What is a feminist picture? That’s the question at the centre of Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum, currently showing at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Largely featuring works gifted by collector Helen Kornblum, the exhibition brings into conversation photographs from the past 100 years, mediating on the diverse ways in which the camera has been used as a tool of resistance. From portraiture to photojournalism, social documentary to avant-garde experimentation, the collected images illuminate the intersections of feminism, civil rights, diasporic histories, indigenous sovereignty, and queer liberation.

The decision to highlight works that unsettle restrictive notions of gender and respond to asymmetrical systems of power has acquired yet more weight in recent weeks, as the overturning of Roe v Wade signals a decisive war on female and minority rights in the US. Our Selves invites viewers to consider the varied narratives, histories and perspectives that are essential to feminism today. As featured artist Carrie Mae Weems has said: “In one way or another, my work endlessly explodes the limits of tradition. I’m determined to find new models to live by. Aren’t you?”

Here are some of our highlights:

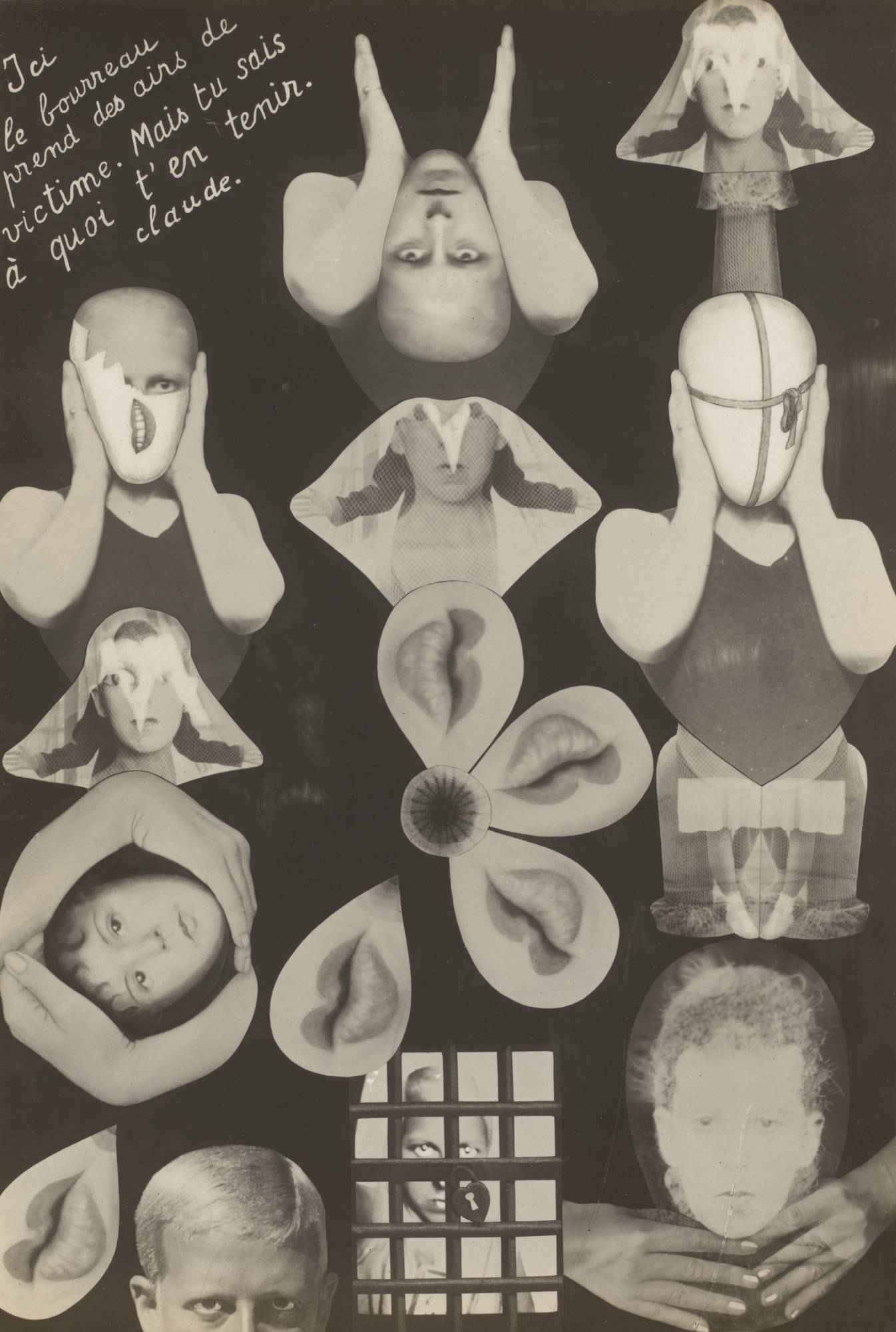

Claude Cahun, M.R.M (Sex), c.1929-30

“Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me,” wrote French surrealist artist Claude Cahun in their book Aveux non avenus (1930). The photographer, sculptor and writer, who adopted the gender-neutral name “Claude” in 1914, took self-portraits styled as various characters in an effort to challenge the strict confines of gender and sexual identity. This photomontage, published as one of the illustrations in Aveux non avenues, is an exercise in self-discovery and self-expression, and a pioneering testament to the multiplicity of personhood.

