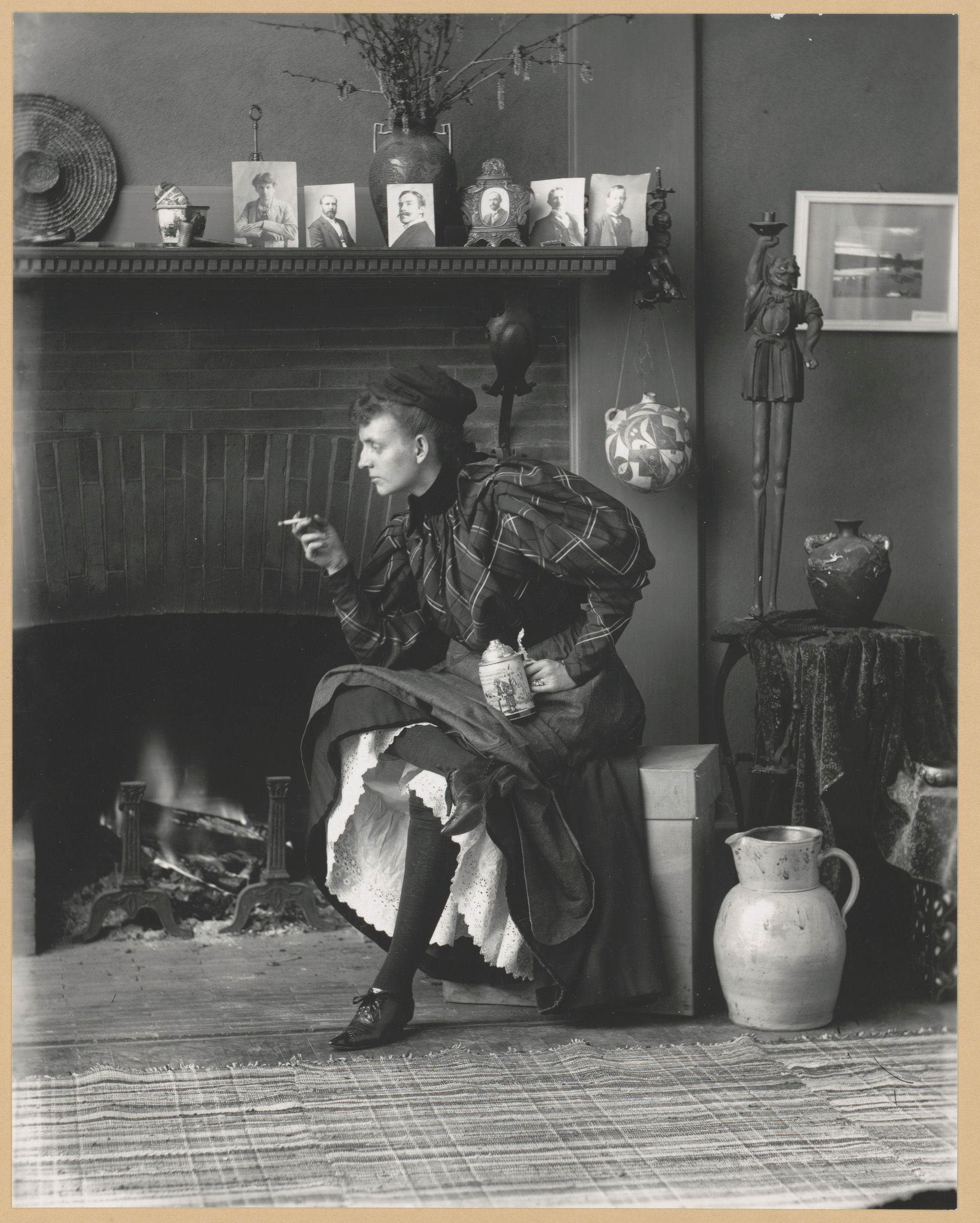

Frances Benjamin Johnston

About two-thirds of the way through her engaging new book, Emma Lewis describes the subtle yet significant distinction between ‘seeing’ and ‘looking’. Photographic theory, she writes, has typically focused on the latter, which positions “making or regarding photographs as an acquisitive act, and the subject as a spectacle”. Bringing ‘seeing’ into the equation introduces a different dynamic: “It suggests that behind the act of photographing is an intention to understand and, perhaps by extension, a will to help the viewers themselves feel understood.”You could say that Photography: A Feminist History shares the same intention. Flick back to the introduction and Lewis (an assistant curator of international art at Tate Modern) acknowledges attempts to restore women’s names into the history of photography. But she asks, beyond the “genteel lady hobbyists” and the “gung-ho pioneers”, where are “the working-class women who set up studios to make ends meet” and “the ordinary folk quietly recording their communities because they knew that no one else would”?

It’s the stories of these photographers (each of whom identifies as a woman, trans or gender nonconforming) that Lewis sheds light on. The stories that didn’t make it into the traditional account of photography because they didn’t fit with the neat and tidy definition of history and progress.

Photography: A Feminist History is an account of roughly 200 years of photography told from a feminist perspective. Divided into ten chapters, it charts the landmarks in photography and women’s rights, culture and politics, as well as how they have overlapped and shaped the images photographers have taken and our interpretation of them.It would be easy for a book structured in such a way, by thematic essays and profiles, to feel choppy and rushed, but this one is nothing if not considered. From documentary photography and art as activism to the family album and social media, Lewis thoughtfully maps photographic developments and “the messy business of feminism”.

“For many of the individuals in this book, producing images was a means of understanding who they were and their place in the world”

The profiles see Lewis zoom in on 75 key practitioners. Early on we read of Bolette Berg and Marie Høeg, who ran a successful photography studio in Oslo in the early 20th century, and whose private portraits provide insight into their beliefs surrounding gender, sexuality, and conformity. Then there’s Florestine Collins, who began taking photographs in 1909 at the age of 14 to support her family and went on to open a studio from her living room (in part to avoid becoming a servant for white families and enduring long hours, poor pay and the threat of harassment).

