Imagine a house that you could live forever in. What does it look like? Do its walls slope? Are they made of fish scales? Do they give off an incandescence that seems to change with the time of day, the year, the weather? Is its kitchen shaped like a fried egg? Is the living room a sun-drenched valley, or a stretch of desert dunes to climb over in coffee breaks? Do you sleep upside-down like a cocooned insect, so that every day, upon waking, you could stretch into the limbs of your new body and enter the world afresh?

For the late Madeline Gins and Shusaku Arakawa, two interdisciplinary artists and speculative architects active in the radical postwar art scene of New York, the age-old conundrum of human mortality had one solution: an embodied architecture. Rejecting the modernist idea of architecture as “a machine for living in”, they refuted the Cartesian split between mind and body. Gins and her life-work partner Arakawa sought to develop, in their own words, buildings that would serve as “interactive laboratories of everyday life.”

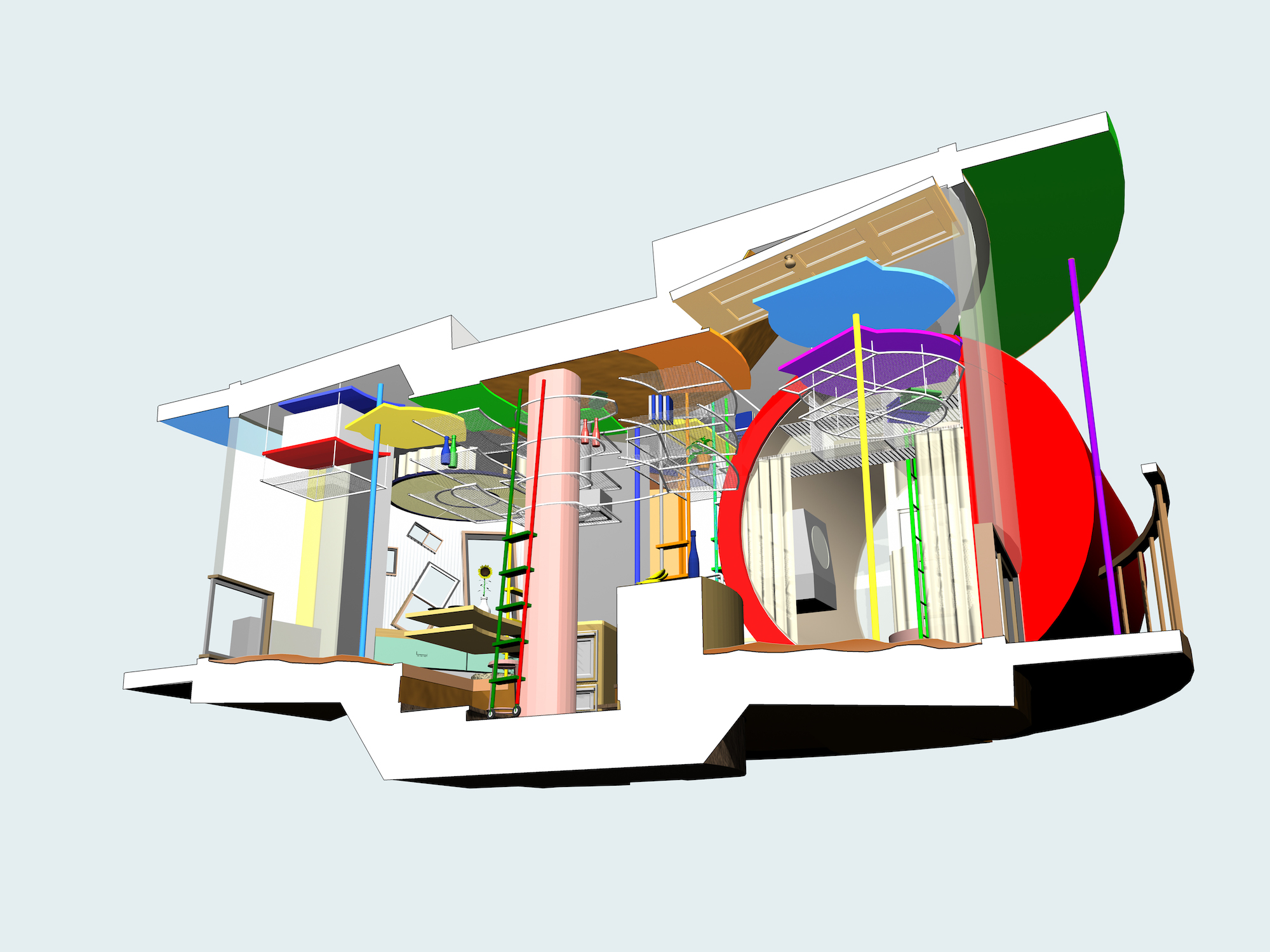

Candy-coloured walls, panoramic floor plans, sunken kitchens, sloping floors and a serious aversion to right angles would keep residents on their toes as they went about their daily business. By challenging and heightening the senses in a perpetual state of tenuousness, the human immune system would strengthen daily; this new kind of architecture, Gins and Arakawa believed, could help residents live forever.

“We have decided not to die,” reads the catalogue of Gins and Arakawa’s 1997 Guggenheim exhibition, Arakawa + Gins: Reversible Destiny. The succinct declaration perfectly encapsulates their lifelong ambition, and is consequently picked up by much of the writing on their work. But long before they established the Reversible Destiny Foundation in 2010, or began to realize their architectural projects in the early aughts, Gins and Arakawa fleshed out these ideas in a body of collaborative works that spanned poetry, painting, film, drawing, and performance.

“Candy-coloured walls, sloping floors and a serious aversion to right angles would keep residents on their toes”

