Traditionally, the word lesbian has been used to describe female sexual attraction to other women. Today, the term has come to represent a more fluid range of identities as our notions of gender and sexuality have evolved (or, you could argue, the mainstream has caught up with the spectrum of identities that already existed). London’s Lesbiennale, an arts festival that celebrates lesbianism, was in fact curated by two people of colour who identify as non-binary—Naeem Davis and Nadine Ahmad, who respectively run QTBIPOC+ collectives BBZ and Pxssy Palace.

When initially approached to run the festival, they both questioned their relationship to the descriptor, particularly regarding gender and its intersection with sexuality. Ahmad, during a feature with Go Mag

, explains that “there was a romanticism over the word that was denied to me for so long because of the binaries that I felt existed.” During the interview, writer Clare Hand summarises the spirit of the term: “Like the word ‘queer’, lesbian can be expansive, limitless, and amorphous.”

“The archive paints a visual and aural timeline, from cassette recordings of Audre Lorde’s speeches to the visceral photos of protest marches”

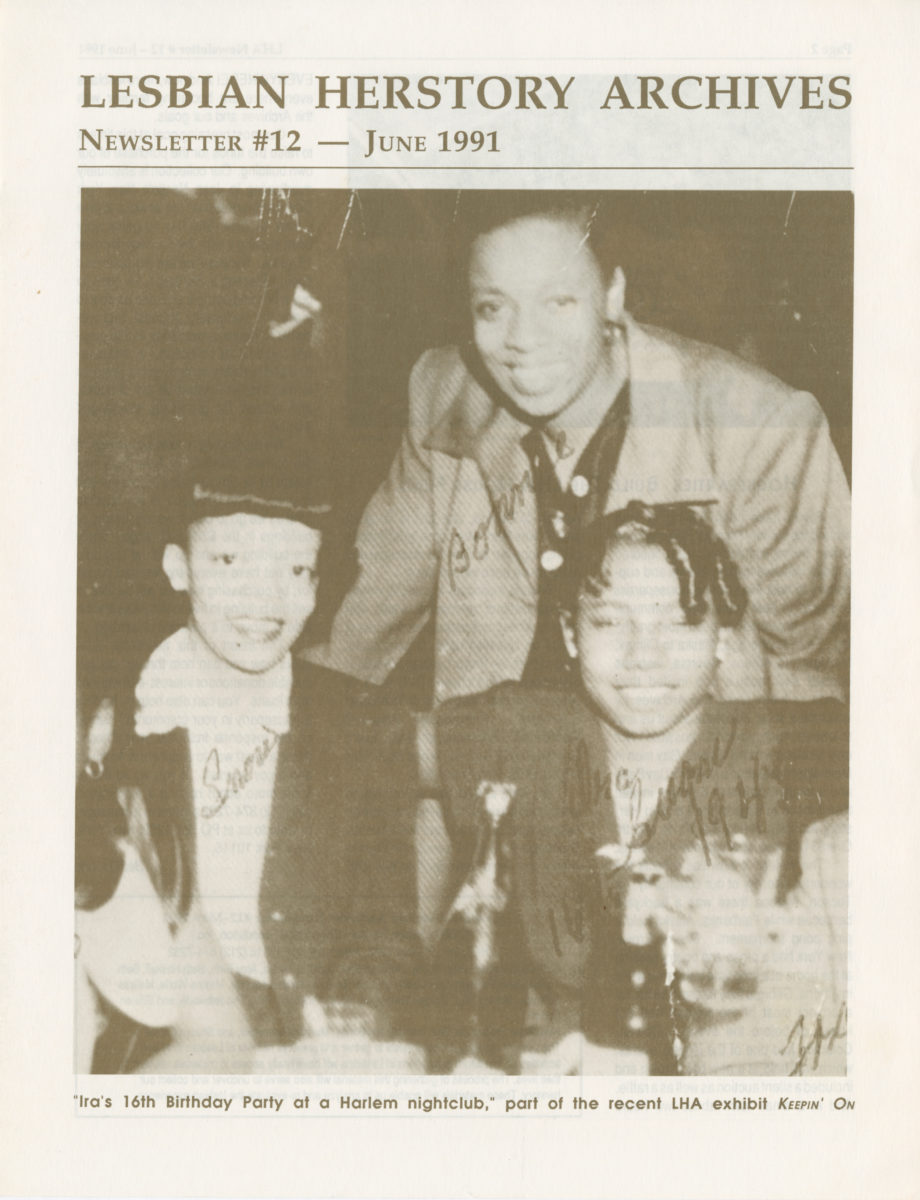

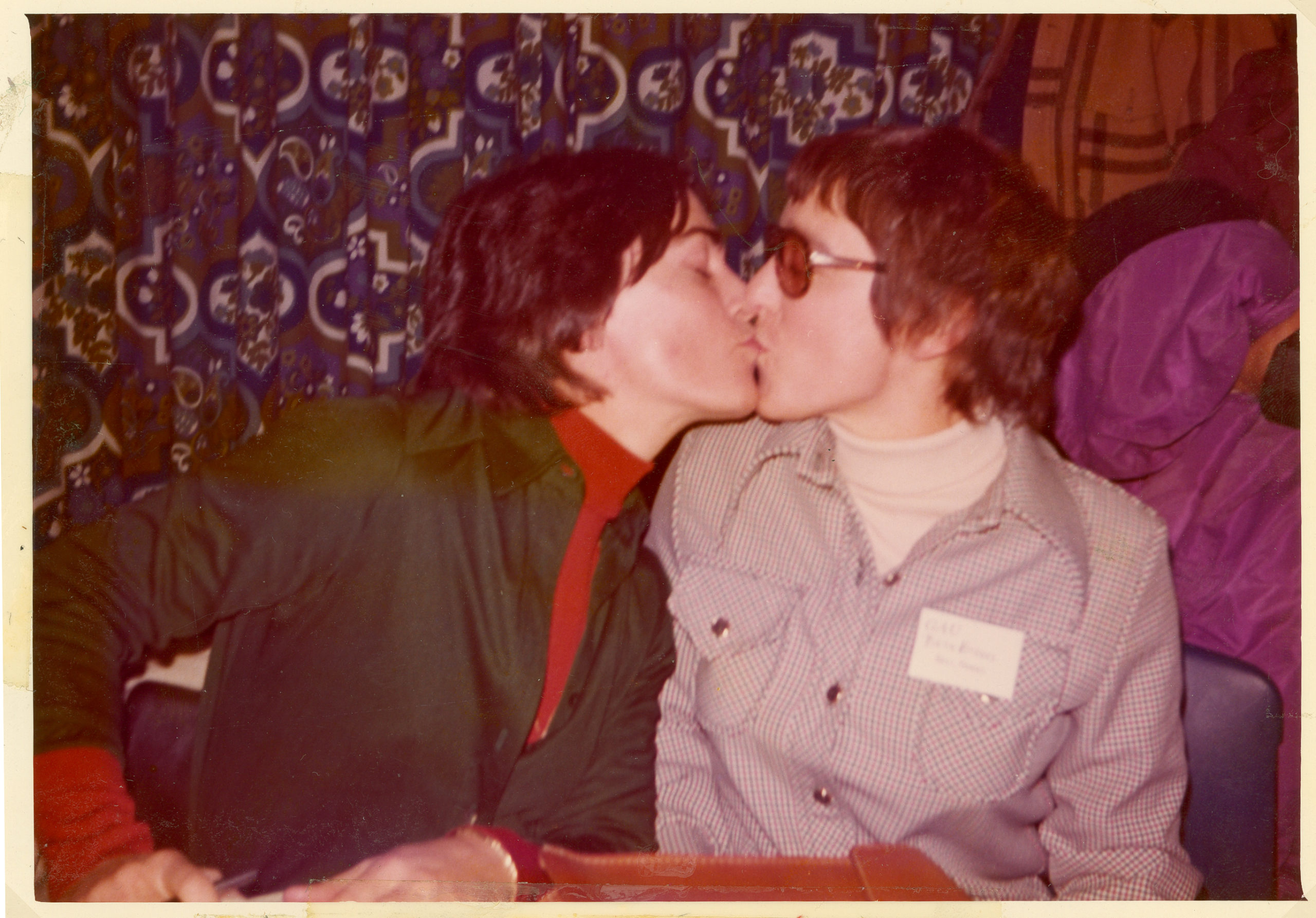

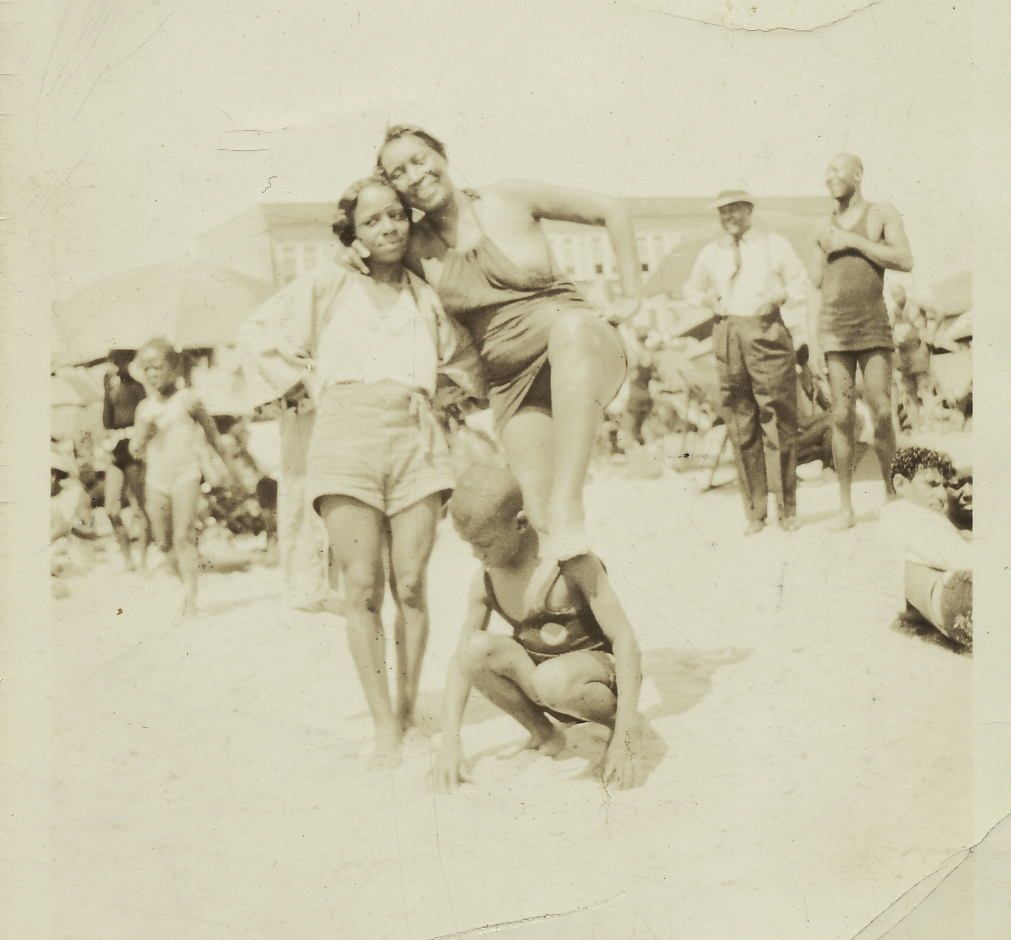

For this reason, it’s essential to look to history (or herstory) for examples of the true length and breadth of lesbian culture, and the identity politics associated with it. The Lesbian Herstory Archives, situated in Brooklyn, New York, do a fantastic job of collecting, preserving, and categorising these stories. Their website homepage proclaims that the LHA is “home to the world’s largest collection of materials by and about lesbians and their communities.”

