One morning earlier this winter, the sun rose over London’s Shoreditch neighbourhood as I cranked open the gates to my office building. I stacked photographic prints on their way to wealthy collectors. I waited for the computers to boot up. It was 8.30 A.M., and an email from the night before rolled in: Art Dubai announces it is postponing its 14th edition due to the spread of COVID-19. Three minutes later, Frieze New York notifies of its cancellation, then Art Basel Hong Kong.

The earth was changing imperceptibly. Rumours of a city-wide lockdown emerged, for which the globetrotting art world was entirely unprepared. As I spoke with a fine art courier, whose main role it was to careen artworks to and from these shuttering art fairs, he told me he’s used to hopping around work in this business. Yet I worried about his job safety, as I did mine. Like the art market itself, both volatile and intangible, the workers within it are in constant flux.

“The art world is known to be imprecise and impertinent to equity, where only a small percentage at the top can live securely”

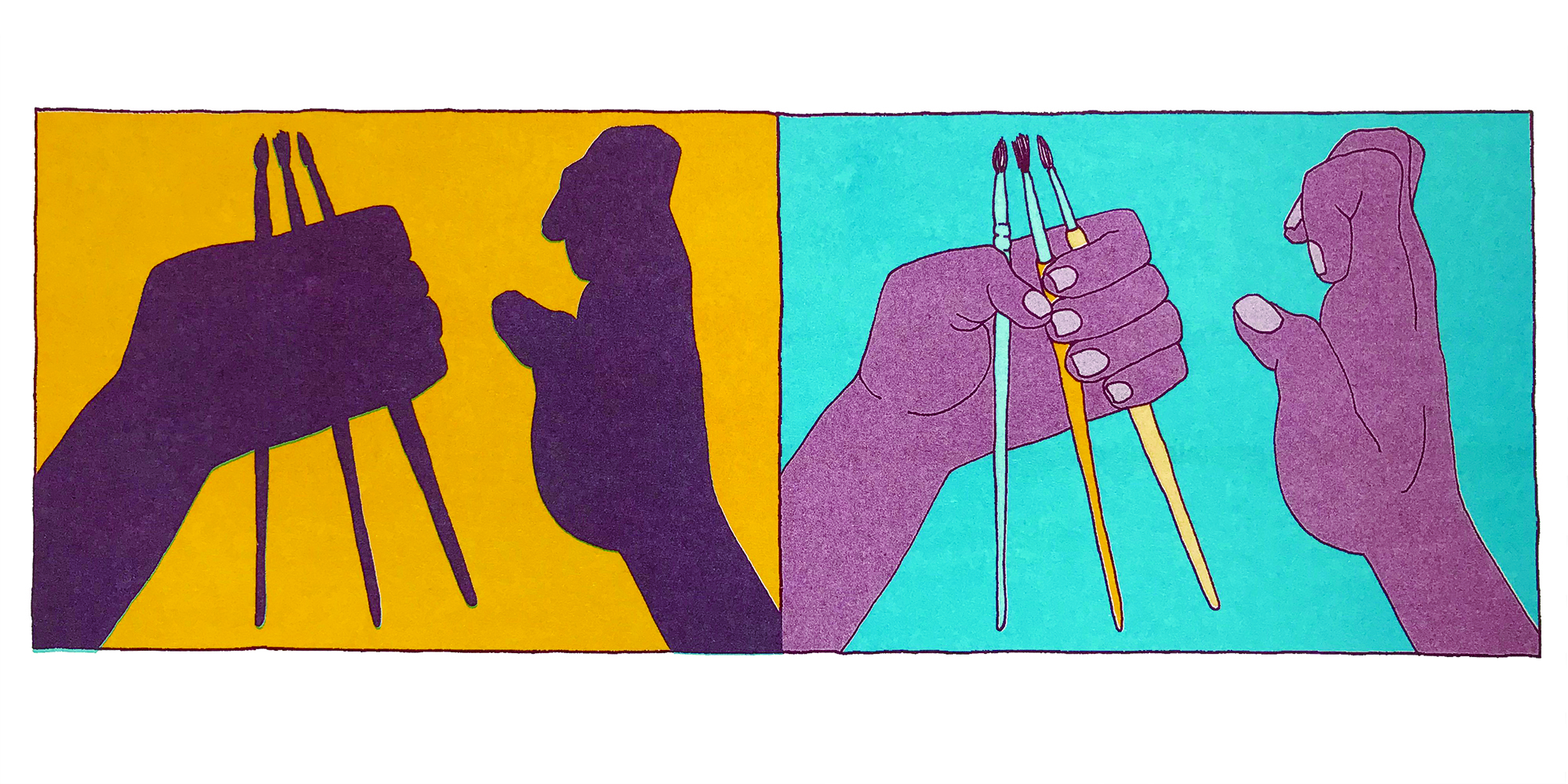

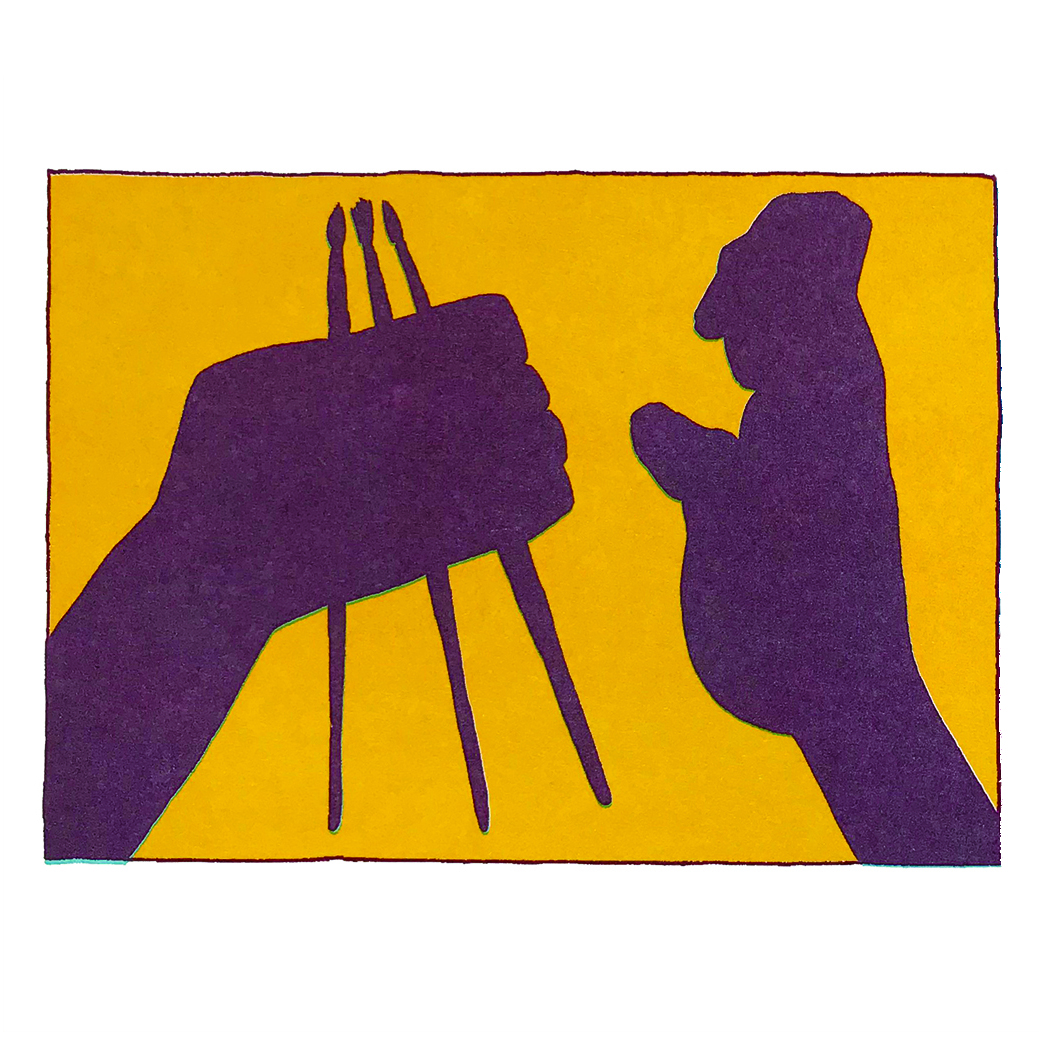

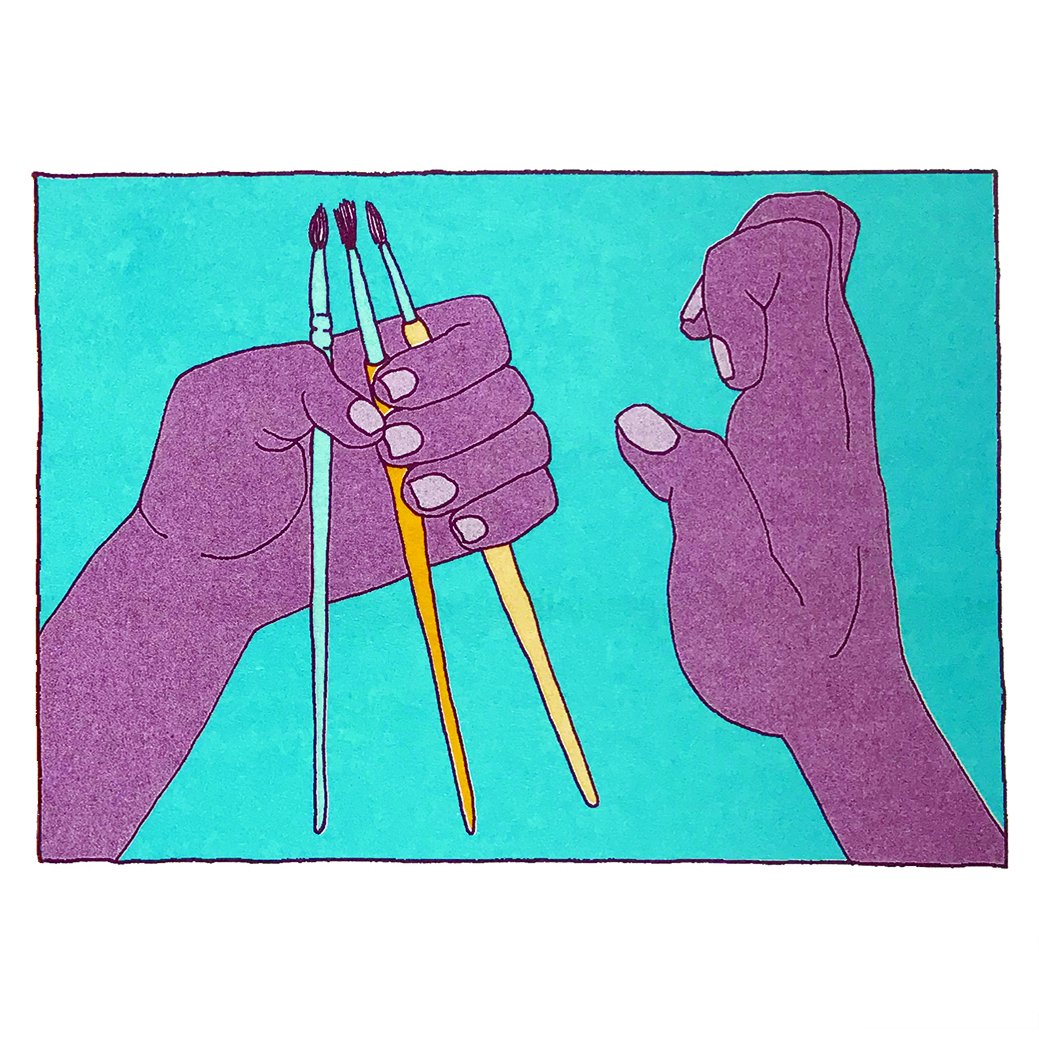

They are the mobs of shadow workers in the art world, the labourers just beyond the frame of established artists and their buyers. Technicians, drivers, personal assistants, carpenters, administrators and jack of all trades. The art world is known to be imprecise and impertinent to equity, where only a small percentage at the top can live securely. The shadow workers are tasked with keeping the motors running in often overworked, underpaid and dizzyingly dysfunctional environments, far from the velvet linings felt by the mega-artists, their managers and collectors.

Andy Warhol famously had his New York factory, a concrete, orotund loft, easily mistakable for a bunker. Assistants, fixed in an assembly line, screen-printed a seemingly never-ending number of images a day. Warhol accrued financial cache while employees fell into drug dependency and depression, as detailed in interviews by his in-house photographer, Billy Name. Similarly, an assistant to the fine art duo Gilbert & George, described how he’d often “paint penises for eight hours a day,” calling it his “daily penance.” As for myself, I would scan and rename hundreds of images for hours on end until my eyes turned red. And that evening, when I logged in the courier’s receipt, a soft rain fell. Not long afterwards, I would be unemployed.

