The Moomins, the creation of Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson, are one of those things which, while strictly belonging in the children’s category, nonetheless have a subtle depth and complexity that many adults will always find appealing.

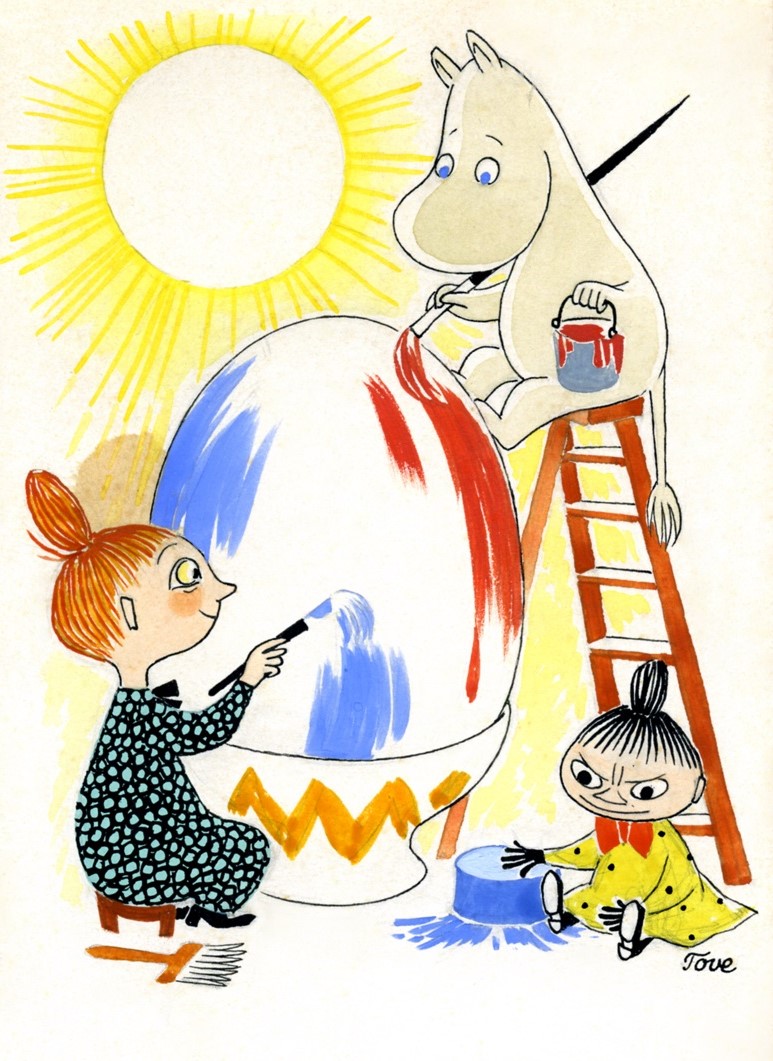

There has been something of a global Moomin boom since Jansson’s death in 2001, meaning that the characters from her nine novels, numerous comic strips and countless illustrations are easily recognisable. Moomintroll and his parents, Moomin Mama and Moomin Papa, possess a delightfully innocent appearance with their bulbous noses and round tummies. The cartoonish features and enormous eyes of the hippo-like creatures have perhaps inevitably found particular popularity in Japan.

However, despite the Moomins’ popularity and commercial potential, Janssen was determined that she would avoid the sickly sweet caricatured fate of other rotund childhood companions, such as Winnie the Pooh, eschewing requests from the Disney company to turn her characters into simplistic bundles of animated joy.