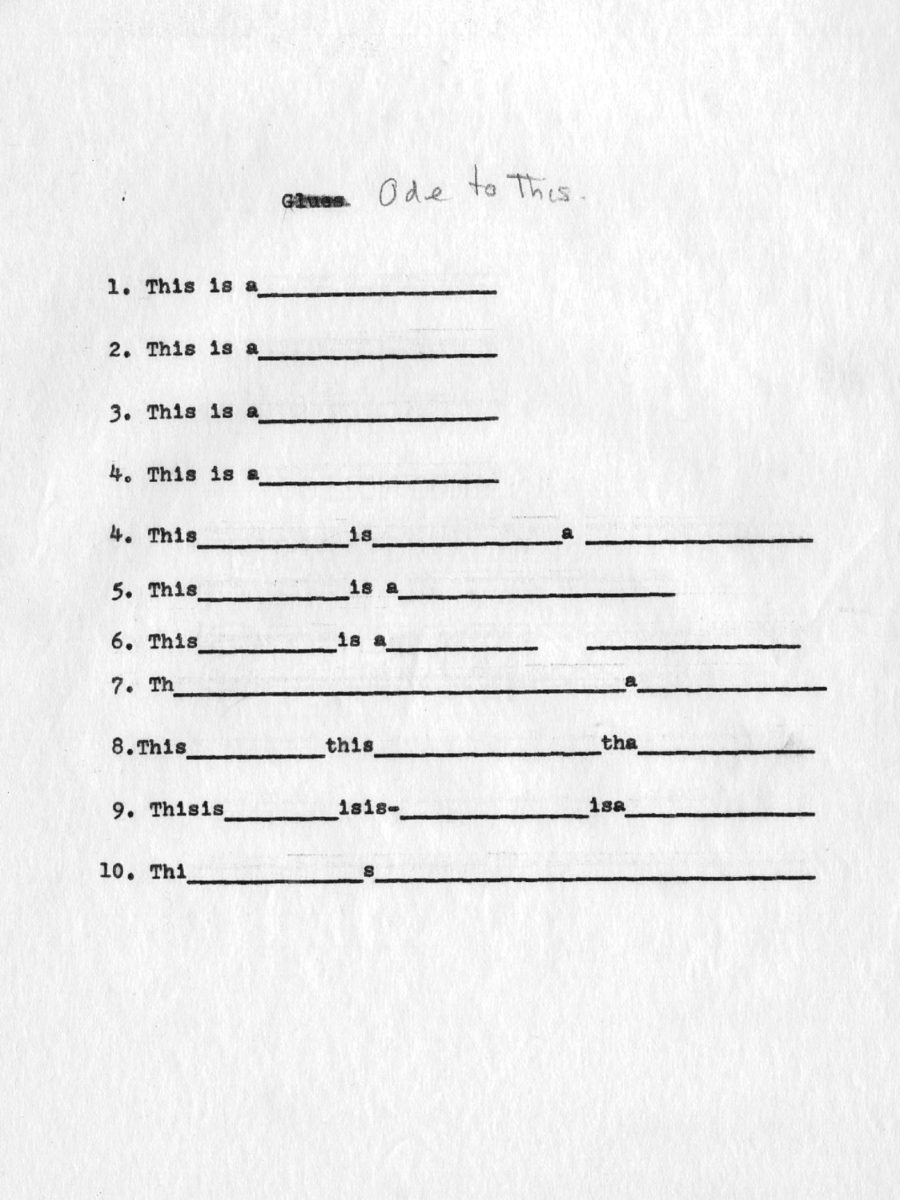

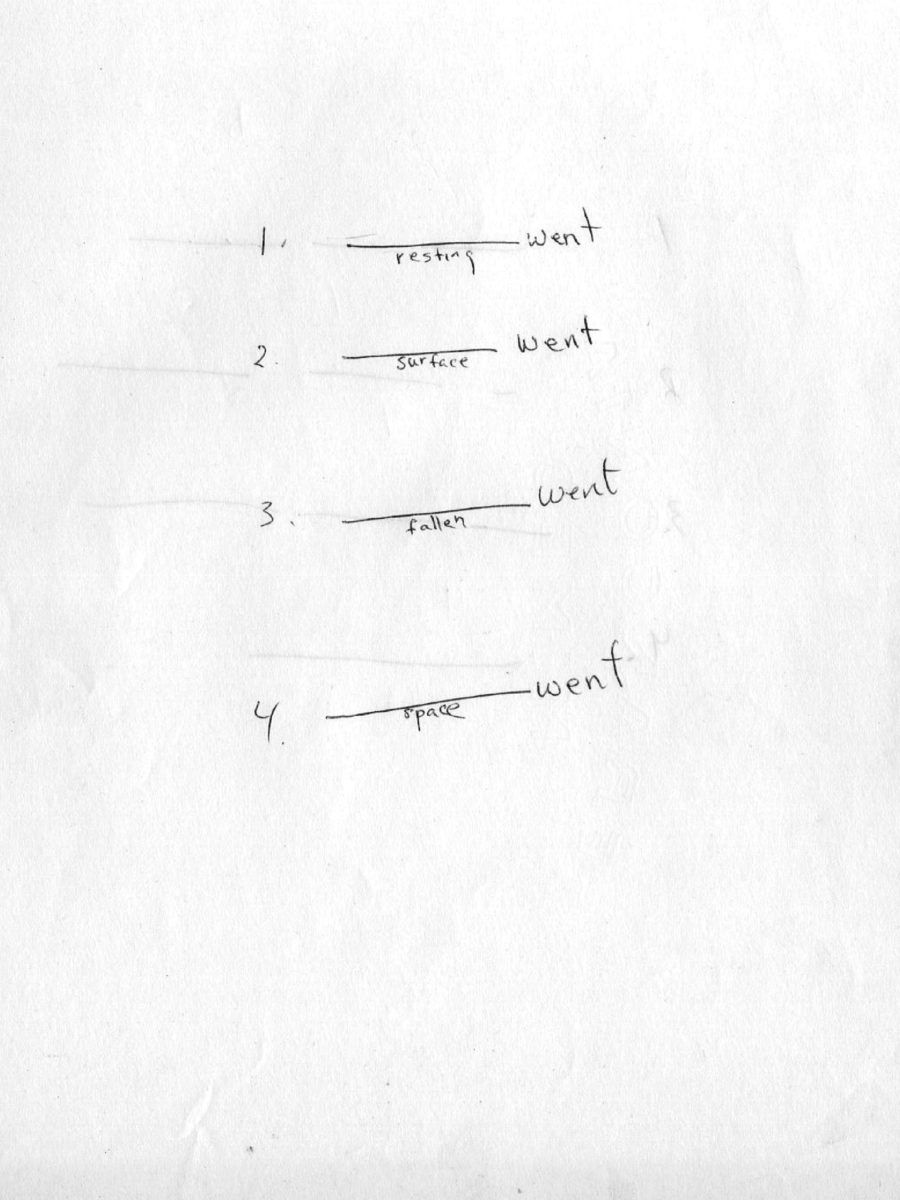

Their first shared project, The Mechanism of Meaning, was initiated in 1963: a year after the two met while studying at the Brooklyn Institute of Painting. An indication of the intensity and duration of the collaboration to follow, the resulting open-ended series of works spans two editions and three decades. It includes over 160 painted panels, charcoal drawings, and later, when the technology became available, computerized renderings. Using text, found objects and images, the works function as a kind of visual puzzle that questions the precise intersection of art, experience and thought, often picking apart meaning language through instruction and play.

