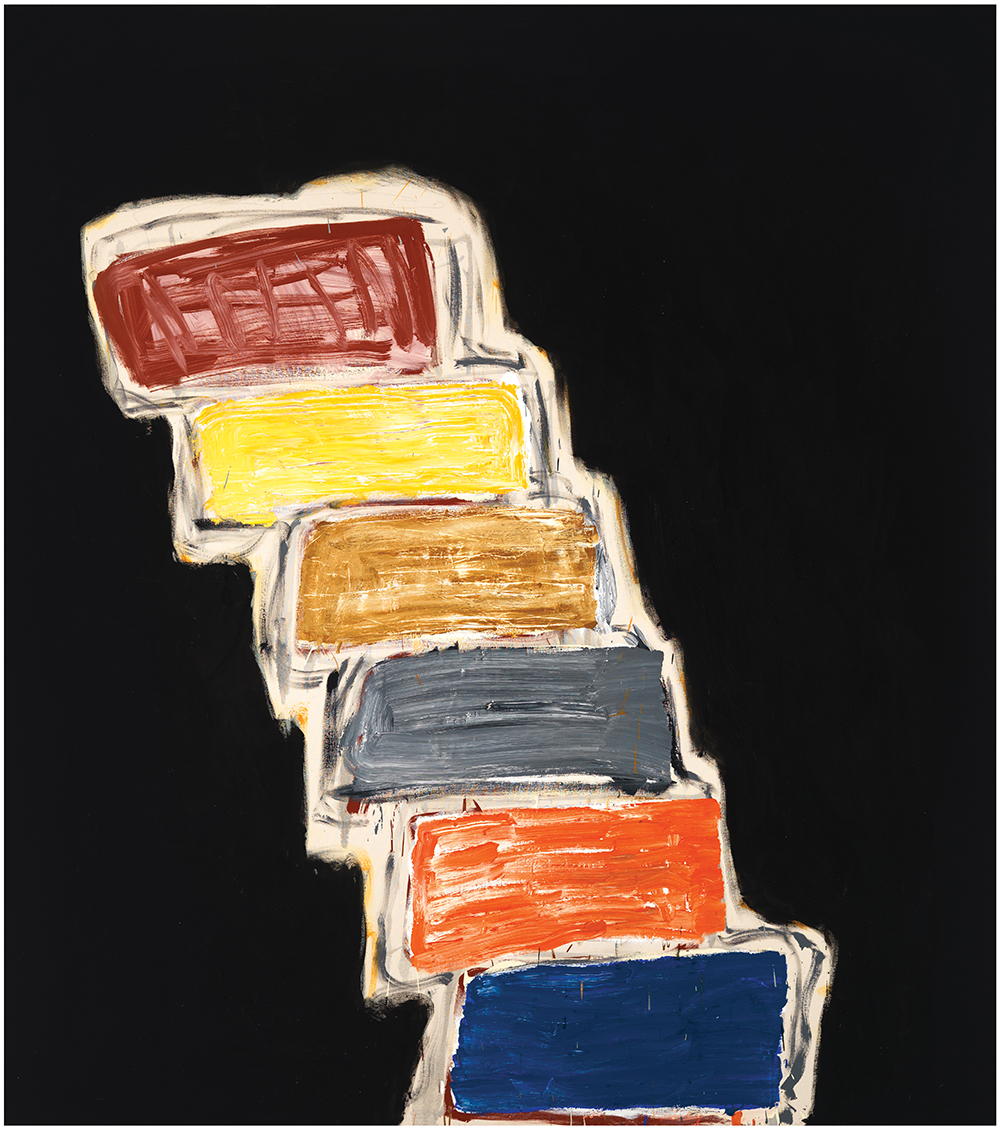

Gillian Ayres The Dew Larks Sing 2014 Oil on canvas (diptych) 99.5 x 140cm

A deep seriousness about the value and fragility of life and art connects the British artists GILLIAN AYRES, JEFFERY CAMP, BASIL BEATTIE and JOHN MCLEAN, part of a generation of painters that grew up during or just after World War II. Through the art world’s other distractions and flirtations, they have all held onto a passion and belief in the romantic, philosophical and physical language of paint. Might they be art’s last true bohemians? asks SUE HUBBARD.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 26.

