“The conveying of information is about the transmission of sound. It’s dynamic and ever-evolving: we’re constantly discovering new perspectives and truths…” Listening to Peter Adjaye is an engaging experience. The Ghanaian British conceptual sound artist, musicologist, DJ and musician never just seems attuned to his surroundings, he is somehow symbiotically connected with them, and his expressions can carry you into unexpected spaces.

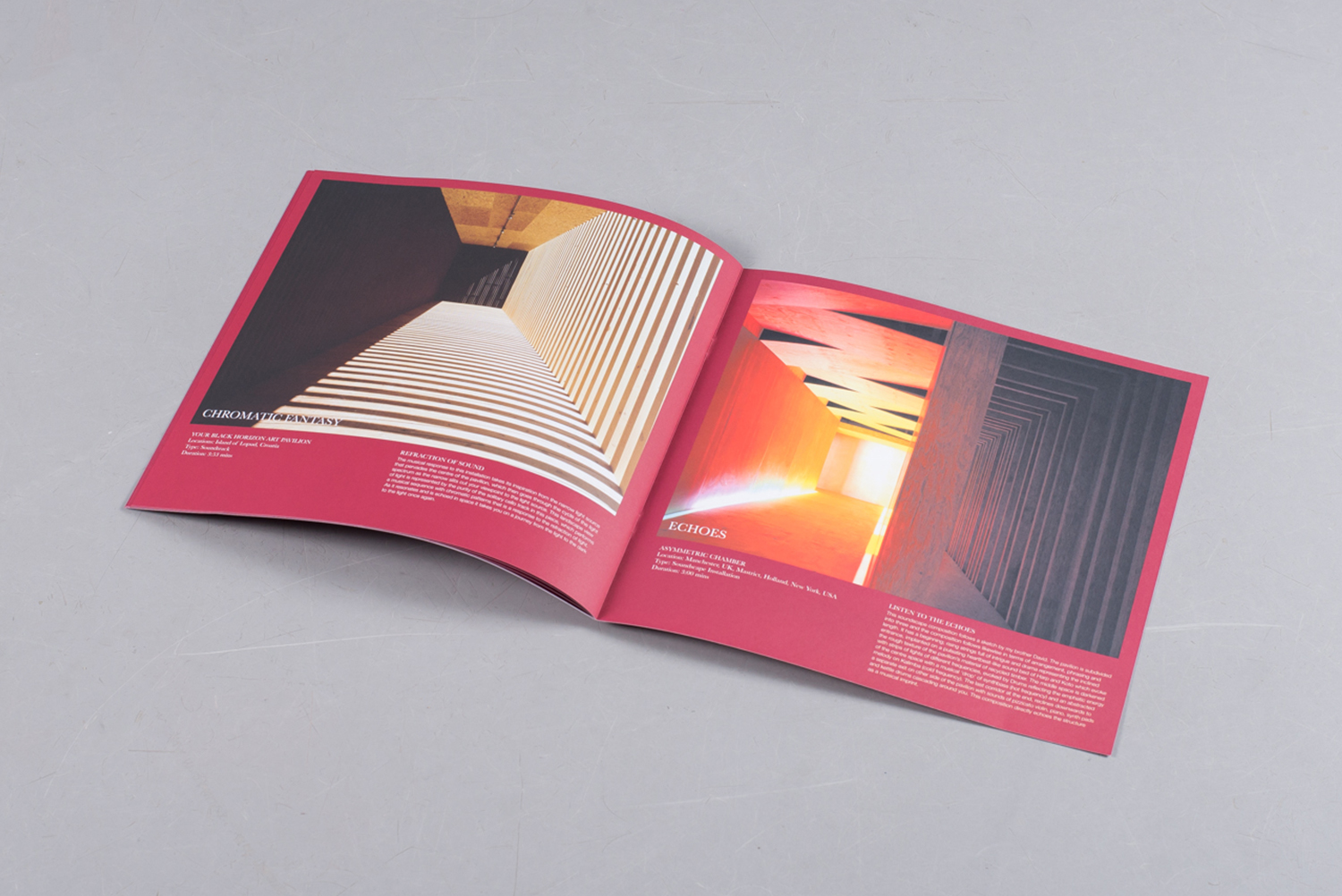

Before now, my chats with Adjaye have always taken place at club nights and gig venues, including the celebrated Afri-Kokoa parties he ran across London (under his DJ guise, AJ Kwame). He’d converse animatedly about music, culture, family and geography, while highlife rhythms or electronic beats pulsed around us. There’s still a clubby energy to his international projects, such as his Music For Architecture project with his brother, renowned architect David Adjaye, which yielded a gorgeous 2016 vinyl-only LP, Dialogues. It comprised soundtracks composed by Peter for buildings designed by David’s studio, from London’s Stephen Lawrence Centre to Oslo’s Nobel Peace Centre. “Architecture is an encasing for sound,” smiles Adjaye. “It sculpts the air, separating it into these different volumes.”

More recently, Adjaye’s widely acclaimed collaboration with Nigerian American visual artist Toyin Ojih Odutola, A Countervailing Theory (2020), conjured intricate mythological landscapes within the Barbican’s brutalist Curve Gallery. The show has just moved to the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Denmark and will continue to Washington’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. While Ojih Odutola’s lucid, large-scale drawings depict an imagined ancient civilisation dominated by women, Adjaye’s immersive composition intensifies the narrative, layering roots instruments (inspired by Nigeria’s Jos Plateau region) with strings, brass and electronics.

