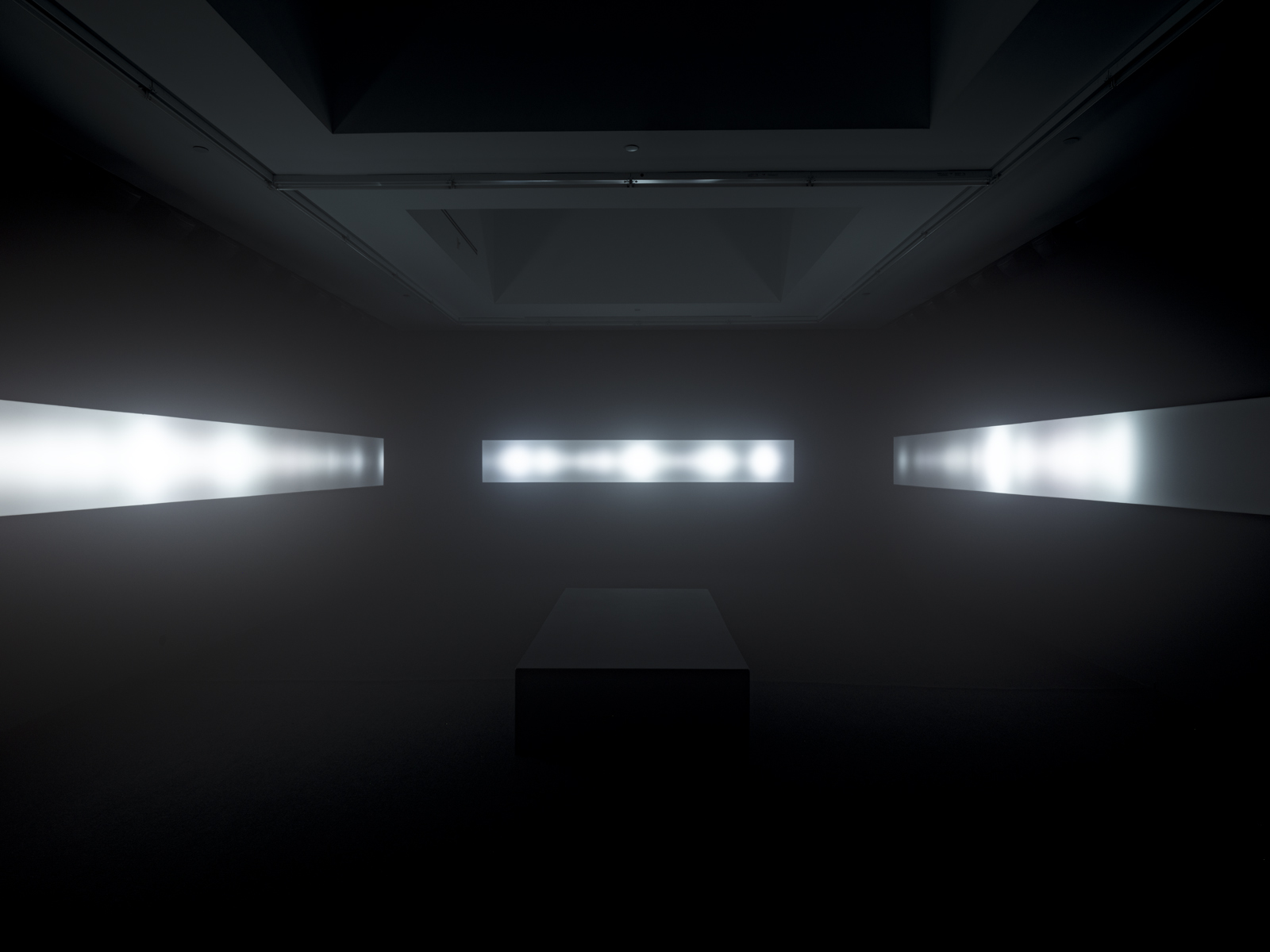

It felt like what one would hope dying would feel like: misty rhythms that twisted and untangled themselves around flashing lights and the smell of earth, industrial symphonies and primordial humming, and at the root of it all, some kind of voices, or really, some kind of voice. This was the experience of walking into the immersive room installation at musician and interdisciplinary artist Jónsi’s most recent exhibition, Vox, at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Los Angeles.

As the lead singer of the now legendary Icelandic post-rock band Sigur Rós, Jónsi’s artistic aptitude and whimsical falsetto have helped craft a discography that displays an impressive breadth of style. The group’s music ranges from epic, soundtrack-esque compositions and emotionally evocative abstract soundscapes to more traditionally structured songcraft like their most streamed track on Spotify, Hoppípolla. Such a breadth of experimentation is indicative of a desire for exploration and visceral expression that has propelled Jónsi out of the traditional music industry and into conceptual, fine art spaces that most musicians don’t often find themselves.

