Writer Katie Tobin considers the trope of the angel through the history of art, urging readers and artists alike to break free from the traditional feminised and ‘beautiful’ depictions.

Ethereal beings adorned with haloes and flowing robes, their countenance serene, wings unfurling, surrounded by a warm glow. Found in ornate Renaissance frescoes and Gothic stained glass windows, this is the prevailing image of the angel in art. Though there have been some variations throughout history—it was not Christian artists who first painted angels with wings, but rather Byzantine artists who introduced wings in gilded mosaics and intricate panel paintings—one thing remains constant: these depictions tend to emphasise the angels’ grace and delicacy, qualities synonymous with the feminine. This tendency of feminization raises questions considering that angels are, in their very nature, androgynous. What is it about artists painting angels as women?

Although the female angel didn’t formally appear in art until the 19th century, femininity has long been part of the angel’s delineation. During the mediaeval period, artists embraced Byzantine conventions, integrating angels into illuminated manuscripts and paintings. These angelic figures graced scenes of religious importance, often accompanying depictions of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, serving as messengers of divine will. The Italian Renaissance, however, marked a transformation in the portrayal of angels, as artists endeavoured to harmonise classical ideals with Christian theology. Angels took on a more human-like appearance, reflecting a growing fascination with naturalism. Visionaries like Fra Angelico and Sandro Botticelli painted angels with tranquil expressions and delicate movements, frequently depicting them engaging with Biblical figures in intimate settings

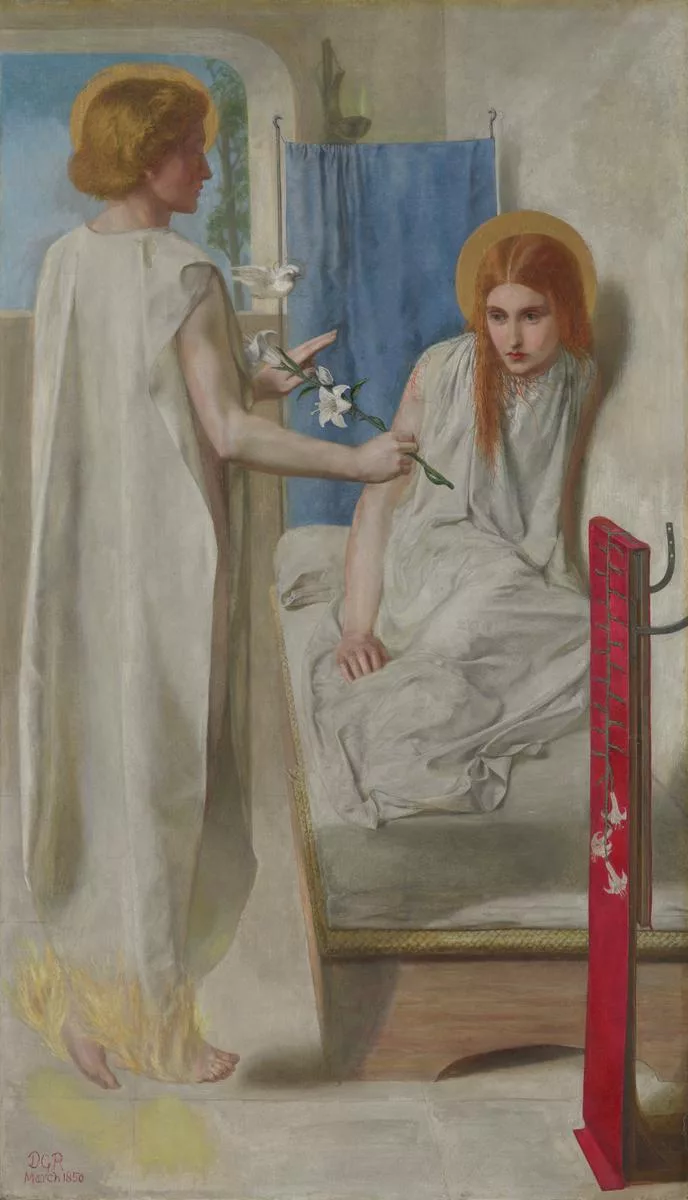

In the Neoclassical era, artists persisted in drawing inspiration from classical antiquity, presenting angels as idealised embodiments of beauty. Works by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, such as La Naissance de Vénus (1879) and La Vierge aux anges (1881). In Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc (1879), Archangel Michael appears to Joan in her parents’ garden in Domrémy—not all too dissimilar to the Biblical Annunciation scene where Archangel Gabriel appears to Virgin Mary in Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation) (1849–50).

And the fascination with this religious iconography didn’t fade. Later on, modernists Paul Klee and Marc Chagall continued the tradition of turning to the Bible for inspiration in the 20th century. Chagall often painted angels because, as he put it, “it always seemed to me, and it still does, that the Bible is the greatest source of poetry that has ever existed. Since that time, I have been seeking to express this philosophy in life and art.” In most of his works, angels are depicted as feminine, with long hair and dresses, traits which can particularly be seen in his aptly named 1969 painting, The Female Angel.

