Marlee Miller, an academic who specialises in gladiators, returns to provide context and commentary on the historical and artistic motifs that shape Ridley Scott’s epic sequel, Gladiator II.

Gladiator II has finally hit theatres, and it piles spectacle on spectacle! Set during the reign of two brothers, Caracalla and Geta of the Severan Dynasty, the story unfolds 24 years after the events of Gladiator (2000).

Hanno—also known as Lucius, heir to the Roman Empire and son of Lucius Verus and Lucilla—is taken hostage as a prisoner of war after Roman forces conquer his city in North Africa. This was common practice at the time; many prisoners of war and criminals were captured and sold for use in the arena, either as fighters or as bait for animals.

Lucius is bought by Macrinus, the owner and manager of a gladiator troupe, who came from an equestrian family of Berber origin in Caesarea, Algeria. He would later serve under Caracalla as praetorian prefect and eventually conspired to kill him and take his place—unlike the events of the movie. Macrinus ruled only from April 217 to June 218, becoming the first emperor not from the Senatorial class. His reign ended when he was overthrown and killed in favour of the young Elagabalus, an exiled member of the Severan dynasty, who returned the throne to the family. The dynasty ultimately ended in 235 CE with the reign of Emperor Severus Alexander.

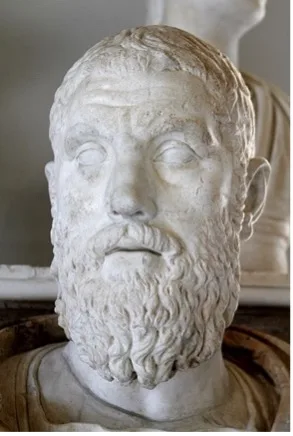

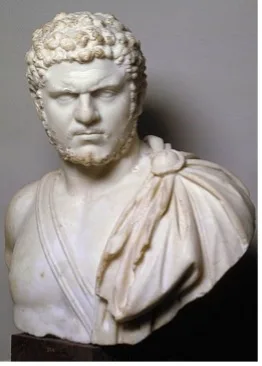

In Rome, we meet the co-emperors Caracalla and Geta, presiding over a triumph and lavishing in their palaces with endless entertainment and feasts. Caracalla and Geta were the sons of Septimius Severus, who ruled from 193 to 211 CE. A military man, Septimius claimed the throne with the support of his troops. Caracalla ruled alongside his father from 198 to 211 CE, and Geta joined their co-rule from 209. After Septimius’ death in 211, the two brothers ruled together briefly until Geta was assassinated.

Septimius Severus was the first emperor from Africa, his hometown being Leptis Magna, a major Carthaginian city incorporated into Roman Libya. Their mother, Domna Julia, served as empress from 193 to 211 and was born in Emesa (modern-day Homs) in the Roman province of Syria. This family would have appeared very different from their depiction in the film. They were not pale—let alone “White,” as understood in the Western tradition—but more reflective of their African and Syrian heritage. A painted tondo of the family confirms this. The Severan and Macrinus families would have looked more similar to one another, given their shared lineage and places of origin, than they do in the film.

This tondo also verifies Caracalla’s hatred for his brother Geta, whom he had assassinated to become sole emperor. Geta’s images and memory were erased by order of Caracalla, a decision later confirmed by the Senate. This practice is now understood through the modern term damnatio memoriae. While the act of damning someone’s memory and erasing them from all records, including art and money, is well-documented in ancient cultures such as Rome and Egypt, the term itself is a modern invention.

The first article in this duology discussed gladiator training, types of armament, and life as a gladiator in more detail, though in Gladiator II, we do see Hanno fighting, or boxing, another gladiator at the training school. The fight was particularly bloody because of the wraps worn; ancient boxing gloves covered far less of a fighter’s hands than our contemporary ones—think of the famous Boxer at Rest bronze sculpture—and may have even incorporated metal, similar to brass knuckles. Only one excavated pair of such gloves has been found at Vindolanda, along Hadrian’s Wall.

Any viewer who took a version of Art History 101 would have recognized the Capitoline Wolf statue, seen over the triumphal arch at the end of the film during Lucius’s fight with Macrinus as the two legions met to decide the fate of Rome. This sculpture has become synonymous with Rome and refers to the story of the city’s founders—another set of brothers, Romulus and Remus, who in this case were twins. Left to die on the Tiber River, they were taken in by a she-wolf (lupa in Latin, which also means prostitute) and later raised by a shepherd named Faustulus. The dating and origin of this sculpture remain subjects of great debate—whether the wolf is ancient or from the Renaissance, and when the babies were added. Anyway, the key takeaway from this discussion is that this statue would not have been placed on the arch or displayed along the road to Rome.

Lastly, a few topics that caught my attention: Macrinus makes a bet with “gold denarii,” a currency that did not exist. Augustus reformed the Roman monetary system, assigning each denomination with its value and material. The gold coin, the aureus, had the highest value, worth 25 denarii or 100 sestertii. The denarius, made of silver, was valued at 4 sestertii, while the sestertius was a copper coin, worth 4 bronze asses.

Macrinus also claims to have read some of Marcus Aurelius’ great work, The Meditations, although that would not have been possible. Written in Koine Greek, these writings, spread across twelve books, were personal reflections and never intended for public consumption; in other words, they were his personal journal. The title Meditations—or in Greek Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν (Ta eis heauton), which translates to “Things Unto Himself”—was given to the work later on; no original title is known to have been given by Aurelius himself. The writings remained undiscovered and unpublished as a manuscript until several centuries after his death, around 900 or 1000 CE, although it had long been recognised that Aurelius was a deep thinker and writer.

And, again, there would not have been sharks in any amphitheatre for naval battles, or naumachia. However, animals from across the empire were brought for arena entertainment, including lions, tigers, rhinos, and bears, and there is evidence of camel remains at the amphitheatre at Viminacium, in Roman province of Moesia in modern-day Serbia.

Written by Marlee Miller