Many years ago, I visited the Guggenheim Museum, specifically on a mission to see the Deanna Lawson exhibition held in honour of her winning the Hugo Boss Prize. Her exhibition was featured in the gallery at the top of the museum, and my personal preference is to take the elevator up and circle on down, staying as close as possible to the artwork on the outer wall (because of my fear of heights.) When you are close to the wall, you see the best part of the Frank Lloyd Wright space: the galleries tucked into the sides of the spiral, pulling you in and out of the soft current that is the rotunda. It is also, in my opinion, here that they take their risks, allowing their most intriguing exhibitions to be on view there. This is where I came across Ashley James’ first exhibition, Off the Record, featuring works pulled from the Guggenheim’s collection.

“Black study is just so much about the way that one views the world that an engagement with it means reconsidering and centring the question of power. I think that question governs anything that anybody writes or does for any project. But perhaps for me, it means that I’m explicitly interested in power and artists that are thinking about it.”

Off the Record utilised artwork to question historical records–whether those records came from newspapers, government files, or the museum’s archives itself. It posed questions such as: Who got to create history? Who was remembered? Who was chosen to document it? And displayed artists inspired to take it upon themselves, as they often do, to tell the world a different story than what was traditionally accepted. I was astounded by the premise–personally coming out of 2020 disoriented and quite disillusioned by museums and their exhaustive statements. Especially a museum such as the Guggenheim, as I had watched closely as their Basquiat exhibition accented the racial cracks hiding in that beautiful building’s foundation. It was obvious that James had an acute intuition for conversations that needed to be happening on an institutional level–and nothing was going to stop her from adopting that artist mentality to tell it… even if that meant telling on the museum, too.

As someone who did not grow up going to museums or looking at art–but now works in art and spends every spare moment exploring it–I tend to adore those in the art world who share a somewhat similar background. It is one thing to be pulled into a gallery and have someone dazzle you with their knowledge, pointing to significant objects and cluing you into the artist’s hidden techniques. Not that that isn’t important! –but it is quite another to walk into these spaces that cater particularly to those educated to the “in the know” and “of the scene”, and find a place for yourself.