This is all to say, that angels have long been codified with feminine traits, even if they’re not explicitly painted as women. Although there is no singular explanation as to why this is the case, one speculation includes the historical and cultural associations between femininity and servitude (they are, after all, literal servants of God). But where does this leave the art angel today?

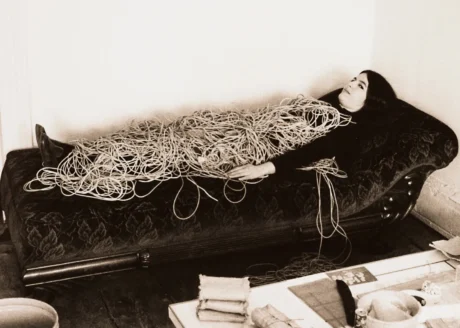

I recently found myself asking this very question at the National Portrait Gallery’s Portraits to Dream In, where a whole section is devoted to “Angels and Otherworldly Beings.” Although the show centres on the idea of a shared visual language between Julia Margaret Cameron and Francesca Woodman, a photographer working a hundred years after the former, it’s the differences in their work that I was most drawn to. The images taken by Cameron—a British artist from a family who was deeply involved in British colonial India’s economy and bureaucracy —are distinctly Victorian. Heralding the dreamy quality of Bouguereau’s paintings, Cameron’s sepia portraits are rich with Biblical imagery: cherubs, saints in prayer, and prophetesses. Beautiful, but nothing we’ve not already seen.