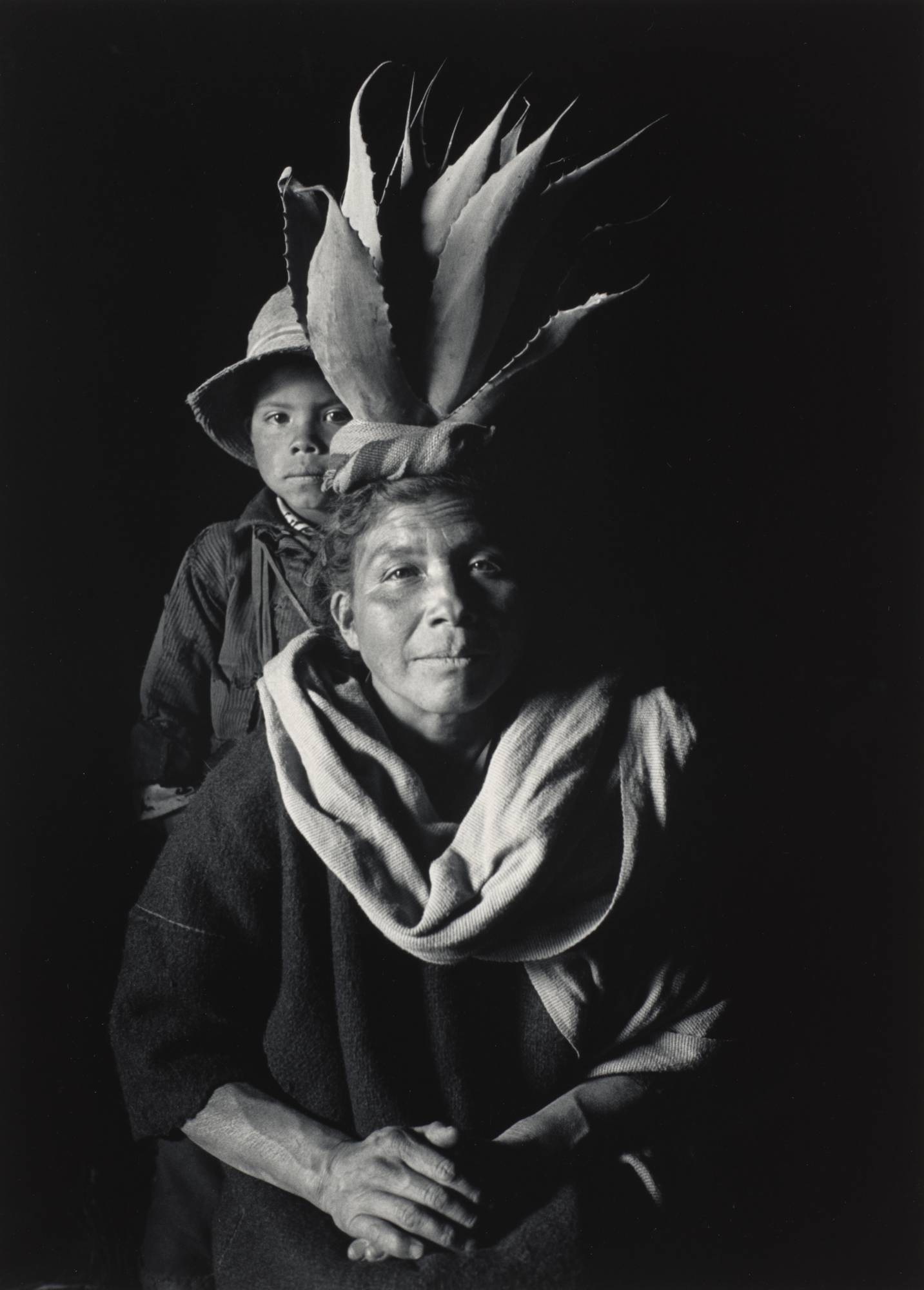

Flor Garduño, Reina (Queen), 1989

Mexican artist Flor Garduño is known for creating dreamlike black-and-white portraits infused with mysticism and inspired by her country’s surrealist heritage. In the 1980s, Garduño visited rural areas of Mexico in search of topics for bilingual literacy books on behalf of the secretary of public education. During this time, she became more familiar with indigenous communities and the experience had a profound impact on her style. This majestic portrait, captured in neighbouring Guatemala, is part of her Witnesses of Time collection and evokes her deep-held respect for the wisdom of indigenous cultures.

Susan Meiselas, A Funeral Procession in Jinotepe for Assassinated Student Leaders. Demonstrators Carry a Photograph of Arlen Siu, an FSLN Guerilla Fighter Killed in the Mountains Three Years Earlier, 1978

American documentary photographer Susan Meiselas visited Nicaragua from 1978-79 as the campaign of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) to overthrow the US-backed Somoza dictatorship reached fever pitch. While capturing this powerful protest image of members of the FSLN mourning assassinated revolutionaries, including 20-year-old martyred singer-songwriter Arlen Siu, Meiselas was presented with a bullet made in the US and asked which side she was on. “It went beyond the question of ‘Why am I taking photographs?’” she says. “It became clear to me that as an American, I had a responsibility to know what the US was doing in other countries.” The picture marks a pivotal moment in history and in Meiselas’ relation to her subjects.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup), 1990

This black-and-white image is from Carrie May Weems’ Kitchen Table Series, a performative body of work created in 1990 when the American artist was “thinking a lot about what it meant to develop your own voice”. Taken in her own kitchen using a single light source hanging above the table, Weems applies lipstick in front of a mirror while the young girl seated beside her does the same. This quiet domestic setting contains multiple mirror images, as the rituals of beauty and selfhood are enacted and reflected across generations.

