Sabba Khan, Drawing Power

Sabba Khan and I have been mutuals on Instagram for some time now. We’re nestled within that slightly awkward space—shyly admiring each others’ work and chatting over DMs, but never quite managing to meet in person. So it was fitting that when we finally did get to chat over a glitchy Zoom call, there was an outpouring of emotion on both sides of the screen. Emotion is a tool that is heavily deployed within Khan’s practice—it’s why I relate to her work so much. Having trained as an architect, she recently began to work as a graphic novelist. Khan is a gifted storyteller, and it is this ability to harness the power of both words and images that laces her work with authenticity.

We begin by talking about feelings. “Emotions are a way for me to connect to my gut and my instincts in a way that I’ve not been able to do in other spheres of my life, whether that’s with family, work, university or friends. From what I’ve observed in most people, either emotions are repressed because people don’t have the space to express themselves, or they don’t possess the knowledge to be able to hold those emotions.” Khan explains that this is a historic trend, which is linked to colonialism, rationality and gender politics. “There’s the idea that the male, structured, rational approach to the world is the right one, and the idea that the female, nurturing, empathetic state is volatile and chaotic, and therefore it needs to be oppressed because it will ruin things.”

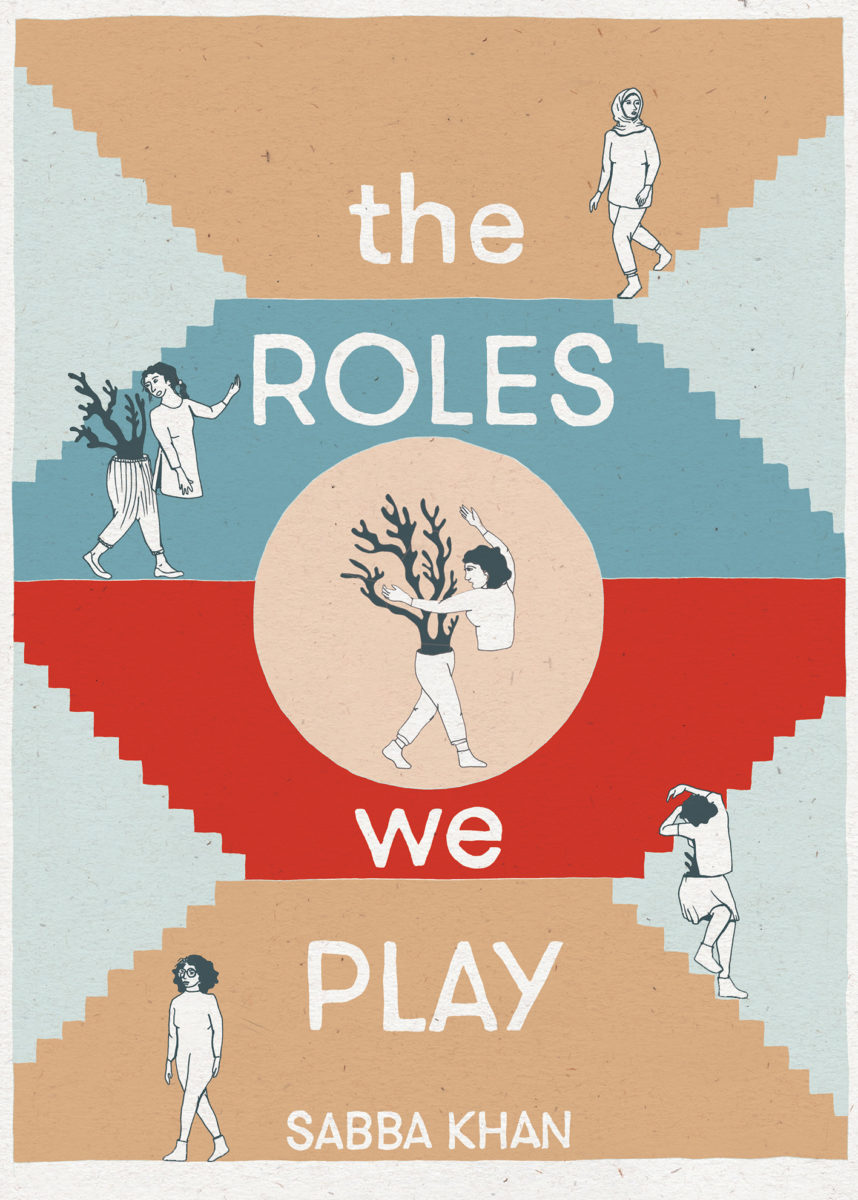

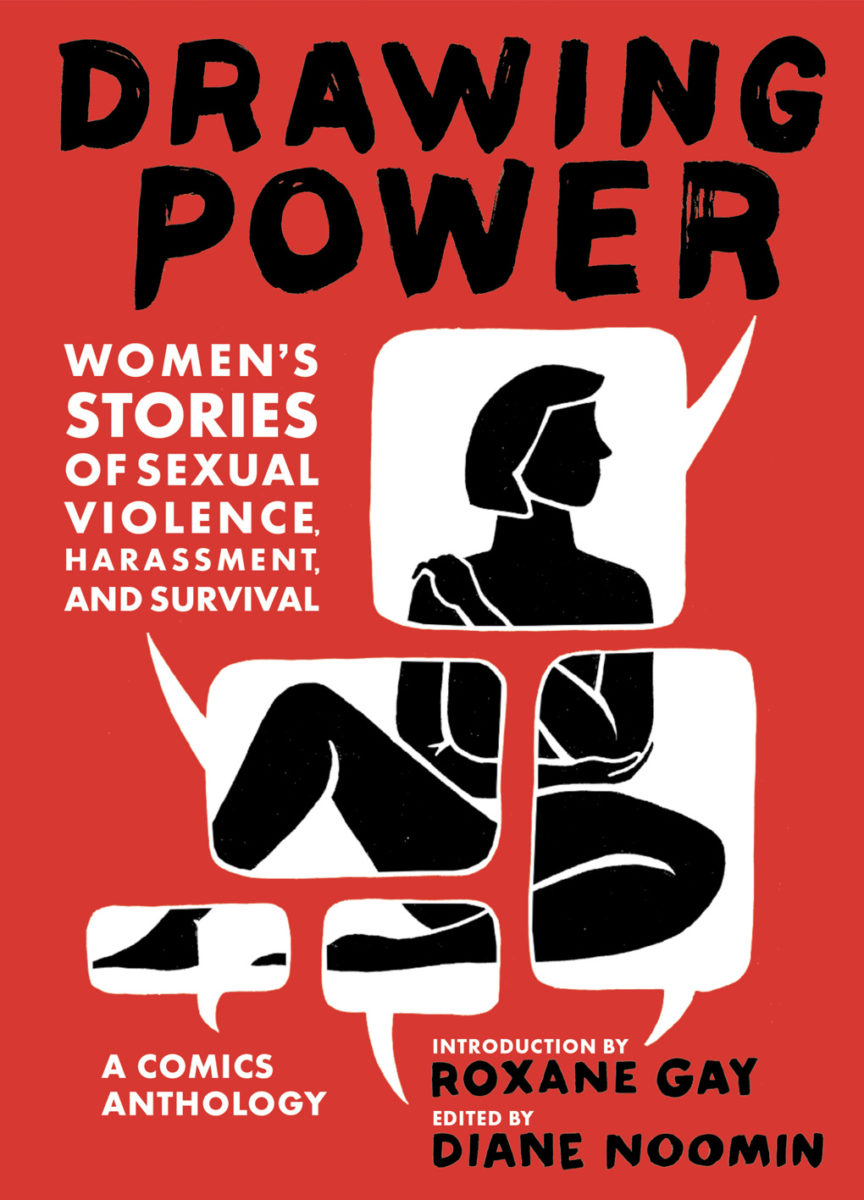

- Left: The Roles We Play, upcoming graphic novel by Sabba Khan. Right: Drawing Power, an award winning comics anthology in which Khan's work is featured.

Khan heard this dichotomy laid out in a podcast episode that identified religious texts, such as the story of Adam and Eve, as the origin story that posited emotion in a negative light. “It’s an ancient concept,” she explains. “Emotions have always been something that I suppressed, so my art practice is about giving them the space to open up; for me to ask myself what things feel like to me. What happened? How do I feel about this event knowing what I know now? What do I want to move forward with, while holding this emotional baggage?”

Does this approach ever overwhelm her? She explains that, in fact, emotions are designed to overwhelm. “We have this idea that you want to be emotional, but not too emotional. But they’re literally designed to take over, shake you up and make you rethink everything. It’s this energy that gives rise to these moments of clarity—epiphanies—which you won’t get unless you’ve gone through the chaos of intense sadness or intense vulnerability or intense anger or even bliss. Some of my best work occurs when I’ve had to go through an emotional upheaval.”

