This Artwork Changed My Life is a new series that explores the personal, often surprising, emotional influence that works of art can have on us, even when we least expect it.

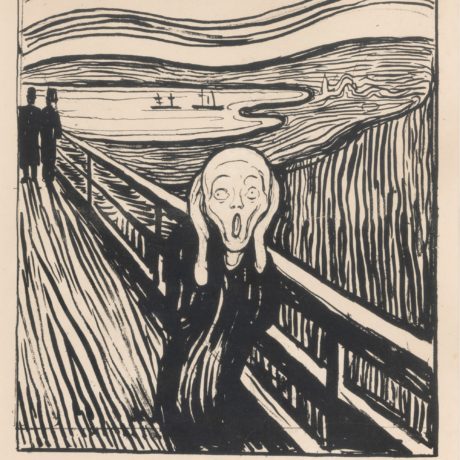

During my final exams for university, at the tail end of my first adult relationship that had ended in a suicide attempt, I changed my Facebook profile picture to The Scream, a painting by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch. Originally titled Der Schrei der Natur (The Scream of Nature) in German or Skrik (Shriek) in Norwegian, it is one of the most recognisable artworks in the world. It’s unclear whether that is the cause or symptom of how it has featured in popular culture.

When I chose it for my avatar in 2012, 119 years after the first version was painted in 1893, it was instantly recognizable to my friends (all in their early twenties). The image conveyed plenty more than any words could at that point in my life. “I’m about to face what feels like the most important challenge of my life at a time when I don’t feel well placed to do anything”, it said, in a light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek manner—in opposition to the internal screaming panic that I was feeling. It was a convenient, somewhat euphemistic, pictorial lexicon for articulating painful and overwhelming feelings to my peers.

The Scream remains iconic, partly because there is something deeply relatable in Munch’s depiction of the experience of mental illness. It seems as though it’s more than just me who thinks this—do any other artworks have an emoji fashioned after them? It appears not just in contemporary culture, but in the popular mainstream. Without having seen the horror film series, I instantly understand what a Scream mask

looks like. It has been replicated and reproduced in so many places as to have become detached from the original image and artist.

“The Scream remains iconic, partly because there is something deeply relatable in Munch’s depiction of the experience of mental illness”

