In her new column, Reading Out Loud, Elephant’s associate editor Emily Burke asks an artist for a book recommendation and then, after reading it herself, sits down to discuss it with them. In her first article of the series, Emily meets with Chloe Wise to talk about aliens and the limitations of human understanding inspired by their shared reading of Diane Walsh Pasulka’s ‘American Cosmic’.

I meet Chloe Wise at Almine Rech in Brussels, the day before the opening of her show Torn Clean. I’ve been awake since 5.30 a.m. and I’m wearing a pair of seriously impractical heels that I’ve been walking across Brussels in for the past hour. I make a mental note to buy a plaster on the way home and hope I’m not trailing blood through Almine Rech.

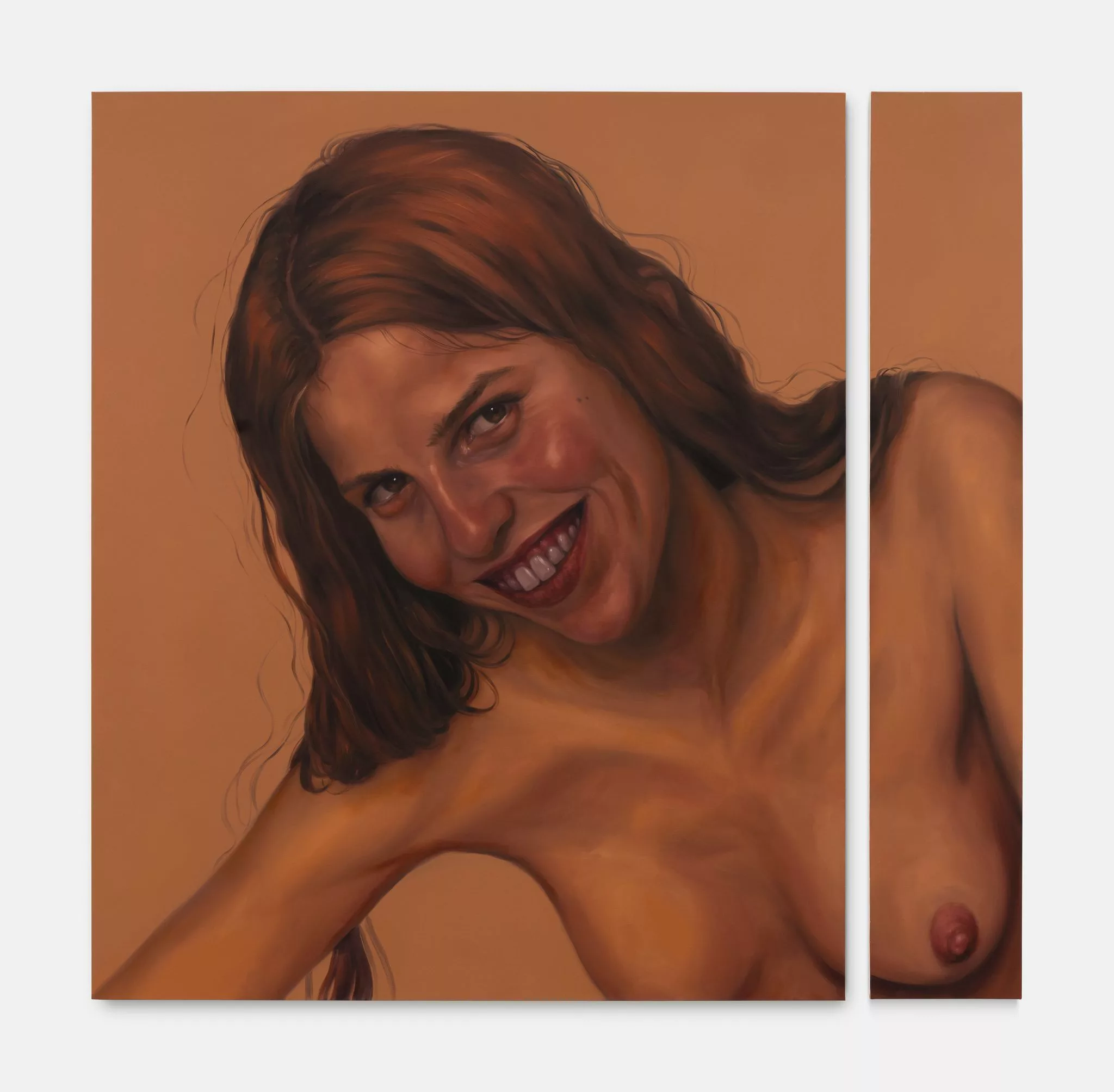

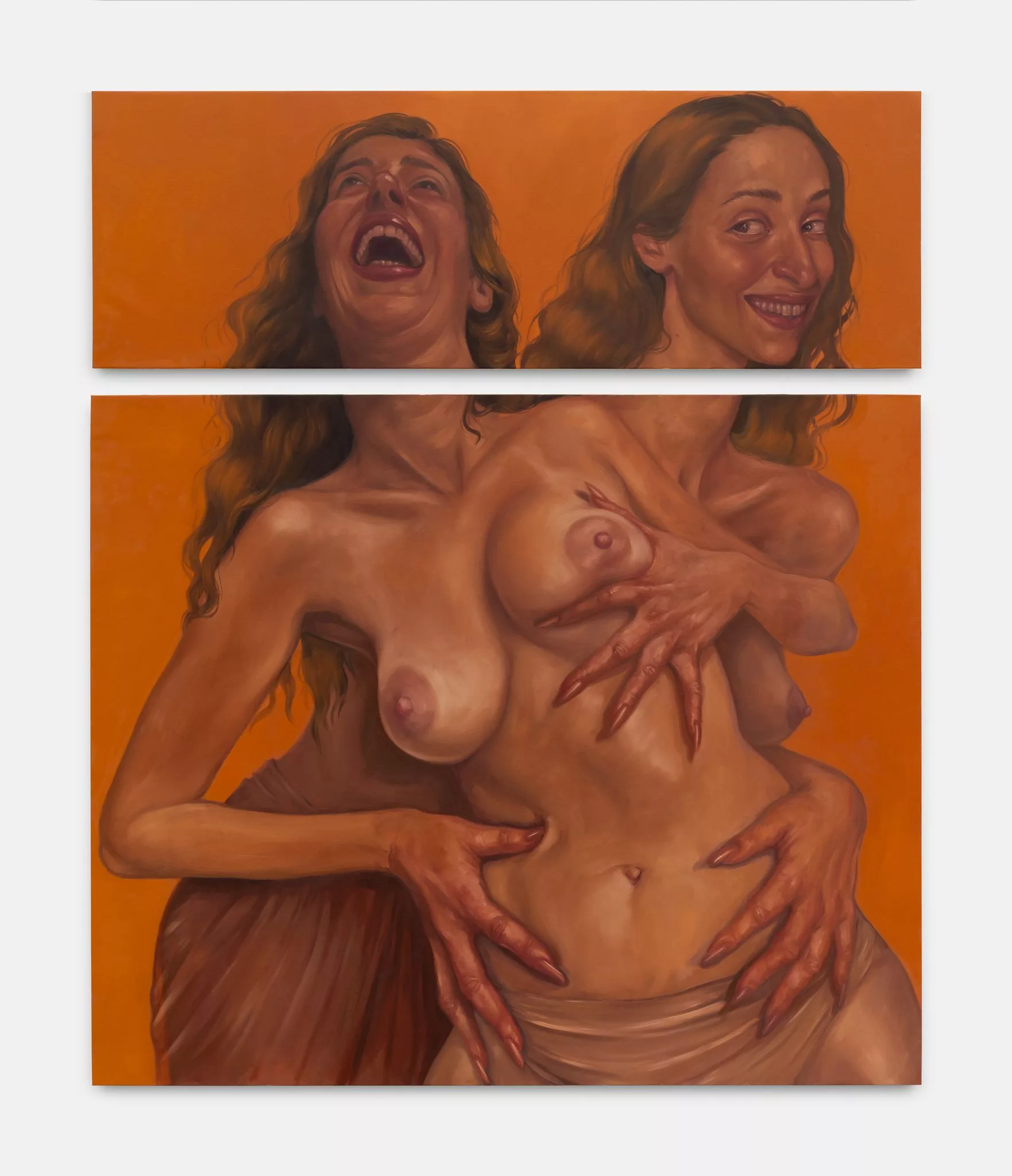

Where previous works by Wise have hummed with a low decibel of manic energy, the paintings in Torn Clean are throbbing with a mania so palpable that it threatens to shatter their contrived artifice. In one, the subject—a slim girl with an exposed breast and tangles of blonde hair—leans across the canvas, smiling from ear to ear. Despite her nudity, this is not a ‘come hither’ moment. Instead the girl seems to be purposefully distracting us from whatever is going on outside the frame. In another, a woman is reclining on a plastic sheet. Her face bears a contorted smile that suggests she’s masking a more primal instinct, her learnt facade of politeness isn’t concealing whatever is about to happen next, be it an orgasm, a scream, or a lunge at the viewer’s neck. Wise says, ‘We do this all the time, don’t we? We put on a big smile even when things are terrible, even when the world is ending. We try to conceal those primal instincts for as long as we can, but they’re always there under the surface threatening to make themselves known.’

