Sex. The delicious guilty tender cruelty of it. Secret (or not so secret) desires bursting from some half-remembered dream avenue, only navigable by a flimsy, sodden map. Nerve-endings standing on their own tippy-toes as your eyes lock together across a crowded room. The taste, the touch, the kiss, the strip. The ecstatic dance and the sickness unto little death – the sweet dumb gelatinous vertigo of delight, like when you put too much sugar in a cup of tea or coffee and it doesn’t dissolve entirely and it pools at the bottom of the mug and you guzzle it up like the dog you are. That’s the sacred flaming fantasy version. Reality is something else.

Paulina Olowska’s ‘Visual Persuasion’ brings her own work into dialogue with twenty-two artists from the Foundation’s collection and six other collaborators, taking over the entire museum space in the process. That includes not just the main, project, and back rooms, but the entrance, corridor, bookshop, technical room, and the cafeteria with its silvery chrome furniture. ‘Visual Persuasion’ is, thus, not simply a reflection of how just about everything in late bourgeois societies has been thoroughly sexualised, but a celebratory – if not entirely uncritical – product of that situation. Instead of taking part in contemporary feminist debates about this issue, Olowska’s response is to focus on the silken surfaces of pleasure, embracing the contradictions of a gooey, vaguely hedonistic ice cream sundae flavour of sex-positivity, showing how even the unsexiest places – like the technical room with its functional metal shelves and electrical equipment – can be part of the landscape of desire.

Olowska considers how the relationship between manual, artistic, and sexual labour, made unstable by changing social and cultural conditions, produces different sexual personae. Even if she doesn’t refer to or draw from the insights of the feminist ‘sex wars’ of the 1980s, in which figures like Andrea Dworkin and Gayle Rubin argued over the social harms or benefits of BDSM, pornography, and sex work, and other issues, Olowska’s work and attitudes can’t help but be at least implicitly shaped by them. In seemingly coming out on the pro-sex, pro-BDSM, pro-porn side, she thus presents us with a huge cast: serenely indifferent femmes fatales, as in in her Seductress (2020) in the cafeteria; sultry posers or weeping morbid starlets in The Time of Culture (2014) and hollow, dead-eyed mannequins mistaken for models in Thomas Hirschhorn’s Ingrowth (2009) in the main room; demons, succubae, primly upstanding bourgeois citizens, and the hustlers, ‘whores’, and pornstars they despise everywhere.

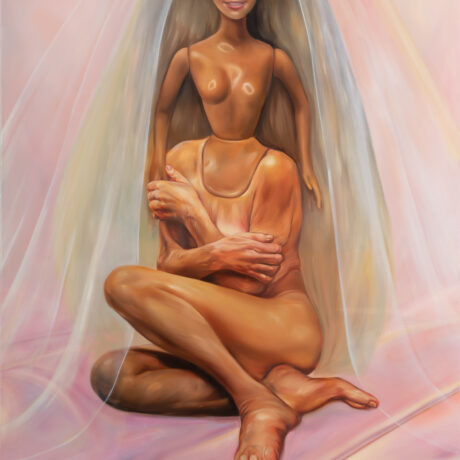

Sometimes this is direct, as in Seductress, in which a woman looks out of the picture plane instead of engaging with the male suitor who is trying to woo her, or Sylvère Lotringer’s Violentes femmes (1998), a twenty-eight-minute analogue video documenting a conversation between legendary Parisian dominatrix Catherine Robbe-Grillet (mostly unseen, her back to the camera) and younger American protégé Mademoiselle Victoria. Or it simply permeates other works, giving them their atmosphere. It’s there indirectly, by implication, in Olowska’s luscious paintings of the mingling swirl of coupled bodies in Spider Painters (2020) or Embrace 2 (2023). And it’s there by way of a chain of references in the three videos that make up Naughty Nymphs in the Courtyard of the Favourites (2022). Here, the artist dances around neo-classical sculptures to the sound of a song from the erotic film Emmanuelle (1974), whose theatrical poster – showing the titular character (Sylvia Kristel) seated, breasts out loud and proud, with one leg in knee-high socks propped up on another, unflinchingly meeting the viewer’s gaze, ready to pounce if she feels like it – Olowska appropriates in Loveress (2020).