In City Without Graveyards, a double panel digital drawing included in the first edition at Guggenheim, Gins and Arakawa propose a sprawling, dense city. Out of this sprout clusters of Rotational Houses, kinetic residences that align their angle to your mood. Death and the spectacular possibilities of its absence was a key theme running throughout their work, in a powerful collaboration that acted more like a singular brain than a shared practice.

As Arakawa continued to explore viewership and the body through painting, Gins used writing to uncover the relationship between reading and the body. For both artists, language was a tool to open up the worlds constructed on canvas and in words. Together they built a lexicon of paradoxes, where ambivalent words like cleave (the act of both cutting and joining) and blank (simultaneously suggesting absence and presence) brought viewers and readers into a state of suspension and unknowing; a state understood by Gins and Arakawa to be the gateway to immortality.

Word Rain, a profoundly atmospheric novel by Gins that plays with the multi-sensory experience of reading, can be found (among her other world-bending writing) in a new Gins reader, published by Siglio Press and edited by Lucy Ives. Reading it, I am reminded of a passage from Olga Tokarzuck’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel, Flights, first published in English in 2017: “…a thing in motion will always be better than a thing at rest… that which is static will degenerate and decay, turn to ash, while that which is in motion is able to last for all eternity.”

- Excerpts from The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had to Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader (Siglio, 2020)