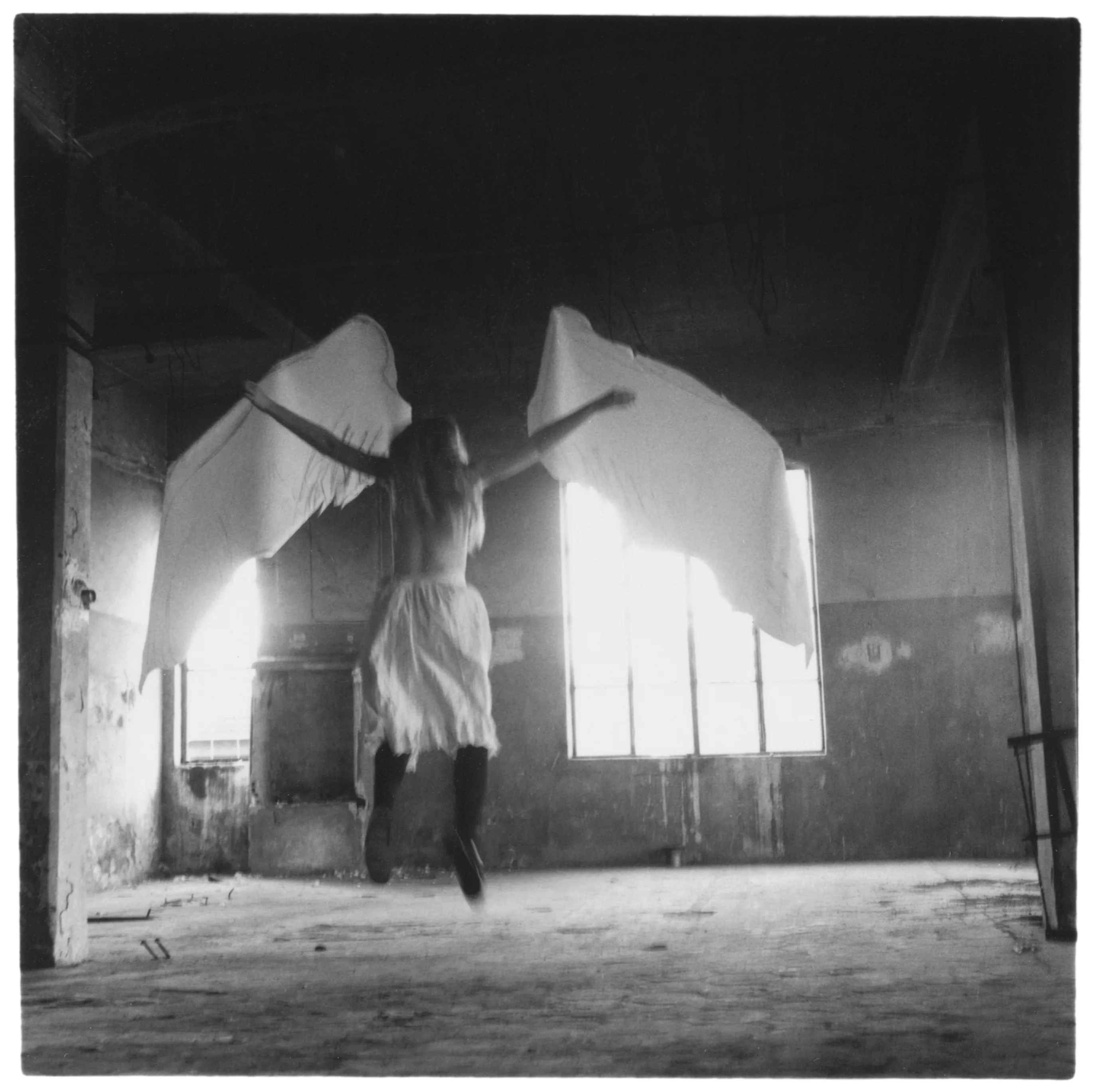

It’s here where Woodman’s photos might serve as an interesting juncture to traditional and more modern representations of angels in art. Unlike earlier depictions of angels, hers become a conduit for probing deeper questions about identity, gender, and self-reflection. Woodman continually revisited the modified throughout the 10,000 some images she produced over her short career, working against the archetype of the serene and divine beings of classical art and instead offering something far more wild and earthly.

In On Being an Angel (1977) —amongst the most striking of her works—Woodman captures herself in a state of transcendence. Intentionally overexposed, her contorted body is bathed in soft light. It is an image that is both otherworldly and incredibly intimate. But despite the celestial aura, the scene is grounded by quotidian elements: camera equipment strewn on bare floorboards and the silhouette of an umbrella against a plain wall. In doing so, Woodman paints herself as an enigmatic figure through the lens, blurring the line between the physical and the metaphysical. As her exploration of angelic themes developed, her later works delve into darker and more vulnerable territory. Questioning the objectivity of photographic mediums, Woodman’s Angels series shows the artist in constant motion: her body is suspended, her face blurred. What is real versus what may be superimposed, is ultimately unclear. It is liminality—spaces between reality and illusion, presence and absence—that compels her most.

At first glance, Woodman’s treatment of the female nude feels not all too dissimilar to the work of her artistic contemporaries. But unlike her contemporaries, she infuses her images with a raw sensitivity that distils inherent sexual components. While she occasionally embraces explicitness, as seen in Untitled (1980), where suggestive framing and facial expressions hint at sexual occurrences, her oeuvre favours an ambiguity that invites contemplation rather than easy interpretation. Rather than presenting idealised or ethereal figures, Woodman explores the nuances of the female form, infusing her subjects with a sense of humanity and psychological depth.

Meanwhile, in Florence, Anselm Kiefer takes a radically different approach with his angels. Beyond merely the customary themes of mythology, religion, and literature, Fallen Angels engages deeply with the materiality of the Palazzo Strozzi itself. Gold leaf, a hallmark of the Florentine Renaissance, features prominently—mostly notably in a room dedicated to the Roman Emperor Heliogabalus, adorned with Kiefer’s iconic sunflowers. Through his vitrine works, which combine lead and gold, the artist explores alchemical transformation, a practice synonymous with Florence during the Renaissance.

Kiefer’s angels, however, challenge canonical depictions, embodying the struggle between the divine and the profane. In the Palazzo Strozzi’s central courtyard, Engelssturz (Fall of the Angel) (2022-23) spans an impressive seven metres, portraying Archangel Michael against a backdrop of gold. Here, rebel angels, shown dimensionally with discarded clothing attached to the canvas, lie defeated at his feet. This scene, reminiscent of depictions by Renaissance masters like Raphael, serves as the exhibition’s focal point, contrasting monstrosity with opulence. Works such as Luzifer (2012-2023), featuring an aeroplane wing protruding from the canvas, are at once suggestive of both ruination and heavenly ascension. But of the most astonishing of his installations, is Verstrahlte Bilder (Irradiated Paintings) (1983–2023), which covers the walls and ceiling of the palazzo’s largest room. Mirrored surfaces create an illusion of paintings extending onto the floor, resulting in an exposure of overwhelming detail. These weathered canvases, exposed to nuclear radiation, symbolise the intricate relationship between destruction and creation.

Though the aforementioned themes may seem inherently contradictory to one another, these contradictions aren’t new for anyone intimately familiar with Christian theology. Some readings of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) view Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden as a felix culpa or a ‘happy fault/fall,’ ultimately suggesting that the Fall of humankind was necessary to allow for a greater good to occur. Similarly, for mystic and philosopher Simone Weil, the idea of ‘decreation’ is the process of self-emptying or self-annihilation, where the individual seeks to strip away their own ego and desires in order to become receptive to the divine or absolute reality. Indeed, Kiefer’s interplay between transience and transmutation is palpable in every painting—a sentiment made clear by the words of Italian poet Salvatore Quasimodo, inscribed on the walls of the final room: “Everyone stands alone at the heart of the world / pierced by a ray of sunlight / and suddenly it’s evening.”

While Woodman and Kiefer explore the angel through radically different mediums—one through her camera and film, the other through paint and sculptural installation—there’s a surprising convergence in their exploration of identity, spirituality, and the human condition. And more than that, they both seem to frame angels as peripheral bodies, where heaven meets the earth, ultimately defying inherently feminine and subservient portrayals. Art thrives on breaking rules. As Milton and Weil might suggest, destruction need not signify an end; rather, it could mark the genesis of something profoundly beautiful.

Words by Katie Tobin