Recently my daughter Athena has become interested in the large books that line one wall of our sitting room. Most of these are exhibition catalogues, collections of photographs or works of reference: Alasdair Gray’s A Life in Pictures sits alongside several volumes of the Survey of London, and Don McCullin’s In England caps a pile that includes a couple of atlases, a cheap edition of Gustave Doré’s illustrations for The Divine Comedy and Frank Ching’s Visual Dictionary of Architecture.

Athena likes the photobooks best, and she’s especially drawn to Martin Parr. Of the Parr books, The Last Resort is the one that has captivated her. Published in 1986, it’s a collection of photographs taken in New Brighton on the Wirral peninsula, about five miles from Liverpool. Once a bustling holiday destination boasting Britain’s biggest lido, it is perhaps best known today for a connection with The Beatles, who played at its Tower Ballroom more than twenty times between 1961 and 1963.

When Parr visited, as he did repeatedly in the mid-1980s while living nearby, New Brighton seemed to offer a perfect opportunity to document the contradictions of English leisure. Untidy and in a state of crumbling decline, it was nevertheless a temple of consumption—a place for pursuing amusement, albeit mainly with an assiduous lack of cheer. Critics interpreted the series of photos he took as an indictment of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain and a vision of the north-west’s post-industrial slump. But they also found it peculiarly ungenerous, a condescending portrait of working-class life.

Robert Morris, in a pretty representative write-up for the British Journal of Photography, argued that The Last Resort evoked “a clammy, claustrophobic nightmare world where people lie knee-deep in chip papers, swim in polluted black pools, and stare at a bleak horizon of urban dereliction.” Morris complained that Parr had “obviously exaggerated the negative aspects of the town,” since “it seems hard to believe … that such an awful place really exists.” Other commentators shared his sense that this was a cynical and depressing production.

Leafing through my copy of the revised 2008 edition, I see it in a different light. I feel the guilty pleasure of the prolonged gaze and of intruding on moments that none of the subjects would have been all that keen to preserve. Yet the sharpness of Parr’s attention isn’t hostile, and, while he views his subjects with detachment, there’s an affection for their resilience.

Technically, The Last Resort marked a shift in documentary photography. Parr shot in colour rather than the black-and-white he had previously favoured, and wielded not his usual 35mm Leica, but instead a 6x7cm rangefinder camera (a Plaubel Makina 67) with a 55mm lens. The larger format enabled him to capture a huge amount of detail. Frequently using fill-in flash, he achieved a highly saturated hyperrealism. Every detail is vivid, and the images have a flatness that denies us the privilege of focusing on some central feature. “They are anti-postcard pictures,” Parr has said, and it’s true that they’re about as far away as possible from being mementos of elegant tourism.

“The sharpness of Parr’s attention isn’t hostile, and, while he views his subjects with detachment, there’s an affection for their resilience”

As I write these words, Athena is chewing the corner of the book and scraping her fingernails along its binding. I claw it back and remind her that it’s more than just another teething device. I can tell that she appreciates the images’ bold colours and immediacy. Beyond that, I can’t be sure of what appeals to her most, but she seems intrigued by the representations of English stoicism and reserve: the eyes averted from piles of litter, the willingness of sunbathers to lie on concrete with nothing more than a thin towel to serve as a cushion, the ranks of day-trippers unfazed by others’ stifling proximity, the birdlike pensioners sheltering from the rain.

I’m struck by how many of the photos are of babies and young children—one at the controls of a model tank, another wailing frantically, a third studiously brushing her mother’s hair, a fourth shooting a quizzical look at Parr during an alfresco nappy change. A bonneted toddler, a busy little blur, appears to have escaped from its pram and is hugging the lower portion of an arcade machine. A boy approaches the task of opening a crisp packet as if he’s defusing a bomb.

A few of the children are completely naked, which I suspect would now be more widely frowned on than it was thirty years ago. Their attitude to their own nudity varies: it’s a matter of convenience, a bid for freedom, awkwardly exposing, or simply an unremarkable fact on a hot afternoon.

