Attending to pornography, as real, as representation, as art or cinema, as political and philosophical, is incredibly complex. Can porn ever really provide a sense of agency, both to those working on its sets and to those watching, and a method to fuck with the sexualising and racialising gaze? Or are the ethics of porn simply written on the wall, a flickering, waning reflection of the politics of bad sex?

Amia Srinivasan’s new book The Right to Sex

grapples with how the ways we have sex are always political, and how porn continues to produce some of the most crucial questions for feminist thought. In the second chapter, ‘Talking to My Students About Porn’, the Oxford social and political theory professor opens up a discussion with her students about straight mainstream porn, asking “Is it a tool of patriarchy or a counter to sexual repression? A technique of subordination or an exercise of free speech?”

Srinivasan assumes that for her Gen Z students discussions about porn are “prudish and passé”, yet her assumptions are quickly upturned. To her question of whether “pornography doesn’t merely depict the subordination of women, but actually makes it real”, her students respond with a resounding yes.

It feels particularly striking that Srinivasan principally builds her argument upon second-wave feminists such as Catharine A Mackinnon and Andrea Dworkin, who, in more contemporary feminisms, are often readily challenged and rebuffed. One of the reasons she gives for her students’ recapitulation of the second-wave takes on porn is that they are the first generation truly to be “raised on internet pornography”, by which she means “ubiquitous, instantaneously available porn”.

Srinivasan suggests that the children of the internet have had their desires precluded by porn, the script has already been written. But does this not suggest that porn is an a priori script for sex and pleasure when, in fact, hasn’t heterosexual sex always, also been scripted and written by the nuclear family, public sentimental life, art and politics, too?

While Srinivasan is clear she is talking about mainstream straight porn, does thinking about other genres of porn complicate our understandings of it? Or, as Mark Fisher writes, might the question be “not, then, whether pornography, but which pornography?” There are countless examples of porn that blurs the boundaries between art, photography, cinematography, sex and everyday life, and how these intervene in the politics of porn’s representations.

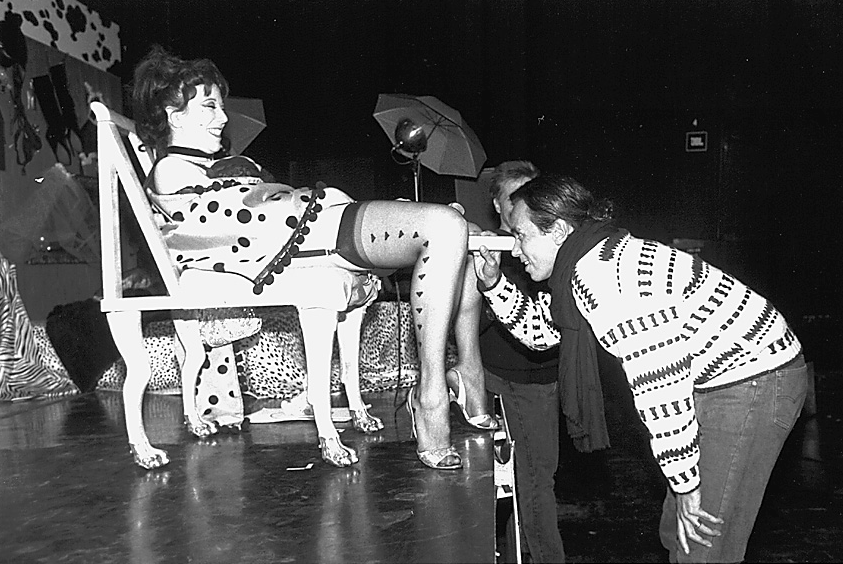

In 1990, ecosexual, former “prostitute-performance artist” Annie Sprinkle staged a performance entitled Post–Porn Modernism at The Kitchen in New York. Spectators stood in line waiting to shine a flashlight through the speculum she had inserted into her vagina, what Sprinkle called a ‘Public Cervix Announcement’. With hand-drawn diagrams of anatomical body parts, the show was part awkward burlesque, part parodic sex education demonstration.