Also included in this exhibition is a still life, but instead of a composed table with fruit we see the contents of the artist’s bag: an onion, lip balm, rubbish, plasters—a strange detritus of human life acknowledging the sticky, fibrous objects we rely on to maintain the homeostasis of our delicate human form. The sticking plaster is a recurring motif. Wise explains, ‘when we are cut, when we bleed, we have to acknowledge we are humans, that we are effectively soft sacks of blood that could spill open at any moment. But we don’t want to acknowledge that, so we put a plaster over a cut or we fake a smile.’ I tell her about the gory incident with the heels; ‘Ah! Now you need a bandage. How human of you!’

These bodily themes are central to Wise’s work, but there’s always an underpinning of something larger and more existential. These aren’t just paintings about the trials of performing femininity, they are about the horrors and ecstasies of being human. The evidence of Wise’s interest in philosophy and her investigations into what it means to be alive, if dying slowly, is enmeshed in every canvas. But there is also a sense that Wise knows what it means to not be human, that she is always contending with the other option—the grimace, the airbrushed, the alien.

In this first article for my new column, Reading Out Loud with Emily Burke, I talk with Wise about a book that I wasn’t expecting to have recommended to me by the artist: American Cosmic: UFOs, Religion, Technology by Diana Walsh Pasulka. I had predicted social theory, autofiction, philosophy, maybe—but aliens? The topic was a pleasant surprise.

It’s worth noting here that, much like her paintings threaten to, Wise is a proponent of ripping the Band-Aid clean off. This dialogue, which began as a discussion of her favourite book, quickly evolved into a conversation about life, death and the trajectory of our own souls. Put your tinfoil hats on kids.

EB: So, obviously, my first question is, do you believe in aliens?

CW: Are you crazy? Of course I believe in aliens! Do you?

EB: After reading this book, I’m getting there.

CW: Alright, okay, that’s the best news ever.

EB: But I think we have to define ‘alien’ first, right?

CW: Definitely. Because when you think of aliens you think of little green men, and it’s not that I don’t believe that’s possible, but we’re using human language and constructs to discuss things that may be outside our logical human framework and that by definition evade definition. So I guess, to answer your question seriously, I believe 1,000 percent that something exists that is totally alien to our limited understanding. And, let’s face it, to believe we’re alone in the universe is stupid. I think that the ‘phenomenon’ itself is a trickster and that is why this book is so great. It really explores this idea that the phenomenon can be something that we call by many different names. Divinity, for example.

EB: I liked that too. All of those historic religious encounters which through this lens could have actually been an interaction with the phenomenon.

CW: Exactly. Jacques Vallee, who Pasulka speaks about a lot, wrote a book called Passport to Magonia: From Folklore to Flying Saucers. He talks about these experiences people have with the phenomena, and if you believe in fairies, or ghosts, or God, that’s how you will encounter it. It will speak to you in a language you understand.

EB: Talking of synchronicities, how did you discover this book? Pasulka introduces this concept of the book encounter: the notion that the book finds you at just the right moment in time and guides you towards understanding UFOs.

CW: I’ve been really interested in the UFO phenomenon for a while now, and, obviously, I’m also interested in philosophy and psychology, so I read a lot of books that meet at the intersection of both. If you question the UFO phenomenon, you immediately get to questions of consciousness. Consciousness is something that neuroscientists haven’t pinpointed and so there’s a lot of burgeoning science that focuses on it. But, ultimately, it is philosophy, because it very quickly becomes a conversation about our souls, consciousness and divinity. I am also into the UFO phenomenon in a basic way, the nuts and bolts stuff, you know? Like the hearing that happened in the US Congress over the summer.

EB: Have you had an encounter with the phenomenon?

CW: I wish! I don’t know that I have ever had an experience, no. If you have, either you’re delusional or you’re incredibly lucky. Either way, I’m not judging it.

EB: What about other spiritual encounters?

CW: Bro … psychics. [laughs] Don’t look at me like that! I’m the first person to say that stuff is fake, but I’ve been seeing a psychic and she’s an angel. One day she woke up and had this Kundalini awakening, and now she has access to downloading. We got on Zoom and she started quoting something that she couldn’t have possibly known, quoting it word for word. I also have this weird thing where sometimes I just know when a Siamese cat is going to walk out in front of me.

EB: Okay. So the phenomenon is real and Chloe Wise is sitting outside staring up at the night sky wearing her tin hat …

CW: Yes, I have a really cute collection of tin hats actually!

