Things look bleak in many parts of the cultural sector. At this time of real fear for the future prospects of workers and organisations, it might seem strange to be discussing inequality. However, the unequal nature of the cultural sector, in terms of consumption and production, has never been more important.

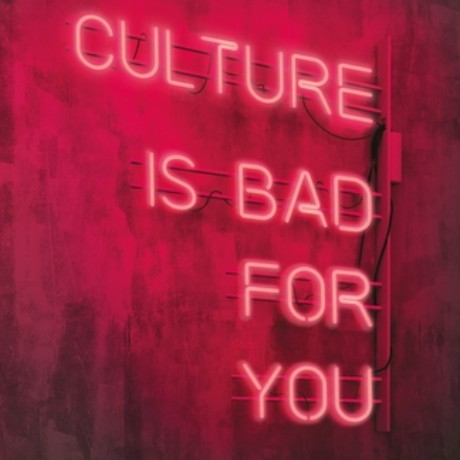

In our new book, Culture is bad for you: Inequality in the Cultural and Creative Industries, Orian Brook, Mark Taylor, and I detail the longstanding inequalities that characterise our cultural industries. These inequalities are not recent developments. Rather, cultural jobs, along with patterns of cultural consumption, have long been exclusionary and unfair.

We used hundreds of interviews with workers in a range of artistic and cultural occupations, along with analysis of secondary datasets from the UK government and from the Office for National Statistics. The research paints a bleak picture. Making a sustainable living in any cultural occupation—for example as a visual artist, a musician, an actor, or a writer—is a difficult task. Yet, it is much more difficult for some than others.

“Cultural jobs, along with patterns of cultural consumption, have long been exclusionary and unfair”

The statistics should, sadly, be familiar. ONS data suggests people of colour constitute just five percent of publishing occupations, a serious issue for equality and diversity in this sector. Film, TV, radio, and photography, and design also have fewer people of colour (nine percent) than we might expect if they were representative of the workforce more generally (13 percent overall).

We see similar problems with gender in cultural and creative occupations. Only music, performing, and visual arts, and museums, galleries, and libraries having more women than men. In Film, TV, radio, and photography (29 percent women), there is clearly a crisis for women, as they are significantly excluded from these occupations. Even in museums, galleries, and libraries (81 percent women) the gender imbalance of the workforce is reversed at the very top of our highest profile institutions, with women still absent from significant numbers of leadership roles.

Social class sits alongside race and gender as a problem for the current cultural and creative workforce. The majority (52 percent) of those working in creative occupations in 2019 were from professional and managerial, ‘middle class’ social origins. This is despite these origins being little over one-third (37 percent) of the total workforce. In contrast, just 16 percent were from working-class backgrounds compared with 21 percent of professional occupations and 29 percent across all occupations.

The class crisis is even more stark in specific cultural occupations. It is persistent over time too, with data from 2014-2019 showing how occupations in Publishing (13 percent from working class origins in 2019), in Music performing and visual arts (12 percent), and Film, TV, video, radio and photography (16 percent) all have medium term exclusions of those from working class origins.

“Barriers to success are complex and they are present long before individuals try to get work in the cultural sector”

Those from privileged backgrounds are overrepresented in specific roles within occupations. In publishing, authors, writers and translators (59 percent), and journalists, newspaper and periodical editors (58 percent); and in film, TV, radio & photography: arts officers, producers and directors (54 percent), are all dominated by those from the most elite social starting points.

Who gets in, and who gets on, in cultural occupations is deeply unequal. Whilst white men from middle class origins may find it hard to ‘make it’ in culture, their struggles are much less demanding than those faced by women, those from working class origins, and people of colour. Indeed, those individuals at the intersection of these broad demographic categories face the highest barriers to their success.

Those barriers to success are complex and they are present long before individuals try to get work in the cultural sector. Barriers to success include the hostility of organisations and institutions who do not see people as legitimate visitors, customers, or audience members; unequal experiences of low- or no-pay jobs and internships; and commissioners, funding bodies, and employers who see those who are not white, middle class origin, men as a ‘risk’.

This latter point is perhaps the most depressing thing we found during our analysis. The cultural sector is attached to ideas of innovation and novelty, as well as to the importance of talent and skill. At the same time, who is seen as innovative and novel, who is seen as talented, has a predictable pattern. White, middle class men are most likely to benefit from assumptions about what audiences want, or what innovation and talent are.

“Those from privileged backgrounds are overrepresented in specific roles within publishing, journalism and film”

Those who do not fit this narrow version of the artist, the musician, or the writer, are deemed too ‘risky’. Commissioners wonder if there will be a market or audience for their creative activity, employers say they are taking the ‘sure bet’ or ‘safe option’. Both of these ideas, about risk and safety, are not only incorrect about the levels of market and audience demand, and about individual’s talents. They also reduce what it means to be an artist, a musician, a writer, to a narrow norm of a white, middle class origin, man.

The sociologist Nirmal Puwar has described this ‘somatic norm’ in other institutions at the centre of British life. In her work, this idea of a somatic norm helped to explain why the senior ranks of the British state were dominated by that narrow, white middle class origin male, norm. It also helps to explain some of the statistics on inequality we document in the book.

A cultural sector where white, male, middle classness is an unwritten norm can never represent contemporary Britain. In light of these structural inequalities we really do need, to quote the current government slogan, to build back better. Building back to where the sector was will mean continued exploitation and exclusion. Culture really will be bad for us all if the ambition is only to recreate the dominance of the white, middle class man.

Culture is bad for you: Inequality in the cultural and creative industries

Out now with Manchester University Press

VISIT WEBSITE