The language of collage is one that is comfortingly familiar to many today. It feels both beautiful and strange, while being gloriously accessible. But that doesn’t undermine its power as a medium, and it has been readily adopted by advertising and hobbyist culture alike. Meanwhile, the enduring popularity of the collage as an art form is in no small part thanks to the work of John Stezaker.

A new show of his work at Luxembourg+Co. gallery in Mayfair, London, titled At the Edge of Pictures, examines his early work made from 1975-1990 through multiple lenses: the capacity of collage for subversion; the relevance of collage in the 1970s when the dominant ethos was around ripping things up and starting again; and the nature of the mechanical means in art-making.

“Where postcards usually make monumental sites into miniatures; film takes mundane things and makes them huge on the big screen”

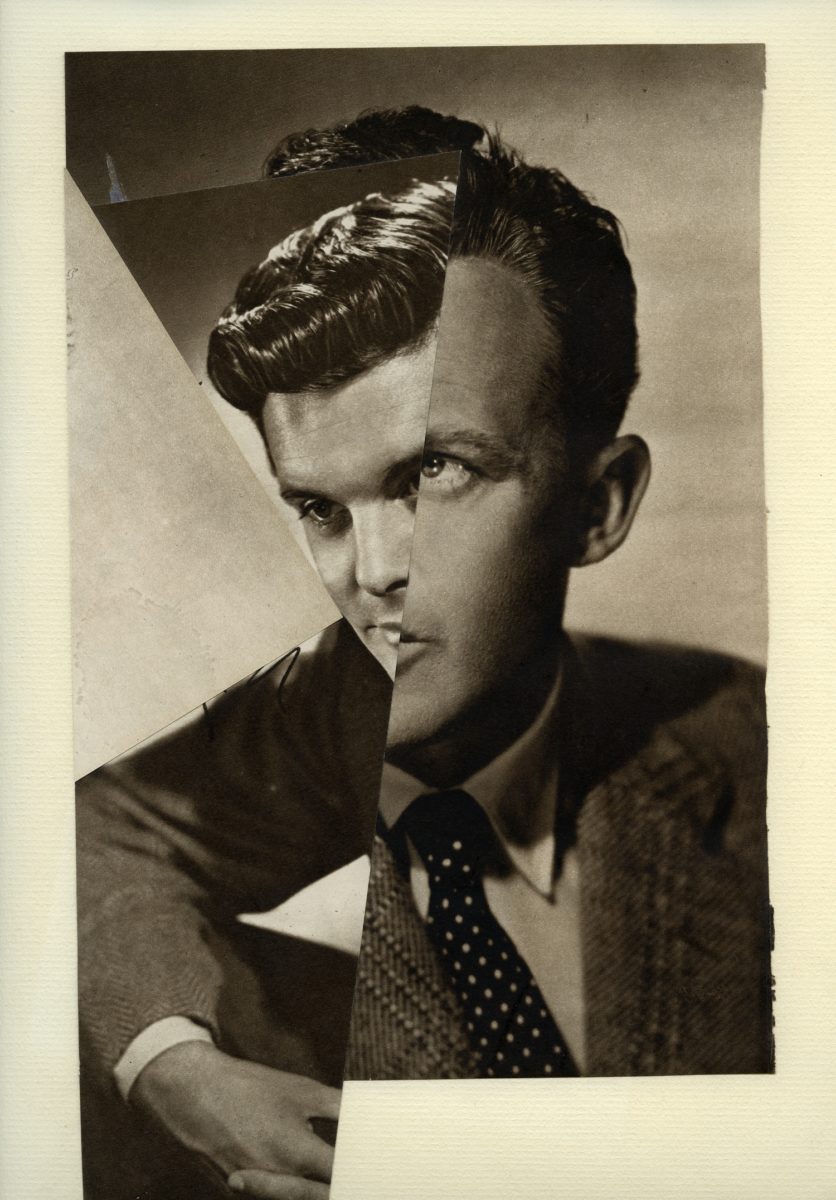

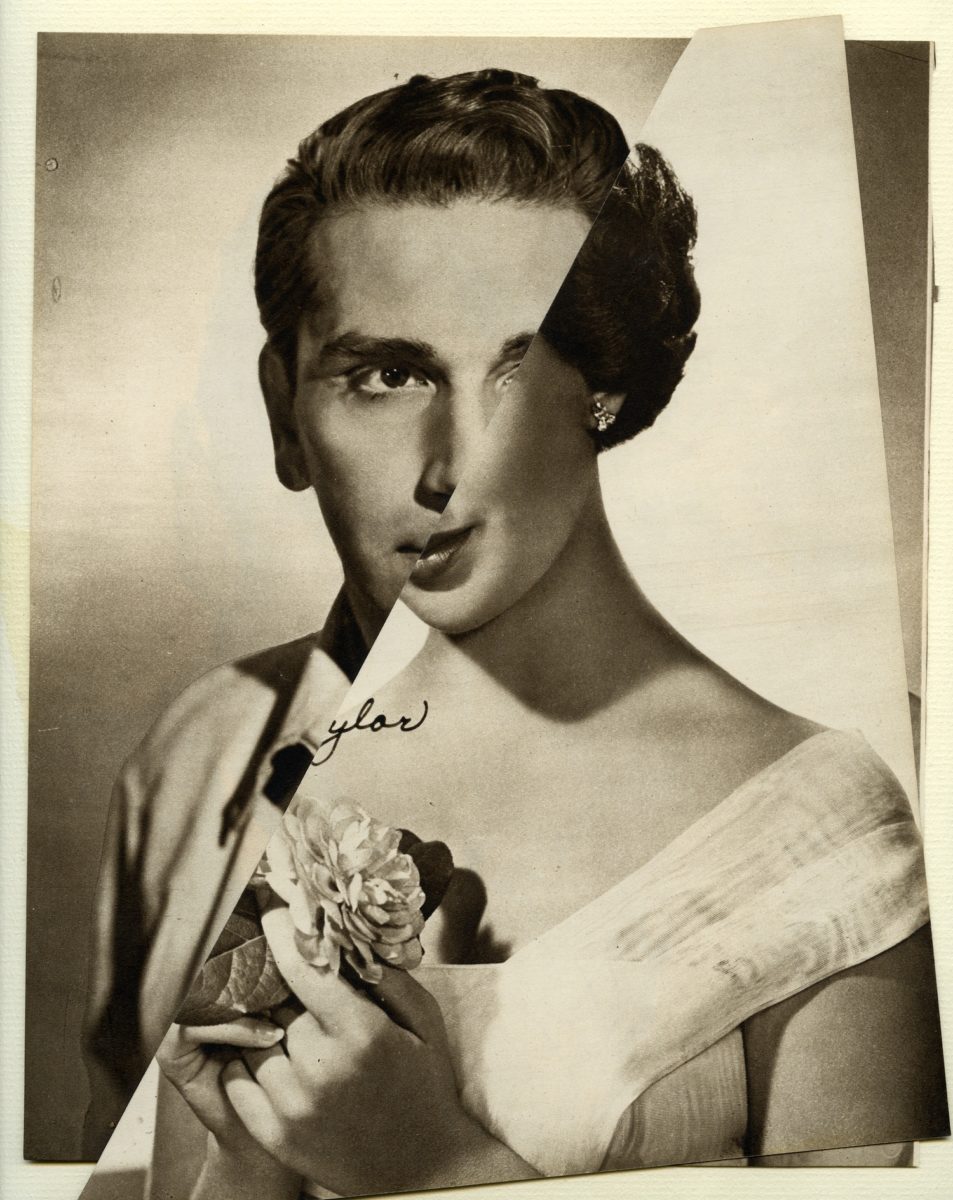

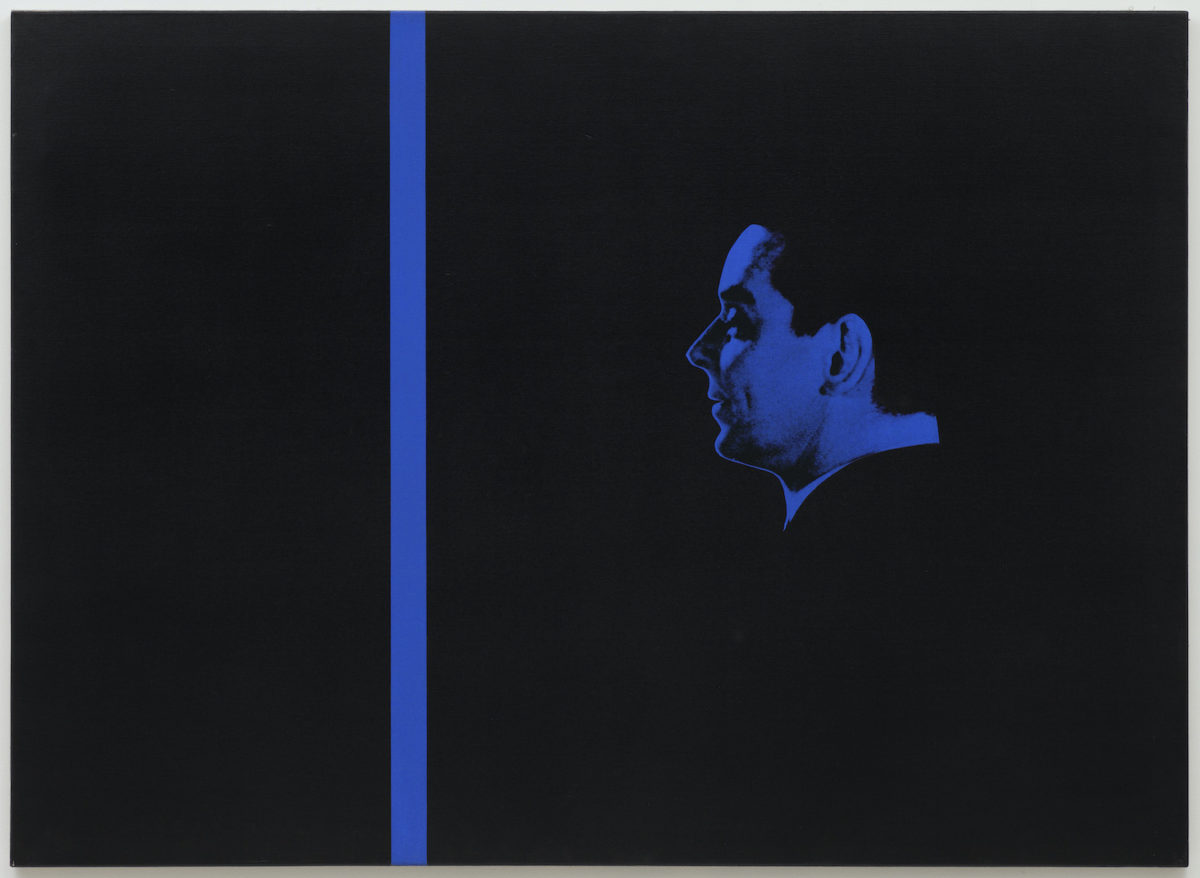

The exhibition coincides with the publication of a new monograph of Stezaker’s work, published by Koenig Books and authored by Dr. Yuval Etgar. Some of the most imposing and striking works on display are those that have never seen before, and this is one of the only occasions in which Stezaker’s more well-known works (such as the “Marriages” series, where two different portrait images are combined into one strange, borderline-grotesque face) are shown alongside his vast silkscreen pieces, which combine vivid bursts of coloured paint with mechanically printed images and collage processes.