In some cases, however, this takes a back seat, as in the four works the viewer sees at the entrance as soon as they enter, which foreground women’s manual labour. Olowska’s The Tychy Plant (2013) is an oil and collage work showing two smiling Polish women workers in a factory constructing a Polski Fiat 126p, a very small, low-price version of the original Italian model, reluctantly endorsed by the Polish United Workers’ Party (the communist party which ran Poland as a one-party state from 1948-89). We see an example of the car in Simon Starling’s Flaga (1972-2000) (2002), a red and white Fiat 126, installed on top of a wall bearing Olowska’s wallpaper piece Tychy-Torino (2023), which shows twenty-four versions of the image from The Tychy Plant. Just beneath it we see Richard Wentworth’s Balcone (1991), a green desk with farm tools (rakes, spades, hoes, brooms) sticking out of it, as if they were ready for use or trophies of work.

Elsewhere, Olowska deals with how desire is ordered, shaped, prepared. Even if they aren’t all in the same room as each other, we see this in the relationship between the rigid construction of Spellshells (2023) in the bookshop, which consists of rows of cabinet like structures like cave-dwellings set into the wall, each one containing a ceramic shell with an implicitly or explicitly vulvic shape which have photographs from glamour and pornographic magazines inserted into them, and the highly organised BDSM practices we hear about in Violentes femmes – the commands and cruel indignities they visit on the willing men they dominate. The Time of Culture, a collage of black and white images from porn and glamour magazines, and Sylvie Fleury’s Chanel fall-winter 94/95 (1994), a pink carpet featuring scattered magazines, both in the main room with Violent Femmes, meanwhile, show us a darker kind of chaos: the sheer thinness of the gap between explicitly sexual material and our ideas about beauty, ‘hotness’, seduction, desire, informed in so many ways as much by porn as by more ‘respectable’ types of glamour.

The entrance, containing The Tychy Plant, Starling’s Flaga (1972-2000), and Wentworth’s Balcone locates part of this problem, and some small amount of resistance to it, in a message of nostalgic solidarity between Turin and the Poland of Olowska’s youth. But there’s also a secret complicitly between these images of labour and consumption and those of Spellshells, Violentes femmes, The Time of Culture, and Chanel fall-winter 94/95 in the main room. They represent different types of factory, different expressions of industrial production: consumer goods on the one hand, the labour of sexuality – whether you’re a glamorous fashion model or bored housewife reading fashion magazines with a glass of red wine at 3PM on a Tuesday – on the other. Both require different types of bodily discipline, it’s just that the women in The Tychy Plant are merely selling their labour (and, yes, party loyalty) for a certain number of hours per day, whereas the models in The Time of Culture and Chanel fall-winter 94/95 are also selling their fleeting youth, beauty, their bone-structure, lips, their whole ‘look’, and a part of their interior lives with it.

Turin is, of course, home of the famous car factory (literally a factory as opposed to the metaphorical factory of the glamour and sex ‘industries’) in the spiral-shaped Lingotto building where the Fiat 126 was designed, constructed, and tested. Between 1973-2000, meanwhile, over three million units of the Fiat 126p, nicknamed maluch (‘the small one’, or ‘small child’), were made in the state-owned Fabyka Samochodów Małolitrażowych in the town of Tychy, twelve miles south of Katowice. This was the first really popular and affordable family car in Poland, where the Workers’ Party weren’t happy with the idea of private car ownership.

The point is not that we know with hindsight that state socialism failed and the factory was privatised in 1992. It is, rather, that not only were very basic kinds of pleasure possible under even these conditions of dutiful obedience, but that pleasure in late capitalist societies is just as organised, requiring just as much compliance, only under market conditions: the sex and glamour we see in The Time of Culture and Chanel fall-winter 94/95 is a scarce commodity, promised but always withheld. These works thus have more in common with Wentworth’s Balcone than we might expect. The desk may remind us of the forbidding bureaucracy of the planned economy; the farm tools, the repressive world of the peasantry. Both represent the imperatives of a system, communist or capitalist, based on conformity of behaviour and desire.