“Both comics and architecture open up questions around people’s lived experiences and the moments that make them unique”

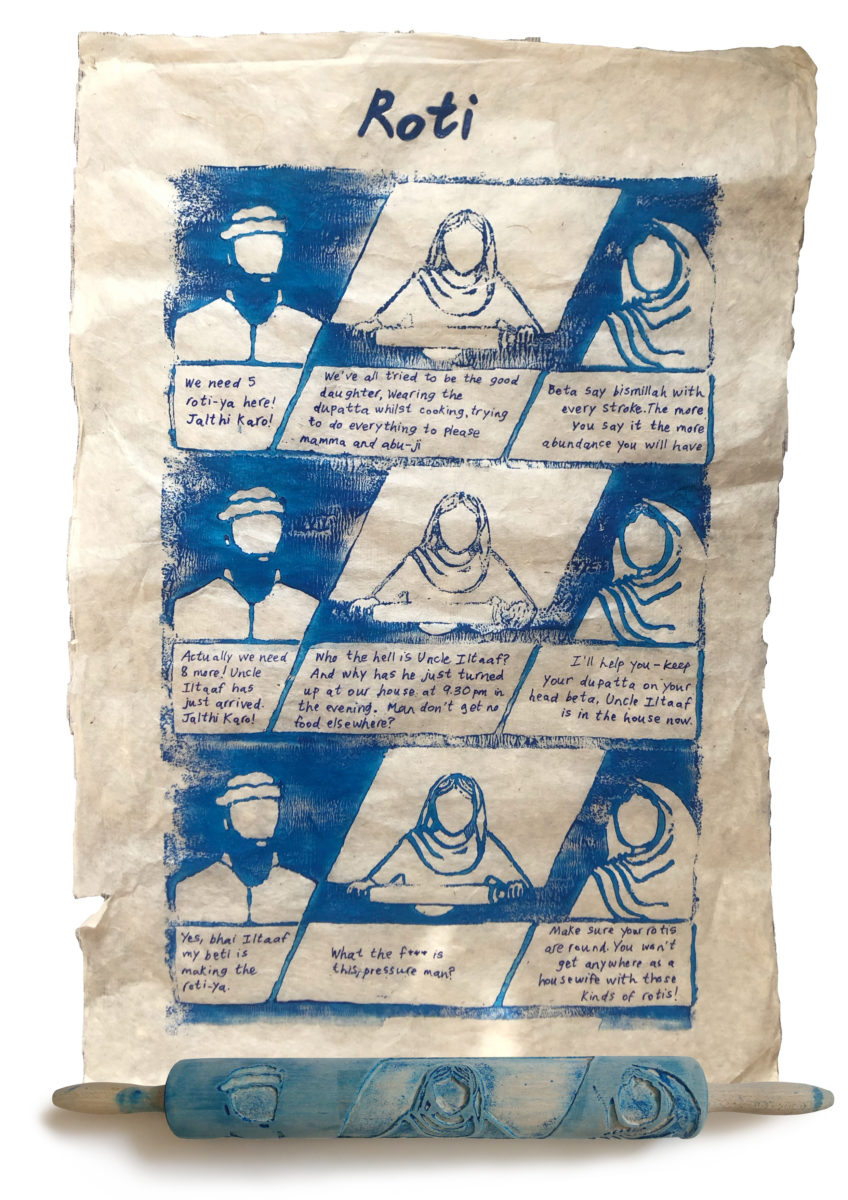

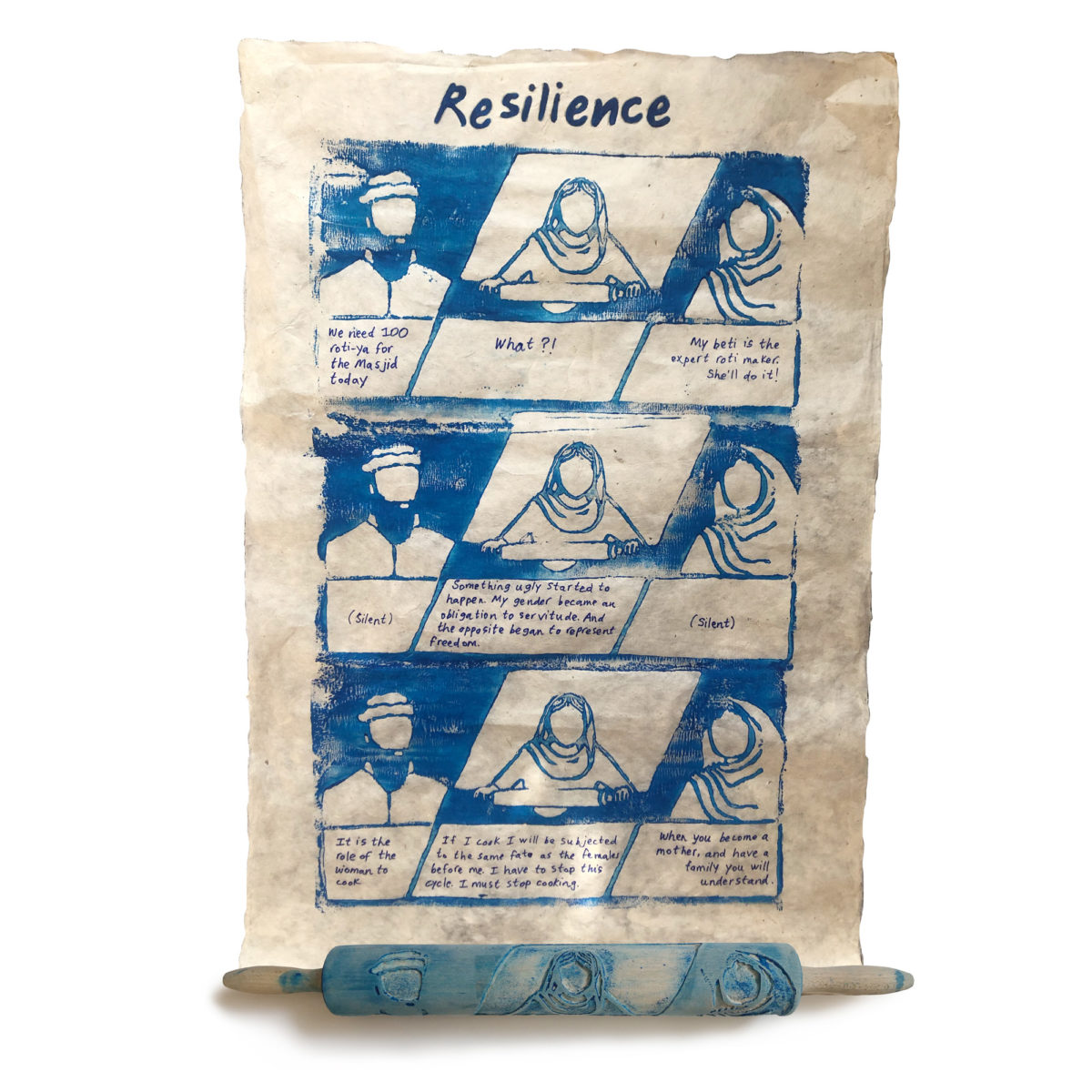

This process, both arduous and cathartic, is evident particularly within projects such as Roti, displayed as part of the exhibition Recipes of Resistance at Ort Gallery, curated by Raju Rage. Khan’s contribution is composed of a wooden rolling pin, into which has been carved a comic strip consisting of three panels. The rolling pin was inked, rolled out onto paper and printed thrice to form nine panels, accompanied by handwritten text that narrates the story underneath each one. The spatial element of the rolling pin brings the experience of roti-making to life—the repetitive motions, the gender-entrenched traditions, the simultaneous anger and satisfaction derived from producing a perfectly round shape.

Khan’s voice guides readers through the comic strip. The first set of panels identify the traditions of roti. “The fact that it’s traditionally a female, domestic, private thing in the kitchen, and it’s done to serve the men and the family.” The second page articulates the anger that manifests as a “reaction to being second generation and living in London”, and thus questioning why Khan, as the central character, is forced to make rotis when her brothers aren’t. “If I’m really bad at cooking, does that mean I get to be a man and get away with it?” Finally, she visualises a utopian ideal, divorced from the negative connotations of roti-making. “How could we reframe domesticity so it’s celebrated as this beautiful, empowering thing for women rather than something submissive and subduing?”

- Sabba Khan, Roti, Exhibited at Recipes for Resistance

Khan’s strength lies in the spaces in-between. Practicing within and between architecture and graphic novels, she wields the principles of both disciplines to question both the migrant culture of her parents and the whiteness of the creative industry. She describes architecture as a physical manifestation of a person’s life: a series of moments which are spread across a series of spaces. “Comics are moments of a person’s life that are recorded on the page—they’re very similar. One is spatial and the other is two dimensional, and more representational. Both open up questions around people’s lived experiences and the moments that make them unique, and which they’d like to amplify and ignore.”

“How could we reframe domesticity so it’s celebrated as this beautiful, empowering thing for women rather than something submissive?”

