The nude is the most revisited subject in art history, from the classical era to contemporary. It’s obsessed us for centuries, and it’s not only to do with sex: a good nude, painted, photographed or performed, has always had something more to say. Photography is the most innovative medium, and an arbiter of change and witness of time. At a commercial fair, like Paris Photo—which opens today and runs until Sunday under the spectacular glass roof of the Grand Palais—nudes proliferate, as you might expect.

Modigliani’s Nu Couche became the most expensive painting Sotheby’s ever sold last year at auction, fetching 157.2 million USD. Alfred Stieglitz’s nude portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe didn’t fetch quite that, but the 1919 photograph reached $1,360,000 at a 2006 auction, while Edward Weston’s modernist photographic study, Nude (1936) sold of $1,609,000 when it last came up for sale. The model is Charis Wilson, Weston’s long-time muse, assistant and, later, his wife.

But tastes are changing, and that’s evident when it comes to bodies. At Paris Photo there is plenty of proof that we don’t have to keep hammering the same ideas of what makes a beautiful nude image. Sure, there are plenty of examples of the traditional stuff—headless, supple-bodied female nudes, athletically posed; conventions established first by male painters and then photographers. But there are also nudes that disrupt and disturb; they move away from what bodies can do, and what they can signify.

“Dora Maar nods to the surrealist interest in nudity as an expression of the unconscious, but she also makes it playful”

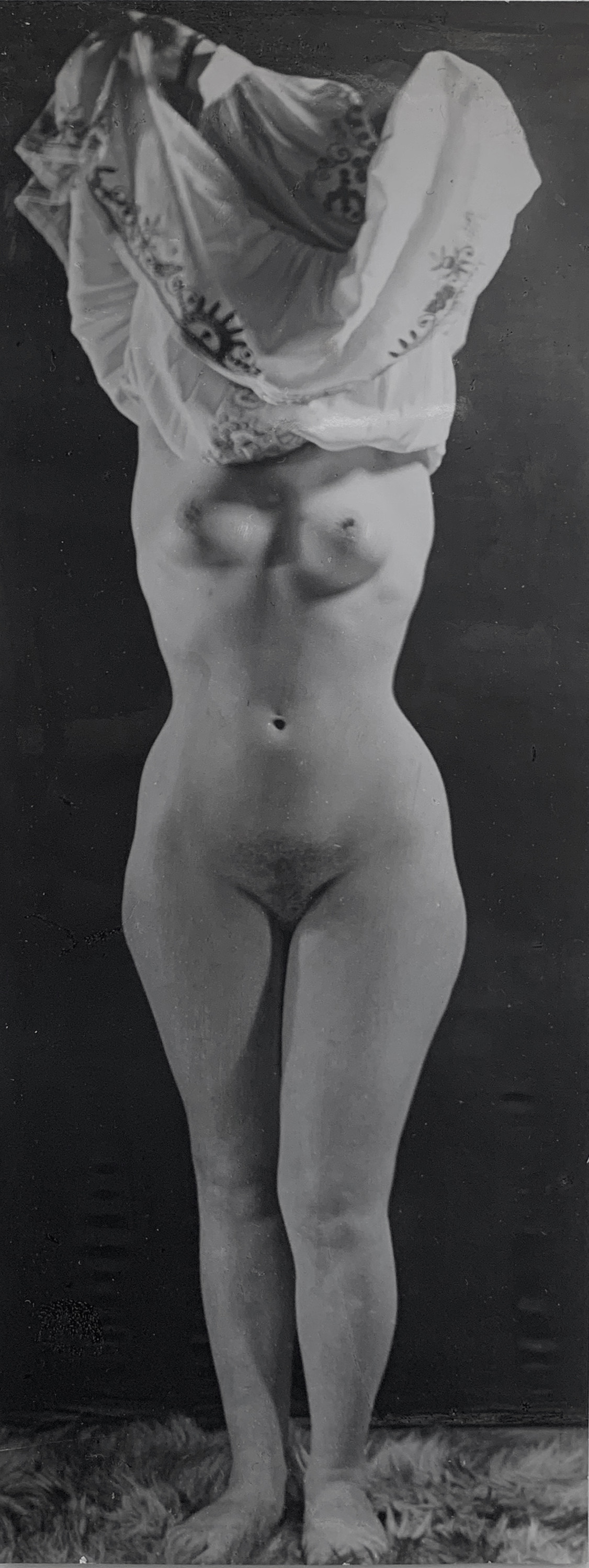

Paris Photo has always excelled at presenting the whole breadth of the history of photography, and when it comes to nudes, it’s important to revise the idea that nudes only interested male artists. At James Hyman’s booth is a vintage print of a photograph of a female nude taking off her robe, taken in 1943 by Dora Maar—the groundbreaking surrealist who will have a long-overdue retrospective at the Tate Modern from 20 November 2019. It is early female-gaze magic: from the furry rug she stands on to the fluidity of the lines that move from the dress tangled above her head to down her body; Maar still nods to the surrealist interest in nudity as an expression of the unconscious, but she also makes it playful.

