Aindrea Emelife and Yinka Shonibare Kick off a Nigerian Renaissance on Their Way to Venice

It is an interesting time to be sitting down with burgeoning curator Aindrea Emelife and renowned artist Yinka Shonibare. Once again, their names are on the world stage as Emelife is in the midst of curating Nigeria’s pavilion for the Venice Biennale–the second ever pavilion for the country featuring the epochal work of Shonibare as well as seven other artists from the Nigerian diaspora. The two, who have both split their lives between Nigeria and London, talk slowly with me on a Monday afternoon, crowds of Londoners swelling outside their respective apartments celebrating the Summer bank holiday. But inside, these two were a land away, transporting us to the heart of Lagos, and conspiring on how to transmit that pulse to Venice in 2024.

If I’m continuing on with medical analogies, with all seriousness, this is a life saving operation. Nigeria is in the midst of an artistic renaissance of sorts. The country is preparing to open the new Museum of West African Art after years of construction, also slated to open in 2024 and of which Emelife is curator of contemporary and modern art. The new museum will be essential to not only inspiring a generation of young Nigerian’s with access to the world’s art, but will be a homecoming for a variety of restituted African art stolen during the colonial era. But while it may feel in some ways that this is just the beginning of what Nigerians can bring to the art world, it is Emelife and Shonibare’s mission to utilize the Venice platform to dispel any of these preconceptions.

“I think what is poignant is what it means to articulate a nation, which is really difficult for Nigeria, which is made up of hundreds of different tribes and languages and is way more diverse than people realize,” shared Emelife. “Articulating a national pavilion…It’s quite unlike other exhibitions. I think they have the great potential to shift perceptions, to introduce narratives that have always been there–and shine light on the historic, as well.”

It is remarkable to watch Emelife and Shonibare go back and forth in lockstep, and it is clear that they share the same artistic vision and aspirations for the pavilion. “I think that’s something that’s really fundamental to me. The historical and heritage,” shared Shonibare. “Where have we come from? Why are we where we are today? And what’s the impact of the past on the present? Those things are very important, because until we start to actually understand the past, it’s almost impossible to understand the present.”

This is the thought process that culminated in the theme for the pavilion, Nigeria Imaginary. “It is critical to reflect on the past. But it can also be utopic,” shared Emelife. “I think about the youth of Nigeria–the stat is around 70% of Nigerians are under 30. It can be a great opportunity for people to think bigger and dream harder. Knowing how diverse and talented we are, we can really investigate our history to carve out a new renaissance.”

Investigating that history is integral to the entire operation. “It’s important that we start to restore our self esteem as Africans,” shared Shonibare. “We grew up, you know, basically under the influence of colonial rule. That does something to your psyche. The whole idea of slavery, of race theory in the 19th century, and then what’s happened to our people–both within the continent and then in the diaspora. We need to actually claim back our memory and our heritage. And through art we can explore those things. We can restore some of our self esteem. I think the Biennale platform will allow us to do this.”

Nigeria Imaginary will feature a variety of artists of Nigeria and its diaspora, including Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Ndidi Dike, Onyeka Igwe, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Abraham Oghobase, Fatimah Tuggar, Precious Okoyomon, and Yinka Shonibare. Each artist’s work will represent a different generational and disciplinary perspective. “I thought it was important that we have artists that work in a variety of different mediums that dispel the idea that African art is just one thing, because I still think that lingers in people’s minds,” noted Emelife. “Without revealing too much, all the artists have chosen very different aspects of Nigeria, and in some instances, Nigerian history to focus on. It shows the great breadth of material and of history that there is to follow.”

Part of the work Emelife has before her is a curatorial structure that emphasizes the uniqueness, the optimism, and the creativity of Nigerian artists against the bag of “Black art” that all Black artists get thrown into. “I’ve been thinking about this whole “Black art is a monolith” thing, and if you drill it down to what people think Nigerian art is. I’ve been devil’s advocate and asked people what they think it is, and I’m kind of not surprised. But in a way I am, because if you think about our history, we have always had such diverse art practices–whether it’s bronze casting, or pottery, or weaver’s, or painters. We’ve always had so many different mediums,” shared Emelife. “I think that Venice is a great place to do away with these stereotypes and these preconceptions, because it’s one of the only places where you really see are articulated by geography in such a way You start to understand your own preconceived judgments more directly.”