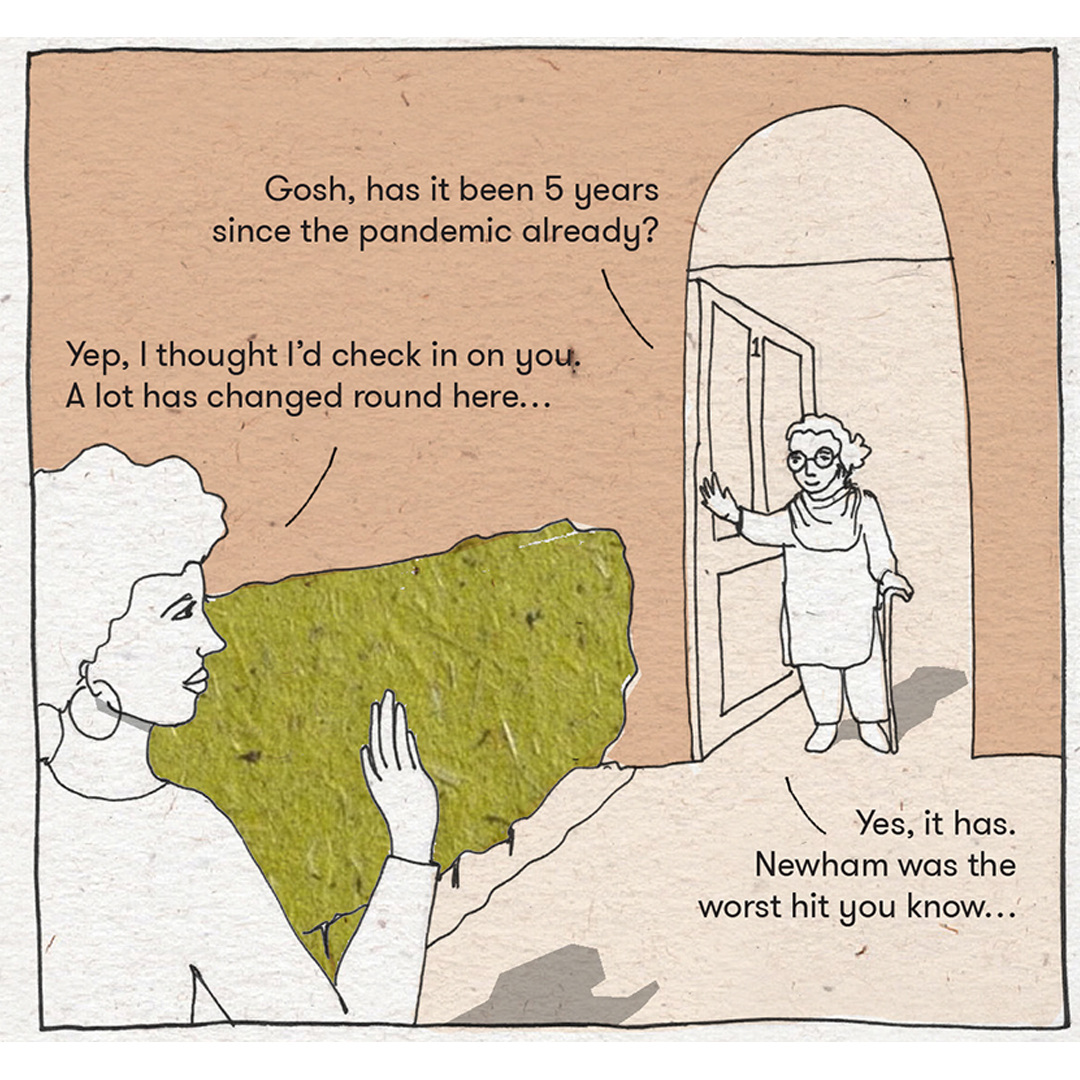

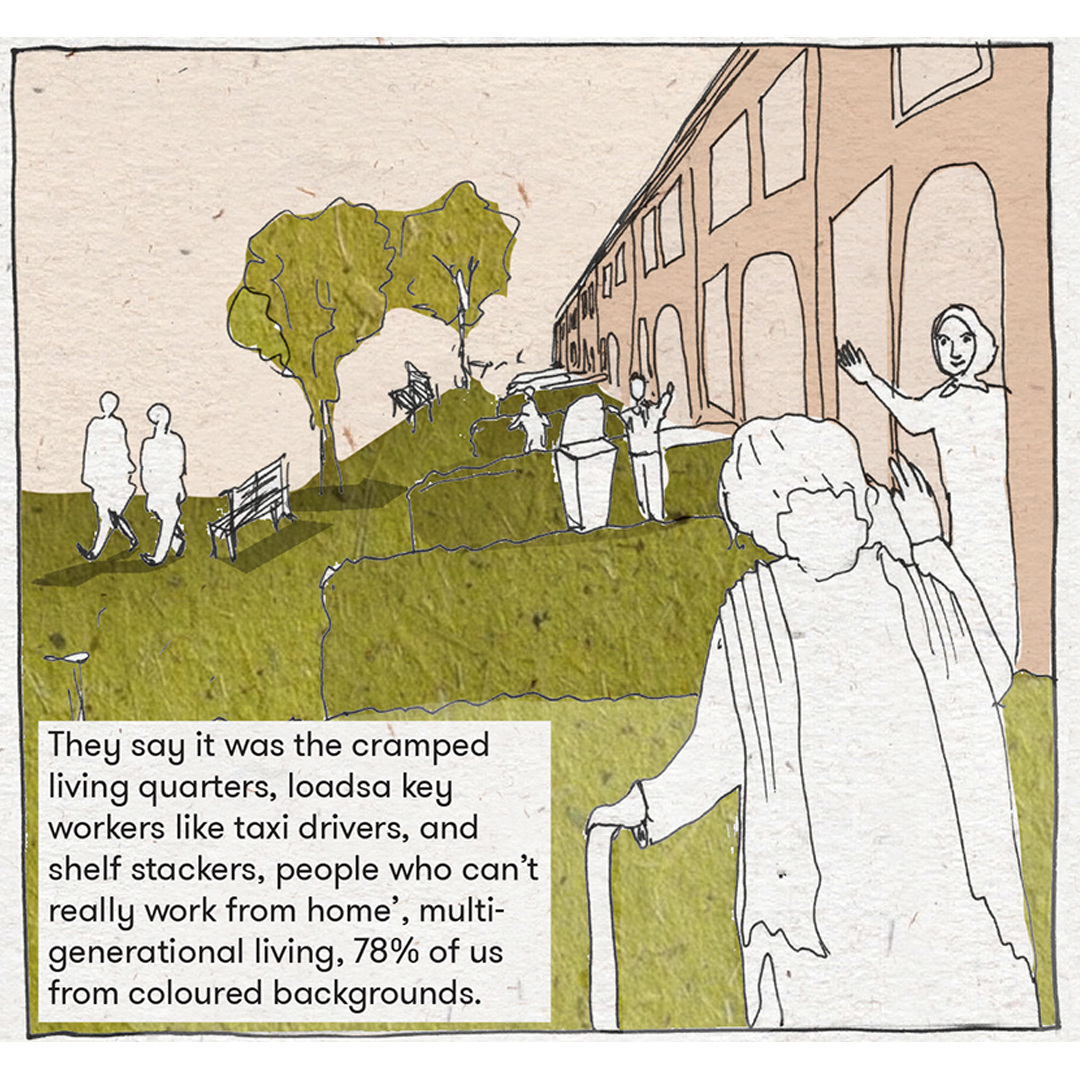

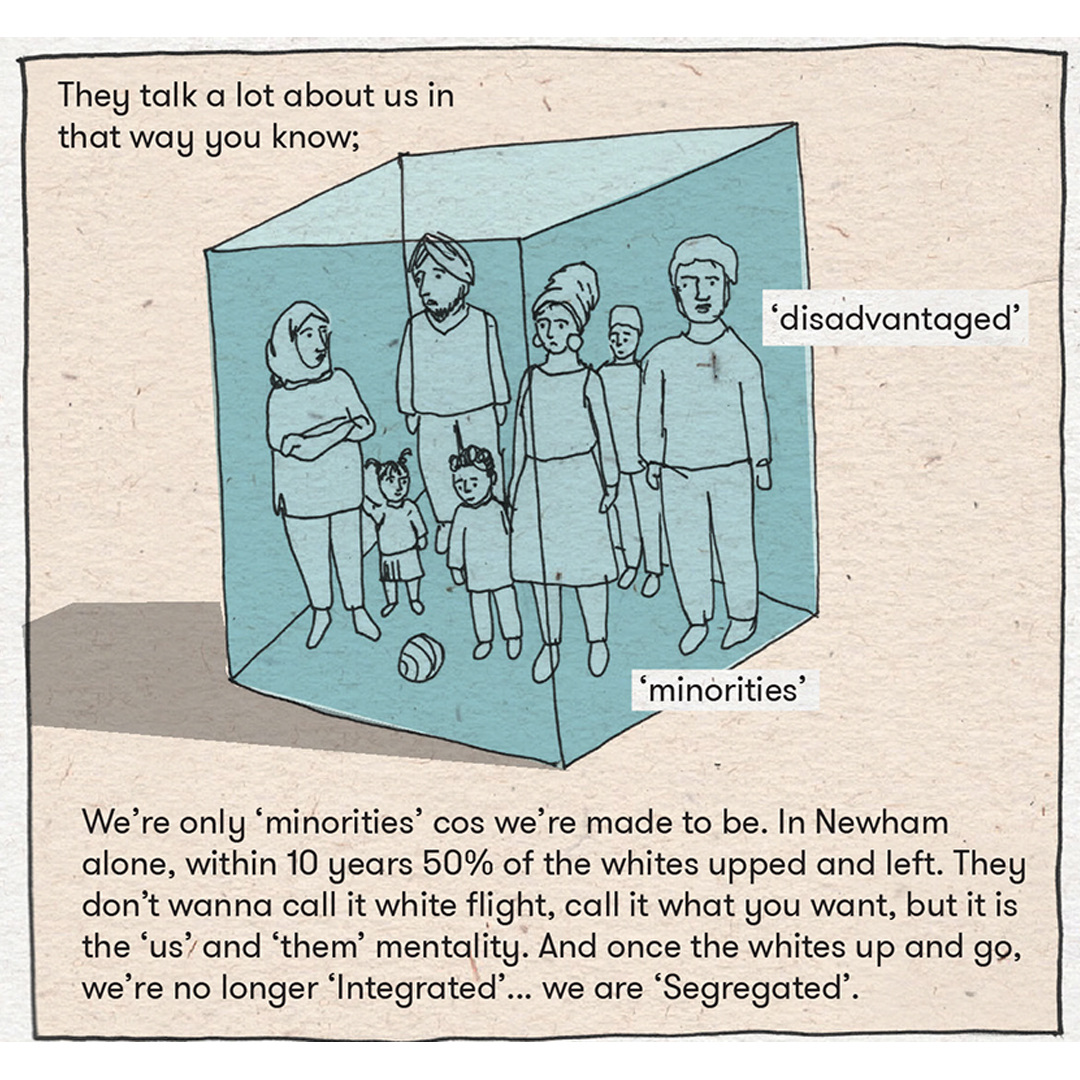

Roti is one project that bridges the gap between these two disciplines, offering the narrative power of a graphic novel. The introduction of the spatial element of the rolling pin, however, is what makes the project sing with originality. Another project that bridges this gap between disciplines is her Eco-Archi Post Covid Comic, submitted in response to RIBA’s Rethink: 2025 – Design for Life After Covid-19 callout, under the moniker Khan Bonshek (Khan’s architectural practice with her partner). The comic takes the borough of Newham as it’s subject, as Khan explains it was one of the worst hit by the virus.

“We looked at some of the more vulnerable communities—the elderly, Black and brown people—those that get sidelined in a lot of urban planning changes. These communities have been there for over 20 or 30 years, and they’ve been expected to move on as migration patterns change and people come and go. We wanted to ask, could our streets be greener?” The duo were creating the proposal during the summer, at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement when the words “I can’t breathe” took on a whole new meaning. They wanted to focus on the importance of breathing, linking this to urban planning and the integral nature of green space, particularly when poorer communities tend to live in more congested, polluted areas.