The kind of sexualised labour we see in The Time of Culture and Chanel fall-winter 94/95 appears, however, in a glaringly obvious and concentrated way in the neon signs in the corridor and the relationship between Olowska’s works and those by Sarah Lucas, Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Maja Berezowska, and Berlinde de Bruyckere in the project room.

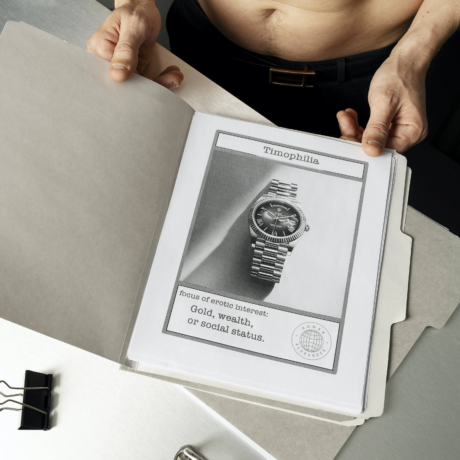

Even if ‘Visual Persuasion’ has limited political stakes, these works give us an important sense of two categories: the internalisation of the piercing male gaze and the fragmentary idea of the body to which it contributes. This is underscored by the source of the exhibition’s title – advertising executive Stephen Baker’s 1961 book of the same name, which details how advertisers can use various strategies of suggestion borrowed from psychoanalysis (which was becoming increasingly respectable and institutionalised in the United States at the time) to stimulate their customers’ unconscious desires.

One chapter deals with sex in advertising, which Baker says has to steer between two competing social demands about which the consumer is always aware. On the one hand, the conflict between lingering puritanical social attitudes about sex and its collision with commercial and entertainment culture, which constantly circulate stimulating images of half-naked women. On the other hand, there are consumers’ explicitly gendered desires about what can be sold to them when advertising is sexualised: rough-hewn cavalier adventurousness for men, and elegant, atmospheric fantasies about emotions that go beyond sex for women. Olowska even seems to embrace some of this, though this is more obviously the case in the corridor than the project room.

Here, Olowska covers the walls of the corridor with neon signs, in which the ambivalent relationship between commercial glamour, seedy sexuality, and art history is on full display. This begins with Sylvie Fleury’s Egoïste (1996) and then runs through the seven that make up Olowska’s Visual Persuasion (2023), reading ‘Amour’, ‘Tintoria Crocetta’, ‘Le Select’, ‘Video Club’, ‘Casa del Materasso’, ‘Voyage Montparnasse’, and ‘Redhead Piano Bar’.

The mixture of direct exhortations to love and sex (‘Amour’), references to places that might eventually lead to sex (a piano bar, romantic Paris), and private pleasures that we tend to hide away (‘Video Club’), alongside other kinds of commercial ventures, is another example of the close relationship between sexual and other types of affective labour in consumer society (waiting tables, retail, etc) and the embrace of commercial imagery since at least early experiments with collage. This prepares us for the works in the project room, which allow us to identify a basic fissure that makes sense of ‘Visual Persuasion’: that between the male gaze itself, how women internalise it, and the confusion this produces in our wider cultural assumptions about sex which can, by reading Berlinde de Bruyckere’s wax, wood, and glass sculpture La Femme Sans Tête (2004), at least partially be traced back to the birth of the whole discipline of art history in Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s description of The Belvedere Torso (circa1st century BC).