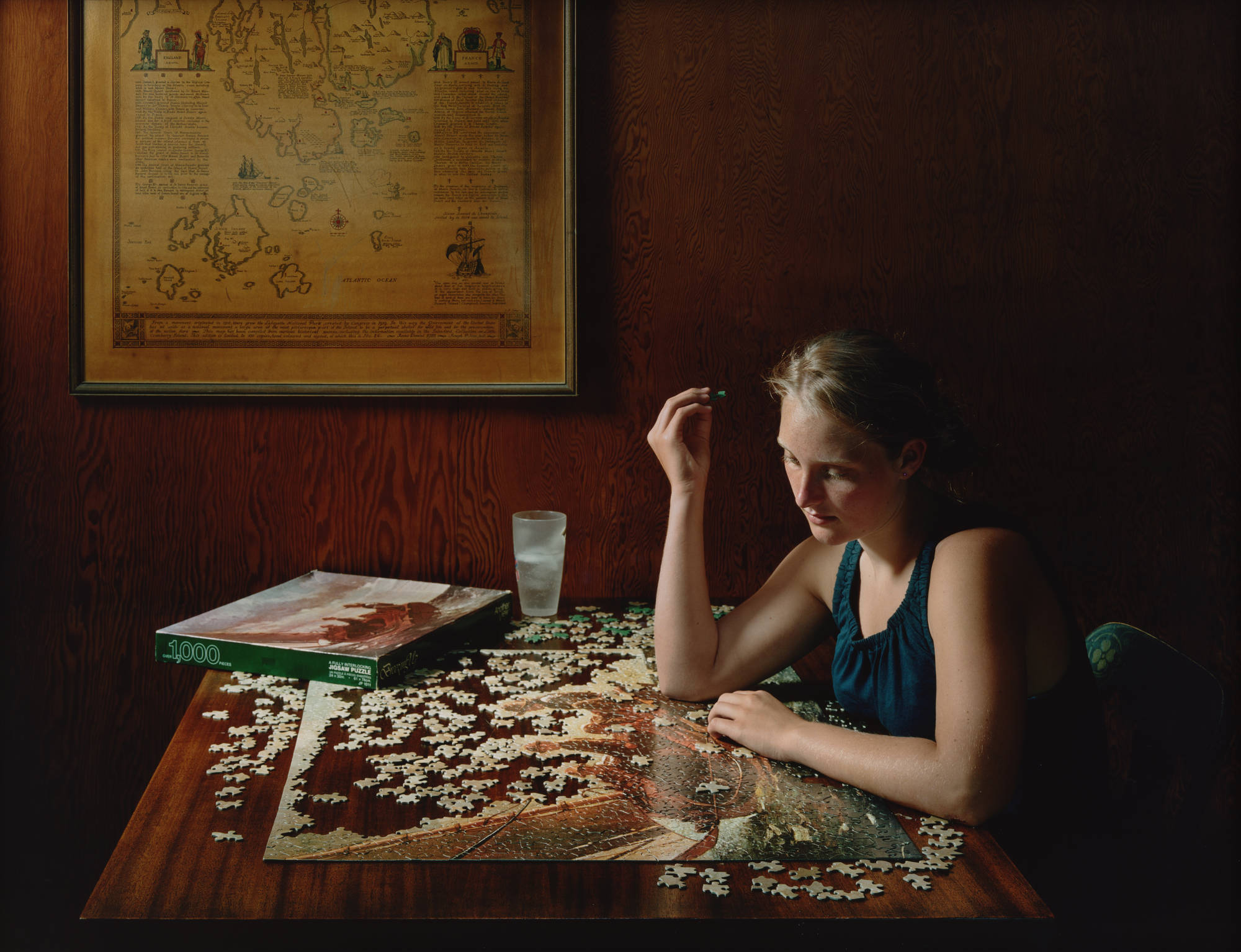

Sharon Lockhart, Untitled, 2010

Sharon Lockhart’s thought-provoking compositions are both painterly and cinematic in quality. In this untitled chromogenic print, a woman is absorbed in a puzzle. The American photographer’s use of chiaroscuro infuses the scene with a richness and grandeur reminiscent of the works of the Old Masters. There are other echoes of the Dutch Golden Age, too, in the ship painting of the puzzle and the map of the Atlantic Ocean on the wall, all hinting at colonial expansion. Though sedate at first glance, it’s as if the subject is piecing together a dark history.