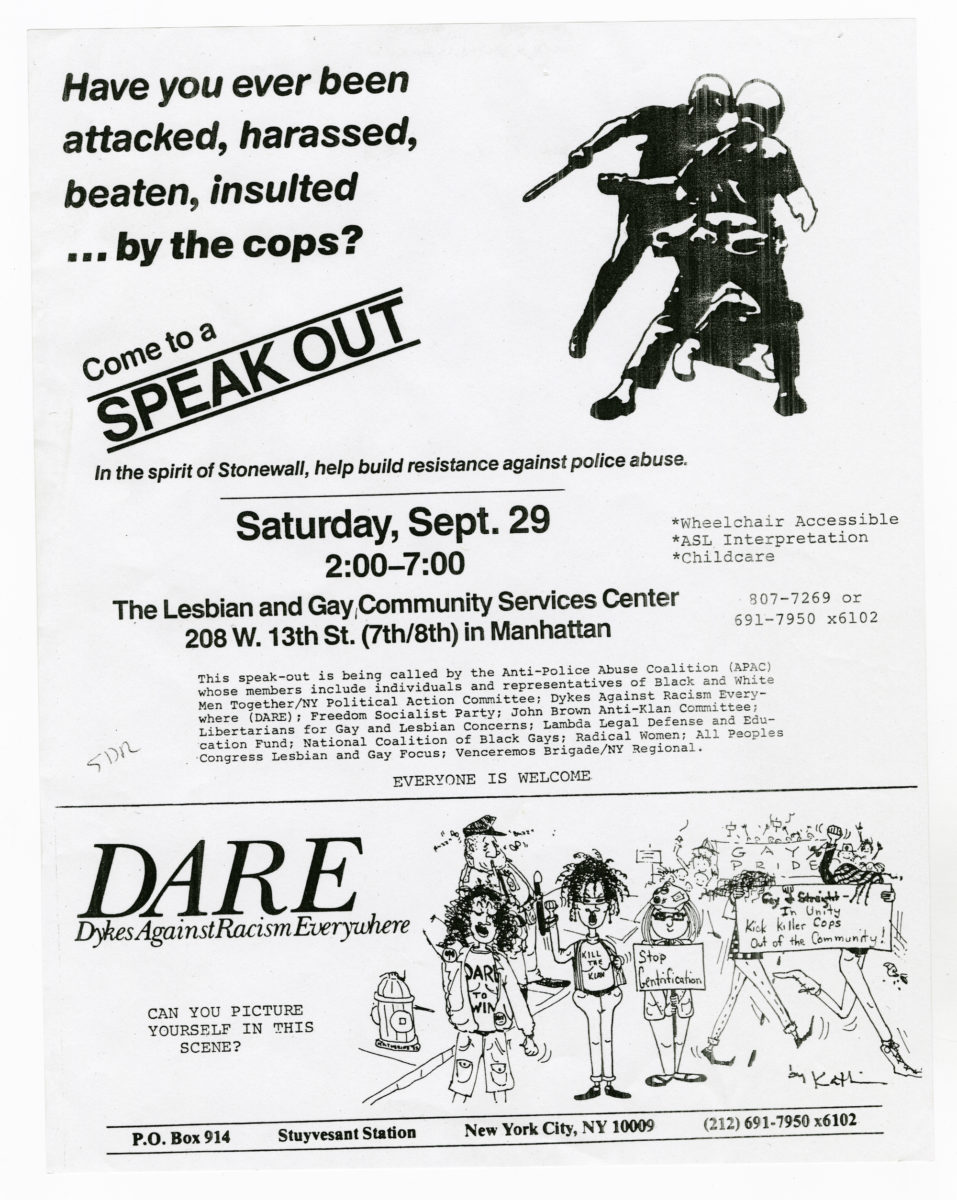

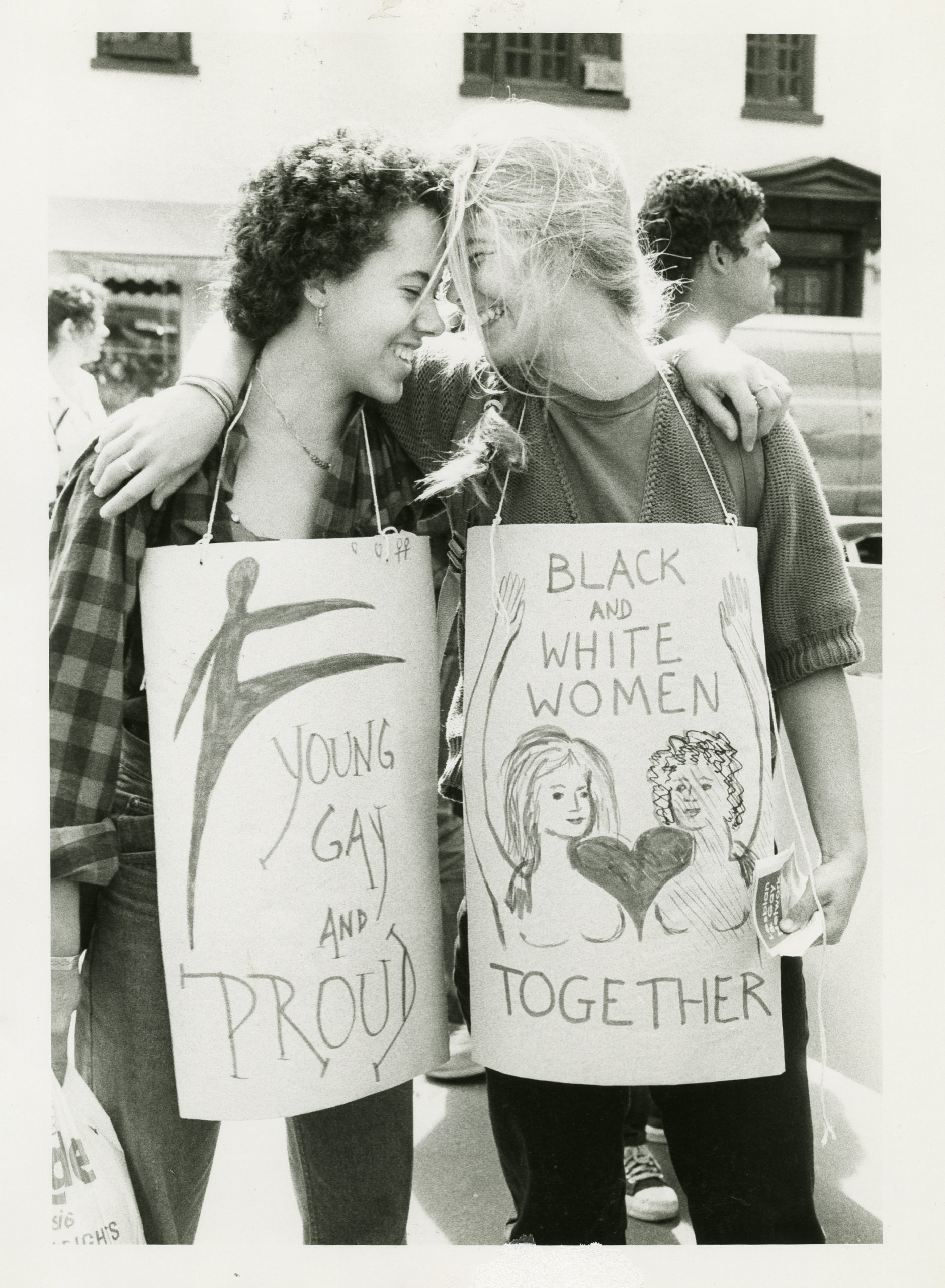

The archive paints a visual and aural timeline, from cassette recordings of Audre Lorde’s speeches to the visceral photos of protest marches. Much of the material is available digitally, increasing public accessibility to stories where they can see themselves reflected.

The project gathers together this ephemera; speeches were recorded, pamphlets preserved and photographs taken in a bid to write gay women into history. There were certain individuals who made the archives what they were by donating their personal collections. Mabel Hampton donated her extensive collection of 1950s lesbian paperbacks and often came to volunteer nights to relate her stories. Women from completely different walks of life would gather to listen, enraptured, to Hampton’s tales of drag balls in Harlem.

Alongside Hampton was Georgia Brooks, an activist who launched the first Black lesbian studies group, and Judith Schwartz, a pioneering lesbian historian. These individuals came together to pool their diverse skill sets and form a community that offered solace from the heteropatriarchal outside world.

“Women from completely different walks of life would gather to listen, enraptured, to Hampton’s tales of drag balls in Harlem”

Some of the most powerful audio recordings are those of Audre Lorde, whose words galvanised so many to action. Best known for her powerful poetry, she was also a famed theorist, and spoke at many conferences on lesbianism, Black feminism, women’s literature and more importantly, the intersections of these topics. At one conference on feminist theory she proclaims—”Why weren’t other Black women found to participate here? Why were two phone calls to me considered a consultation? Am I the only source of names of Black feminists in this country?” She goes on to lambast the lack of interracial cooperation on women’s issues, a topic which sadly sees itself reflected in contemporary feminisms.

These fragments of history, pieced together with painstaking care by the curators of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, provide an opportunity for current social justice movements to learn from the past. As a Black lesbian woman declares during footage from the San Francisco Dyke March and Gay Pride—‘Dykes historically have always led the march for freedom.’

All images courtesy Lesbian Herstory Archives