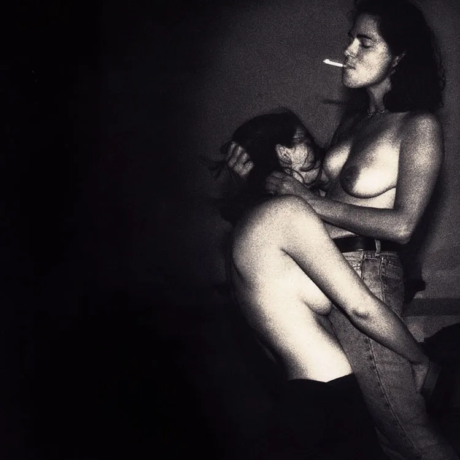

The project room contains three works by Olowska: A Bit Pale, Drowning, Silver Foam, and Embrace (all 2018), full, like Spider Painters and Embrace 2, with bodies melting into each other in secret acts of joy. They’re shown alongside Sarah Lucas’s Nice Tits (2011), two examples from Cindy Sherman’s series ‘Untitled Film Still’ (1980), Nan Goldin’s Joey on my roof, NYC (1991). Especially important, however, are Maja Berezowska’s collection of untitled drawings on paper (1965-70) and Berlinde de Bruyckere’s La Femme Sans Tête, a ruined female body lacking a head, perhaps modelled as much on The Belvedere Torso as it is on her childhood interest in Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Nice Tits, shows us a strange collection of breasts made from nylon tights bursting like sacks of potatoes – or even dead moles from some wretched collection of zoological curiosities – from a metal net with a pair of concrete legs wearing thigh-high boots standing on a plinth. This grossly exaggerates the significance of individual parts of women’s bodies, but the same principle is on display in Joey on my roof, NYC, which shows a woman from behind, emphasising her backside, her legs, her back. The same is true for Maya Berezowska’s drawings. The latter, in particular are not just about the male gaze: the mere objectification of women’s bodies in films and images in ways that perpetuate patriarchal forms of social organisation.

They emphasise, rather, how women have internalised it. Not only do male standards delineate and dictate, or simply assume outright, what kinds of things women can or should find erotic, perpetuating the male gaze by circulating these kinds of images, allowing them to flourish as they become dominant industry standards, models as rigidly determined as the car we see being made in Olowska’s The Tychy Plant that go on to shape how almost all images are made and looked at. The issue in Olowska’s use of Berezowska’s work in this context is how women may have adopted these standards for themselves.

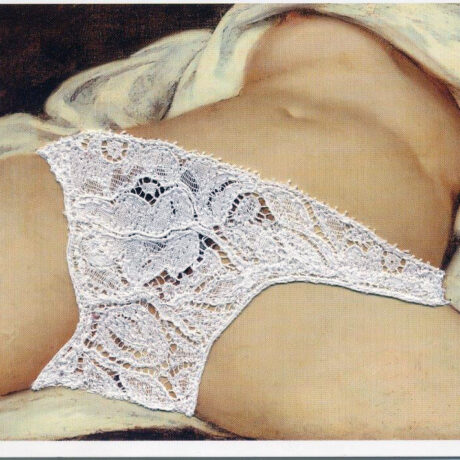

This finds its most concentrated expression in de Bruyckere’s Femme Sans Tête due to its deep cultural-historical resonance. An incomplete, contorted, headless woman’s body shows us what is most at stake in ‘Visual Persuasion’. The issue is not just the wealth of sexualised images that are out there. It’s in how the concepts of beauty that we operate with, whether in the high concepts of philosophical aesthetics or the prosaic decisions about how fashion images or pornographic scenes are framed or edited, are ultimately derived from an idealised idea of fragmentation that lends support to how women – all of us, really – take a fragmentary view on ourselves by internalising the male gaze.

In his ‘Description of the Torso in the Belvedere in Rome’(1759) Winckelmann extols the virtue of the fractured, ruined sculpture of Hercules. This contains, according to Winckelmann, an idealised kind of beauty. The statue is broken, irrepadable. So the beauty is not present to us. We are only left to imagine it. In taking fragmentation as his standard of beauty, Winckelmann claims that the greatest virtue of the statue is in what it lacks. This is a condition that is explicitly denied real women as much as it is those idealised goddesses and nymphs we see in fashion photography, corroding our sense of ourselves and others as erotic creatures. This is, at least partially, because this whole problem – inherited by feminist thought – runs through the history of western thought on art, from Kant’s claim that beauty is ‘without a concept’ to the sinister problem Audre Lorde recognised in pornography. The latter is especially relevant for understanding Olowska’s exhibition. Porn is, Lorde said, merely ‘sensation without feeling’.

Words by Max Feldman