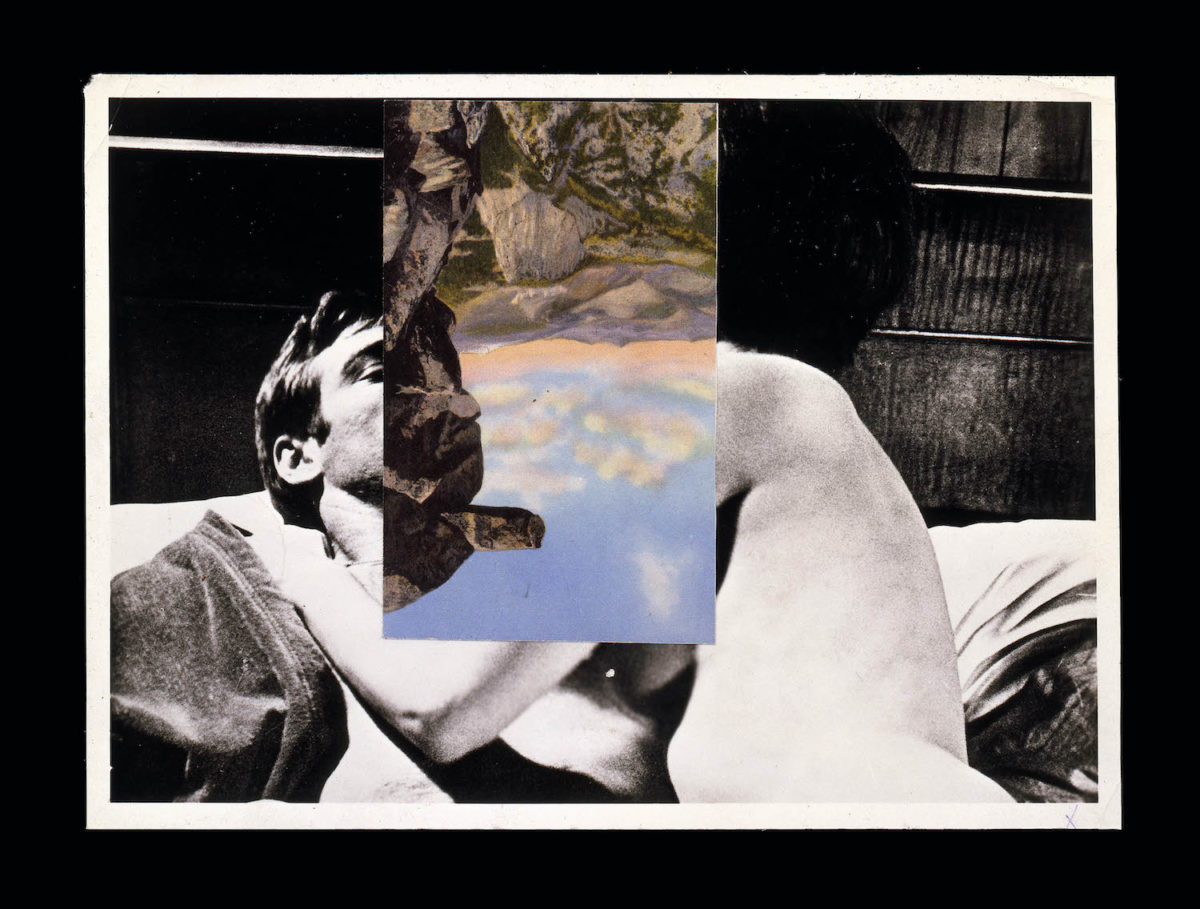

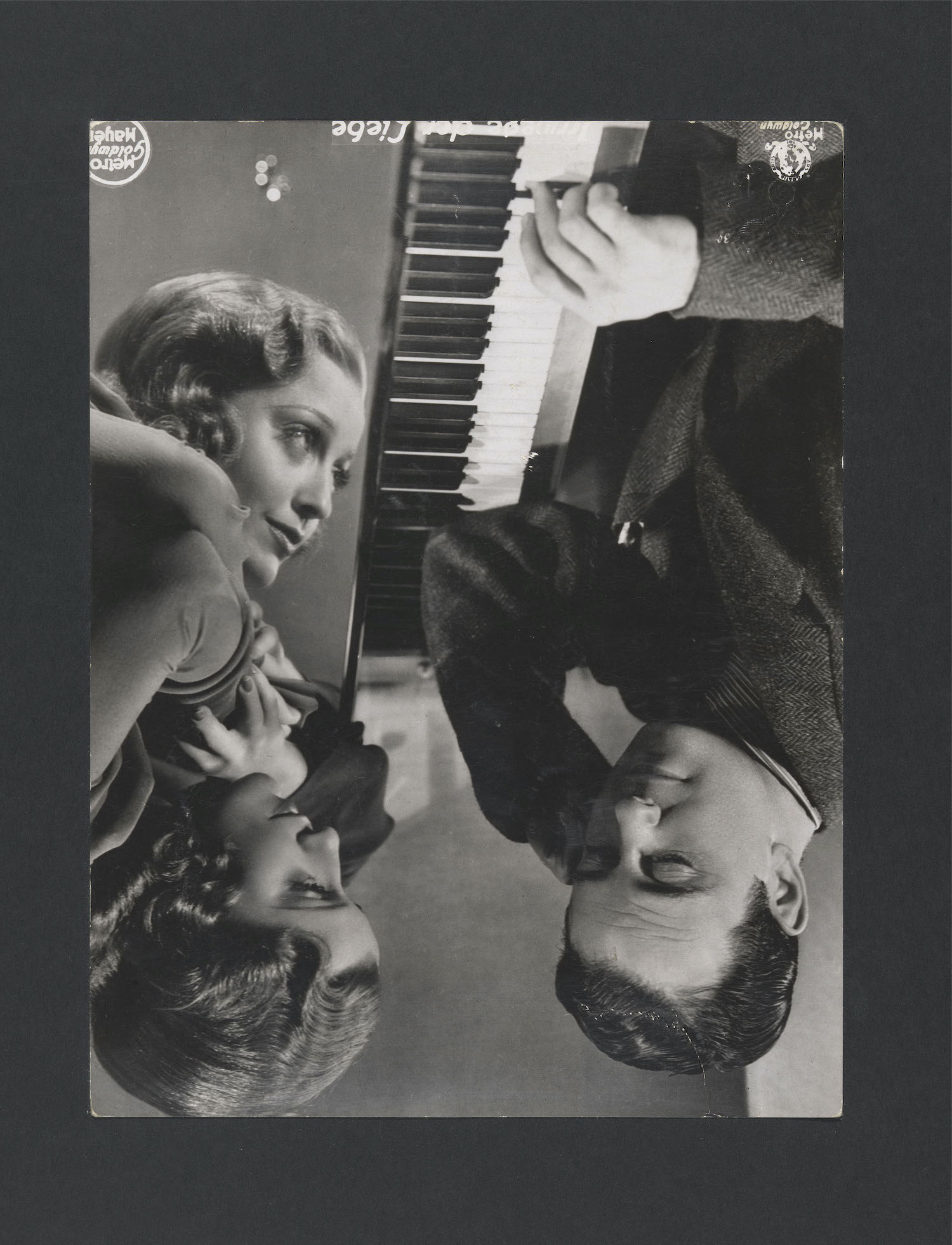

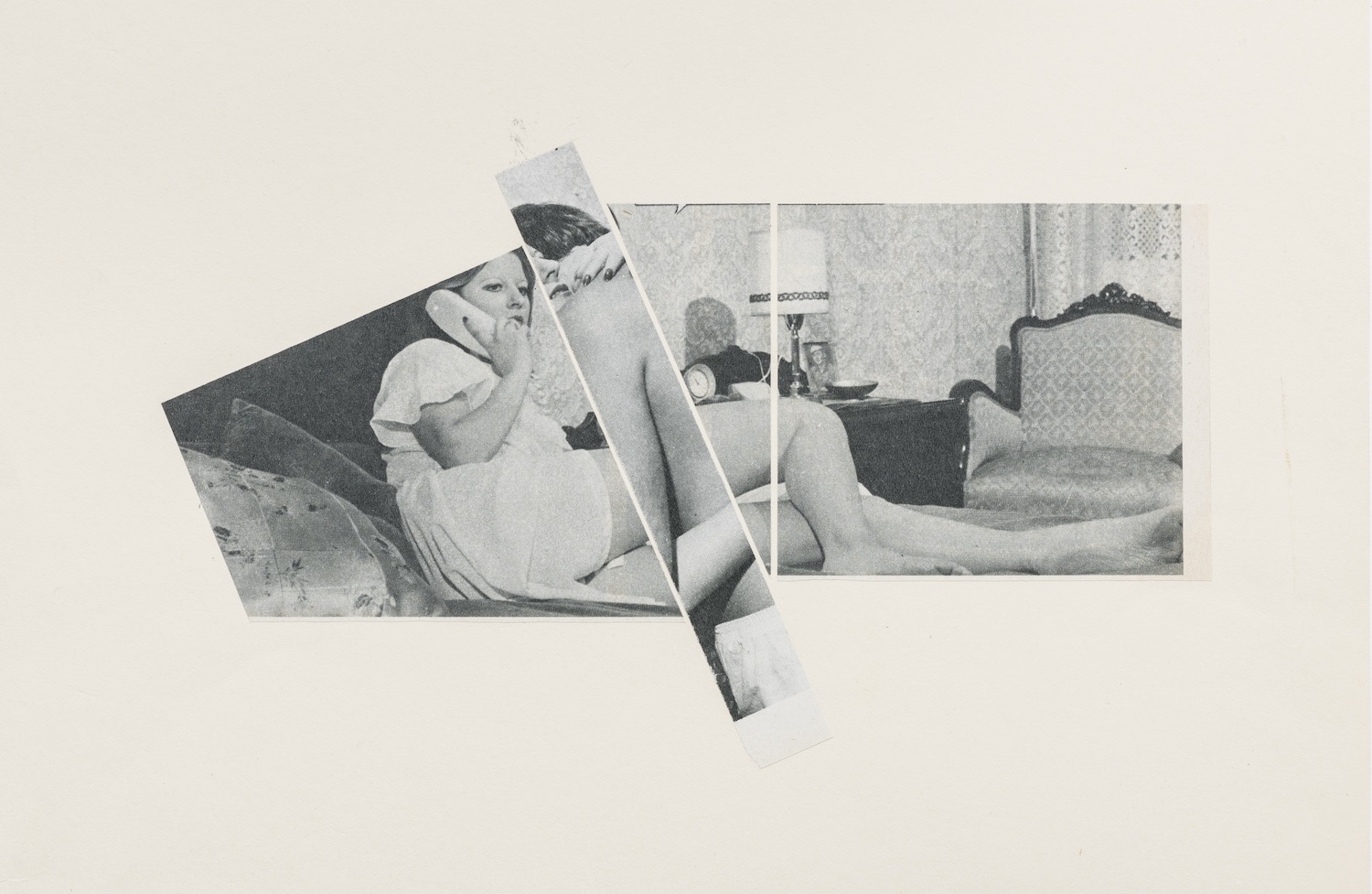

According to Etgar, these early works can be seen to show Stezaker “before he really finds his voice.” Many of them explore the idea of the “photoroman”—a kind of trashy magazine-based, melodramatic soap opera that was popular in many countries including Italy, Spain and those in Latin America during the post-war years and mid-twentieth century.