These days the term ‘bohemian’ is a bit of a cliché in artistic circles. It probably emerged in France in the nineteenth century when artists and writers congregated in low-rent Romani neighbourhoods. Those with ‘proper’ jobs saw them as anti- establishment and inclined to free love. They stayed up too late, drank too much and rubbed shoulders with the marginalized. In 1894, George du Maurier’s best-selling novel Trilby, about the fortunes of three expatriate English artists, their Irish model and two colourful central European musicians, who go off to live in the artists’ quarter of Paris, helped to romanticize Bohemian culture in the uk.

But society and the art world have changed. Artists may still be hard-drinking and fun-loving but, with the enormous prices achieved in auction rooms and by multinational blue-chip galleries, the vision of the artist starving in a garret for the sake of his or her art seems quaintly outdated. They are now as likely to be appearing on tv shows as surviving on absinthe and a tin of sardines.

An earlier generation of British artists, still at work today and for whom painting has been their life’s passion, started their careers in a world where there were very few galleries or collectors and hardly any art magazines, let alone an international jet-setting glitterati quaffing champagne at private views from SoHo to Shoreditch, platinum credit cards at the ready.

These are artists whose whole lives have been dedicated to an exploration of their chosen medium, to the search for authenticity, originality and imaginative truth. Artists who, against the prevailing trends of video, installation and increasingly assistant-produced art, have continued daily to get down and dirty in their studios in the ongoing belief that painting still has a voice through which to express our deepest human concerns amid the prevailing postmodern clamour.

GILLIAN AYRES

Just before D-Day, when Gillian Ayres was 14, the brother of a friend who’d been serving in the army arrived ‘out of the desert’ and took them both for a treat to a Knightsbridge hotel. Previously Head Boy at Winchester, he soon, as Ayres puts it, ‘got bumped off’. She remembers thinking, then, in the midst of war, that art was all that human beings leave behind. It is something she still basically believes. In 1946, alarmed by Ayres’s determination to go to art school, her headmistress warned her mother about the sort of men her daughter would meet there. Too young at 16 for the Slade, Ayres gained a place at Camberwell—though her nice parents would have preferred her to marry a nice doctor. She had no grant and though she received 30 shillings a week from her family her need of money to fund her voracious smoking habit led her to model (nude) for the Camera Club. She never told her parents. She was, she admits, pretty bloody-minded when young.

At Camberwell she rejected the prevailing Euston Road ‘measuring thing’ approach and found her tutor, William Coldstream, dictatorial—‘it was dot and dash and measure.’ So she began to attend Victor Pasmore’s Saturday morning classes, where he talked of ‘feelings’ and embraced abstraction. In 1950, two months before her final examination, she walked out of Camberwell—‘What should one have taken it for and for whom?’—and caught a train to Penzance and spent the summer working as a chambermaid. Back in London she turned down an allowance from her father to go to Paris and did a series of uninspiring jobs. An opportunity to work at the aia gallery gave her the chance to meet some of the most original artists of her day and it was here that she began to find her own creative vision.

It’s hard, now, to understand just how hostile the general public was to abstract art at the time. As Herbert Read wrote, it ‘met with almost universal resistance in England’. But the revelation of Abstract Expressionism in the 1956 Tate exhibition Modern Art in the United States was a creative watershed. Ayres was elated by the energy of the Pollocks, de Koonings and Klines and determined that from then on she’d leave the traces of her painterly actions on the canvas and allow the paint to speak for itself.

Now into her 80s, she lives in a remote cottage in Cornwall with her ex-husband Henry Mundy and their son Sam—both painters—and numerous cats and dogs. Although no longer in the best of health, she paints most of her waking hours. Her recent show at Alan Cristea was a triumph of originality and invention. She recently told me: ‘I love obscurity in modern art. I don’t want a story. There are no rules about anything. I just go on doing what I do. I want to do nothing else.’

Arguably her ‘formalist’ works appear to deny any direct reference to the external world. Yet these life-affirming paintings continue to push against their own limits to speak, not only of a passion for paint, but of the light, lyricism and sensuality of the natural world. ‘The act of painting,’ Ayres says with total conviction, ‘is an act of belief.’

