The world learnt last week that, according to the Marc Quinn School of Allyship, representation precipitates empowerment. The white artist’s decision to install—overnight, unannounced and unauthorised—his own artwork on the empty plinth previously host to a statue of slave trader Edward Colston, since toppled, succeeded in the sense that it highlighted the scarcity of representations of Black women across the gamut of public sculpture. However, as many artists and commentators have subsequently argued, the act ultimately failed, in that it only reinforced the challenges Black artists continue to face in placing their work in the public realm.

The world learnt last week that, according to the Marc Quinn School of Allyship, representation precipitates empowerment. The white artist’s decision to install—overnight, unannounced and unauthorised—his own artwork on the empty plinth previously host to a statue of slave trader Edward Colston, since toppled, succeeded in the sense that it highlighted the scarcity of representations of Black women across the gamut of public sculpture. However, as many artists and commentators have subsequently argued, the act ultimately failed, in that it only reinforced the challenges Black artists continue to face in placing their work in the public realm.

Representation of Black bodies in public space is not a quick fix solution to centuries of systemic racism, especially when Black artists feel locked out of the process. As the sculptor Thomas J. Price pointed out in his recent op-ed for The Art Newspaper, “racism runs far deeper than representation”. Quinn’s self-serving and appropriative gesture declined to acknowledge that the empowering function of representation really depends on who is doing the representing.

“The empowering function of representation really depends on who is doing the representing”

This is a position taken by curator Tanaka Saburi who, along with performance designer Nina Kunzendorf, has launched The Molasses Gallery, a three-month open air exhibition project occupying eleven billboards across some of London’s most diverse neighbourhoods, including Hackney, Camberwell, Camden and Shepherd’s Bush. These works also appeared on the street overnight and unannounced, albeit fully authorised.