Jónsi has been showing sensorial installation work with Tanya Bonakdar since 2019. An artistic multi-hyphenate, the human sensorium is, in many ways, Jónsi’s ultimate canvas. His exhibitions utilise nearly every aspect of human experiential capability: scent, touch, sound, and sight. They are immersive, conceptual experiences that are highly cerebral with no clearly defined thesis. Meant to be meditations on an object of interrogation or attempts at conjuring some ephemeral kernel of experience, they are also almost always related in some way to the natural environment. His second to last exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar, titled Obsidian, was a meditation on the eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano in Iceland. Paired with the release of an album with the same name, Obsidian used sound, scents, sculpture, and an entire room installation to evoke and interrogate the volcano’s eruption.

The urge to move beyond the limitations of language into sublimity shows itself in much of Jónsi’s work. He has had a historically complex relationship to linguistics, notoriously often singing in what Sigur Rós coined “Vonlenska,” or in English, “Hopelandish,” a style of non-linguistic vocalisations distinct to the singer. Vox was specifically created as a meditation on the human voice, which, as cited by the artist, sits at mid range frequencies adjacent to the official frequency of the Universe, 432hz. There is something mystically evocative about his artistic ethos: it seems aimed at the disintegration of thought into an embodied experience.

On a grey Los Angeles morning, Jónsi hopped on a call to discuss his entry into the art world and the intricacies of his practice.

I had honestly been relatively unfamiliar with your fine art work until your most recent exhibition, and when I went I was utterly blown away. It’s funny because I originally come from a music background, so I was loosely familiar with Sigur Rós but had no idea you were in the art-world in this capacity. How did you transition from the record industry to the fine art world? I’m curious what impulse that bridge was initially built upon.

I guess it was a little bit of a natural progression. When you grow up in Iceland everyone is a musician or an artist or something. So I was surrounded by artists growing up. I had a lot of friends doing art related stuff, so I’ve always been curious as to how I could move into that field and try something different. I’ve been doing that for a few years now. It’s stressful. It’s stressful to be an artist. (laughs.)

I’m sure. It’s a whole other process, I’d imagine. Music can be so visceral and in the moment, and I’m sure there are parts of your practice that are like that, but I’d imagine in the art-world everything has to be more conceptual in a way?

Exactly. Everything has to be so conceptualised. This is cool for me because I come from a non-conceptualized musical background. In the band Sigur Rós, for example, the less we talk, the better, basically. Growing up, you’re always surrounded by that myth that the less you talk about things, the more things just flow. They are how they are: magical without being too analysed. This world is the exact opposite. Everything is very conceptualised: talked about and analysed to death. It’s interesting to me, and I kind of enjoy it now. I like it when you have something in front of you, and you see a connection or try to figure out the connection between things. It’s an interesting experiment.

That makes a lot of sense. That ties into something I’ve been thinking about regarding your practice in general, including your work in Sigur Rós, which is your relationship to language. Your compositions and your records have a sublime weight to them. They’re very immersive. So, it makes sense that you’d go into the art world and create these very immersive experiences. I know Vox, for example, was a meditation on the voice, and you’ve talked about how the mid-range of frequencies, where the voice lies, is this kind of universal thing. So my question, contextualised by this background, is, how do you think about the voice? Especially as a singer and somebody who doesn’t necessarily vocalise in linguistics.

Yeah, I mean, starting off as a singer in a band when I was eighteen. I just started singing because nobody else was singing. I’ve been basically singing all my life. It’s interesting, it’s just like a muscle you train. From the beginning I never liked putting words to my singing voice. It always feels like you’re trying to put something in that doesn’t fit. So, in the band, we’ve always been empty of language, in a way. So when doing this, everything is kind of nonsensical— pure sound. There’s no meaning to anything, but maybe it is really meaningful. Maybe for us and our society, there’s no meaning. Sometimes, it feels like when you’re singing in non-language, it pierces deeper, or maybe it pierces less; it’s really hard to know.

It’s more visceral at times.

Maybe people make up their own language and meaning. It’s cool.

It feels like the human sensorium is your true canvas. I know in your exhibitions you’re interested in vocals and sound, but also scent and touch. I’m curious where— and it’s ok if it just came out of thin air— that interest started. You make your own scents for your exhibitions, right?