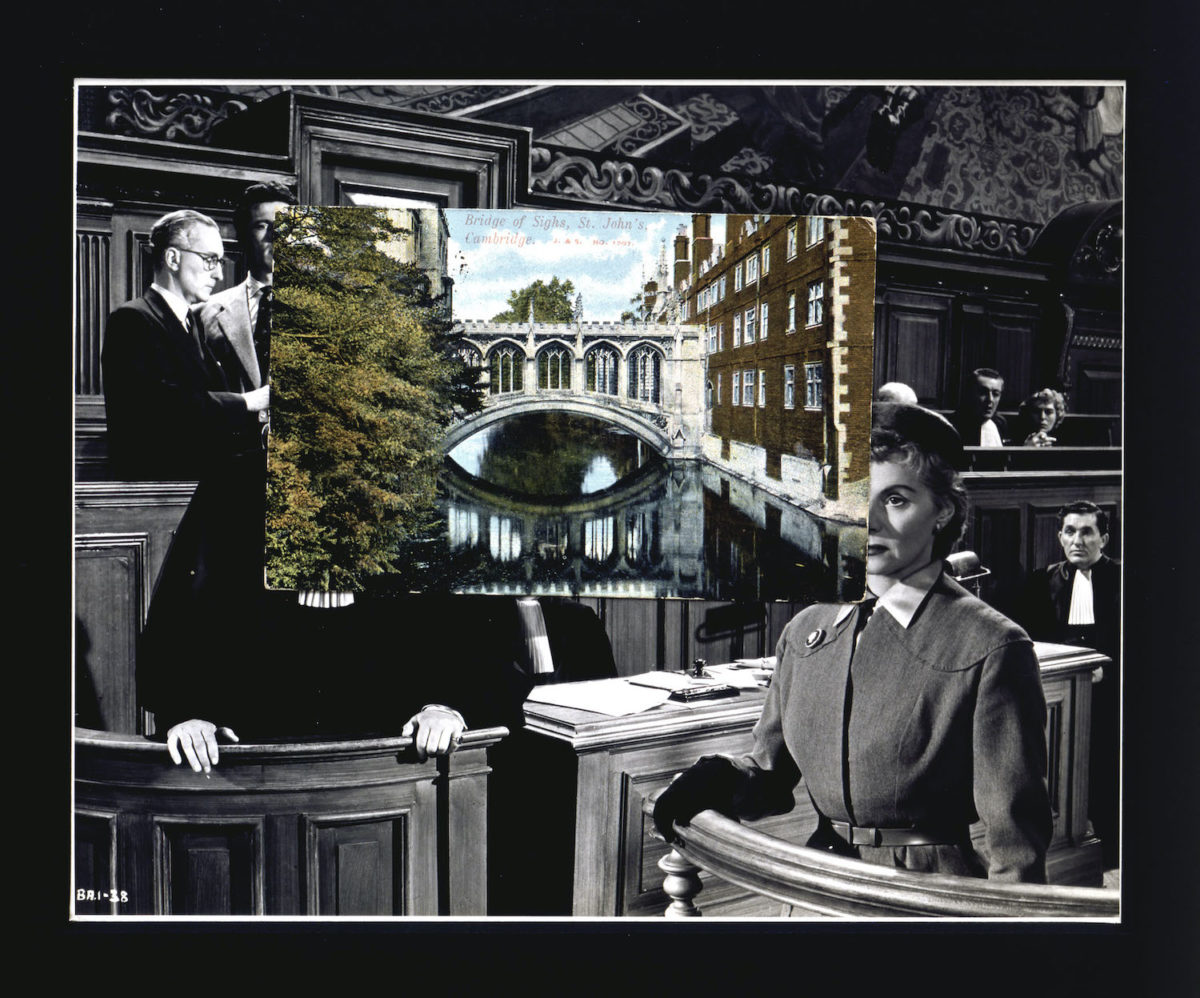

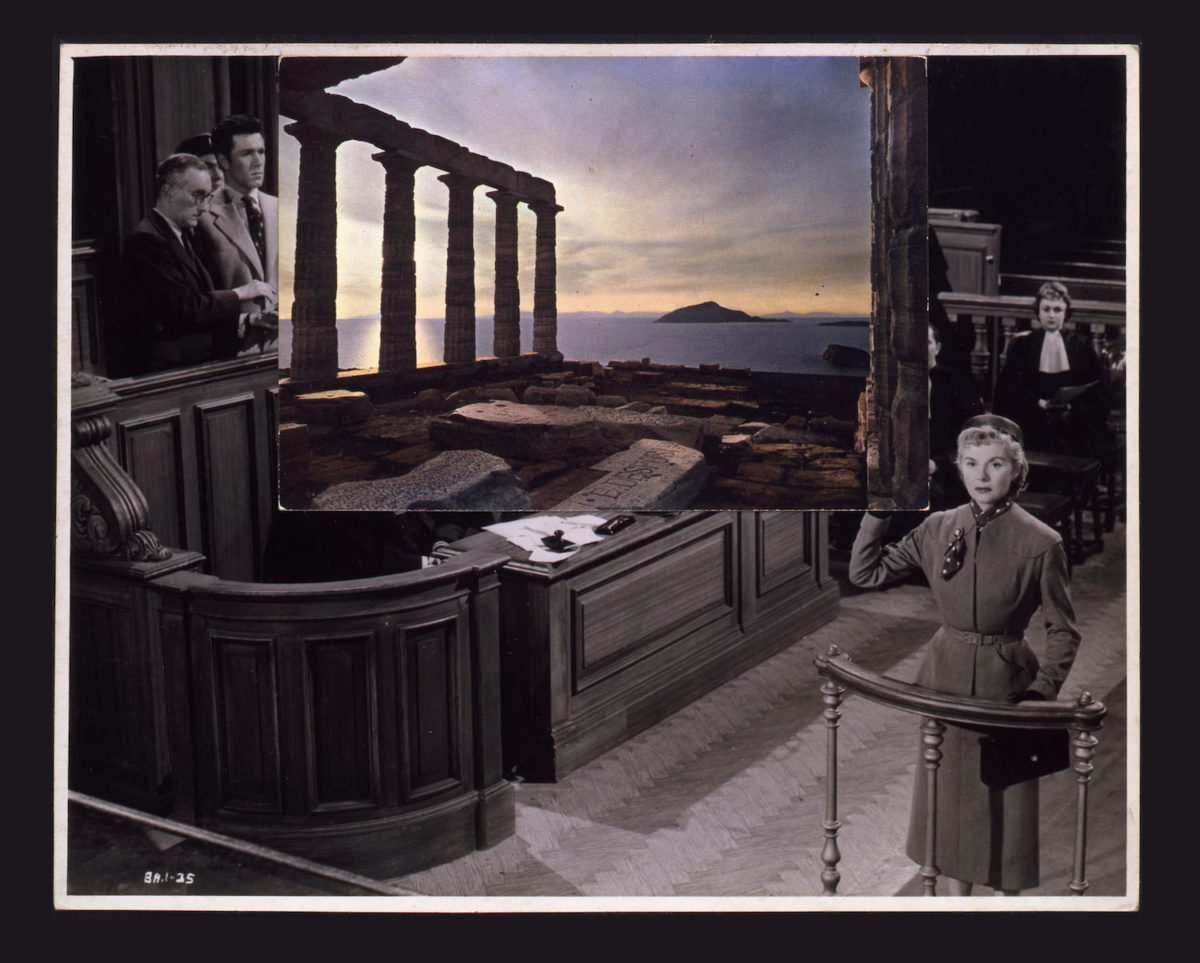

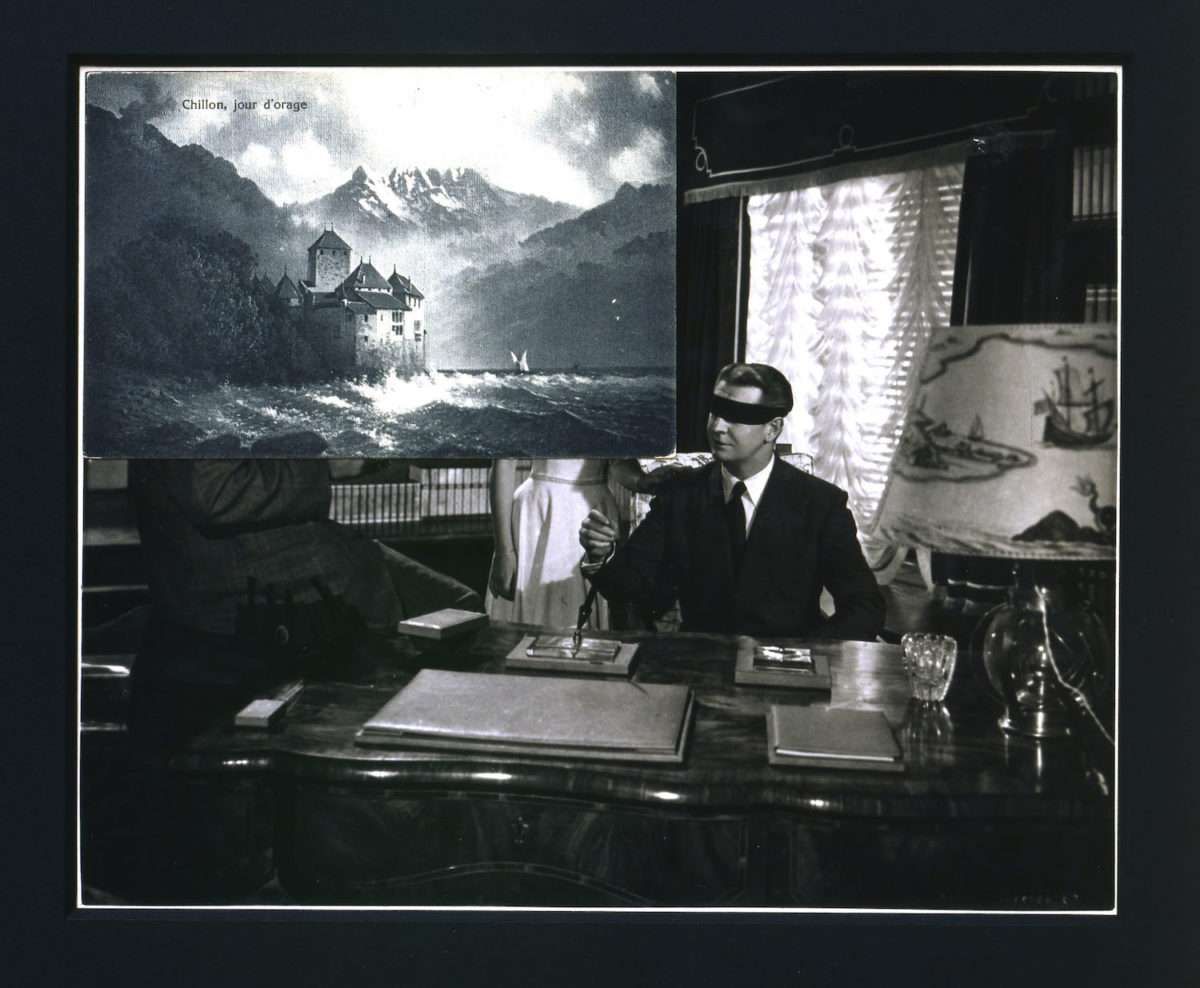

- John Stezaker, The Trial 1980; The Oath, 1978; Blind, 1979 (left to right)

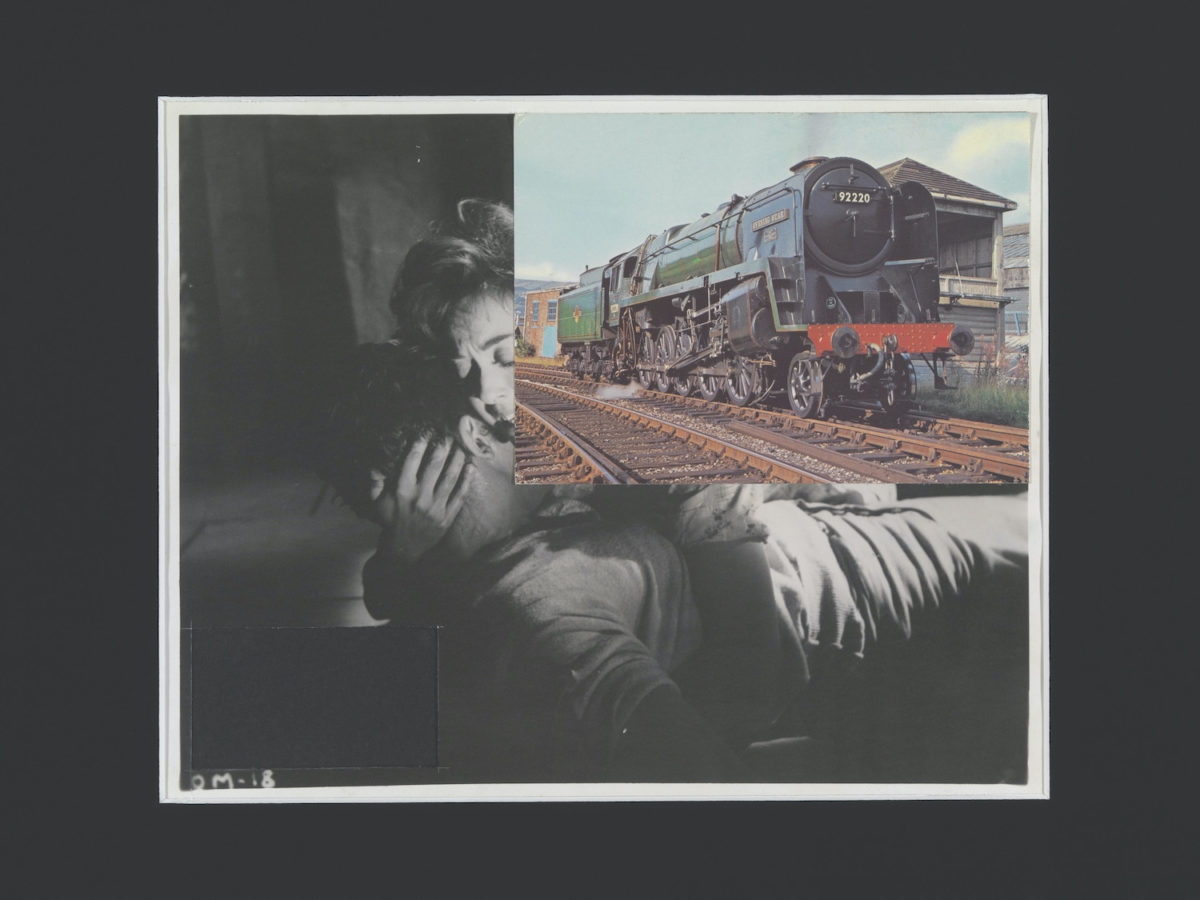

This playful approach to the dynamics of drama, and the interplay of outdoor and interior spaces (such as Stezaker’s combination of postcards showing vast landscapes with intimate film stills) carries throughout much of the artist’s work. As with all of his mark-making, the choice of postcards as a tool was no accident: according to Etgar, they “capture exactly what mechanical reproduction did to our way of looking at pictures.”

He continues: “A postcard takes these giant monumental places outdoors and compresses them into a tiny little thing with a million copies. So a million tourists would get the same image of the same place, but it’s such a personal experience when you add a little writing on the back.” He adds, “Where postcards usually make monumental sites into miniatures; film takes mundane things and makes them really huge on the big screen. John’s collages are all about this play of very small and very large.”