JEFFERY CAMP

When I arrive at Jeffery Camp’s home in Stockwell in London the walls are crowded with paintings. They are mostly by him but I spot a lovely little Euan Uglow lurking in their midst. His house may be an ordinary domestic terrace on the outside but inside it’s a haven for the making of art. He paints in what for most people would be the front bedroom, which also serves as a sitting room.There’s a huge-flat screenTV hunkered apologetically in the corner amid the brushes, rags, tubes of paint, old and new paintings and offcuts of wood that he uses to make his irregular-shaped paintings. There are also a couple of easels and some Arts & Crafts stools he tells me were made by his father. Now in his 90s, he’s wearing his familiar beret as he settles himself in a chair amid this organized chaos like an inscrutable, white-bearded sage. His wit is dry, his speech disconcertingly slow, as though he’s deliberately making you wait for an answer. Just as when I first met him over 20 years ago there’s a sense of mischief about him, as though he’s enjoying the role of gnomic artist, leaving you tilting slightly vertiginously off the end of your question.

Camp grew up in Lowestoft where Benjamin Britten’s father was his mother’s dentist. At the art school next to the library, where he remembers reading the Kinsey report and books on El Greco and Rembrandt, Miss Varley showed him the ten stages of painting a Russell Flint. She taught him, he says, everything, including book-binding, painting the figure and perspective.

Full of joyful, careless gusto, his work is impossible to categorize. It’s as if Edward Ardizzone had interbred with William Blake, with a few genes from Franz Kline thrown in for good measure. There’s a complex yet intuitive geometry to his paintings, with their dissolving figurative elements of people and coastal views. Colour is dabbed on with a series of small brushes, then pushed and teased across the surface. He has a huge knowledge of materials and has written several ‘how-to books’ on painting. Often, he tells me, he just destroys the image he’s working on, laying it on the floor, then erasing it with turps. Washing it away allows for a greater freedom to move it around. He’s been known to set off in the morning with a dozen or so odd-shaped bits of wood in a Sainsbury’s carrier bag to go and paint. His light is luminous and there’s a seamless symbiosis of figure and landscape that few other artists have been able to achieve. Whimsical, playful, yet formally serious, these are paintings that exude soul. Rainbows, lovers, seascapes: Jeffery Camp’s lyrical, dissolving, jewel-like works capture an English sensibility with the palette of Bonnard.