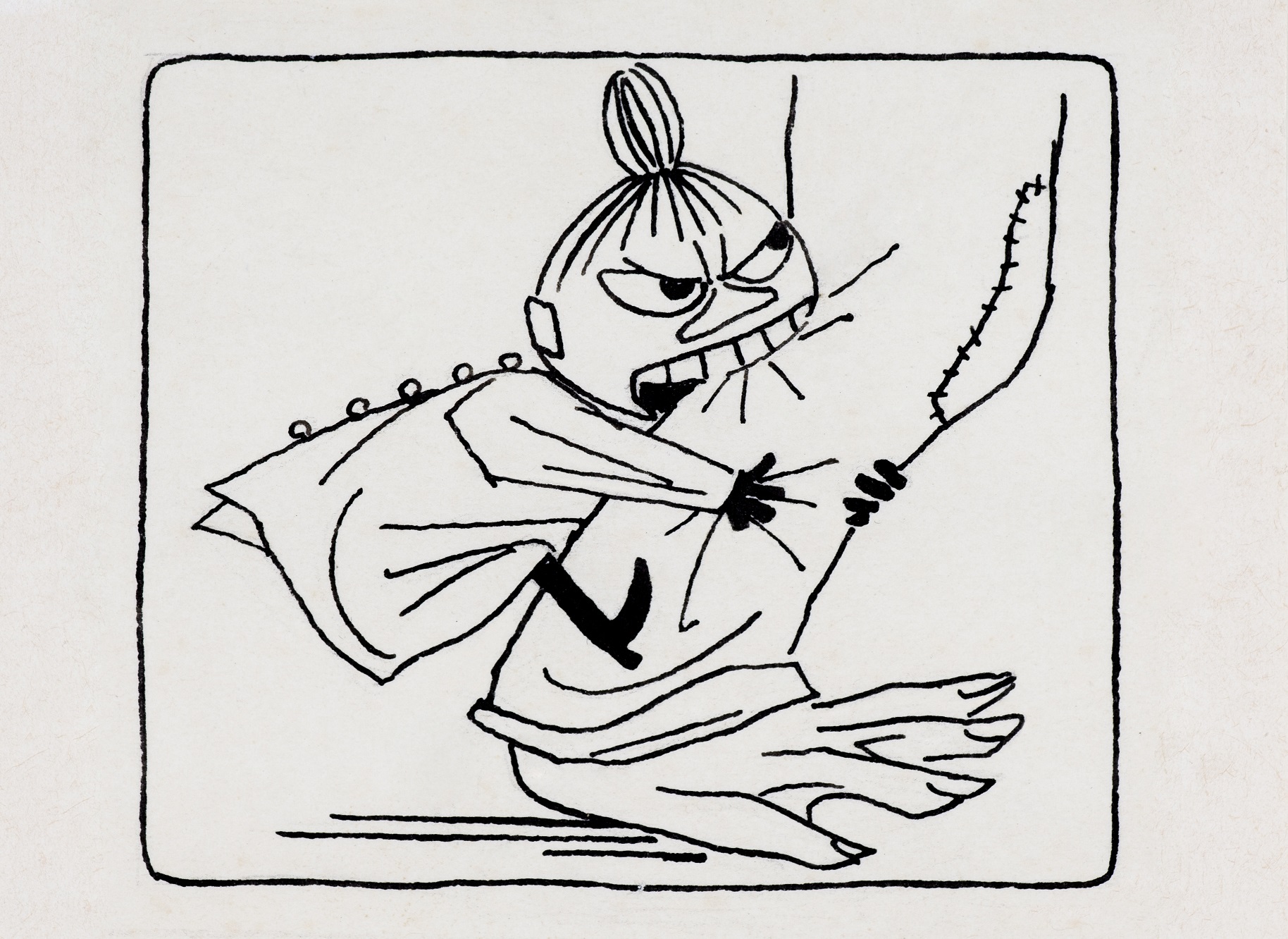

While it is certainly true that the Moomins have widespread appeal, this is not due to a bland moralistic accessibility, and Jansson was never one to dwell in banal, infantile delight. Her illustration of the very first Moomin—an attempt to draw “the ugliest creature imaginable”—was in reaction to a philosophical disagreement about Immanuel Kant with her brother, a decidedly unusual point of contention between bickering siblings. Jansson remained precocious and critical as she grew up. She wrote and illustrated her first book at the age of fourteen, and had her mocking illustrations of political figures, such as Hitler and Stalin, published in the Finnish satirical magazine Garm from fifteen.

Indeed, if Jansson had known that her primary legacy was to be the fantastical Moomins, she might have been slightly irked. Born to a family of artists, she saw herself as a painter first and foremost. While her Moomin creations brought her fame, she struggled with the feeling that their popularity had eclipsed what she saw as her real work. In 1959, with six of the eventual nine Moomin novels under her belt, she wrote “My life with Moomintroll has begun to resemble a very worn-out marriage. Now I draw Moomins with a feeling that is starting to resemble hatred.”

“It is true that the Moomins have widespread appeal, but this is not due to a bland moralistic accessibility, and Jansson was never one to dwell in banal, infantile delight”

While Janssen’s occasional resentment of the Moomin family is not obvious in her books, there is, nevertheless, much of Janssen’s personal reality to be found in her creations, with many of the characters representing her own friends and family. With same-sex relationships illegal in Finland at the time, she hid clues to her illicit loves in her characters. Thingummy and Bob represent Jansson and her married lover Vivica Bandler, while the character of Too-Ticky is based on the love of Jansson’s life, Tuulikki Pietilä.

It’s not just the people who Jansson was close to that are represented in the Moomin world. Written during World War Two, with Jansson’s brother fighting in France, her first two Moomin stories, The Moomins and the Great Flood (1945) and Comet in Moominland (1946), reflect that peculiar melange of terror and everyday mundanity characteristic of the civilian war experience. While radiating messages of acceptance more classic to children’s literature, there is nonetheless an underlying recognition that sometimes, no matter how pure and true your heart, terrible things will happen to you—even if you are a charming, adorably porcine, happy-go-lucky, fantasy creature. They are not your classic light and breezy children’s books, and yet there is something comforting in their message. It’s the reassurance that even if everything is terrible, it doesn’t mean that the world is irredeemable.

The ninth and final Moomin book, Moominvalley in November (1970), written just after the death of Jansson’s mother in 1970, is laden with her grief. Her loss echoes in every word and line. And yet the darkness isn’t total, and the grief isn’t all-consuming. There’s a pleasure in the little things. Screenwriter and novelist Frank Cottrell Boyce said of the stories, “One of the things I really took from them was the importance of small pleasures, that life is really worth living if we’re just nice to each other and make really good coffee, and the pancakes are just right. Then nothing else really matters in any substantial way.”

The Moomins aren’t meant to represent an unflinchingly banal harmlessness or a sparkling happy-ever-after. There is a darkness inherent throughout, but also there is the ever-present suggestion that it is a darkness we can cope with. Tove Jansson’s creations and words speak to adults who know, just as well as she did, that death and depression are a reality, and that often it’s the little things, like really good coffee, that can keep us going. We don’t want to be told that we’re the only ones who are failing to be unceasingly lucky and unflinchingly cheerful. We want to know that we are not alone.