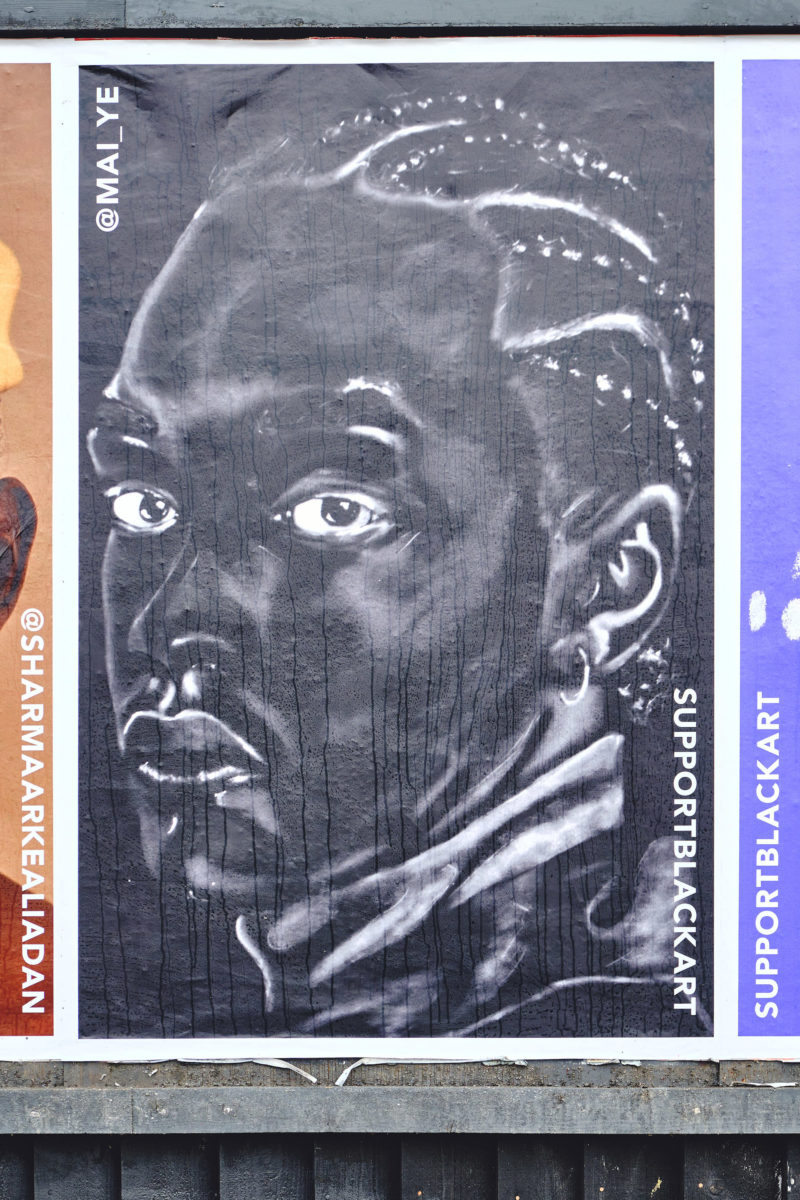

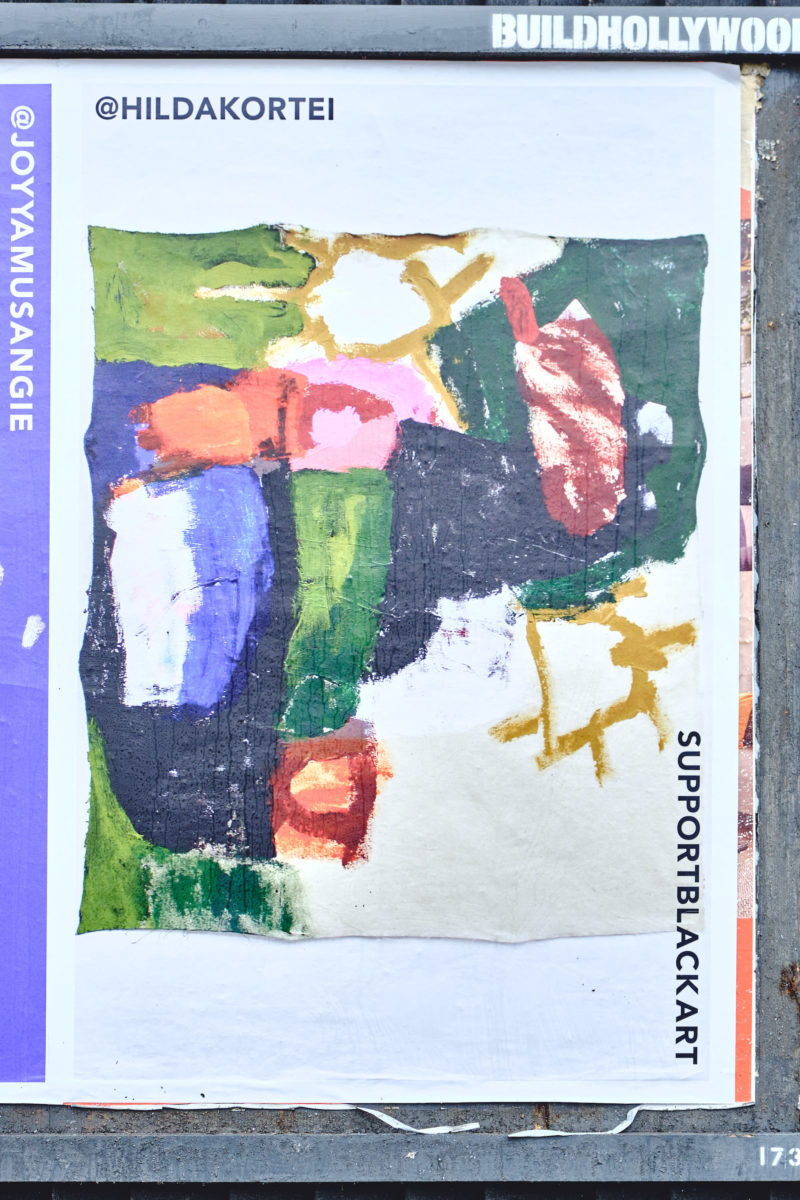

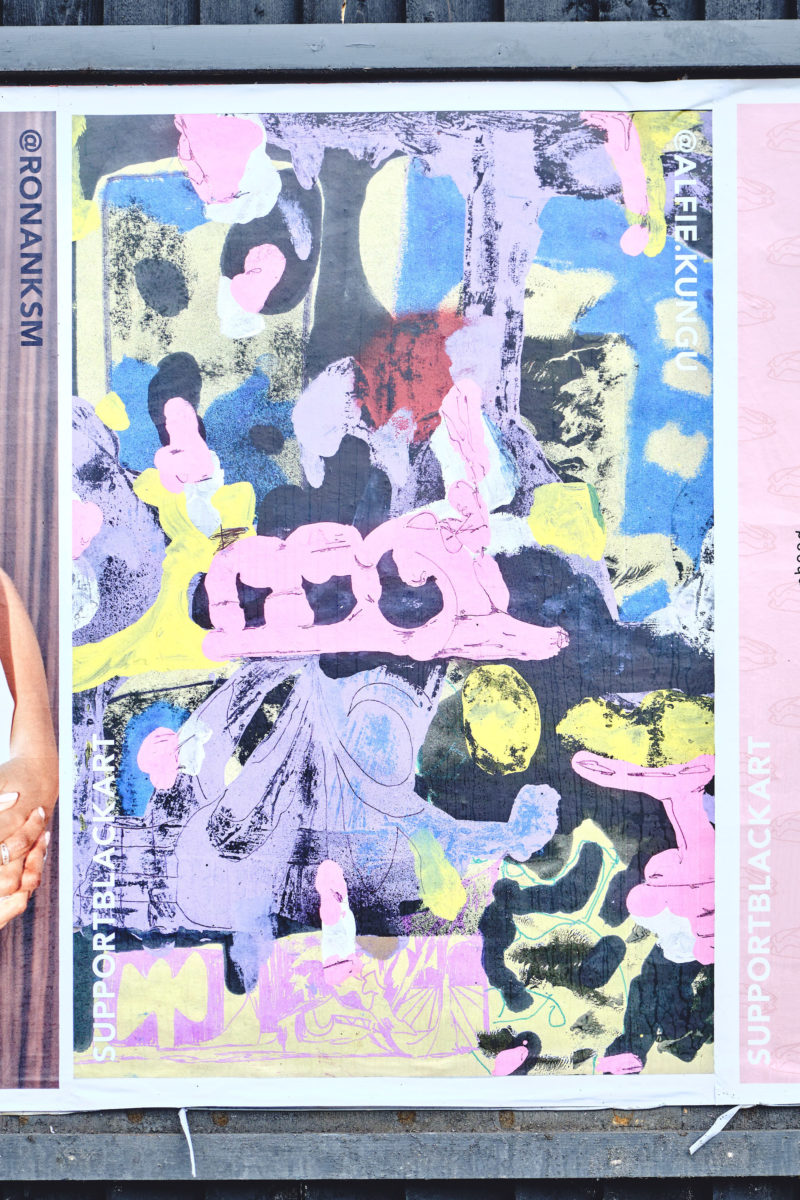

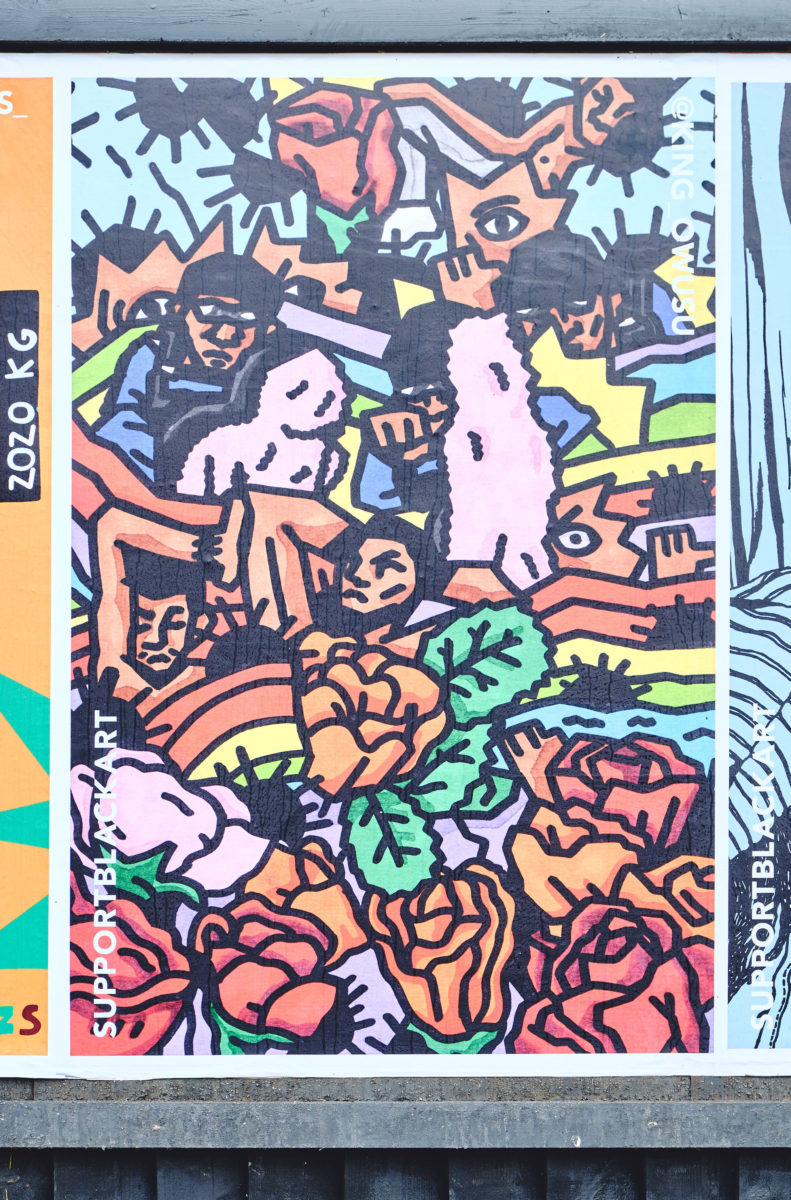

Featuring works by emerging and established artists of African and Caribbean heritage—Alfie Kungu, Ashton Attzs, Chinaza Agbor, Hamed Maiye, Hilda Kortei, Joy Yamusangie, King Owusu, Leah Abraham, Olivia Twist, Sharmaarke Ali Adan, TJ Agbo and Ronan Mckenzie—the initiative is supported by BUILDHOLLYWOOD along with its family of agencies Jack

, Jack Arts and Diabolical, who specialise in arts and culture campaigns in the public realm. The works, which span painting, photography, illustration and graphic design, are framed by the artists’ names and social media handles alongside the project’s unequivocal message: BLACK LIVES MATTER / SUPPORT BLACK ART.

The idea for an exhibition featuring a community of Black artists in London had been in Saburi’s head for some time, along with the link to molasses, which he sees as a powerful Afro-cultural symbol. A major trade commodity across British colonies of the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, molasses was produced from sugar cane grown and