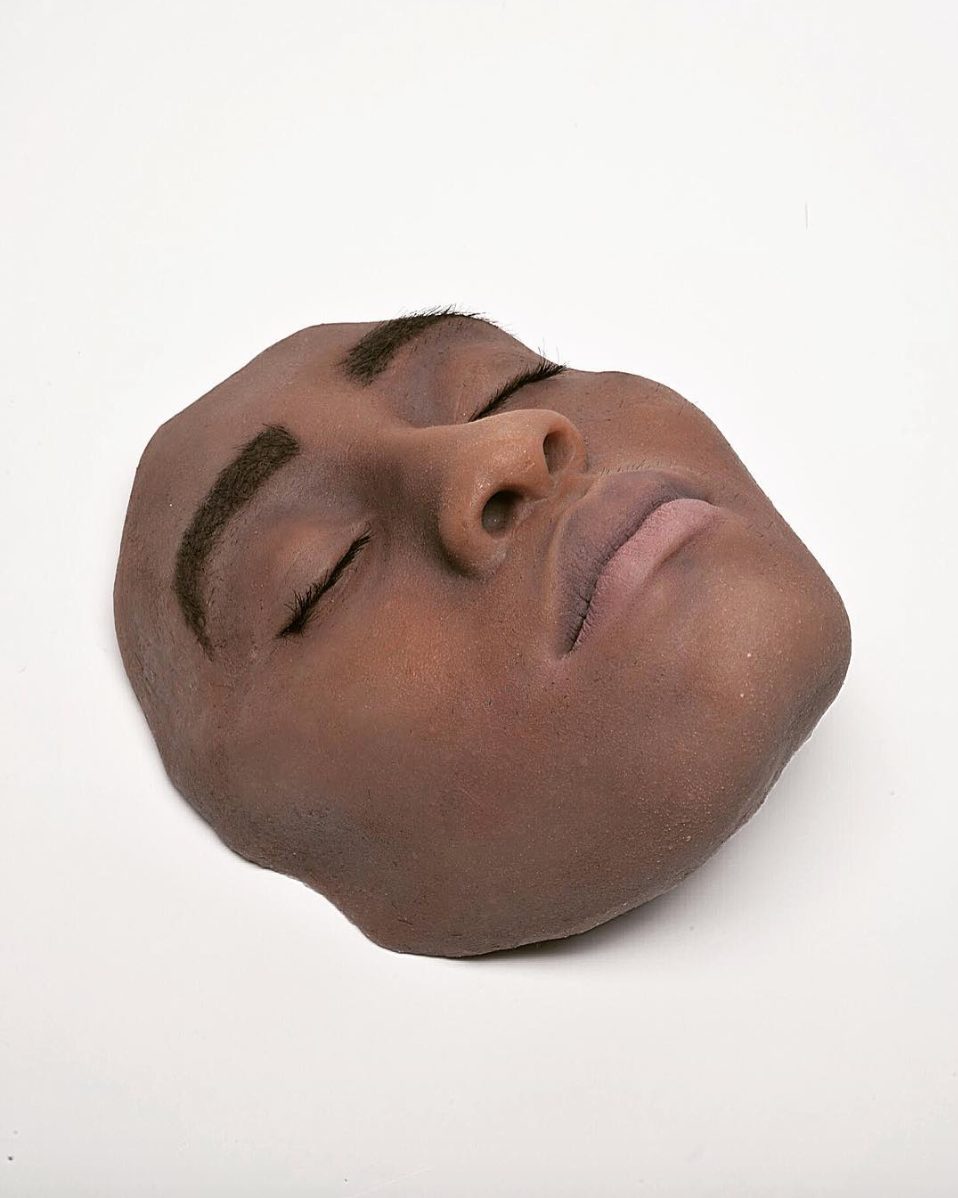

Rayvenn D’Clark is an artist who uses her practice to challenge and renegotiate the longstanding colonial gaze on Black bodies, via the theory of the body politic. Her work hones in on intensely rendered parts of the body, intimate in their detail and startling in their clarity. Harnessing the technology of 3D printing, her creations are in equal parts nostalgic and entrancing in their realism.

D’Clark grew up in South London and graduated from a Masters in Fine Art at Chelsea. She is also junior editor at Shades of Noir, an anti-racism platform that provokes, challenges and encourages dialogue through its programme of activities on the subject of race within art and design education.

- My Head Hurts, My Feet Stink, and I Don't Love Jesus, 2017

When did you first realise you wanted to make art?

