Back in February, Elephant launched a new series celebrating the profound impact a single work of art can have on a person: This Artwork Changed My Life. Then, in September, Artsy launched its own series, The Artwork That Changed My Life, exploring deeply personal responses to individual works of art. While this overlap could have led to frustration between the publications, Elephant and Artsy have come together to present a new creative collaboration.

Both sites will share the personal stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy, jointly commissioned as part of the series. Together, we celebrate the transformative power of art. So make sure you’re following both @ElephantMag and @Artsy on social media, to keep up with each and every instalment in this exciting series.

Out today on Artsy is a piece on Caravaggio’s The Lute Player by Jacqui Palumbo.

In the opening paragraphs of Ben Lerner’s Leaving The Atocha Station, a PhD student observes in the gallery of the Prado Museum as a man stands in front of Rogier Van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross. As he watches, the man begins to weep hysterically at the foot of the Flemish masterpiece. There is a sincerity to the man’s emotion that disorients Lerner’s student protagonist. This might just be, he pronounces, a firsthand example of a “Profound Experience of Art”. My own Profound Experience is yet to arrive. It was something that I was desperate for ever since the age of fifteen, although I didn’t yet have the vocabulary for it. I willed it to happen to me, but it never did. What emerged instead was a creeping realization; a slow watershed moment that nestled itself into my subconscious. Mine was a slow awakening, with the help of a grotesque snarl from a semi-nude gorilla.

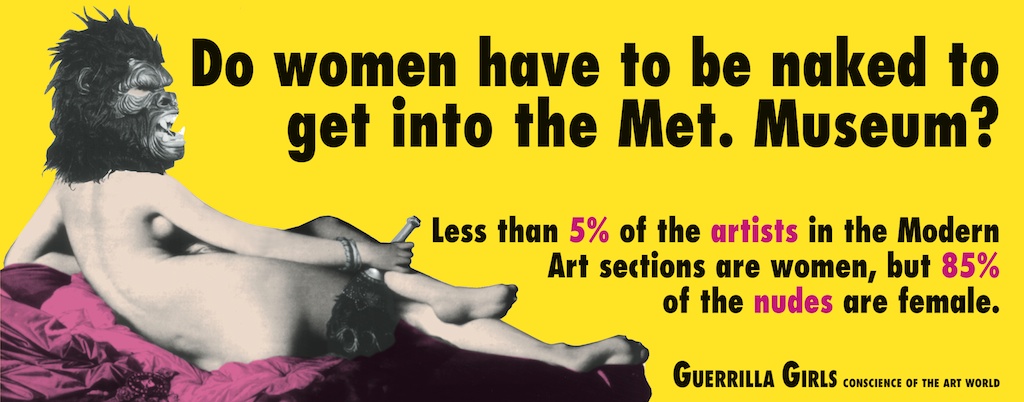

My first encounter with the Guerrilla Girls came in a GCSE classroom, when their 1989 poster, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?, was used as a hamfisted example of pop advertising and collage. Printed in A2, it depicts in primary yellow and hot pink an adapted version of La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The painting, housed in the Louvre, Paris, is a titanic example of the problematic shift of Romanticism towards the “exotic”. At its centre is the nude Odalisque, her elegant back turned away even as she glances back at her audience, a knowing smile delicately etched on her face.

This is a piece that defines art history’s approach to women; Odalisque is cast as a paradigm of the artist muse, whereby her urgent sexuality both frightens and welcomes the male gaze. Perhaps most striking in the image is not the “beauty” of the Grande Odalisque but the anatomically inaccurate proportions of her body. That long back of hers, so beloved by Victorian viewers, is painfully (even impossibly) twisted to best reveal her breasts to a beckoning and baying crowd. She is idealized precisely because she is not real: for her to be real would be to break the spell of fantasy.

