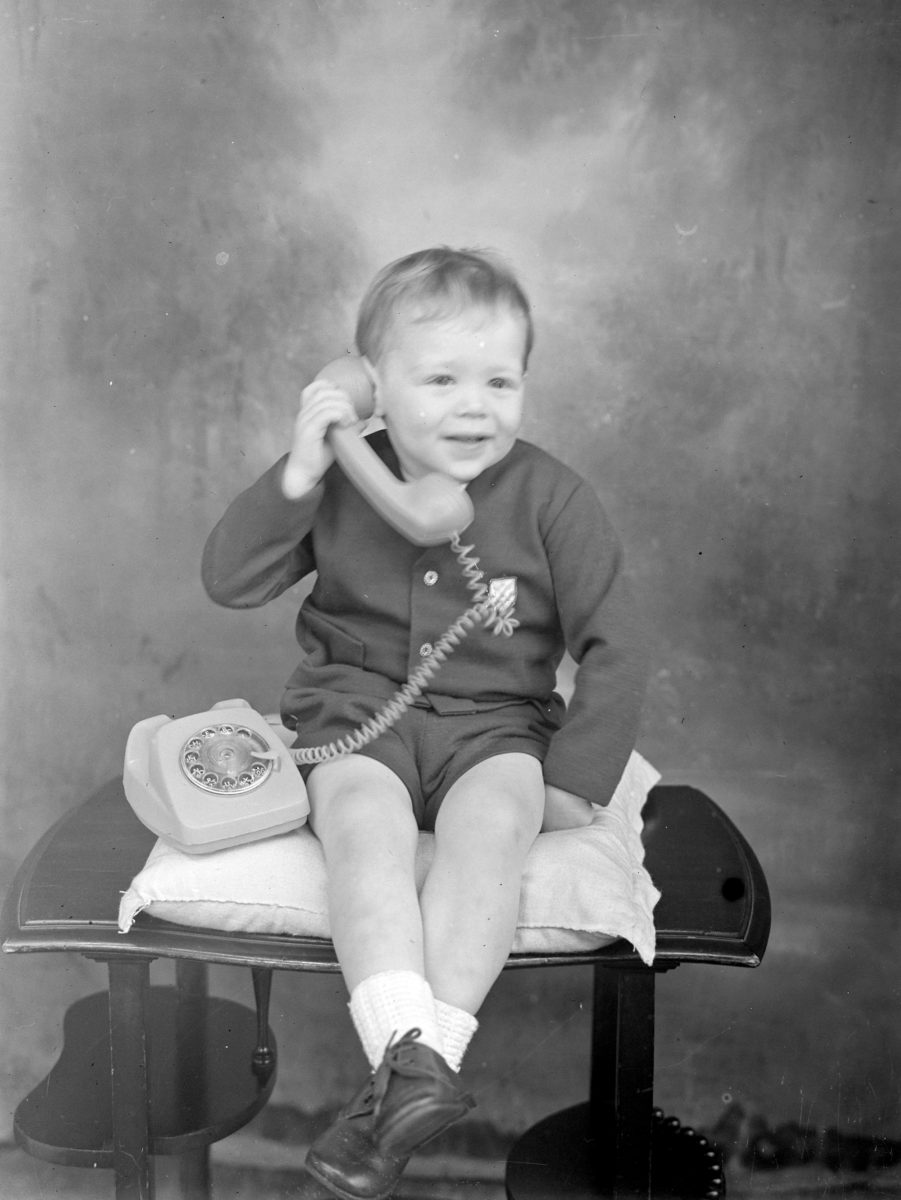

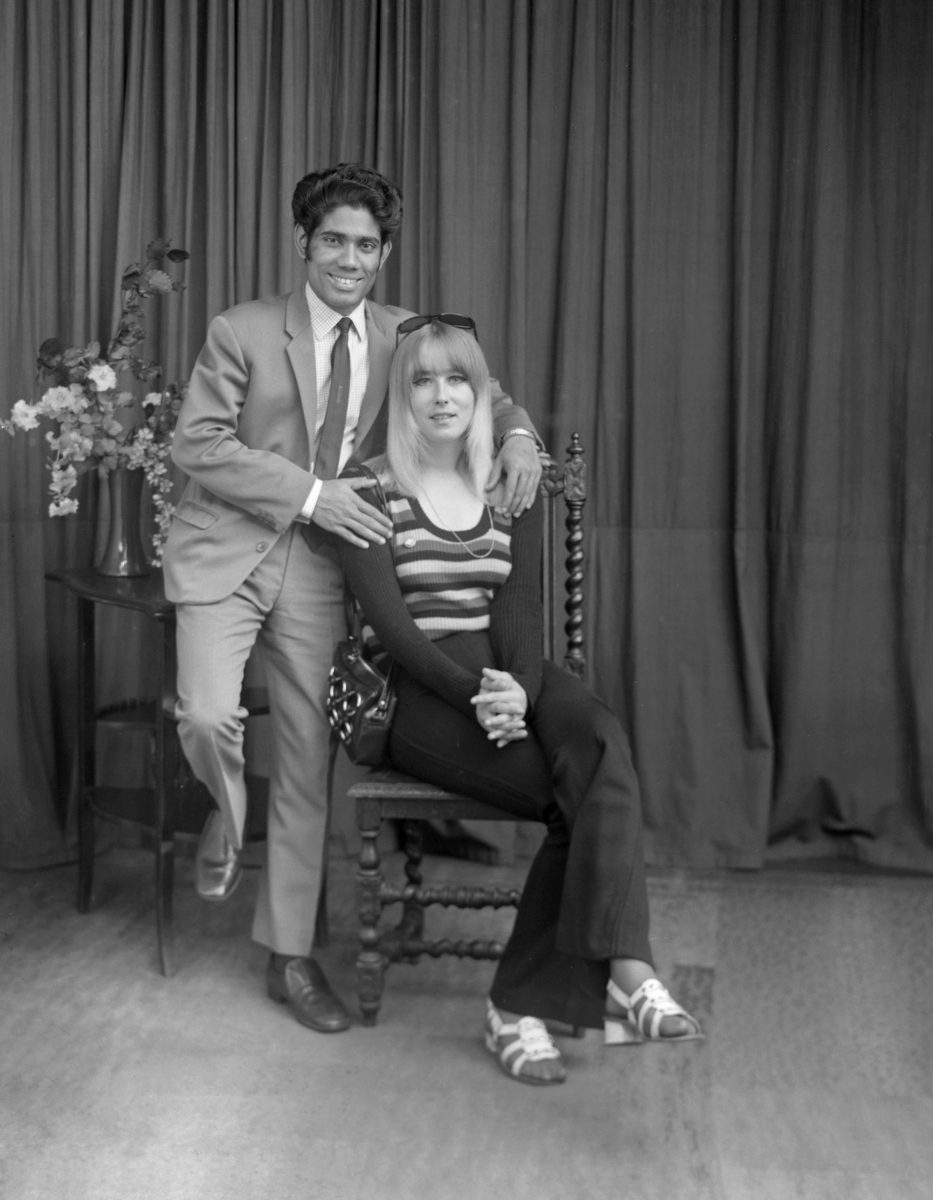

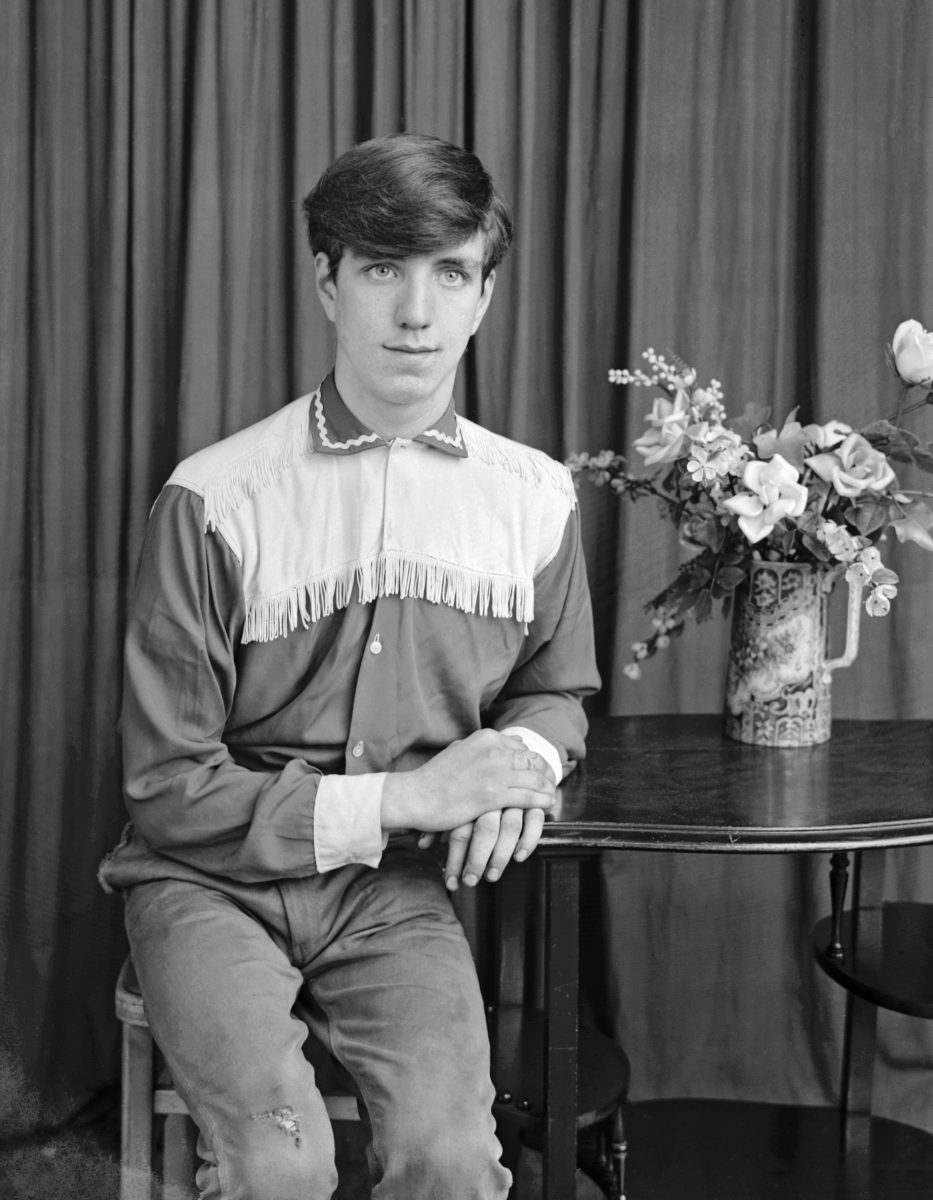

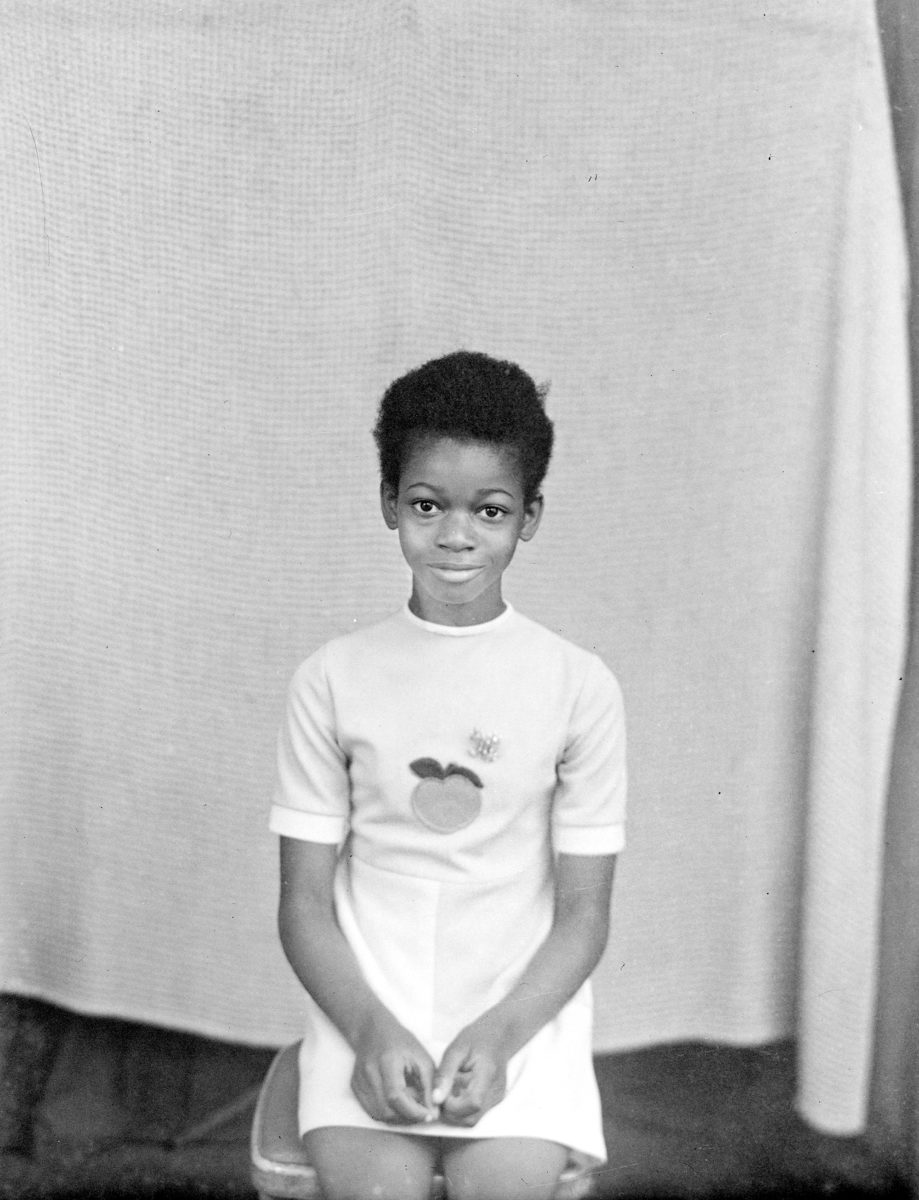

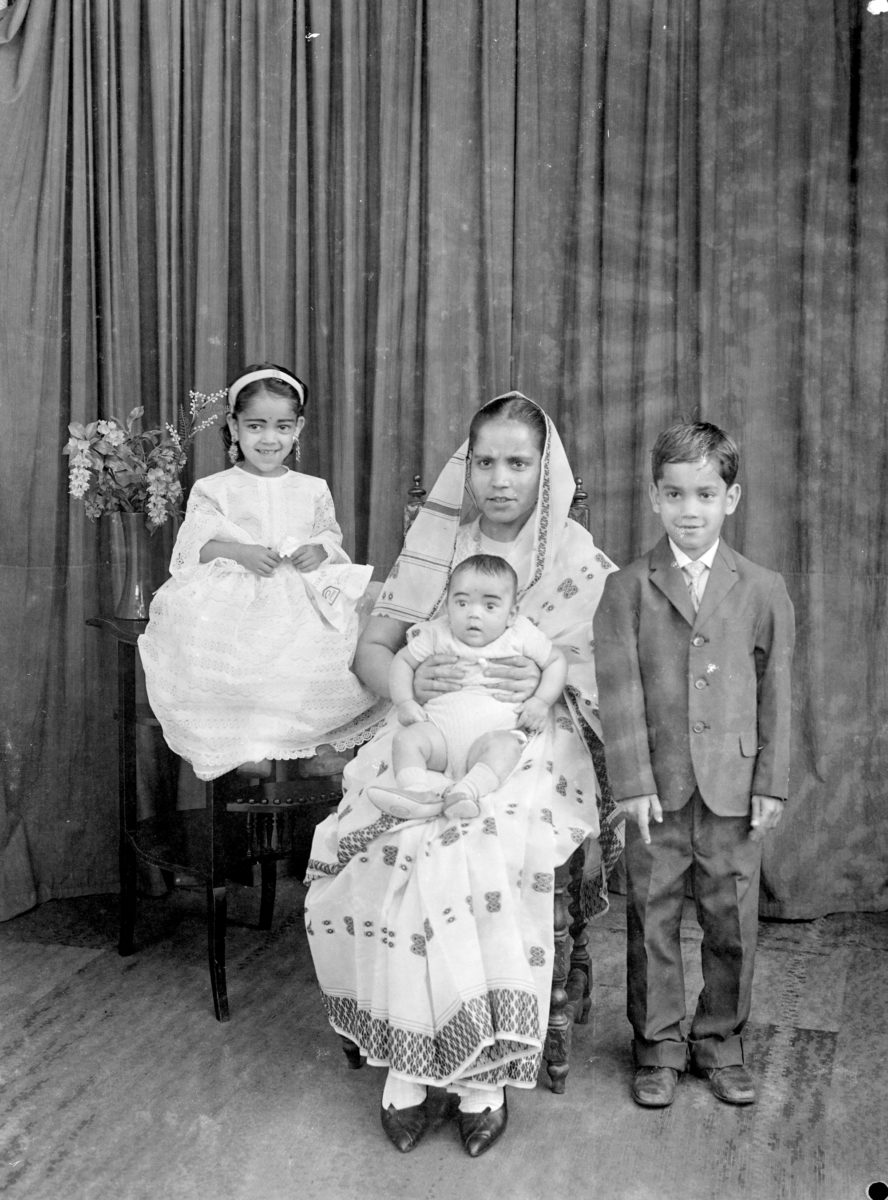

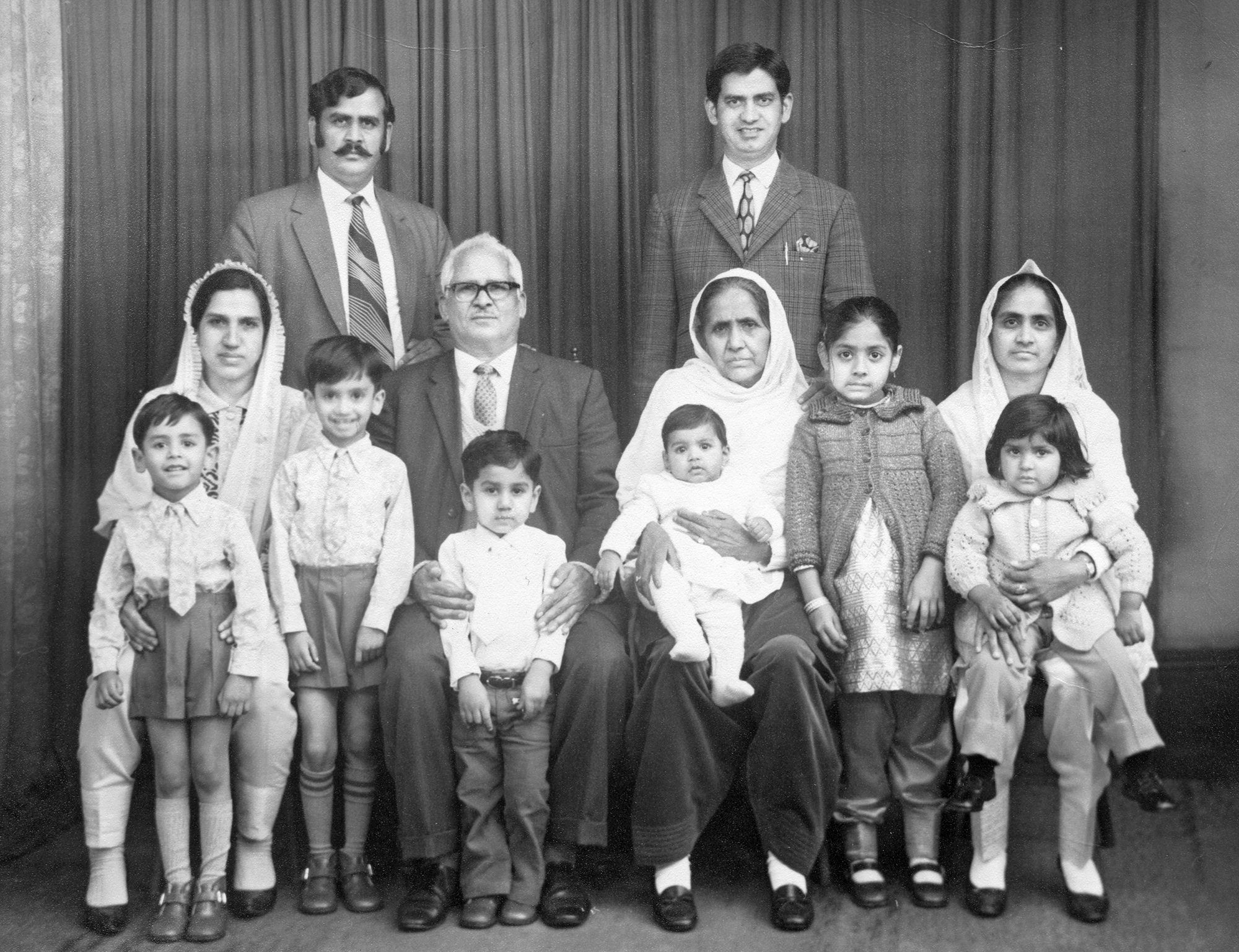

For much of the twentieth Century, one camera in the corner of a photography studio bore witness to the immense cosmopolitan evolution of Bradford, a city in the North of England. In the early nineteenth century, Bradford changed from a rural town bordered by woodland to a sprawling city by 1897, lavished with Victorian architecture. The city was named “wool capital of the world” and accelerated industrial growth spurred on post-war migration from much of the Commonwealth.