I was a kid that was doodling in the corner instead of doing their maths—I remember I started this cool business where people would pay me Capri-Suns and I’d draw them a picture at lunch. It was really when I got to my A Levels that my tutor said “You should think about doing this at uni.” I never thought, until then, that a creative subject was one that I could get involved with. Then, in my second year at university, I was speaking to my dad and he said “You’re gonna have to start calling yourself an artist now.” And that was the first time I’d thought, “Maybe I can do this full time!”

You have written about being inspired by Body Politic theory. How does this manifest within your work, in which the audience is allowed an intimate look at the physical body?

My work would always gravitate towards the figurative, but I never could pin down any theory that I had any kind of affinity to. When I stumbled on the Body Politic, it was the first time I’d ever conceived myself or others like me as a whole. Not to say that we’re a homogenous group, but there’s a collectivity between Black people in general, so the theory stuck with me. It was about marrying the figurative and the theory, and seeing that there’s this inability to cast or capture any one person without that whole being an entirety. Whether it’s their culture or their gender or their sexuality that was encompassed within it as well, there was always this kind of collectivity.

“When I stumbled on the Body Politic, it was the first time I’d ever conceived myself or others like me as a whole”

You are junior editor at Shades of Noir and an Associate Lecturer at UAL. How does academia feed into your process of art making?

Graduating and looking at things from an Associate Lecturer standpoint, you feel all the things that you felt as a student, where you felt totally unequipped to deal with a lot of things that were going on. My knowledge for that in terms of micro and macro aggressions has come from my work at Shades of Noir. It put a fire under my bum to make sure that when I do teach, I’m going to be a different model of teacher, because we all know the system we’re in is broken.

The good thing about lockdown and Black Lives Matter is that we all have to witness what’s going on, because we’re stuck inside, whereas in 2014 and 2015 when BLM blew up, people felt like they could still avoid it. Now everything is mediated through the internet because we can’t see each other. It has made people have to witness and understand what it is to exist as a person of colour in the world right now, whether it’s academically, whether it’s because of the police, or in forms of workplace culture.

You achieve incredible detail with the tool of 3D printing—a hyperrealism. How does this relate to the nuances of an identity that pivots between invisibility and hyper-visibility?

One of the first essays I wrote about was around simulation/simulacra and the simulation of reality, where something feels instantaneously recognisable yet you don’t recognise actually what you’re looking at. And in the reduction of taking the colour out [of the sculptures], I felt there had to be this emphasis on material detail. There was a poignance to how real the faces felt when they were being physically sculpted that when I started to move to digital from handmade, that’s the one thing I wanted to keep, because it’s a simulation of this Black face that you could recognise—they could be a member of your family, or a friend you don’t know yet. So no matter what technology I use, that distinct hyperrealism was there.

Nostalgia can be memorable and unreal, and not necessarily something I was physically connected to. The idea of the body politic is where you become a homogeneous group and that lends to the idea of being invisible and yet hyper visible. I hope other people feel this connection to this being that I’ve sculpted—they’ll never know them but there’s a familiarity around them, whether it’s how their facial features are made up, or their skin tone. Sometimes people say they recognise this certain facial structure from this particular culture, so for me it’s about trying to pull in those elements of feeling rather than saying.

“Nostalgia can be memorable and unreal”

Simulation also plays a lot in when I’m taking objects and reframing them back on the internet. The first face cast I made, I showed it in real life, but when I took a picture and put it online, I could remember for months after I kept seeing the face everywhere. It was so weird how detached it was from my actual profile, being my work, but it was really interesting to see the commentary around it. People have never seen Black faces sculpted with such clarity and such recognisable features, yet they had no clue who I was, who the person was, and I kept seeing it getting reposted everywhere for completely different reasons. On the internet, where anonymity is very easy to achieve, it was like that object was taken away from me. The internet changes that notion of simulation and gives you a wider berth of people who you can present that object to.

What is next for you?

Considering what’s going on, I’ve slowed down a bit, which is good for me. I’ve started going back into my writing and reading, which is important as my work is very much based on theory. I’ve got a few public commissions potentially coming up; I can’t give details yet, but I think they speak to the moment we’re in now.

So I’m hoping to make new work soon, but right now, it’s writing. I think there’s a power in the written word, and in me expressing my thoughts in that way now. That will inevitably lend itself to artwork, but I’m not in a rush. Everything is rough right now; it feels so intense and I don’t like to work from a place of anger or sadness. I like there to be an element of calmness in it, because my work, in the end, remains quite calm.