While many chose not to emphasise their gender in their images, some forms of photography were particularly suited to tackling it, not least photomontage. Together with Lee Miller and Cindy Sherman, Hannah Höch is among the more familiar names found within the pages of the book. The Dadaists used the technique of fragmentation to critique the commodification of women’s bodies: “By depicting female bodies only in parts (a gymnast’s torso, a model’s stocking-clad legs, a mother’s arms cradling a baby) they drew attention to the multiple identities that women ‘should’ occupy as healthy, productive citizens, sex objects and nurturers.”

Arvida Bystrom

Each character study is accompanied by an image, and a highlight is Lucia Moholy’s portrait of her then-husband, Hungarian painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy. The black-and-white photograph blurs out his palm, which is raised in front of the lens, and focuses on his bespectacled, smiling face, a mix of highlights and shadows.

As Lewis writes: “It is not only an illustration of how the camera can compress depth but is also, perhaps, symbolic: his gesture dismissive, pushing her away while pulling him into focus.” The work Moholy did on the couple’s photograms and texts went unacknowledged until she revealed the true nature of their collaborative relationship in Moholy-Nagy, Marginal Notes (1972).

For many of the individuals in this book, producing images was a means of understanding who they were and their place in the world. Joan E Biren, known as JEB, taught herself photography because, as Lewis writes, she had a “visceral” need to see a reflection of her reality. The first image she ever saw of two women kissing was the one she took of herself and her lover, Sharon.“I wanted to see it,” she said.

Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus’s autobiographical series Annonciation (2009-13) sets out to counter the lack of visibility around infertility, while Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra’s frank yet tender series New Mothers (1994) shows the often-harsh realities of motherhood.

Of course, photography has its limits, and shortly after describing that subtle yet significant distinction between ‘seeing’ and ‘looking’, Lewis quotes the cultural critic and public intellectual Susan Sontag: “Life is not about significant details, illuminated in a flash, fixed forever. Photographs are.” And so, Lewis asks, how do we reconcile these limitations with the responsibilities of the photographer and the viewer towards the subject?

Like the business of feminism, the answer is sprawling and complex. But this book offers clear and cogent guidance by encouraging us to “not simply look at the photograph, or indeed its maker, but instead to try and see”.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022