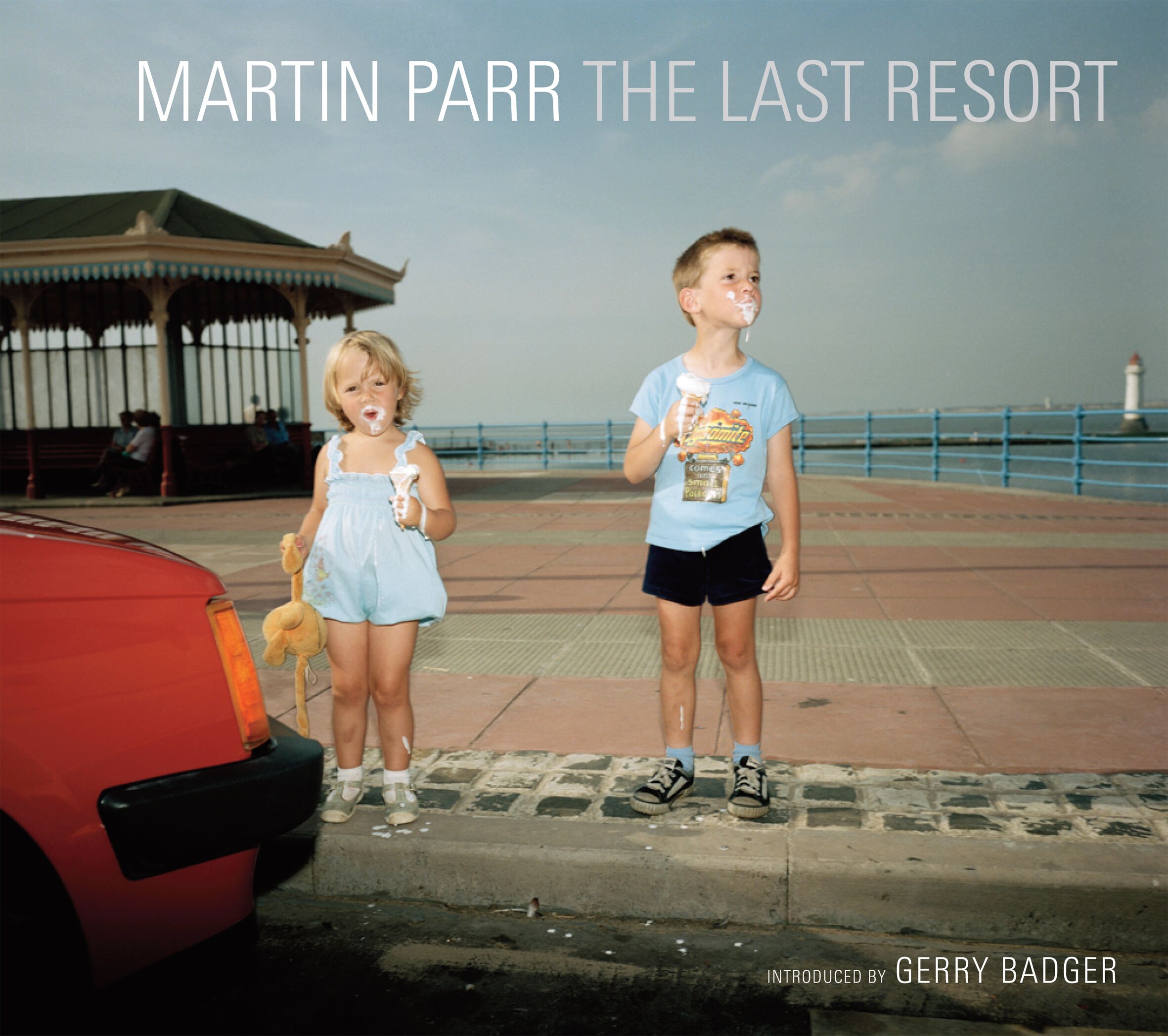

The cover of the volume shows a girl and a boy (both clothed) who’ve been consuming ice creams with artful incompetence. Why nibble decorously, eking out gratification, when in one go you can shove half a cornet in your mouth, experience a rush of arctic ecstasy and have a sticky white beard to show for it? When I think about doing just this, I recall that as a child I never much cared for a dripping cone of vanilla, and I picture some of the summer staples I preferred: the Fab, the Zoom, the strawberry Mivvi, and Wall’s Dracula which turned my tongue an alarming shade of red.

Inevitably, I look ahead to conversations I might have with Athena about which sugar-glutted confections she can have from the ice cream van, and I imagine going with her to the seaside. I’d like it to be somewhere more sedate than Parr’s New Brighton, but so far her two impromptu seaside visits have been to a rainswept North Norfolk and Margate amid the exuberance of Pride—both of which have had their Martin Parr-ish elements.

In Galicia, the Cyclades or the wild islands of the Adriatic, being by the sea means something different, but it’ll be a while before Athena treasures rolling dunes and craggy backdrops, hidden coves and unhurried afternoons. For now her eager embrace of all things that clatter, pop and whir, together with her enthusiasm for strong colours and high contrast, makes her a candidate for very British days out.