In 1990, Cammie Toloui started working at the Lusty Lady strip club. A young punk in a feminist band named Yeastie Girlz, she took the job to help fund her photojournalism degree at the nearby San Francisco State University. She ended up staying for three years, working on a peep show stage and in the Private Pleasures booth.

In the peep show she danced with other women, for customers who looked through several windows; the punters paid a dollar and a screen lowered to give them a view, until their money ran out. In the booth Toloui worked alone, performing for just one person, couple or group; each side was able to see the other through a window, and they could talk via a microphone. There the rate was $5 for three minutes.

Toloui had been at the Lusty Lady for about six months when her photojournalism tutor gave her class an assignment, to photograph their own lives for a week. Toloui decided to include her work at the Lusty Lady and shoot it from her point of view, reasoning there were already plenty of images of naked ladies.

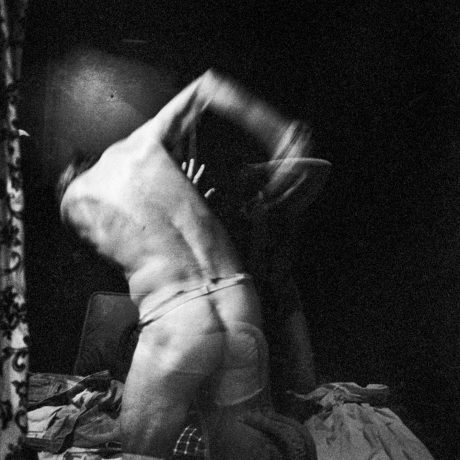

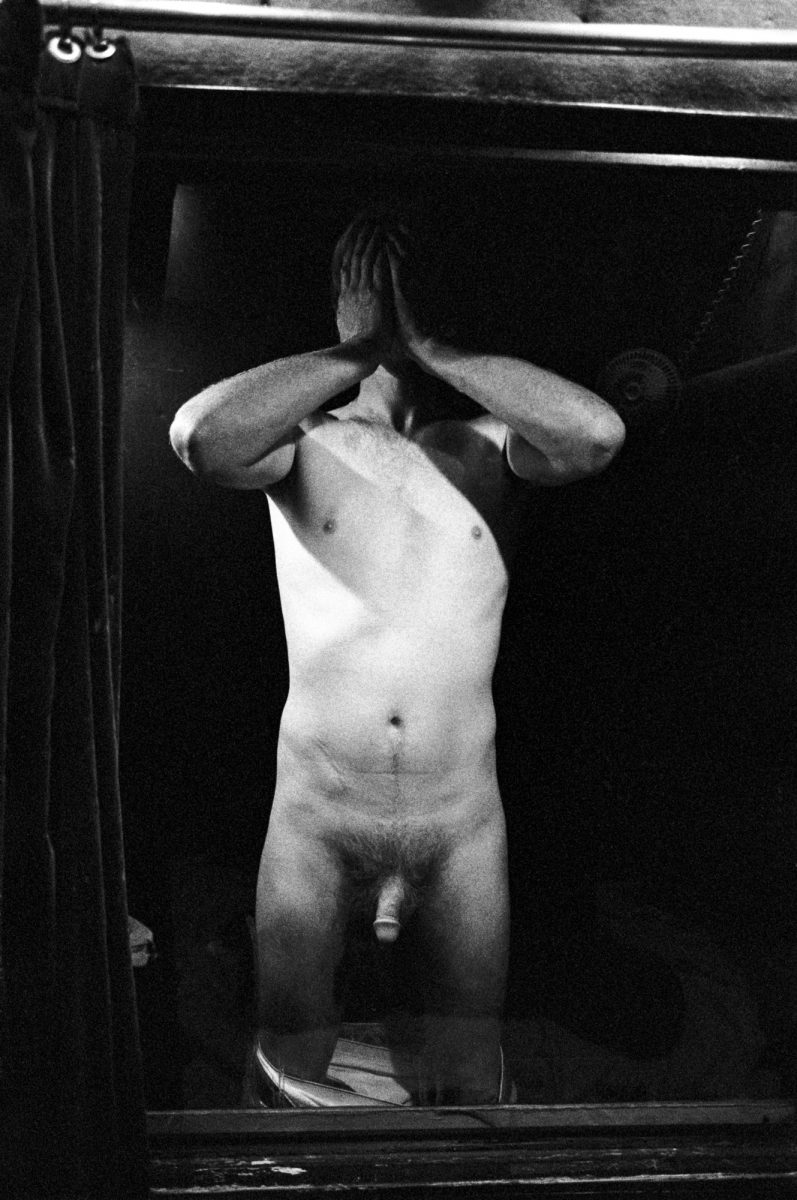

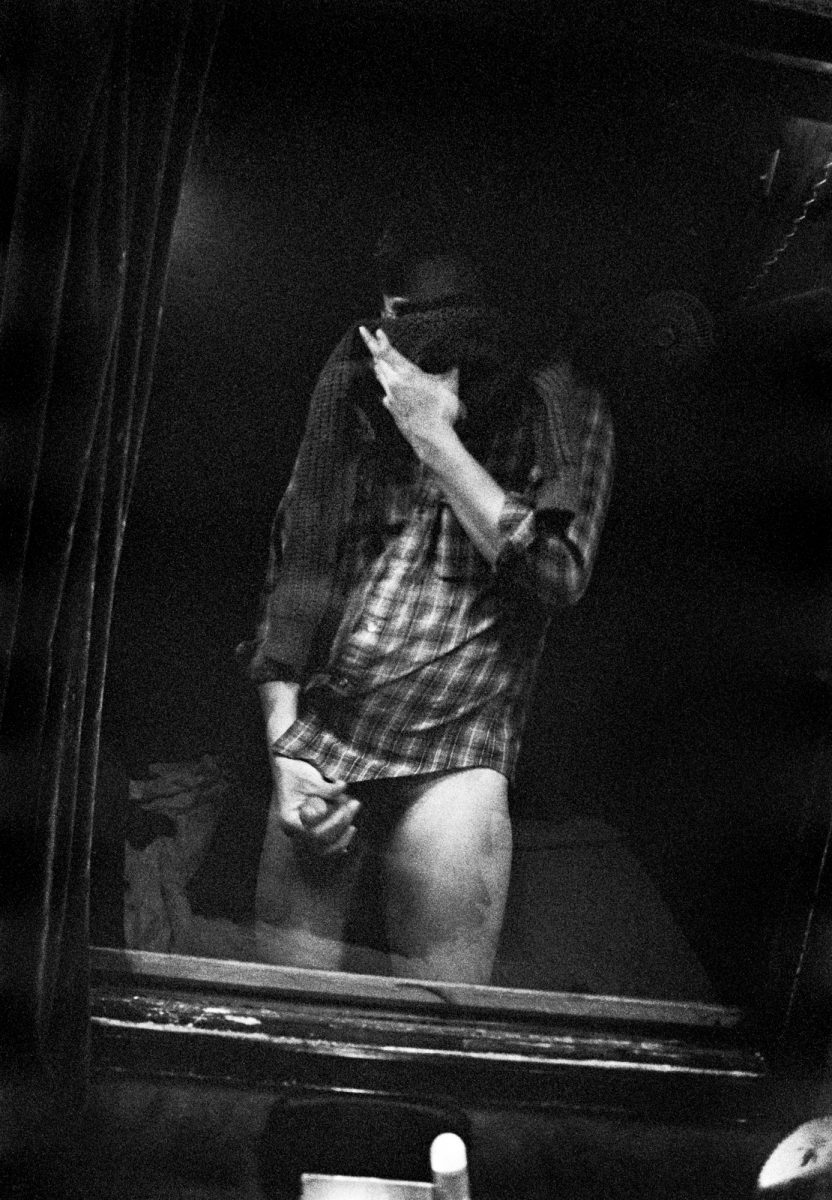

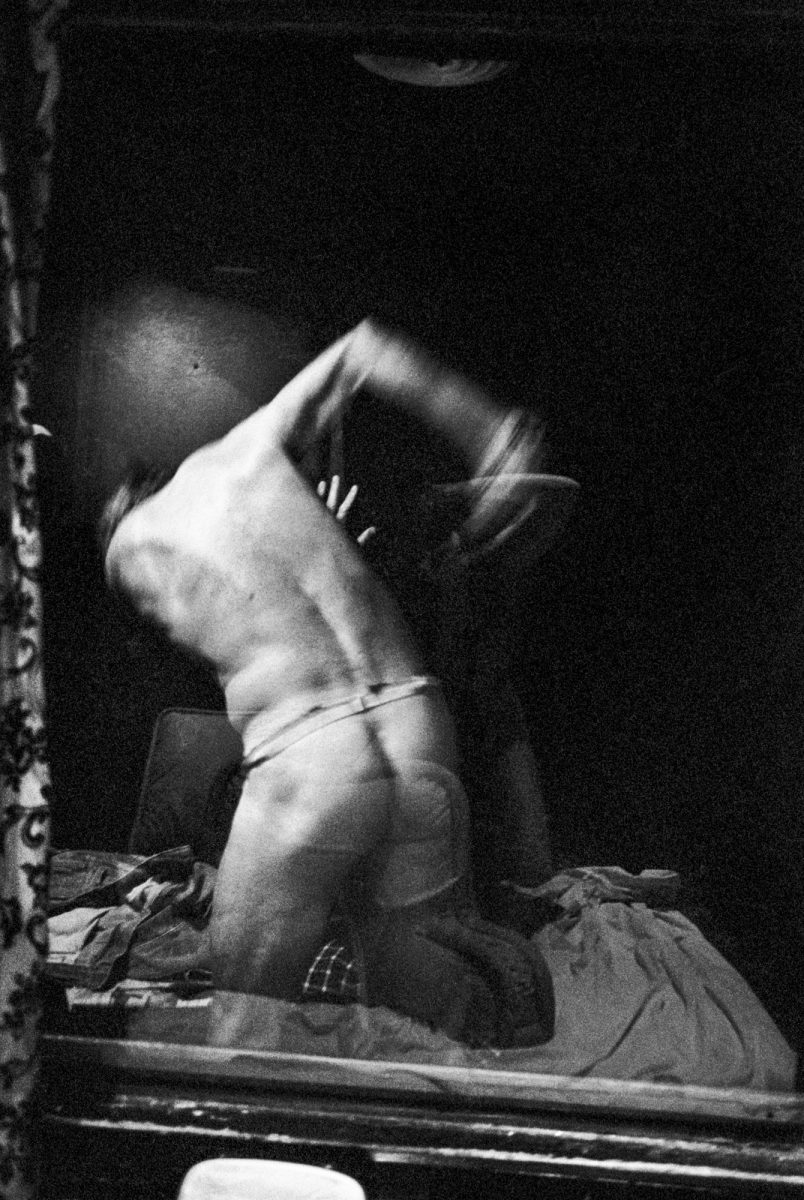

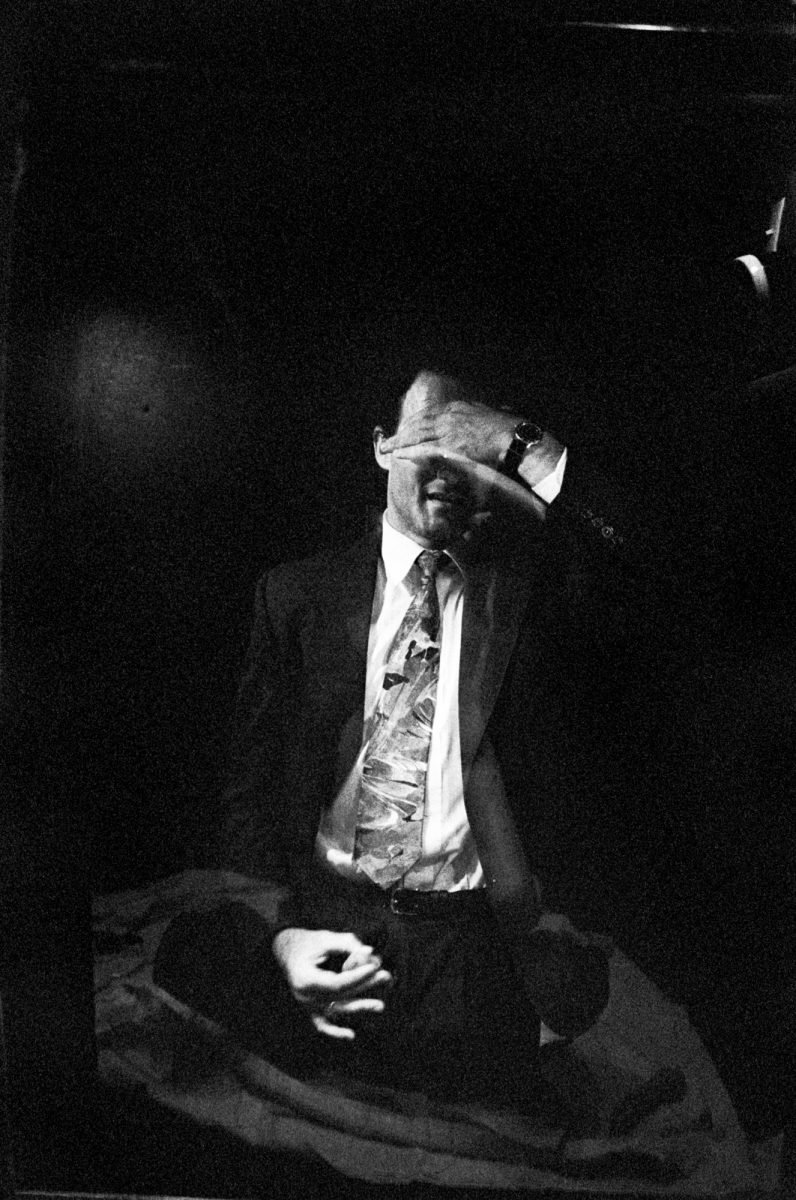

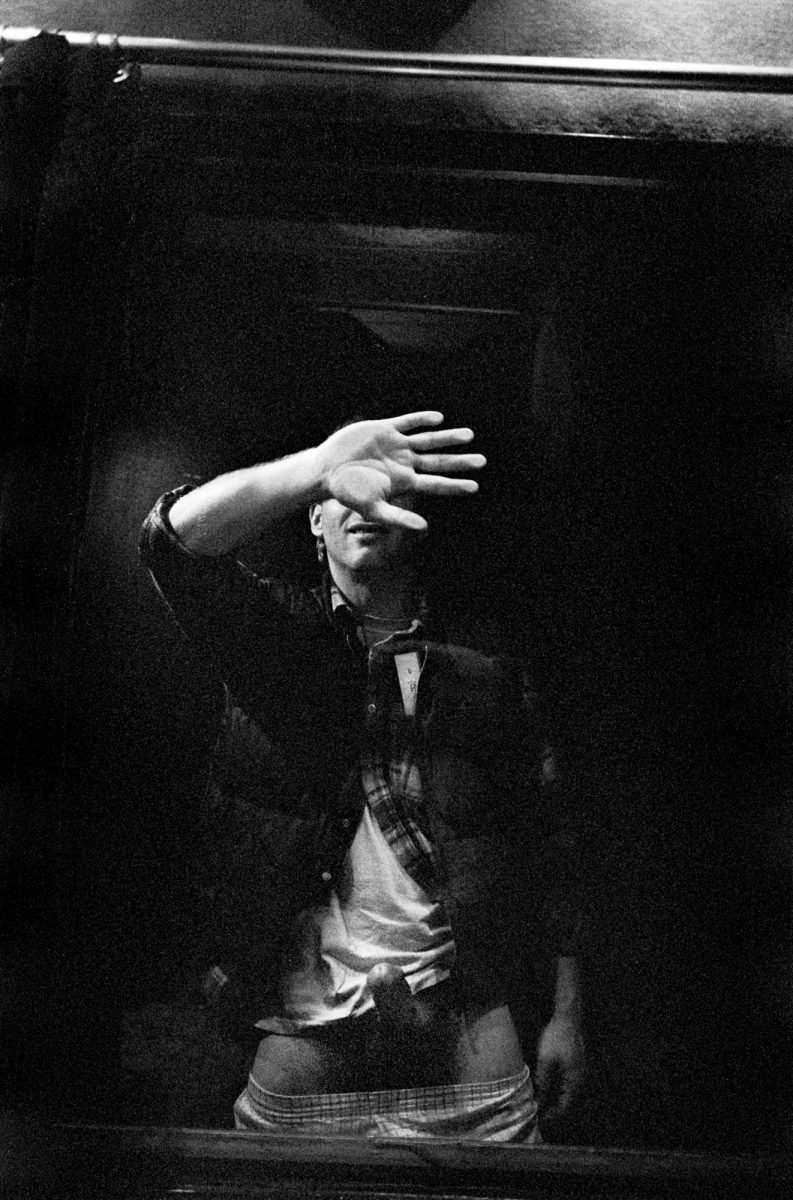

She offered her customers a free show for a portrait and, if they agreed, asked them to present themselves as they wanted. Some covered their face but others didn’t; some were clothed, others were naked or half dressed. Many had erections, some barely discernible but some obvious or even proudly displayed; other customers revealed more esoteric desires, pulling open their behinds, whipping themselves, or showing off women’s lingerie.