Yeah, I have a small perfumery. I’ve been doing it for about fifteen years or something. I’m just obsessed with scents. Probably everybody loves scent in some kind of form: food, perfumes, or something. I started doing it because I loved scents and wanted to see how it worked. I have a small lab in my basement, which has a thousand bottles of aroma molecules and stuff like that. When I was looking at the art world before I got into it, I would go to exhibitions and just see what was out there, and sometimes it just struck me as kind of dull, unmoving and uninspiring. At times, I felt it kind of inspiring, almost how uninspiring it was. (laughs.) So I just went in and started to try different things and think about how different scents would trigger stuff in people with smell, sound, and visualisation. It’s all connected somehow— sound, melodies and harmonies, scents, bass notes, mid and top notes, everything connects. It makes sense to have as many of these things triggered as possible.

Totally. It’s like a painting in a certain way. In that sense too I’m curious how you pick what scents go along with your audio installations. Is it just what feels right in an abstract way? Or are you navigating the process conceptually?

For example, with Vox, I tried to use root material. We talked previously about how the mid-range connects to our core and how the voice is the ultimate trigger tool. It really connects to our roots; it goes so far back, probably farther back than language singing-wise. My theory is that people probably started making sounds and singing before they started talking— it seems more natural somehow. So, I wanted to use root materials. For Vox, the main scent is vetiver and vetiver root, which is a kind of grass. It’s one of my favourite scents in the world. My ultimate goal is to make a perfect vetiver scent.

Wow. That is so cool— you’re kind of crafting a pallet. I think a lot of people in music could relate to that as a lot of musicians literally see the music they’re creating. Sound can have a relationship with colour.

Synesthesia and stuff like that, yeah.

On that note, I’m curious about how you go about creating the soundscapes for your exhibitions. Are you thinking of it as a composition, like the way you would score something? Are they improvisational?

It’s interesting. I always start with the voice for some reason— it feels like the most natural thing to start with. Then, I usually build it up in sections: four or five sections or something. Two more melodic, choir-esque sections, two more soundscapes, kind of wacky, fun compositions. So yeah, it’s a different approach. I just kind of slowly build it together, and it makes sense somehow.

This is a question about post-production. Forgive me if this is an uneducated take, but it felt like in Vox the production styling and texture was similar to Bon Iver’s work, particularly his album 22, A Million, but in a more abstract way. I’ve been trying to wrap my head around how you mix something in that way for so many speakers in a 360 format as opposed to stereo. Could you delve into that whole process?

Yeah, Vox was all about basically vocal experiments. So I was using Harmony Engine, a vocal plugin that Bon Iver and a lot of pop guys use. Playing around with that stuff, also using an a.i. synth to put my voice into. Just a lot of vocal experiments, seeing what comes out of that. Mixing wise, it’s really fun when you’re in a space where you don’t have to think in stereo. Here, you can have more speakers. It’s extremely satisfying to mix the sounds in 360. It offers a lot more of a fun element.

Amazing. And mixing is kind of its own form of songwriting as well.

Yeah, exactly. I had my friend, who’s a mixing engineer, come in and help me finish off the sound and stuff. When you come into the room, you also have to mix and tune the room itself and deal with sound reflections. When I did an exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery four years ago, I had speakers hidden in the walls, and I didn’t think about putting carpet on the floor. There were these giant concrete slab walls and floors, these extremely hard surfaces, and so you got these insane reflections on the walls— it was really echoey. I didn’t even think about that. So I kind of have been learning as I go.