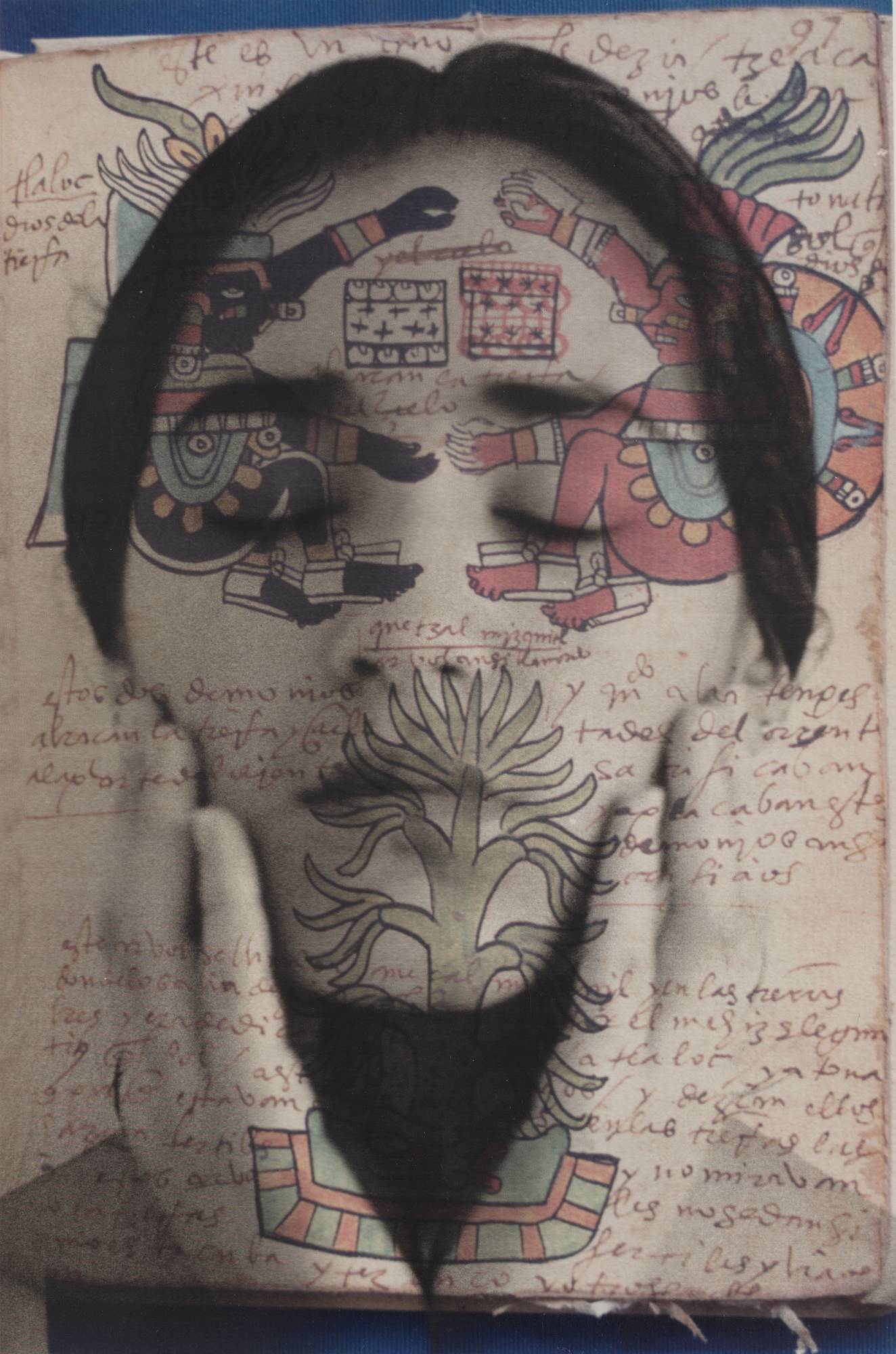

Tatiana Parcero, Interior Cartography #35, 1996

This self-portrait by visual artist and psychologist Tatiana Parcero captures a moment of calm and introspection on the journey back to oneself. Superimposed onto a photograph of Parcero pressing her hands softly to her cheeks are pictures and writings from the Codex Tudela, a cultural encyclopedia created by the Aztecs during the 16th century, in the early Spanish colonial period, to represent pre-Columbian ways of life in Mexico. “When I moved to New York from Mexico, I was feeling a little bit out of place and I wanted to recreate a sense of belonging,” Parcero reflects. “The work is a way to connect myself with my country and the ancient cultures that are before me.”

Hulleah J Tsinhnahjinnie, Vanna Brown, Azteca Style, 1990

“No longer is the camera held by an outsider looking in, the camera is held with brown hands opening familiar worlds,” says Navajo-Tuskegee artist Hulleah J Tsinhnahjinnie. This collage is part of her Native Television project, in which she creates her own vision of what she’d like to see on screen. It depicts Tsinhnahjinnie’s friend dressed in her Azteca dancing regalia, her face resplendent as she gazes upwards. The punning title references Vanna White, beauty icon and host of US game show Wheel of Fortune, as Tsinhnahjinnie seeks to reframe and recentre indigenous women in the mainstream.

Cara Romero, Wakeah, 2018

Chemehuevi photographer Cara Romero’s First American Girl series was motivated by “a lifetime of seeing Native American people represented in a dehumanised way”, and a desire for her daughter to have a different self-image. Since “all of the dolls that depict Native American girls were inaccurate” (lacking detail, lacking love) Romero imagined her own. Here artist Wakeah Jhane Myers, a descendant of the Kiowa and Comanche tribes of Oklahoma, poses in a doll box surrounded by her cultural accoutrements. The project is about “resisting these ideas of being powerless, of being gone,” says Romero. “I’m constructing a story of power and of knowledge and of presence.”

Madeleine Pollard is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs

Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum

is at MoMA, New York, until 2 October