Such work riffs on the one-directional nature of porn, and fractures the objectifying, subjugating gaze. It’s hard to conclude that pornography merely restages bad politics in this work, and instead Sprinkle works to deregulate the limitations of the erotic imagination, productively intervening in the interregnum space between representation and reality.

“Is there any room for agency in pornographic production and representation?”

I do get it, though. Most teenagers aren’t watching DIY erotic art practices and it isn’t necessarily radical feminist indie porn that is moulding young minds. However, it does feel like an assumption of false consciousness to suggest younger generations are simply programmed to act out what they see. What about the wavering, provisional zone where we are allowed to process the projection of an image, toss it aside, learn from it, or usher in the power of its erotic charge?

Isn’t that also where we might need to locate our pedagogy of porn? Isn’t porn, within the material production of itself, where alternative ideas about sex can also be negotiated? Where is the agency in porn (in its status of a mode of production and the slipperiness between art, life and sex) to renegotiate scenes of desire?

Srinivasan does reference other, better types of porn, that might have a “salutary” function. Feminist and queer indie porn, for example, offer “an alternative form of sex education, which seeks to revel in, the sexiness of bodies, acts and distributions of power that do not conform to heterosexual, racist and ableist erotic standards.” She cites Swedish erotic film director Erika Lust as an example of this, despite the allegations of performers who have called Erika Lust and Pablo Dobner out for their unethical sets, boundary violations and sexual assault.

This division between work that calls itself feminist and queer, when working conditions belie such a designation, is a crucial delineation: is porn not an issue of labour first and foremost? A crucial dialectic emerges, then, around what is seen on screen and how

it is made. Can feminist and indie porn really offer a radically feminist vision of porn if how the work is made is not itself materially feminist?

“Isn’t porn, within the material production of itself, where alternative ideas about sex can also be negotiated?”

What is missing then is how the question of porn, and its possibilities for agency or emancipation, hinge not solely on what is being represented and taught, but upon labour, and that any possibilities for agency exist along a continuum, one which is embedded within larger relations of subordination and always operates along an axis of power.

While labour conditions don’t really materialise in The Right to Sex, Srinivasan does outline the historicising and racialising gaze of porn. For Black feminists like Patricia Collins and Alice Walker, porn contributed to a history of sexual violence against Black women’s bodies. Srinivasan then carefully draws us to contemporaneous theorists like Jennifer Nash, who writes that for Black women, “there may be salutary possibilities in sexual objectification”, or that for gay men porn can offer them a “sense of their own objectivity”.

But Srinivasan is still sceptical. She writes: “why does the fem gay man or Black woman need to watch someone who looks like them be bent over and fucked to know that they, in their femness or Blackness, are desirable?” This is undoubtedly true. But in watching someone who looks like them getting bent over and fucked, is there not a glimpse of agency in changing the affective script, to return the gaze, to refuse what we have been taught about hierarchised regimes of desire?

For those who are so readily subject to the violent racialising and gendering politics of desire, is there any room for agency in pornographic production and representation? Is there space to refuse the demands of such violent legibility?

In her book A Taste for Brown Sugar: Black Women in Pornography, Mireille Miller-Young explores how Black women producers and consumers of pornography have sought pleasure, subjectivity, and agency in pornographic representations, where they can intervene in the circulation of their representation from within, against ongoing histories of enslavement and colonialism.

Research like this is important in remaining conscious of what Srinivasan herself calls the “necessities of negotiation under oppression”. Miller-Young (associate professor of feminist studies at the University of California) raises a similar question: “I have been asked if Black women pornographers really flip the script on objectification and exploitation, or if they are simply complicit in reproducing bad stereotypes?”

Srinivasan warns against mistaking shifting modes of exploitation for what she terms “signs of emancipation.” However, that we might not be able to delineate such a clear-cut line between the two is perhaps porn’s most productive problem for feminist thought.

Come As Softly is a book column dealing with intimacy, desire and sex

Bryony White is a London-based writer and academic