The pandemic has accelerated an already broken job market, not the least of which felt by the art world. It’s been, however, the ongoing BLM protests for the upending of racial order that has amplified widespread interrogations into the workplace. Questions of power and exploitation have been cast: PCS Tate United, a branch of the PCS trade union, led 42 days of strike action in response to the threatened loss of 313 jobs at Tate Enterprises, the gallery’s commercial arm,; art schools such as Glasgow School of Art and UAL called for sweeping managerial changes via Instagram truth accounts. The overwhelming public support for these demands signals a need for new structures as the art world reopens.

Still, shadow workers can often be exempt from modern workplace demands—a convenient, if suspicious mirage shaped in the gloss of the likes of Warhol’s factory, or reframed as positive and flexible work conditions. Martin Sundram, the co-chair of Artists Union England, points out that burgeoning artists “have, or had, employment across the visual arts industry in roles distinct from their own practice as a means to subsist and support their own work.” He says. “My own two first paid jobs after leaving college in the 80s were as an attendant and assistant – representing in those days something of a career path. Then, as now, pay was low and contracts insecure.”

“I would scan and rename hundreds of images for hours on end until my eyes turned red. Not long afterwards, I would be unemployed”

In fact, many of these roles are rarely advertised, and often leapfrog labour laws (in my case, I attempted several times to have a contract implemented—with no success). Sundram, like many others, is certain it has a lot to do with the way the industry is constructed, then contorted over time. “There are various systemic, traditional and inherent reasons why working in the visual arts, or broader cultural industries has, and still does have a high rate of low paid and precarious jobs,” he says. “The obvious one is competition for even the smallest foot in the door of the industry – this is amplified by low paid, but congenial, jobs and, worse, internships, are the preserve of those who are privileged enough to be able to work for little or no pay. Jobs are scarce, sought after and precarious.”

United Voices of the World (UVW), a trade union predominantly focused on organising low-paid migrant workers, noticed that the flat-footed and degrading exploitation of gig workers at Uber and Deliveroo was just as seamlessly implemented in the arts: lack of contracts, vague wage standards, workplace stress and burnouts. So in 2019, they formed a branch dedicated to workers in the creative industry, UVW’s Designers + Cultural Workers (UVW-DCW.) The development was well-timed for the pandemic. Casual workers find solace in workplace security pushed by union efforts.

But, as seen at the Tate Modern, there remains a question mark around the job retention of their most invisible workers, many of whom have already been redundant. Bayryam Bayryamali, a casual worker at the Tate Modern, believes that “the most affected workers facing the burden of the redundancies at the Tate are the catering and retail staff – the lowest paid and most diverse workers alongside cleaners and security.” Bayryamali adds: “[The Tate] will have billions in assets, and some of these assets are paintings by racist artists or depicting racist tropes. They would rather keep these assets than sell them and protect diverse staff. What we need are spaces that care and protect the low wage staff.” The throughline is emboldened, with the most unseen workers bearing the harshest misfortune. It doubles as a warning for things to come.

Shadow workers are invisible only in the way that workers in service of art world-building must be. They further the illusion that artists are atomised, talented individuals, unbeholden to a wider community. The neglect felt by workers is but a justified means to the greater production of valuable art. Without making explicit mention of the craftsmen rigging the machinery, the workers can be doomed to permanent precarity.

“The neglect felt by workers is but a justified means to the greater production of valuable art”

The trouble is how to foster a relationship beneficial to all. Many write off the classic tension between artists and their workers as oedipal resentfulness wrapped in pathology. But it is more evident of a power imbalance only hardened by unstable work. UVW has demanded holistic changes, stamping the need for universal basic income and rent freezes from the government. They call on employers to ensure full-salary pay throughout the pandemic, and a necessary elimination of competitiveness and egoism in the arts.

These moves, both economic and cultural, can reposition shadow workers as not only protected, but valued. If this shift were to take place, when Damien Hirst speaks to The Guardian about how much he has been enjoying lockdown, working on painting cherry blossoms in blissful silence, your first thought wouldn’t be, “Are his assistants doing okay?”