BASIL BEATTIE

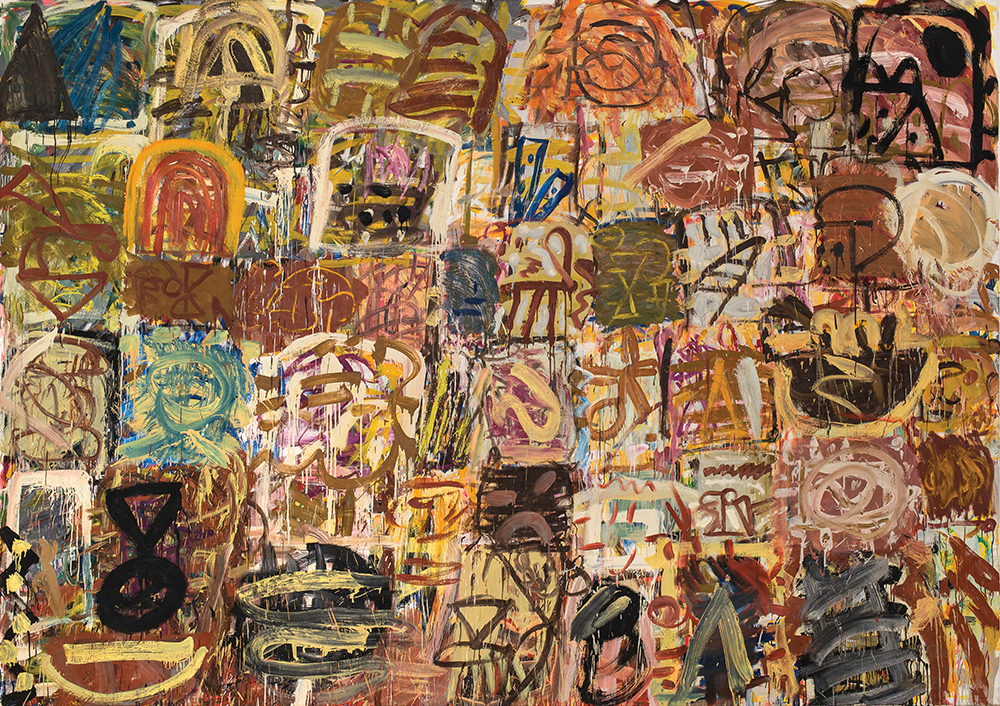

Basil Beattie’s paintings are not easy. Physical, demanding, raw and, at times, disquieting, they confront the viewer with a series of ziggurats, tunnels and staircases that apparently lead nowhere, painted with a deceptive ease and openness.The nervy edginess, the existential angst has always made him a ‘difficult’ artist, which, despite his being a tutor at Goldsmiths, means he has never quite fitted into the slick commercialism of the London art world. He might have been happier living in Germany where his work would have sat more comfortably with that of Kiefer and Baselitz than with British artists of his generation. His iconography, though essentially abstract, has its roots in the perceived world. His hieroglyphic images suggest a subterranean vocabulary con- cerned with the struggle of human existence. His horizons, like death, beckon and, Beckett-like, we have no choice but to go inexorably on towards them.

There was little incentive in Basil Beattie’s early life to become a painter. West Hartlepool where he grew up was a shipbuilding town, his father a signalman on the railways. There were no books at home, though his mother did visit London once. Going to the local secondary modern, he didn’t know anyone who’d gone to the local art school, the building next to the bus station that fascinated him on his trips to the Odeon cinema on Saturday mornings. There, from the age of 15, he was to study everything from architecture to street design.

A place at the Royal Academy could only be taken up after the requisite two years of national service. It was ten years after the war and Beattie was stationed in Cologne, still mutilated by bombing. It was there, in the museum, that he first encountered Picasso’s Guernica. Prior to that his influences had been Walter Sickert and his heirs Ruskin Spear and Carel Weight. At the time Beattie says he knew nothing about American paintings: ‘There weren’t any publications and what I wanted to express was not clear. I felt very much on my own.’

Beattie was part of the first generation of working-class students. ‘We tended to stick together. You could tell who we were. We were the only ones in jeans.’ The 1961 Rothko exhibition at the Whitechapel curated by Bryan Robertson was seminal. ‘I realized that Rothkos were not just arrangements of colour.That they had another dimension and were not simply formal aesthetic judgements.There was something existential about them, something very different to the St Ives paintings I was used to seeing.’ He tells me that he always knew he would never sell much. ‘Now, at least I sell. The thing is,’ he says, ‘that when I set off on the business of making a painting I don’t know how it is going to be. Meaning comes from the process of making. You have to be prepared to respond to ideas that you didn’t have at the beginning of the journey, to learn from what you do.’

JOHN MCLEAN

The son of John Talbert McLean, a commercial artist and art teacher, John McLean was born in Liverpool but grew up in Scotland, largely in the Arbroath, famous for its smokies. At the age of 12 he learnt that he could impress by painting and earned his first commission. At 15 he travelled to Dundee to join the Communist Party and, as a teenager, developed a line in gritty Social Realism, painting Arbroath harbour with its fishwives. But it was a chance encounter with a catalogue in the autumn of 1960 from the Situation exhibition, which featured 20 abstract artists including Gillian Ayres, John Hoyland and the Dundee-raised William Turnbull, which ‘opened up the future’.

Life for McLean in London in the ’60s consisted of two attic rooms in Balham with a shared bathroom, living on a student grant and his wife Jan’s salary as a fledgling maths teacher. To paint, McLean had to roll back the carpet on the linoleum floor. Ironically, despite having a thorough academic education like many of his heroes, such as Braque, as a painter he is essentially self-taught.

His precision and expressiveness are reflected in his resolutely abstract paintings. He is an extraordinarily sensitive colourist and has said that ‘my pictures have no hidden meaning. To understand, all you have to do is look. Everything works only in relation to everything else…I like my pictures to be simple and direct.’ There’s a visual lyricism to his paintings, which are, as that other recently departed great colourist Bert Irvin said, ‘blessed with a Matisse-like ability to dispose colour to dramatic and meaningful effect’. Dynamic and fluid, his shapes and vibrant areas of colour seem only momentarily to be fixed in their relational positions. He seems to draw with colour, weighing the subtle relationships between edge, weight and the position of his chosen forms.

As his friend and contemporary the painter Geoff Rigden once said: ‘He’s an unlikely combination of Highland gillie and aesthete…I don’t know anyone else who can skin and gut a deer and has his insights into painting.’

Jeffery Camp Sentinels 2011 Oil on canvas 30 x 30cm

John McLean Cantabank1999 161 x 223cm