- Khan Bonshek, Eco Archi Post Covid Comic

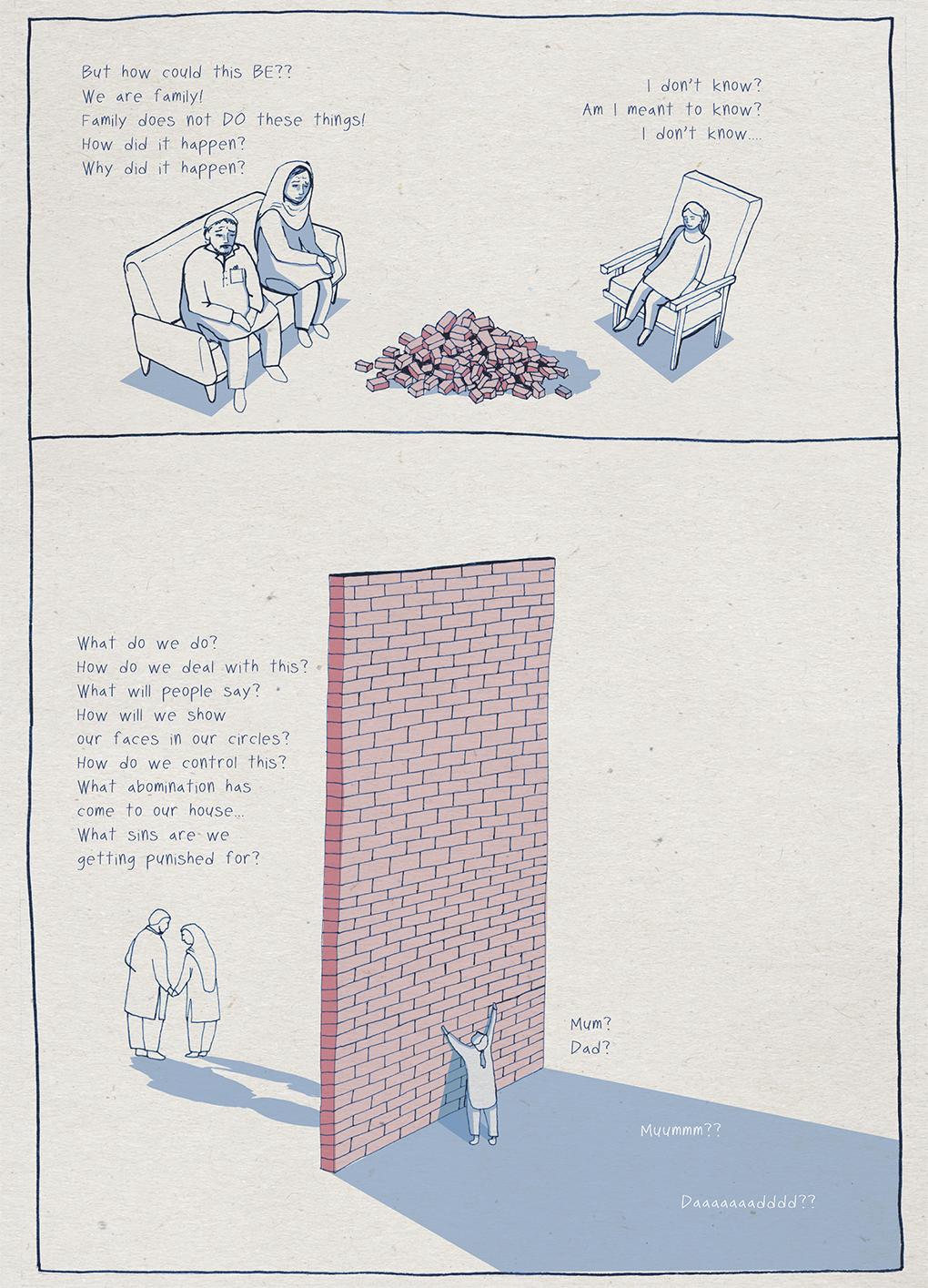

For Khan, community is rooted in the creativity of friends and self-expression. Her close friend, Sofia Niazi, is also a practitioner who bridges the gap between art and design. Niazi co-runs Rabbits Road Press, an independent risograph press in Newham, which is heavily centred around community-building. “Seeing her has given me permission and license to be myself. I come from a traditional family setup, which is multigenerational. So if someone talks to me about community, I think of family and this oppressive structure. As the youngest in my family, and having to hold a lot of emotional space for my parents and siblings, my sense of self was really lost within that structure.”

Khan muses on the relationship between the individual and collective. She agrees that both need to be upheld and respected, but that it’s difficult to engage on a collective level without first identifying your own perspective. “My practice has been a way to galvanise that sense of self, because I don’t think I was able to cultivate it in the architectural industry, which is why I moved away from it. There was no space for personal expression.”

“It’s like a pendulum; I’m trying to find where the authentic self lies between all of these guises that I wear”

We drift off, speaking about the particulars of being South Asian women as part of the diaspora, floating between cultural narcissism, parent-pleasing, and collectivist culture stifling personal autonomy. “The issue with collectivist cultures is that ideally it’s all meant to be for the collective, but very often you have a figure (often the father) who is calling the shots, and everyone within the collective structure is feeding the ego of that main person. Especially with the migration where they may not be getting that sense of power in their work environment, perhaps by being reduced to menial jobs; so they come home and the power dynamic is played out with the mother and the children to feed the ego. That ends up being narcissism.”

The conversation returns to the question of living as diasporic people, existing in between cultures, and gently code-switching between different contexts. Khan recalls having her first (and thus-far only) hallucinogenic, out-of-body experience, last year. “I was looking at myself, floating above my body like a bird, and I could just see her performing. I could see her hesitating and being like ‘what do people think I should say?‘ It was the most sad experience because I was like fuck! This is my life.” She tears up slightly. “Afterward, when I was unpacking what happened, I felt like… I’ve not been allowed to just be.”

The conversation returns to the question of living as diasporic people, existing in between cultures, and gently code-switching between different contexts. Khan recalls having her first (and thus-far only) hallucinogenic, out-of-body experience, last year. “I was looking at myself, floating above my body like a bird, and I could just see her performing. I could see her hesitating and being like ‘what do people think I should say?‘ It was the most sad experience because I was like fuck! This is my life.” She tears up slightly. “Afterward, when I was unpacking what happened, I felt like… I’ve not been allowed to just be.”

Khan’s body of work has a presence as a living, breathing archive. She’s an agent of the personal, documenting experiences for future generations to prise open, in search of a musty memory to identify with. What would she like to be remembered by? “Some of my best work is when I’m closest to this nugget of what I think my art practice is about, which is essentially me searching for my own authenticity. It’s kind of a buzzword, which annoys me, but it sums up what I’m trying to oscillate towards. Especially when the book comes out, it will be the biggest public declaration of my internal happenings. It’s like a pendulum; I’m trying to find where the authentic self lies between all of these guises that I wear.”