harvested by enslaved Africans on plantations across the Caribbean. A sweet, dark and unctuous substance, molasses has assumed a metaphorical function across writing, music and art from the African diaspora. Reflecting on this, Saburi sees molasses as “almost a personification of Black women”. In the wake of the very public murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, the ongoing lack of accountability in police killings of Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain, and the resulting resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, the metaphor adopted a new urgency. For Saburi, molasses is “the biproduct that comes from when Black artists remain creative through adversity”.

Amid the energy and indignation of Black Lives Matter, as Black and minority ethnic people in the UK continue to disproportionately die from Covid-19, the project came together surprisingly quickly. “At such a pivotal time for social justice and change, highlighting the art and activism of Black artists is more important than ever,” Khaly Nguyen, Head of Marketing at BUILDHOLLYWOOD, told me. “We believe art on the street has an important role to play in social commentary and our ethos has always been to use our street space to inspire and energise communities and neighbourhoods. It should be for everyone, it should be made accessible for people to enjoy and learn from, even without access to a gallery.”

“At such a pivotal time for social justice and change, highlighting the art and activism of Black artists is more important than ever”

The artworks on display, whilst diverse in media, share a bold colour palette, decisive lines and a tendency towards figuration. “I was targeting mostly children,” says Saburi on his approach to selecting the artworks. He goes on to talk about parents taking their children to the Tate on a Sunday, a relatively commonplace pastime until the lockdown hit. With galleries closed, and with limited access available once they reopen, the Molasses Gallery brings encounters with art to street level. For participating artist Ronan Mckenzie, the immediate visual impact of the work is profound in its simplicity: “It’s so nice to walk past a billboard that isn’t selling you something, it’s just showing you something nice so that you can enjoy it. Maybe it makes you smile. And then that just improves your day.”