“Mine was a slow awakening, with the help of a grotesque snarl from a semi-nude gorilla”

By the early days of the 2010s, when the Internet had already taken hold, nudity was not shocking. My Catholic school’s biology classrooms had long become trading centres for graphic pornography, shared via bluetooth and passed from table to table. Boys would snicker as they showed it to the girls unlucky enough to be in their perimeter. Within the four walls of this educational upbringing, semi-nude bodies were either found mangled on a cross, in paintings designed to shake the sin out of you, or on the pixelated screens of a Sony Ericsson W810i.

As such, it was not the naked body of Odalisque in the Guerrilla Girl’s reimagining that made me sit up and take note, but rather the slapstick interventions made upon her image. The poster, first commissioned by the New York Public Art Fund for a billboard, features Odalisque with the head of a gorilla. Her teeth are bared, and she is fizzing with primal aggression. Other changes have been made, too. In this work, Odalisque is accompanied by the facts: “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female” a bold font blares on the poster. It is institutional critique in its rawest and most audacious form, going right to the very top of the art world with a provocative anger that seeps under the skin.

I grew up north of the M25, and the semi-industrial, semi-rural background of Leeds felt a million miles from London—and a lifetime away from the galleries of New York. My idols included John Berger and Tracey Emin (who I crudely printed out a photograph of), placed on a pedestal alongside the most glittering, seductive institution of all: the MoMA. It was the art world made flesh; crucially, the MoMA was absolutely perfect. The wrongs of art history had no ties to this modern and cultured world that I so craved to belong to. That it could be mired with misogyny, racism, ableism and blood money had never even crossed my mind.

I didn’t cry in front of the image like Lerner’s fictional man at the Prado, but the visual impact of the Guerrilla Girls sunk deep. When I next walked around Leeds Art Gallery I noticed few women on those walls, let alone their names spelled out in cursive gold underneath. How culpable was the institution; who was the villain behind the curtain here? I had many questions, but few answers.

I later learned that the poster, intended for New York City billboards, had been rejected on the grounds that it was not clear enough. In Whitney Chadwick’s Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls, the group recount: “We then rented advertising space on NYC buses and ran it ourselves, until the bus company cancelled our lease, saying that the image was too suggestive and that the figure appeared to have more than a fan in her hand.” It’s true; the Odalisque of the Guerrilla Girls appears to be holding not a fan but a limp cock.

“When I next walked around Leeds Art Gallery I noticed few women on those walls, let alone their names spelled out in cursive gold underneath”

The gateway drug of the Guerrilla Girls, with their anonymous army of angry women in masks, paved the way for a new kind of art-historical knowledge. From the Guerrilla Girls begins a lineage consisting of the likes of Nan Goldin, with her recent P.A.I.N protests against Sackler-funded institutions, right through to Lorraine O’Grady’s Olympia’s Maid (1992); the V-Girls’ satirical art panel discussions (1986–96) to Hans Haacke’s MoMA Poll (1970). It also meant that my experience within the art world, from completing a university course primarily attended by the white and privately educated to the institutional expectation that unpaid internships are the norm, all became intertwined with a realization that the art world is an inherently evil place. This knowledge was as freeing as it was damning.

In Hito Steyerl’s Duty Free Art, she writes “contemporary art is made possible by neoliberal capital plus the Internet, biennales, art fairs and growing income inequality… let’s add real estate speculation, tax evasion, money laundering and deregulated financial markets to this list.” Reading this in 2018, it carried forward my education in institutional critique, but this was a painful lesson that had started some eight years earlier with the A2 poster of the gorilla-faced Odalisque.

Against the backdrop of years of austerity, which has only strengthened class divides and turned art into a cultural battleground, the anger that permeates the work of the Guerrilla Girls still feels fresh. It is a rage that will propel the next generation of art activists, despite the tendency of the art world to co-opt the very critiques levelled against it and absorb them into the institution. This realization that the art world exists as a morally flawed marketplace is a bitter pill to swallow; I only wish more people would take it.

Image: © Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

Did an Artwork Change Your Life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life”.

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Caravaggio’s The Lute Player by Jacqui Palumbo

READ NOW