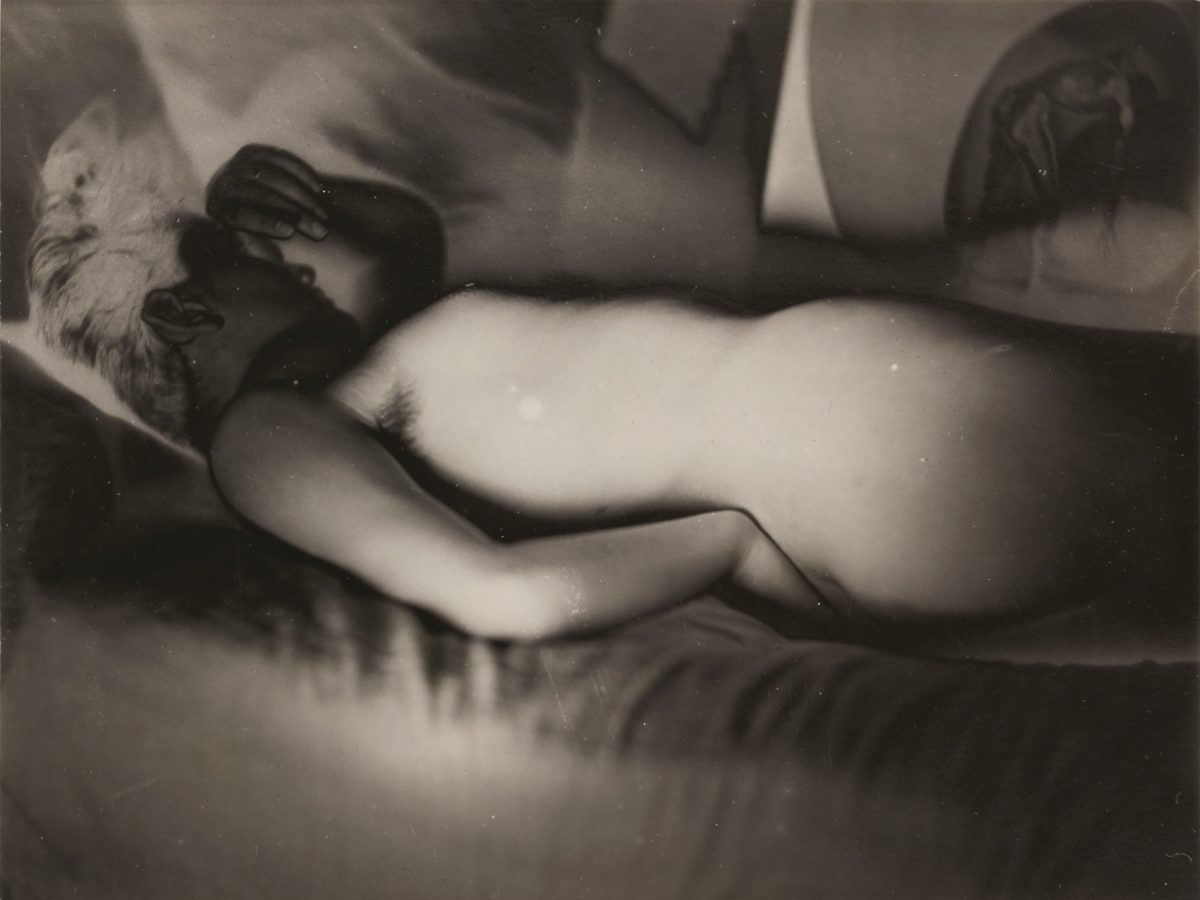

The politics of the nude remain, especially when an older man photographs a younger woman. At Gagosian

’s booth there is a portrait of a nineteen-year-old Meret Oppenheim; taken in 1933 by a forty-three-year old Man Ray, a dynamic that certainly should raise eyebrows. Oppenheim does not return the gaze and appears unattainable, both physically and intellectually—from us and from the photographer. The nude picture was among many Ray shot that year for his Erotique Violee, the only nudes at that point in time that had shown nipples and body hair—in this portrait, Oppenheim’s armpit hair is clearly visible, and now looks remarkably contemporary. The tension in Oppenheim’s pose seems to emanate as much from her as from Ray’s gaze on her—her refusal to return it seems to be an implicit statement.