In 2017, in another BUILDHOLLYWOOD project with artist poet Robert Montgomery, billboards on East London’s Commercial Street declared: “Walls are the last gasp of failing ideologies”. It’s a sentiment Saburi agrees with, and he cites Montgomery as an early influence in his development as a curator, after years working in radio and music promotion and later, high-end tailoring. While working in the atelier of the luxury brand Joseph, he staged an exhibition of Montgomery’s work in their Savile Row flagship. “It was just really fun”, laughs Saburi, “but I think I stepped on a few people’s toes at the time”. It became clear that his ideas would ruffle feathers in the stuffy world of Savile Row, where few were interested in fostering the talent of emerging artists, and he started to explore more radical, democratic strategies for exhibition-making.

The language of fashion marketing, which infiltrates the public realm, feeds into the affective capacity of the Molasses Gallery, and other street level art projects like it. Artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Jill Posener and Mustafa Hulusi have long used the apparatus of marketing and its affects in their work. In 2018, artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman launched the 50 State Initiative, a crowdfunded campaign to install 52 artist-designed billboards across all fifty US states, plus Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico.

The language of fashion marketing, which infiltrates the public realm, feeds into the affective capacity of the Molasses Gallery, and other street level art projects like it. Artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Jill Posener and Mustafa Hulusi have long used the apparatus of marketing and its affects in their work. In 2018, artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman launched the 50 State Initiative, a crowdfunded campaign to install 52 artist-designed billboards across all fifty US states, plus Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico.

The billboard itself holds an arguably diminishing status in the paradigms of mass communication under late capitalism, as corporations shift to more insidious, individualised, algorithmic marketing. Nevertheless, billboards and flyposting campaigns contribute to the daily salvo of images that mediate our experience of public space, and artistic statements that subvert those intercessions found especially receptive audiences during lockdown, as leisure activities became a once-daily walk or run in the close vicinity of the home.

“Billboards and flyposting campaigns contribute to the daily salvo of images that mediate our experience of public space”

Especially interesting about art installations, when they creep beyond rarefied institutional spaces and into the realm of the street, is the implicit invitation to the public to enter into a dialogue with the work in ways they wouldn’t in a gallery context. After the Molasses Gallery opened, the organisers discovered that a printing error meant some posters of Olivia Twist’s work were missing her name. Before Saburi could arrange a reprint, members of the public had written in Twist’s name at every single location where it was omitted, in what felt to Saburi like an affirmation of support for the spirit of the project.

Last week, a painting of a reclining Black nude by Chinaza Gabor was torn down from the Molasses Gallery’s Stoke Newington installation in a suspected act of bigotry. Before it could be replaced, a member of the public had used a thick marker on the torn paper to reassert that “BLACK LIVES MATTER”. Each iteration of the Molasses Gallery has become a site for conversation, debate and affirmation, as ownership and authorship is extended across the traditional divide between artist/curator and their audience.

As well as promoting Black artists, Saburi hopes projects such as the Molasses Gallery will also encourage Black collectors. Mckenzie wants to go further, with plans to open her own gallery and project space in North London already apace. “I feel like the art spaces that are really beautiful to go to are either extremely exclusive, or never show Black artists anyway”, Mckenzie explains. “You have to be like, 50 or 60 or dead by the time you get a show.” She cites the high ticket prices of major survey shows such as Soul of A Nation or Get Up, Stand Up Now as a barrier to participation for artists from underrepresented backgrounds. She also laments the tiny number of Black-owned and run galleries in London, or art spaces that explicitly support these artists. “We need a space that prioritises BAME artists from the outset. And it’s not just an afterthought.”

Mckenzie’s plans for the space, which will be called HOME, include a daylight photography studio, gallery, library and event space. But can traditional systems of showing and selling art really be reformed to be more inclusive to Black artists, or must the system be abolished and rebuilt? “I don’t think you need to be abrasive to make a change”, says Saburi. “If you’re going to change someone’s perceptions on a subject they’re unfamiliar with, you have to converse, you have to understand that point of view. And then hopefully, if they have an openness of mind, they will understand yours.”