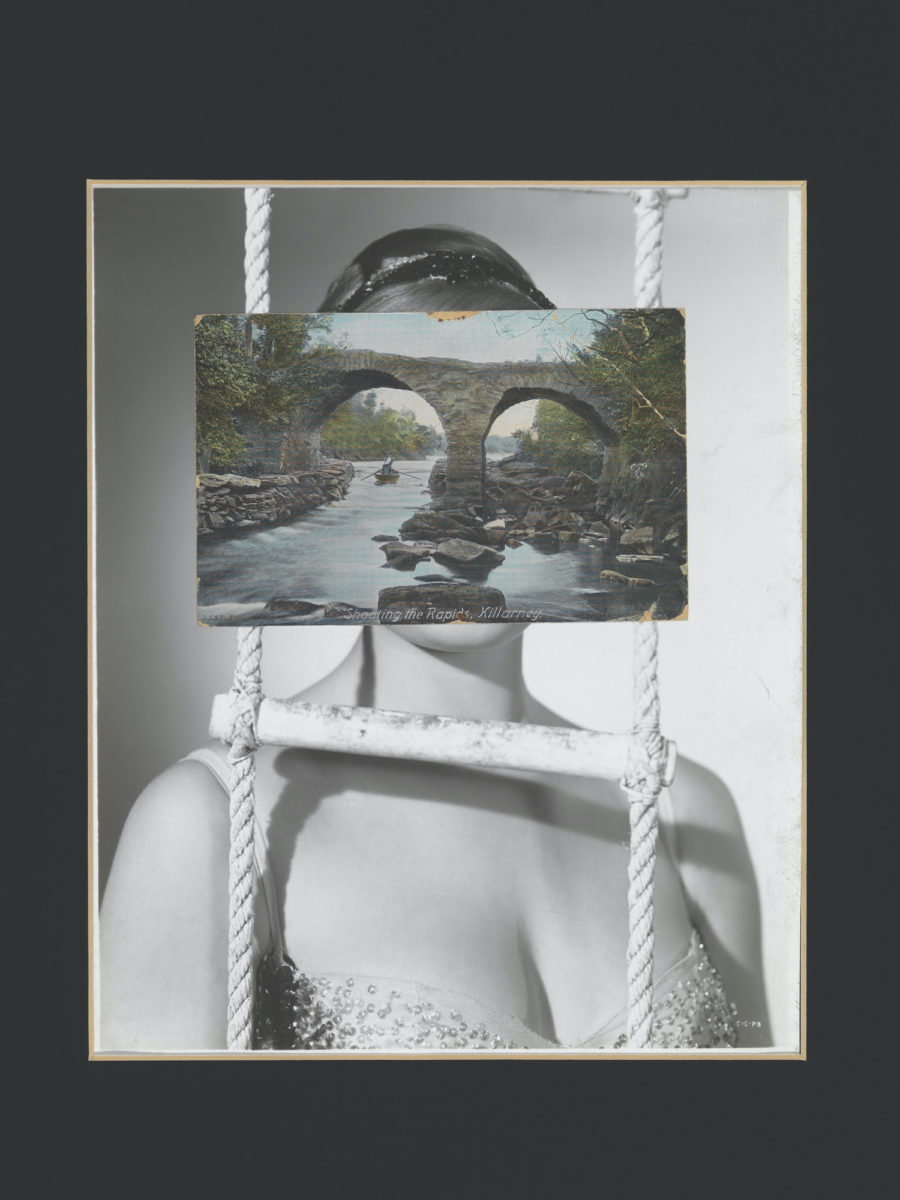

- John Stezaker, Untitled, 1979 (left and right)

Another key tenet of the work that comes to the fore in this exhibition is Stezaker’s fascination with the accumulation of images: it was in the twentieth century that the vast proliferation of pictures reached new heights, thanks to the widespread use of reproduction techniques and cheap printing technologies. While Stezaker’s collage contemporaries, such as Linder, took a very “punk” approach to the medium, Stezaker’s stance resolutely stood with then-unfashionable movements like Surrealism and Dadaism. It has cemented his reputation as a conceptual artist: his work seems to have far more in common with the likes of Kurt Schwitters and Man Ray than snarling 1970s punk-nihilism.

Etgar posits that Stezaker’s work, in this way, is as much a theoretical accomplishment as an aesthetic one; especially when you consider that many of the works hail from 1977—a time where ideas around technological or digital advances were becoming far more popular (not least thanks to the release of the first Star Wars film). The work, in many ways, is about “the idea of looking at things not as carriers of information or narrative but abstract, and then doing that with images,” says Etgar.