First opened in 1902 by Benjamin Sandford Taylor, the Belle Vue Photographic Studio captured professional portraits documenting the length and breadth of the city’s population. When Sandford Taylor retired, his assistant Tony Walker took over, but as access to cheap cameras proliferated, traditional portrait photography fell out of vogue, and the studio was forced to close in the mid 1970s. As Walker was clearing out his belongings, the new owner of the space stopped by and saw him throwing glass negatives into a skip. Upon closer inspection, he realised the significance of the 17,000 negatives Walker had in his possession, and insisted on rescuing them. They now are part of the Bradford Photo Archives, who are involved in an ongoing journey to locate the subjects of the photographs.

Today, the images make for nostalgic viewing, a window into the rise of Bradford from a pre-war homogenous city to an industrial powerhouse, flooded with cultural fusion. Tony Walker maintained many of the traditional Victorian methods, such as utilising natural light, older plate cameras and placing subjects in formal poses. Although this style became increasingly unfashionable over the years, it was highly desirable for those who emigrated to Bradford at the end of the 50s and early 1960s. Hailing from Eastern Europe, the Caribbean and South Asia, many immigrants coveted photographs of themselves to send home to families. For them, these images were evidence that they’d begun to prosper, and that the long journey was worth the risk. Walker built his business off newly arrived immigrants, and no one was turned away.

A BBC documentary was filmed in 2019, charting Bradford native Shanar Gulzar’s journey to track down the people in the portraits. The film shows the emotional reckoning her interviewees undergo when recognising family, friends or even themselves in the photographs. Often, the subjects had few other photos taken of them, so stumbling across these hidden gems evoked long-forgotten memories. Many of those interviewed speak of an immigrant community spirit, one where families worked hard to buy homes big enough to be able to house other new arrivals, in order to pass on the generosity extended to them when they first set foot in the city. Although racism was rife, the tide of migration was constant enough to ensure community existed as a comfort to those who were separated from family.

Portraits were a time for people to dress up in their finery—the photographer would add props, or ask subjects to pose at particular angles, emulating Victorian-style paintings or film posters of the day. The 50s and 60s made portraits accessible to those who wanted to show off their prosperity. Today, in an age where documentation is constant, bordering on incessant, investing in portraits seems even more of a luxury. However, nowadays they are still popular with immigrant families, who are keen to depict themselves in the best light. The Belle Vue Studio portraits speak of a lost time, a slower culture where subjects had to pause for several moments to ensure their photos wouldn’t blur. As digital culture proliferates, will our selfies evoke the same nostalgic aesthetic for future generations to come?

All images courtesy of Bradford Museums & Galleries