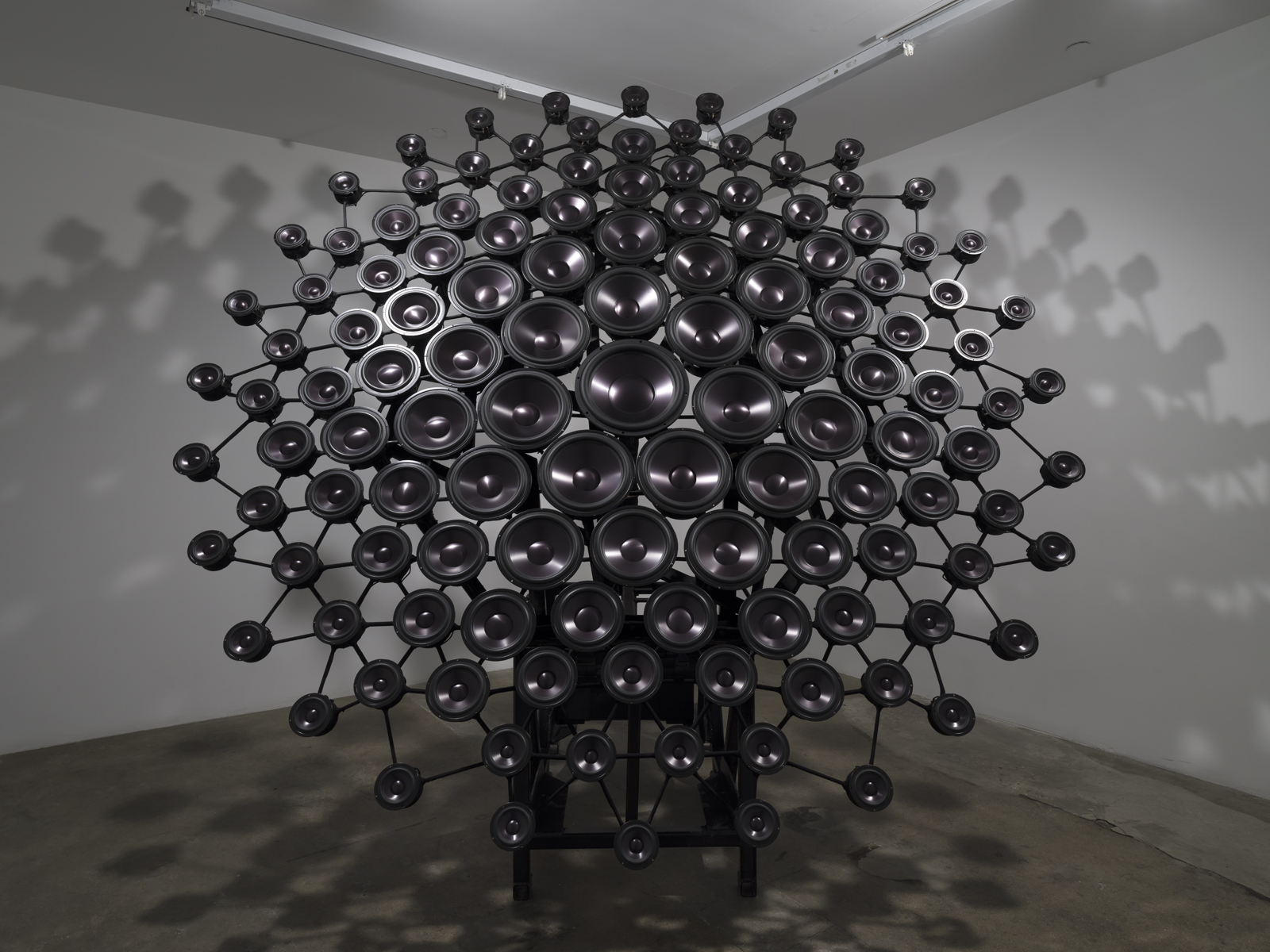

There’s a kind of physicality to sound that you play within a sense, you craft sound sculptures. But I know you also make literal sculptures as well. Could you talk about how your physical sculpture work fits into your other sensorial work?

It’s just another sense, I guess. When I entered the art world, I really wanted to do something physical with my work. When you work with sound all of your life, you’re working with a kind of invisible medium. There’s nothing there— it’s just in the air. So I really wanted to do something physical, just make something with my hands. Growing up, I worked in a steel factory. My father did all this metal work, so it was satisfying to do stuff with my hands. It’s nice to mix all of this stuff together: sculpture, sound, and scent.

I’ve noticed that most of your work deals in some way with nature, which is obviously a broad term at this point. People talk about nature all the time. But I know Obsidian for example had to do with a volcano. And even with Vox, the voice is in relation to a conception of the universe which is more mystical and more in relationship to itself.

(Laughs.) I like that.

(Laughs.) I’m happy you do. I’m curious what you think about that. Is this an unconscious tendency or a more intentional relationship that you have to “nature” as an idea?

Good question, actually; I kind of don’t know. It’s not really intentional, it just kind of happens like that. Nature is just a really broad term. I feel like everyone’s doing “nature” art now with climate change, and it can be cheesy. But I guess I’m there, too (laughs.)

But I think you do it in a very authentic way. Your work doesn’t feel like it’s commercialising the concept at all.

It’s interesting times we’re living in now, where climate change is real and happening in front of our eyes, and we’re just scrolling in this doom world watching disaster after disaster. And it feels like no government is doing anything.

Totally. And you mentioned scrolling. That makes me think of the voice in the time of social media: as we scroll we’re bombarded with voices but it doesn’t feel like you’re speaking to anybody.

I know. It’s basically like speaking into the void.

That’s what I loved about your work. It felt so visceral to me at a time where things are so mediated. Thank you for that.

Written by Theo Meranze