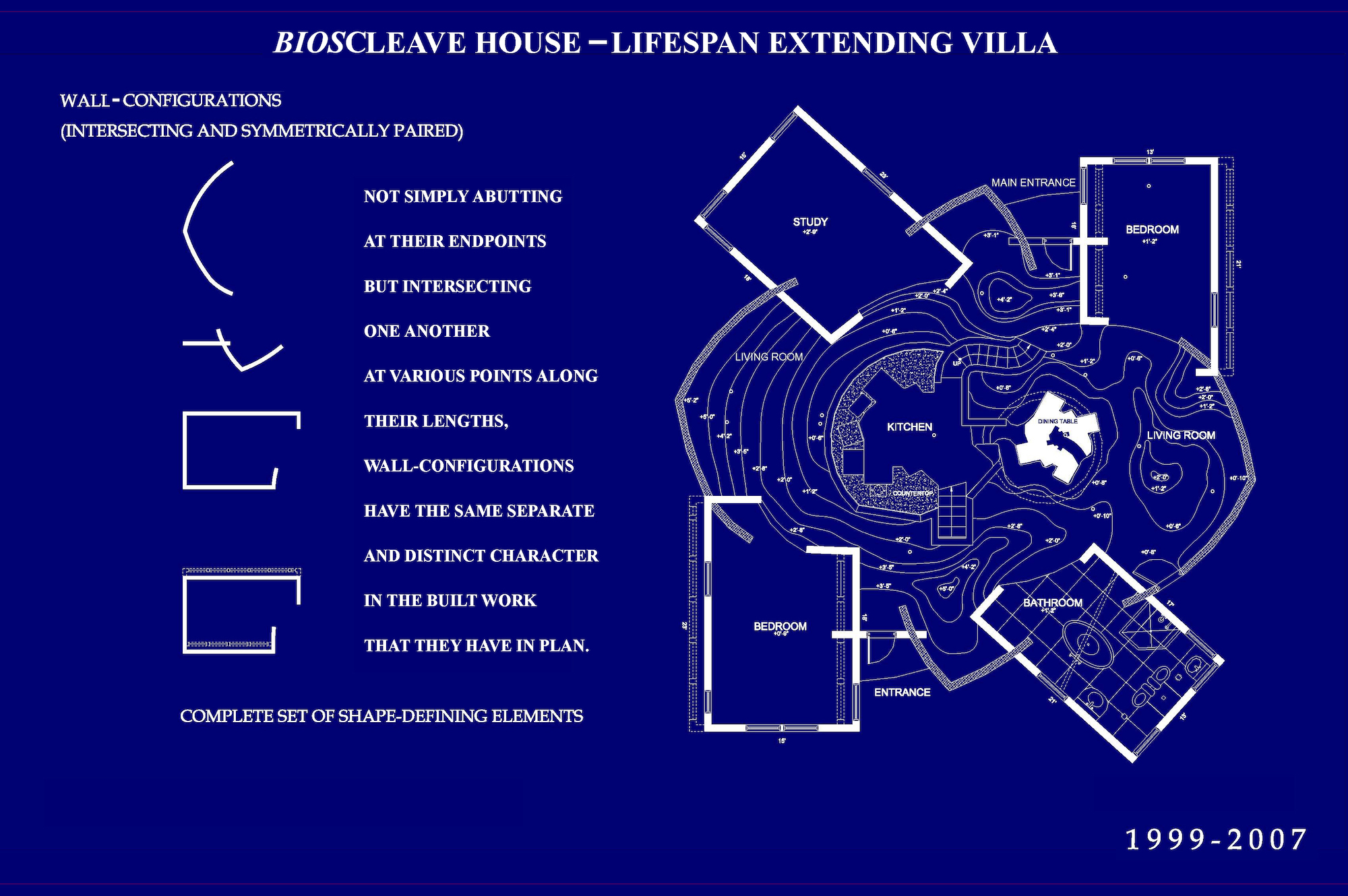

Back in Gins’ and Arakawa’s world, these ideas were eventually sublimated into built projects where ideas of an “architectural body”—their term for the blurring of the boundaries between human and architecture—could take shape. By designing a building whose unconventional shapes, textures, colours, and forms could keep its residents forever in a state of tentativeness (and even a state of flight), Gins and Arakawa believed they could out-design death. In addition to many unrealized large-scale public projects, the Reversible Destiny Lofts in Tokyo and the Bioscleave house in East Hampton, New York are two projects that survive the artists, who ultimately could not defy their own mortality.

“A thing in motion will always be better than a thing at rest… that which is static will degenerate and decay, turn to ash”

I will describe these houses as best as I can in words, although this is an architecture of feeling. In the bioscleave house, a radial floorpan mostly consumed by an undulating, desert-like, bizarrely bumpy landscape sprouts off into four separate rooms. Semi-transparent walls divide space but also merge it. There are no internal doors. Windows appear in unexpected spaces, as do the various vibrant poles ready to support you in your perilous journey to the central sunken kitchen.

Things get even wilder in the lofts. The martian floor is back, this time accompanied by climbable office pods, tubular bathrooms and earthy, pebble-lined bedrooms. With nine flats in total—technicolor cubes and cylinders stacked in rows of three like a psychedelic Jenga tower—it’s easy to picture the daily reality of this dream: groggy city-dwellers stumbling across the landscaped living room before dashing out the door for their morning commute.

Does the residents’ startling out-of-body experience, normalized through daily ritual, change their relationship to architecture? Architecture, after all, has long been considered the discipline of order and control. Does it change who they are? Who would, in Gins and Arakawa’s words, put up with this inconvenience to “counteract the usual human destiny of having to die”? Needless to say, I find it interesting that only one of the nine lofts is occupied by an architect, but perhaps that says more about the conservatism of the field than anything else.

“To out-design death is a position of action, of wanting to dismantle and redefine the logic of architecture, of whom and what it serves”

Reflecting on the Reversible Destiny’s legacy has been an interesting experience in lockdown, with the reality of one’s spatial limits. In an expensive, cramped city like London, the jazzy, roomy villas and lofts become something of a surrealist’s pipe dream, a fantasy game for affluent city dwellers with the time and resources to speculate in such grandiose, if eccentric, settings. After almost three months of my new daily routine, shuffling those few steps from bedroom to bathroom and then down to the “office” (which, for some house-sharers in this city, is back to the bathroom), there are days when I struggle to imagine anything less mind-bending than this not-so-great indoors.

But I also feel something else. It’s the feeling of shelter and safety of having an indoor space to be during in this time, and the intense privilege of that. Reading and feeling Gins’ and Arakawa’s work in this time has shown me that their so-called plan to out-design death is less literal than a state of mind. It’s also a position of action, of wanting to dismantle and redefine the logic of architecture, of whom and what it serves. Their only public project, Yoro Park in Japan, seems to speak more to this than their houses.

As the old world crumbles under the weight of a capitalist society starved of its financial velocity, with a global economy no longer able to keep its subjects in order, there is ecstasy in seeing an alternative future already materializing, as lockdown ends and our worlds expand again into one. “We hope future generations find our humour useful for the models of thought and other escape routes they shall construct,” suggest Gins and Arakawa. In designing these new platforms of resistance, their Reversible Destiny project might be a good place to start over again.

The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had to Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader

Edited by Lucy Ives, out now with Siglio Press

BUY NOW