EB: So why do you think that the aliens are so hesitant to introduce themselves?

CW: The example that I like to give is the idea of the body not recognising something foreign happening to it, even if it is for the best, like chemotherapy. Or think about what happens when I take a Tylenol. My body probably has no idea what is going on. From the outside, I know there is a reason I took the pill, but my body is confused by this strange new object impacting it. I think it is a bit like that. Maybe there are UFOs, or whatever, that surround the planet and come and make manifest in our lives occasionally. If you’re zoomed out, then you understand that it’s just washing its hair or taking a Tylenol. Or maybe it even has a sense of humour and it’s enjoying playing with us. But I think that we can’t even begin to understand the larger picture because we are just like the little gut bacteria inside of us that can’t make sense of probiotics.

EB: Or like how an ant would experience a human poking at its home with a stick. The ant wouldn’t even be cognisant of the term ‘stick’, let alone what was happening with it.

CW: Yes, exactly. And, actually, this idea relates to another book called Hyperobjects by Timothy Morton. He’s a total genius. It’s about the idea of the ‘hyperobject’, something like global warming or the environment. Something that is so big that we can’t point to one thing and name it as ‘the environment’. Because it is so complicated as an object, it becomes a hyperobject. It is viscous. There is no place where it stops and starts. So you end up bringing some of it with you when you have sand on your shoe or you ingest it. It’s entirely nontemporal. We might never see the whole cloud above us; we may only be able to see the shadow it casts. In a similar way, I like to think that the UFO phenomenon is a hyperobject. Maybe we’re all just coming into contact with these little moments of it and, as humans, we’re kind of humbled in the face of such a possibility.

EB: Like the encounter I just had with your painting! That vaguely nauseating feeling that something terrible is happening just outside the frame, which we only encounter through the model’s manic smile.

CW: Yes! This book, Hyperobjects, was hugely influential in my work for this show. Like you said about the smiling in my work, there’s a tension, there is a shadow above. Something terrible is happening outside the frame, something chaotic, violent, scary, morbid or simply anxiety inducing. Maybe it’s the reality of global warming and the reality of impending death, impending doom. Whatever it is, it’s too big to tackle. This is how we live our lives, right? Despite the knowledge of these unmanageable things, we walk around smiling and finding beauty where we can.

EB: There’s something noble about it. The brain has to filter certain things out in order to endure and survive.

CW: Yes. There are chaotic particles all around us. Right now I see a painting and a ladder in front of me, but really they’re just crazy, vibrating particles, and it’s my brain that is the interpreter.

EB: What did you make of the people who shared their UFO experiences in this book?

CW: I found their stories really moving, plus I’m kind of jealous! No, seriously, I think this is why this book is so meaningful. The author does such a brilliant job of being totally nonjudgemental, sharing these people’s stories which might otherwise be dismissed for being totally crazy. And then we, as the readers, get to consider not only what they believe, but what it means for mankind if what they believe is real.

EB: Yes, believing in belief for at least the duration of the book.

CW: Yes, a willingness to admit you don’t know everything, to open yourself up for a moment and listen to somebody else, to suspend your disbelief for a moment and to let their belief be enough. I think that’s really beautiful, what you just said about believing in belief. To me that’s the most profound possibility because it doesn’t suit the status quo under capitalism to consider any of this stuff. It doesn’t make us better citizens, or workers, or voters for us to look at the stars and take deep breaths and try to connect to ‘oneness’. Although I guess people do that these days, don’t they? Mostly in the hopes that it will make them better CEOs, but that is kind of incompatible with this type of searching. I have a tremendous amount of respect for anyone who has experienced any of this stuff, and, of course, for people like Pasulka, who bring an academic lens and some criticality to these studies. You need someone to take a multi-hyphenate approach to this stuff, because it’s not just phenomenology, it’s not just physics, it’s not just astronomy and astrology, or spirituality, or Christianity. It’s a much bigger, multi-pronged, huge, glimmering question mark—Are we alone here?

EB: Does all of this scare you?

CW: No. What’s truly scary is believing that everything is as we know it to be, according to science, and that everything we’re ever going to know is here in front of us. The first step to becoming an intelligent being is to admit that we don’t know anything. I’m scared of AI and I’m scared of technology, but I’m not scared of admitting that there’s some unknowable stuff out there. That’s what feels important to me, removing the stigma of all of this. But, then again, if it came out tomorrow that this was all invented by big tech, to stop us from realising we live in a simulation, I would be pissed that I had been an agent for them. Anyway, it’s just the idea that the truth is out there somewhere. I’m going to spend my whole life trying to contend with that.

Written by Emily Burke