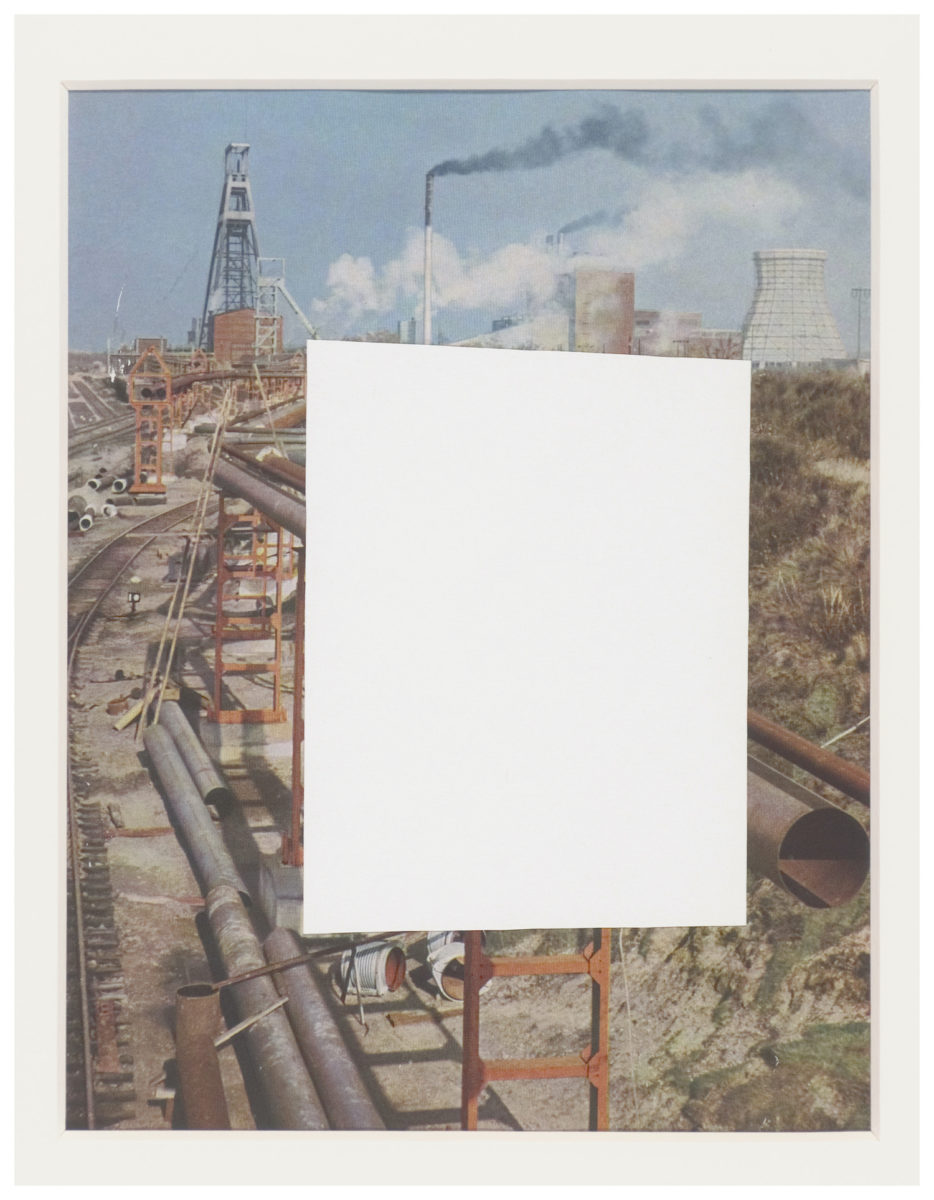

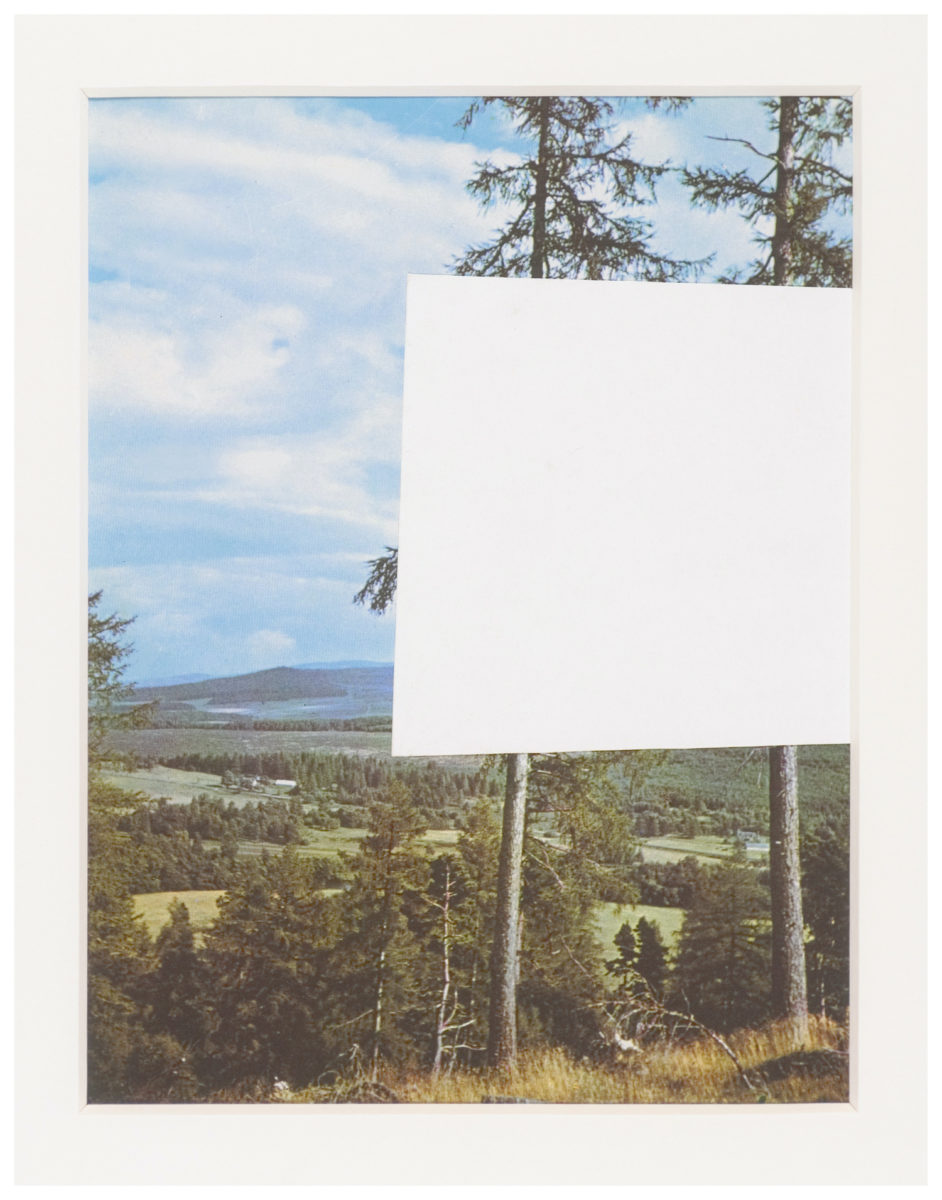

- John Steazaker, Tabula Rasa IV, 1990 and Tabula Rasa III, 1990 (left and right)

“Part of what makes Stezaker’s work so endlessly compelling is the stories that we can’t help but subconsciously form to fill in the gaps”

That idea of abstraction, and of moving away from images as narrative vessels, however, can feel antithetical to human nature. Part of what makes Stezaker’s work so endlessly compelling is the stories that we can’t help but subconsciously form to fill in the gaps. Works in his Inserts series from the 80s use a screen that seems to float both in front of and behind the images.

Etgar sums up this merging of narrative and abstract in Stezaker’s work: “He likes to play with connections… His work can be so full of narrative and images and people and details, but the idea is hopefully to create this jarring effect that enables you also to forget details, and not to be able to solve the story that’s happening in there. The story is of the disruption.” And that story, as the show title so nearly summarises, occurs at the very edge of the pictures.

At the Edge of Pictures: John Stezaker, Works 1975-1990

2 October-5 December 2020, Luxembourg + Co.

VISIT WEBSITE