“The politics of the nude remain, especially when an older man photographs a younger woman”

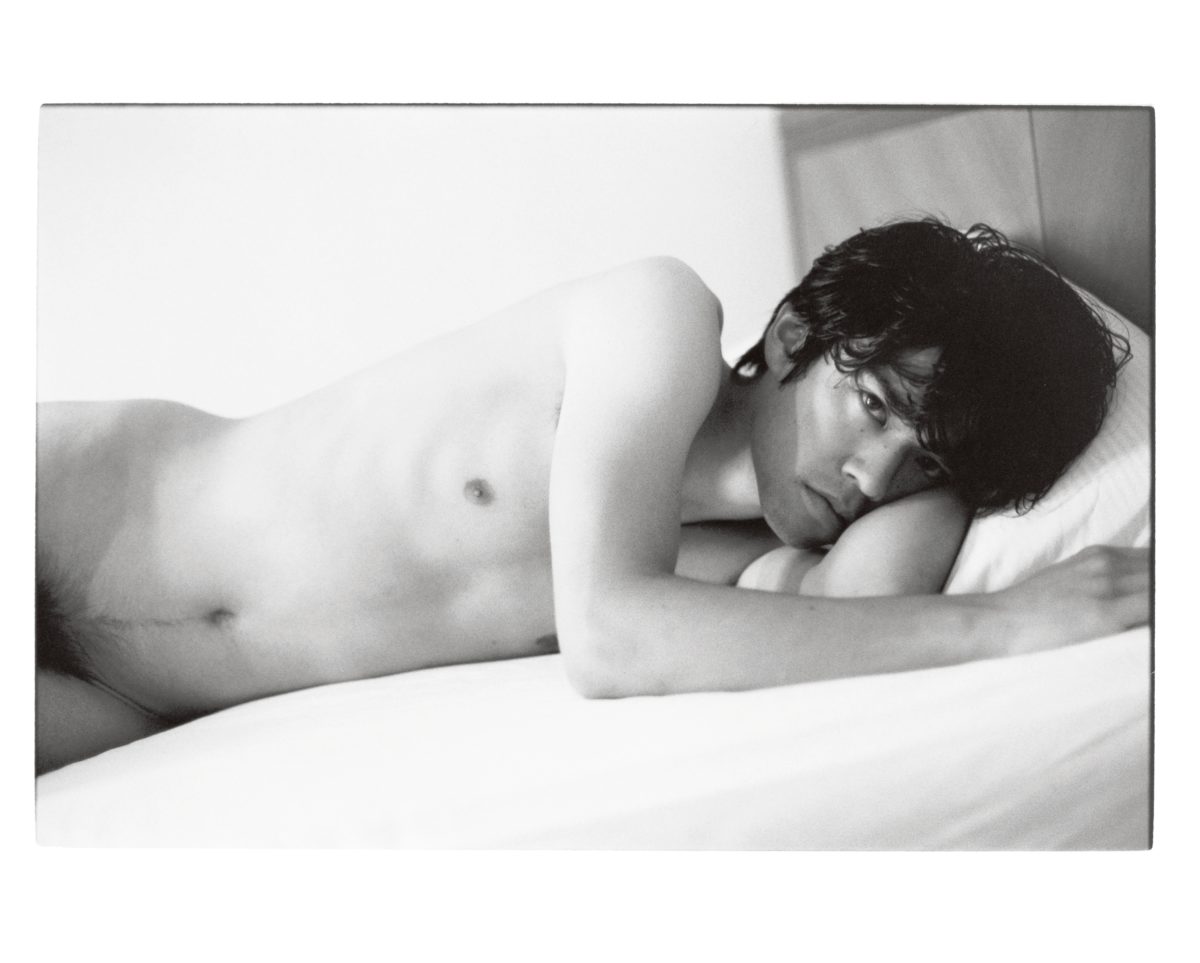

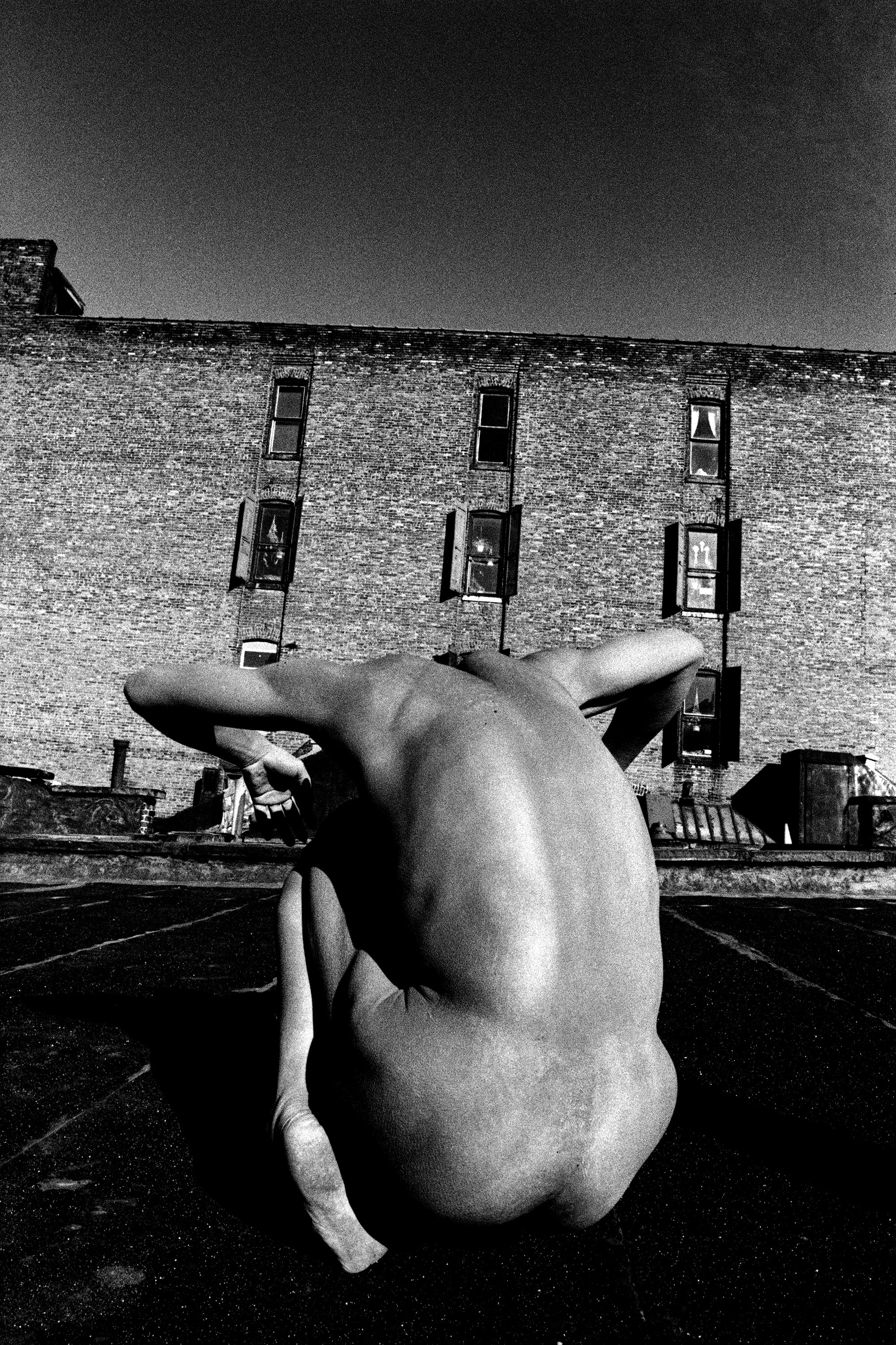

More contemporary examples introduce the male nude in photography as rich and unexplored terrain, no matter the gender of who is behind the camera. Keiichi Tahara’s 1978-1980 large-format portraits of the legendary dancer Min Tanaka, Photosynthesis, explore the interactions between the male figure and the light. The body is shot against the urban environments of Paris, New York, Rome and Tokyo, focusing on what Tahara referred to as the “pivotal moment where meditations on physical light met the art form of the human body.” A series of the Photosynthesis works is showing at Yoshiaki Inoue’s booth at the fair.

One of the most recent nudes is a black and white nude by Melanie Schiff; Lay (2018), presented by Louise Alexander and on sale for $6000, is one of the American artist’s more recent explorations. At first it appears to follow the tropes of a typical classic nude, with a still, reclining female figure, faceless and poised. But, on closer inspection, the self-portrait—presented at Schiff’s 2018 exhibition Lay, Lie, Lay—examines the gaze we have on our own bodies, the nostalgia, self-enquiry, and desire that can ignite. Perhaps what keeps artists and spectators returning to the nude is exactly this: the impulse to see some truth about ourselves reflected back.