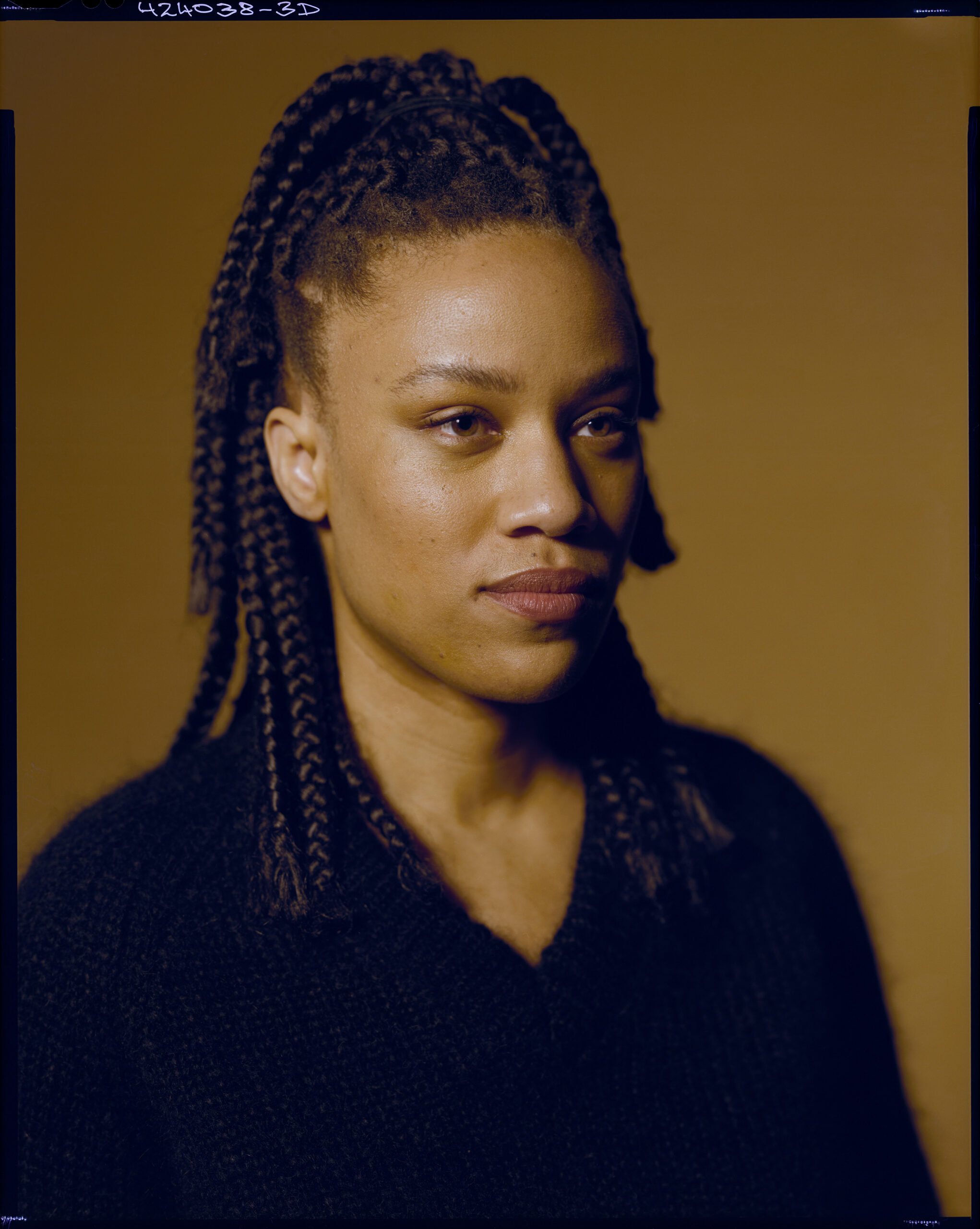

James had no idea that curation was in her future, yet a variety of life events led her there. “I was always interested in art-related things, and a series of opportunity-meets-preparation moments led me to curatorial,” shared James. “I came from a family of working-class Jamaican immigrants. So, the idea of curatorial was not something that was anywhere in my purview. In fact, even though I knew that art history was a discipline, I didn’t understand it as something.” Rather, James decided to pursue an education centred on English literature and African-American studies. “I feel like literature itself was a path that already felt on the outer edges of what was permissible for an immigrant family that wanted, of course, the engineer and doctor.”

While getting her PhD, James was influenced by her fellow students who were writing on art. “For whatever reason, I think it was just kind of like a confluence. It was a reflection of the moment… when I was writing my dissertation, I knew that I had wanted to write about visual artists too.” James also had the opportunity to curate her own exhibition at Yale, which provided the training that she needed to understand the role of a curator. “I loved every aspect of it. I loved choosing the works. I loved the exhibition layout process. I loved writing the text.” Then, an opportunity to pursue a fellowship at MoMA, where she worked on retrospectives for Adrian Piper and Charles White, really put the pieces together. “After that fellowship, it was kind of just like, I’m not going to go back to New Haven.”

“Taking on the rotunda is such a statement. There’s a necessity of bringing in folks that have not had that kind of monumental gesture afforded to them.”

That’s what makes a strong curator, or an interesting one at least. Someone who is able to utilise a winding path, a culmination of various studies, and a somewhat outsider mentality to develop exhibitions that ask compelling questions. James’ newest exhibition, Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility, features almost 30 artists whose works utilise the concealing of the body to analyse the complications of visuality. At its essence, the exhibition explores the longings that Black people have always been at odds with the desire to be seen and the desire to be hidden from sight (though James emphasises that the dualities of being seen are often at the heart of the human condition.) And more, why society and white people are constantly unable to decipher between the context of the two. You can see James’ past studies on racial formation and representation on full display here. “Black study is just so much about the way that one views the world that an engagement with it means reconsidering and centring the question of power. I think that question governs anything that anybody writes or does for any project. But perhaps for me, it means that I’m explicitly interested in power and artists that are thinking about it.”

I asked James point blank if she felt any pressure to create exhibitions that centred on the Black experience–given her role as the Guggenheim’s first full-time Black curator. She distinctly said she did not. “I can truly say that, for various reasons, I’ve never felt censored or steered or encouraged to do something that I didn’t want to do. Like, I really can feel proud of what I put my name on.” She does not feel pigeonholed. Her work comes from a place of passion and intuition. “I wouldn’t say that I’ve self-consciously said, I’m going in, and I’m doing shows that are connected to this. But whether it finds its way into the work by way of the artists that I gravitate towards… I’m just more likely to pursue something like that as opposed to something that wouldn’t consider power.”

I’ve been seeing article after article on Going Dark praising the exhibition for its focus on “the rare.” The rareness of Black artists at the museum. The rareness of groups shows in the rotunda space. The continued rareness of Black curators at this institutional level. So why are exhibitions like hers so rare? “The hope is that there’d be many more, not only Black curators but curators of colour who are entering the space with new perspectives.” She also noted that this is something the museum is interested in addressing. “Taking on the rotunda is such a statement. There’s a necessity of bringing in folks that have not had that kind of monumental gesture afforded to them.”

It’s very clear that James envisions a future for museums that really brings the outside in–something that museums often say they want but have a hard time putting into practice. “I do believe in the museum as this kind of civic space that is one of the last standing spaces that has the potential for transformative change for the individual. And that it doesn’t just happen one way. It’s not just that we offer this change but that it is, in turn, what allows a museum to grow. It’s a dialectic,” says James.

In the meantime, James is busy keeping her eye on the prize and focusing on the work. “You can never fully determine how anything will be received by the world. That is why I’m obsessed with the legacy of the 60s, which tells us that no work of art is complete until a visitor sees it. And in some ways, I feel that about any creative thing that gets put out into the world. You can’t control how somebody is going to interpret something–you can only be true to your intent and do your best to express it.”

Written by Shaquille Heath

Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility is on view now at the Guggenheim Museum.