“What is most striking about this book is its insistence on Toloui’s perspective. She refused to become a cipher”

Toloui welcomed all sexual preferences except customers who wanted to be dominated or to abuse her. The former because she wasn’t good at it, the latter because it didn’t feel worth the money.

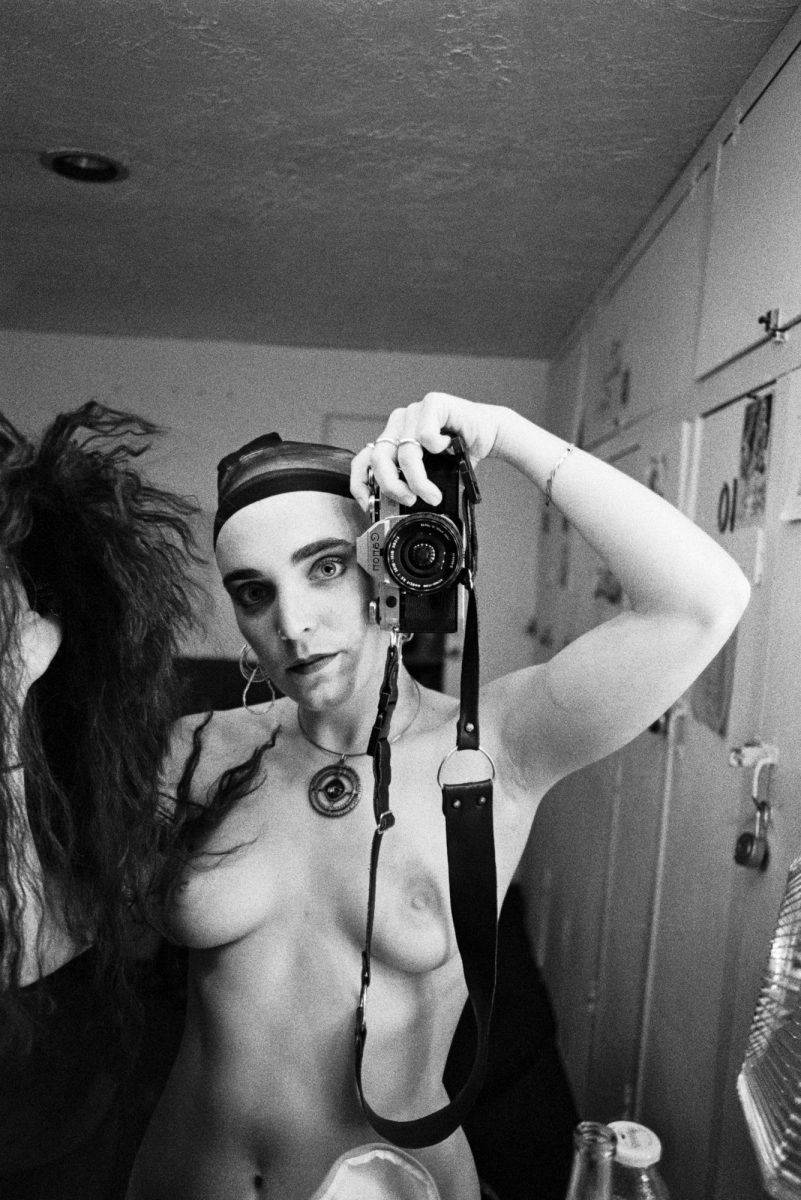

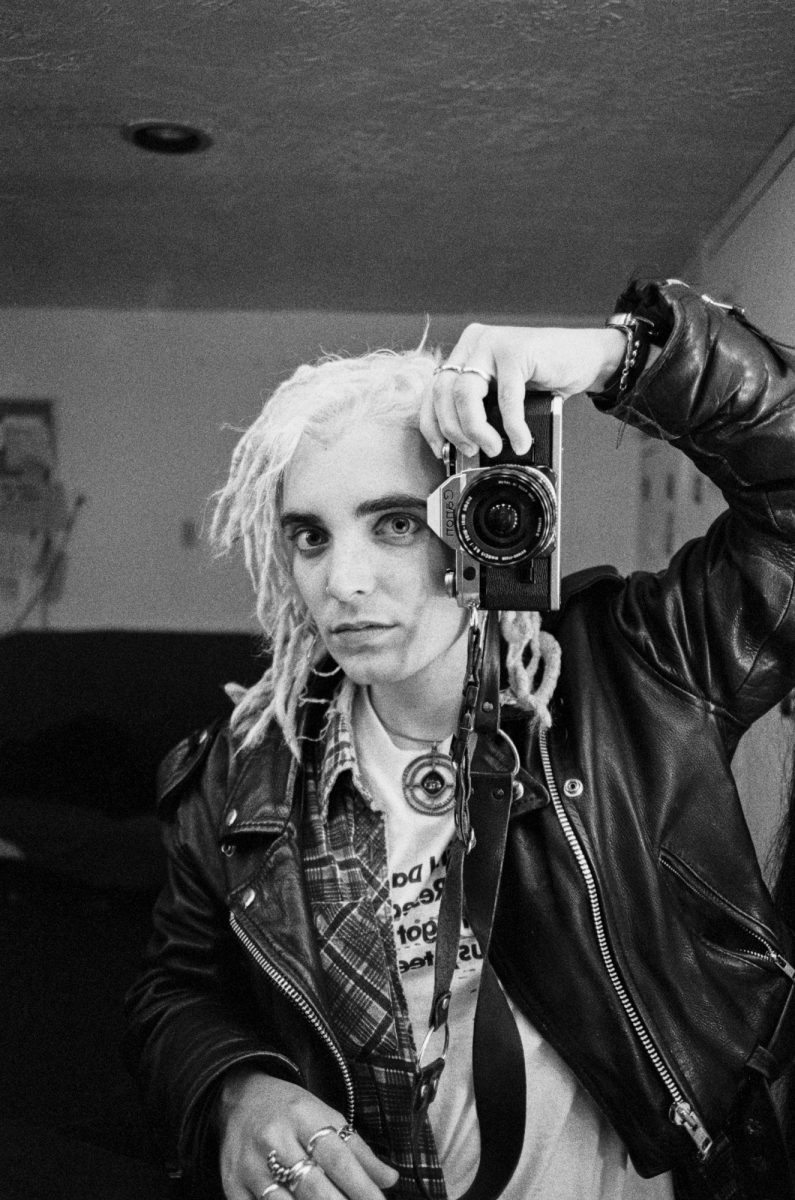

Continuing the project for two and a half years, Toloui managed to shoot around 100 portraits, 65 of which have now been published in a photobook, 5 Dollars for 3 Minutes. The book includes a lively text by Toloui, recounting her experiences at the Lusty Lady, as well as background shots, such as the peep show stage in action, or Toloui in the booth, transforming from a blonde-dreadlocked punk to long-haired stripper.

She wore a wig and worked under an assumed name, subsuming her identity into a generally acceptable vision of femininity. She also buried her own desires, because she wasn’t sexually aroused by the work. Some dancers were, she says, but even they didn’t love it for six hours a shift, three shifts a week, all lasting late into the night. The Lusty Ladies were there for the money, whatever the theatre’s name implied.

“Toloui not only looked straight back at the audience, she valued her view enough to record it”

What is most striking about this book, even 30 years later, is its insistence on Toloui’s perspective. She refused to become simply a cipher for (mostly) male desire: she allowed herself to be objectified, but subverted that objectification. Toloui not only looked straight back at the audience, she valued her view enough to record it.

As she points out, that wasn’t just unusual in the strip club. Women were (and still are) over-represented as subjects in art, and under-represented as artists. The male gaze dominates everywhere. Including photography, particularly in images around sex, whether they’re classified as art or journalism. There’s a parallel to be drawn between camera shutters and the peep show’s moving screens, between lenses and the customers’ windows.

But Toloui’s project doesn’t just say something about patriarchy. It speaks of a particular view of the world, a proprietorial attitude which critics such as Ariella Azoulay link with capitalism and outright imperialism. Images were once used to take stock of colonial subjects and territories, suggesting these subjects were stock or objects, goods that could be bought or sold.

By photographing her customers, Toloui turned the table, reversing the gaze, voicing her point of view and disrupting her status as object.

Diane Smyth is a freelance writer, curator and photofinder