“I try to have a purpose for sound. It might not begin with a visual, but it certainly has a narrative behind it”

Adjaye describes this composition, entitled Ceremonies Within, as “soundscapes overlapping with infinite possibilities—three movements, creating pockets of interaction and introspection, which allow you to pick your own ‘viewing ledge’…to be inside this place.”

Adjaye’s work feels like a meditation on his personal experience as “an African boy who’s lived all over the world, and is honestly fascinated by all cultures”. Born in Kampala, Uganda to Ghanaian parents, his father’s work meant a peripatetic upbringing, including a stint in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where he recalls the daily prayer calls, but also the vivid cacophony of the outside world behind the high walls of their home.

“I became very aware of the contrasts in sound between these different environments,” he says. “There was that really interesting clash of the cultural modern sounds of a newly formed capital city in Africa or the Middle East—motorways and traffic, oil tankers, vast industrialisation—contrasting with really traditional living, the sounds of prayers, weddings, celebrations and commemorations. Sound seemed to be such an important part of human connection.”

Adjaye adds that both he and his older brothers James (now a Dusseldorf-based doctor) and David were obviously affected and inspired by their youngest sibling Emmanuel, who contracted an infection as an infant which impacted him mentally and physically. “Sound was really important, because Emmanuel’s epilepsy was triggered by sudden or loud sounds,” says Adjaye. “We had to be really careful how we moved around the house. I absorbed it into a deep connection with every aspect of sound. I’m hyper-alert to murmurs, the background is sometimes more hyperreal than the foreground, and the visceral power of sound comes out in my work.”

Adjaye’s family moved to London in the “crazy hot summer” of 1977. By his mid-teens, he was a music and tech obsessive, teaching himself to play instruments as well as code the rudimentary home computer (a 3.5K Commodore Vic20) he had bought with his paper-round money.

While studying mathematical engineering at Sussex University, Adjaye would also play bass in a Brighton jazz band, share a gig bill with Gil Scott-Heron, establish his DJ career, and later sign to UK label Mo’ Wax. His intuitive embrace of analogue and digital, and his fascination with overlapping histories and disciplines, resonates through his art. “I try to have a purpose for sound,” he says. “It might not necessarily begin with a visual, but it certainly has a narrative behind it.”

Emphatic, empathetic narratives unfurl within Adjaye’s latest works, including his collaboration with Ghanaian-British artist Adelaide Damoah, as part of the group show A History Untold at London’s Signature African Art Gallery. Their six-speaker sound/sculpture installation explores colonialism, their relatives’ involvement in WWII (as Ghanaian fighters in the Gold Coast army), and the erasure of such input into the British efforts.

“Architecture is an encasing for sound. It sculpts the air, separating it into these different volumes”

“The idea is to have an ‘acoustic mist’, with sound at a certain level: on the ground, but encroaching on a sculpture that Adelaide is making,” explains Adjaye. “It features a recording of her great-uncle talking about his role in the war, his stories of being kidnapped, in our language, Twi, creating a sonic landscape where this story takes place. It’s not static, the sound moves, builds and crescendos through many cinematic dimensions, with references to culturally important Ghanaian rhythms and instrumentations, but also, as per a lot of my practice, a lot of orchestral strings, synthesizers. I want you to feel like you’ve gone through something, then come out of it.”

There is also a dynamic, revelatory quality to another new work, within London’s Chiswick House and gardens .“I’m working with Southern Asian and West African musicians on a response to the architectural and historical aspects of this 18th-century English Heritage home,” says Adjaye. “Its designer, Lord Burlington, had this eye for ancient art. They’ll talk about the references to Italian Palladian architecture, but it’s like: ‘Hold on, what about those obelisks, that sphinx over there?’ The architectural aspects link back to the Greeks, then back to the Egyptians. It’s all borrowed cultures, but we erase where it came from.”

Adjaye’s ambitious three-part audio artwork takes the “transhistorical” perspective that he also applied to his 2020 sound installation at London’s Queen’s House, which responded to the Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I and its legacy of empire. At Chiswick House, he again assembles a disparate array of musicians (including Senegalese kora player Jali Fily Cissokho, Jonathan Mayer on sitar and tampura, and South Indian vocalist Rekha Sawhney), and creates classical work that challenges Eurocentric conventions.

“I’m working on a response to this 18th-century home…It’s all borrowed cultures, but we erase where it came from”

“My story is called: We Bear The Light Of The Earth In Red, Green, Black And Brown,” says Adjaye. “I’ve chosen the incredibly ornate Red and Green Velvet Rooms, and other cues in less obvious parts of the building. I’d written what I call a composition of improvisational technique: as soon as the musicians heard my soundscape in the space, we were recording it. I’m interested in the direct emotional response. The sound is allowed to breathe and develop its character through open doors.”

Two further compositions, Sunrise Of Invisible Gold, and Sunset In Rippling Bronze, are presented via QR codes at the garden’s entrance and their central Obelisk and Ionic Temple, reflecting connections—sonically, physically, philosophically—to Africa and Asia. “I try to make work that’s connective,” says Adjaye. “The intimacy is really important, the collaboration has always been personal. My work is always about a dialogue, and there’s a definite sharing of secrets.”