It’s the same every year. As we approach Mothering Sunday, Instagram will be flooded with dedications to mummy dearest with old photographs and new sentiments. Honestly, I find the whole thing saccharine and a thinly veiled exercise in narcissism. The pictures are carefully curated to show off your enviable genes—”Look how beautiful mum was and still is”—and an excuse to present the cutest version of yourself, as a child—”Look how goofy I was!” All the while, it’s left unspoken that these are all, obviously, adorable. It’s a kind of emotional clickbait.

Then again, I’m a cynic. Maybe there’s more to this phenomenon of celebrating our mothers on social media. It might reveal a lot about the self-centred tendencies of our millennial generation, but maybe there’s also something deeper going on. The introspective reflex of nostalgia might help us work our way through more troubled aspects of our identity and our relationships with our mothers. By looking back, we also look at ourselves now: what changed, why, and when? Why is it we’ve chosen to share this photograph, for public consumption, to identify privately with our mothers? These images represent, as Anna Furman wrote in The New York Review of Books, “a totem of hope” for our future selves.

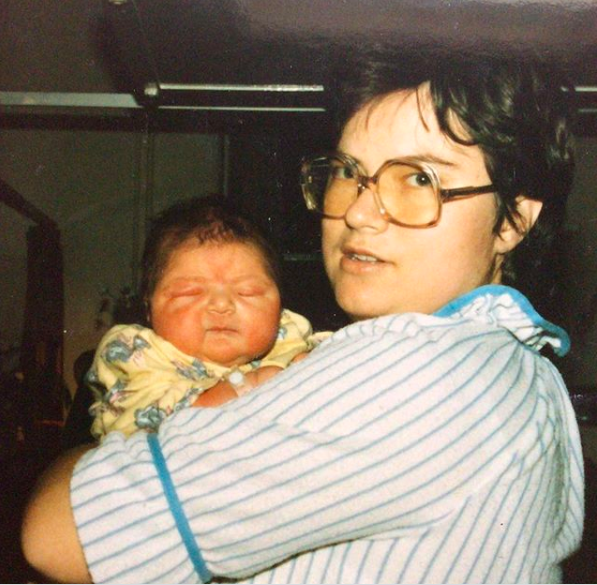

Editor-at-Large Emily Gosling with her mother and brother

I have a complicated relationship with my mother. As the firstborn, the mother-daughter dynamic has always seemed fraught with expectations—and not only in the psychoanalytical sense. Our separation was especially brutal: I was a huge baby and had to be pulled out with forceps after induced labour. My mum then had a postpartum haemorrhage which meant she needed two blood transfusions. It was 1985, when they’d only just started testing donated blood for AIDS six weeks before. Only since giving birth myself can I begin to understand what she went through.

“It’s left unspoken that these are all, obviously, adorable. It’s a kind of emotional clickbait”

As I grew up, we had very different views. When it came to self-image in particular, my mother was strongly against any kind of “vanity”, or what we would now refer to as self-care. You should never spend money or clothes; make-up was banned; haircuts were done in the kitchen by an amateur friend who repeatedly turned me into a mushroom. My sister and I used to pick fruit at the local farm and save the money up for cheap nail varnish, bought in secret then stashed in a drawer out of sight. For years, I was convinced my self-image had been damaged by these experiences—and maybe it was in part. It’s still hard for me to find pleasure in being feminine as I understood it to be something shameful.

No doubt another complexity in our relationship is the fact that she is white and, with my mixed Sri-Lankan heritage, I am not. She grew up in a city with parents who both worked full-time, while she became a “stay-at-home” mum, raising us in a rural area. What photograph could I post that could capture the nuances of our dissonances, the rough edges and the tensions we continue to navigate? Scrolling through the endless odes on Instagram this weekend, the idealized images of mothers who I’ll never meet, I know I’ll feel ill at ease.

The artist Arshile Gorky was preoccupied with a photograph of himself and his mother, taken in 1912 when the artist was eight years old. In the black and white picture, a formal portrait taken in a studio, the young son stands next to his seated mother. Both are unaware that six years later, his mother would starve to death, a victim of the brutality of the Ottoman Turkish Empire against Armenians. The photograph became the reference for his painting, The Artist and His Mother.

“We’re enthralled with photographs of our mothers because we want to understand ourselves better”

Photography, for some, is a way to deal with grief. Photographers like Lebohang Kganye and Avia Wyse have used the medium to navigate their own sense of loss and identity after losing their mothers; for Kganye, that has been direct, superimposing her own image with her mother’s; for Wyse, it has been implicit, an invisible but constant search to locate some kind of protective female figure outside of herself. The artist Camilla Greenwell also used photography to deal with her own pain after losing her mother aged fourteen, creating staged photographs of mother and daughter.

Gillian Wearing inhabited her mother’s image directly in her 2003 Self-Portrait as My Mother Jean Gregory, part of her famous Family Portrait series. Wearing’s self-portrait proves how much we recognise ourselves in our parents, whether they are present in our lives or not. We’re enthralled with photographs of our mothers because we want to understand ourselves better, as if these photographs hold some mysterious key to our character, or have the ability to set us free.

As far as we can go back to the source of our existence, we end up where our life as we know it began: inside our mothers’ bodies. The image of our mother has the power of both life and death within it. Then again, these photographs might, after all, just be an innocent celebration and gesture of gratitude. So: thank you, mum.