It was clear to her from the beginning that Shonibare had to be a part of the project. “Yinka was one of the first people that I thought would be appropriate and necessary for this national pavilion for many different reasons. He’s someone that I’ve been following for all of my life, basically. As a Nigerian British curator, I resonated with a lot of the different ideas that are within his practice.”

I wondered what Shonibare thought of Emelife as well. “I have to say, I was quite impressed. I was really impressed by your enthusiasm, and wanting to do something in a considered way. It didn’t feel like bandwagoning to me. It felt genuine,” shared Shonibare with Emelife. “I’ve seen people who’ve all my years of working, they’ve never had the slightest interest in Africa or to African artists. But all of a sudden, it’s really fashionable.”

What Shonibare says is true. Black art, specifically portraiture, is at an all time fashionable high. And looking back at history, Shonibare is hesitant to celebrate. “I’m cautious because we’ve been somewhere like this before, historically. We’ve had the Harlem Renaissance, and African artists were super fashionable before the war. They were cool, and everybody was talking about, you know, African American art. But then, there was a recession. Then the Depression era. And it’s almost like, many of these artists don’t exist, because through my arts education, I wasn’t taught any of those artists. I found them much later on. Of course, I’m very positive and very enthusiastic. But I do want us to look to something much deeper than just the trend.”

“I definitely agree,” responded Emelife. “I think that’s maybe where the sensationalism comes from, because people think that it’s come out of nowhere, when, as we know, there is a legacy to it. Hopefully, as this is proved, over time, people will understand that this is not just a blip or a moment. This is the root of a legacy that we should have been investigating for a long time.” Ever the optimist, Emelife grasps this reality as an opportunity. “It’s a great opportunity to learn more about the world. Like it’s been a massive injustice that we as humans have had a whole continent, and whole areas and whole decades, hidden from us, or overlooked. And so now we can be excited, wherever we’re from, because it’s as if we’re taking the blinders off. And there’s a whole new world! It’s like, you’ve opened the door to a room that was always there but you haven’t ever seen it.”

Though the Nigerian pavilion is on both of their minds, there is a firm understanding that expanding the idea of Nigerian art takes more than just an exhibition. In 2019 Shonibare founded Guest Artist Space (G.A.S.), an artist residency program in Nigeria, in an effort to bring both African and international artists onto Africa soil for cultural exchange. Given the journey has traditionally been for artists to go to the U.S. or to Europe, Shonibare started the program to help artists to learn from local creatives and educate the world about Africa. “We have to build our own institutions on the ground. We have to do that. Yeah. We should not be waiting for others to do that for us. We need to take control,” shared Shonibare.

“The more people that come to Nigeria and come to Africa, the better. This moment is great, because we’re going to have a lot more exhibitions, hopefully, at all the institutions that we know and love–we’re already seeing diverse programming at the MOMA’s and the Tate’s. But it’s the West benefiting from our artistic legacy again. What will be important is having that same academia, having those exhibitions, having this sense of programming, for us on our own ground,” shared Emelife. “How do we allow our artists and our academics to see art and exhibitions, see our own art and our own exhibitions, and actually be involved in a global art ecosystem. Rather than us having, you know, an artistic legacy being safeguarded and being protected, but being protected outside of the continent?”

The root of Nigeria Imaginary is the sense that is not imaginary at all. It’s very real, and is real for the millions of Nigerians who the West often turns a blind eye to. “It’s important that people actually have the opportunity to experience this culture,” shared Shonibare. “Not in a kind of nostalgic, sentimental way. It’s a way to understand that, actually, I do have a heritage. I do have a history. I’m not homeless. I have my feet firmly on the ground by people who welcome me. And who understand me. You know, and understand why I feel how I feel.”

Written by Shaquille Heath

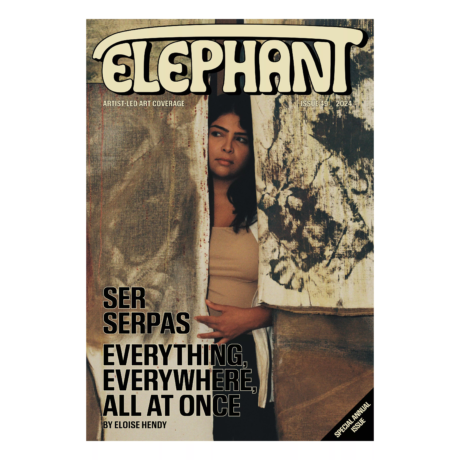

This feature originally appeared in Elephant #49

buy it here