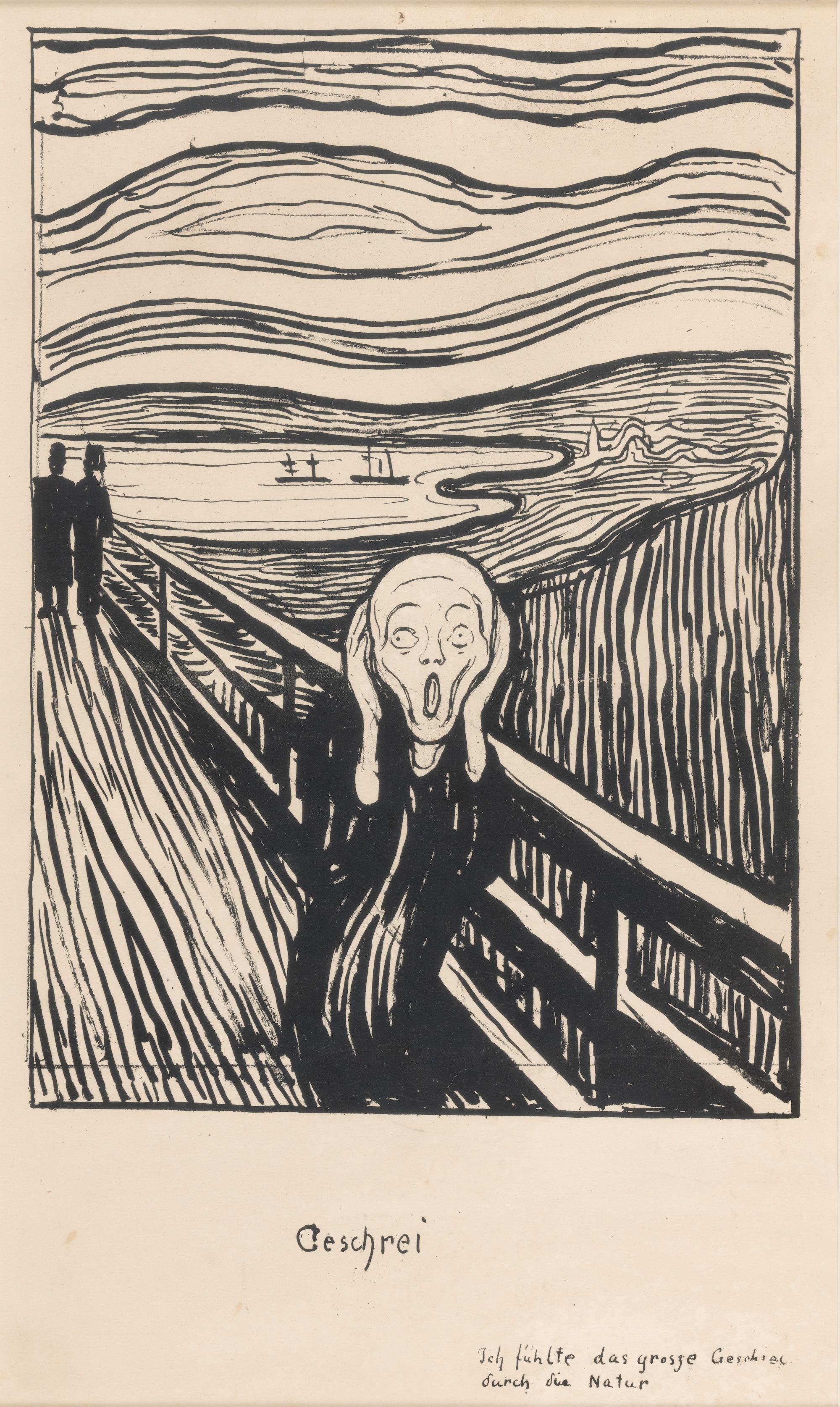

That isn’t meant as a negative value judgement. The artwork was first replicated by Munch himself, who created several versions across different media between 1893 and 1910. My preferred icon for social media is the oil painting on display in the National Gallery in Oslo, all unrestrained reds and gloomy blues. Like the rest of Munch’s Frieze of Life series, the work is an explicit visual representation of the themes explored in the series. Munch himself described the Frieze as “a poem about life, about love and about death”. The distorted primary colour palettes and hollowed faces of The Scream recur in other cheerily titled paintings: Anxiety, Love and Pain which was later renamed to Vampire II.

If I look at my own forms of creative expression, the same imagery and metaphors recur because they clearly resonate with me, and with those who consume it too. Munch, in creating this iconic image which continues to enjoy zeitgeist status, successfully captured a feeling which has only come to feel more and more significant, even to the point of cliché. I remember, when I was feeling slightly less Scream-y in the summer of 2012, reflecting that Munch’s photographic self portraits resembled proto-selfies. He had a knack for capturing the contemporary ahead of his time. Perhaps he was the first millennial, attitudinally, making work a century before the rest of us were born, wearing his anxiety on his sleeve and doing what he could to “make something” of it.

A pet peeve of mine is when the interpretation of artworks in galleries romanticize mental illness and link it to talent—Van Gogh being an obvious example—and this erases the equally valid experience of the many more people who face challenges without any creative outlets. It also ignores the privilege inherent in having that access; Van Gogh himself was able to support his lifestyle because of his very wealthy brother. What irritates me most about this narrative is the suggestion that personal distress is justified in the creation of something beautiful. I don’t believe that people create art just to make something of their pain, and the results (however impressive they might be) are not some sort of consolation prize. Sometimes, people just express themselves.

“Munch successfully captured a feeling which has only come to feel more and more significant, even to the point of cliché”

Indeed, to read some of Munch’s quotations about The Scream, I am taken back to my teenage years: of Myspace, LiveJournal

and MSN messenger screen names belying an inner despair befitting my emo-goth aesthetic. He writes: “Suddenly, the sky turned blood red…there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city…I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature”. A cynical interpretation, that I find myself self-reflexively applying, is that he was aestheticising his depression. When I think of him writing, “All art must be created with one’s lifeblood,” I cringe at the fact that my own source material is me – how predictable, how self-obsessed.

A preferable and more palatable way of considering it is to think of it as a performance that provides distance from one’s own experience: art as a drug-free dissociative. I prefer to think of it this way, and to imagine that Munch felt the same. He felt a feeling, he put it out there and for a moment, the acutely negative feelings were released onto a canvas. It might have been comforting, so he did it again, and again, in other paintings and in prints. It feels simple—and human.

The Scream, for me, serves as a reminder that everyone feels scared or panicked or depressed sometimes. The fame of the artwork is testament to that. It is something to hold onto at times of personal pain. When in February, another romantic affair of mine was going to hell, I was genuinely soothed to hear that The Scream would be on display at the British Museum

, part of an exhibition called Love and Angst. My reaction on hearing the news was to laugh at the serendipity of the title and timing: I would be able to resist calling my ex by instead writing about what it feels like to see The Scream when going through a break-up. I would pitch it to editors to get the same thrill of rejection.

“To read some of Munch’s quotations about The Scream, I am taken back to my teenage years: of Myspace, LiveJournal and MSN messenger”

I was thinking about suicide a lot when I went to see the monochrome print on display at the moment. Not my own, this time, but in the abstract, although it was triggered by concern for a close friend. I didn’t feel particularly moved to see it in the flesh. I felt neutral. I thought about all the people who would pass through the very popular gallery today, and every day, and how they too would register it as an artwork they recognised. It is likely that they too have at some point in their life experienced angst, loss or grief. It struck me how mundane it all is. How very unspecial, to be sad, and yet in the moment it feels overwhelming and unique; it feels as though there must be an extreme resolution.

The fantasy, the romantic notions, that we have been indoctrinated into through popular culture never quite lives up to the reality, which is, more often than not, rather cliché. That is no bad thing. In popularizing pain, Munch made it unremarkable and quotidian and human—which it is. That your situation and your mistakes have been made and felt repeatedly before, like a print from a stone lithograph, is a humbling perspective, and ultimately, funny.

Ari Haque is a Bengali-British writer, focusing on gender, art and cultural identity.